The veterinary environment offers many challenges to a dog's capacity to remain relaxed (Shepherd, 2009). However, the majority of domestic dogs are faced with multiple stress inducing and welfare depleting encounters every day (Palestrini, 2009) so that for many dogs, the difficulties associated with the veterinary practice become the ‘last straw’ that leads to an already highly aroused dog becoming difficult to handle and potentially dangerous to the welfare of other patients, owners and staff (Bower, 2002). The role of the veterinary team in alleviating stress in the canine was the subject of discussion at The Veterinary Nurse workshops 2015 (Figure 1).

The dilemma

When a dog displays a behaviour — no matter how inconvenient for us — it is responding to environmental triggers and basing its behavioural decision on genetic/innate influences and the environmental opportunities that it has received for learning about what works to maintain its safety (Bowen and Heath, 2005). Although there is the capacity for considerable individual variation, as many dogs have failed to receive opportunities to learn to habituate to the wide range of social and physical stimuli around them, the influence of genetics should not be underestimated (Mills et al, 2013). Domestication may have created the capacity for cooperation with other species but it hasn't altered the dog's basic drive to succeed, to thrive and survive — nor has it altered the biologically adaptive methods of ensuring this: freeze, fiddle, flight or fight (Yin, 2009). Evolution has provided these natural responses to resolve social problems and the dog will automatically initiate them. Frustration or failure of these behaviours to resolve a problem will only invigorate efforts as the dog has no alternative tools to use (Mills et al, 2013).

All dogs need guidance in developing a socially acceptable behaviour repertoire (Dehasse, 2002). As veterinary professionals are the only specialists that are likely to see the family and puppy at 8 weeks when there is still time to resolve most potential problems, the veterinary profession is the main source of reliable information that the family is likely to access during the early part of developing their pet–owner relationship (Shepherd, 2009). Consequently, the emotional health of the developing dog should be as great a priority as their physical health. This is particularly the case as more dogs are euthanased annually as a result of incompatibilities between their behaviour and their families' expectations, than for any other reason and the majority of these dogs are under 3 years of age (Overall, 2013). This can lead to considerable financial loss to veterinary practices that could have expected to see that animal for routine veterinary treatments for approximately another 10 years.

Emotional arousal — the alternative to intervention

Failure of owners to assist their dog in habituation to a broad set of social and physical stimuli results in a dog that experiences frequent exposure to stimuli that induce emotional arousal owing to either:

- Anxiety: anticipation of a challenge or threat to the animal's perception of its safety, or

- Fear: learned and specific threat or challenge to an animal's perception of its safety. In addition to these, and often under recognised, is the likelihood of:

- Frustration: failure to get the expected reward or result following a behaviour (Mills et al, 2013).

Owing to the negative nature of this emotion, dogs learn to recognise stimuli that could result in a state of frustration, becoming increasingly anxious and fearful when presented with such stimuli.

Anxiety, fear and frustration all lead to increased arousal and whether the associated stress drives behaviours of approach or avoidance, increased arousal equates with management problems for owners and veterinary staff (Lindell, 2002).

Where does stress come into the equation?

No veterinary professional wishes to consider that their efforts to improve an animal's health are likely to concurrently impair its emotional welfare. Neither do they wish to consider that their actions may change an animal's perception of the social and physical world around it, increasing the chances of defensive aggression towards the social stimuli met in the environment outside the practice. However, as a result of the nature of many veterinary interventions, stress, associated learning and, consequently, an inability to remain true to professional oaths to do ‘none harm’ is almost inevitable (Roshier and McBride, 2012).

On occasion, our concerns regarding the negative aspects of stress cause us to forget that it is both natural and adaptive (Gray, 1987). Stress is a physiological response that enables an animal to react to changing circumstances. It can be either positive (driving behaviours that enable access to stimuli or resources that an animal desires), or negative (enabling an animal to distance itself from a stimulus). Stress allows the animal to react appropriately to the stressor and brings about the necessary response that will enhance the animal's physical and emotional welfare.

Consequently, we should accept that animals do get stressed and that stress in itself isn't the problem. The problem is whether the stress is:

- Acute: short term, efficiently driving behaviours that resolve the problem, or

- Chronic: ongoing when the selected behaviours fail to immediately resolve the problem and the animal's efforts to control exposure to the problem are frustrated (Mills et al, 2013).

Stress responses evolve to deal with acute (short-term) problems but domestic stressors are prolonged and may possibly continue for years. Without a coping mechanism, even mild stress, if prolonged, can be severely debilitating (Notari, 2009).

Coping and choice

To maintain an animal's welfare, the animal must have the ability to cope — the ability to manage its exposure to stressors (Mills et al, 2013). Coping involves behaviour that is intended to maximise survival. However, the selected behaviour isn't always consistent with the requirements of the owner or veterinary staff. The behaviour is simply intended to reduce the level of stress by avoiding exposure to negative stressors or gaining access to a positive stressor. It is the inability to control stress that creates poor welfare and, consequently, dogs need access to choices that enable them to avoid exposure to stressors. If we enhance the choices to include strategies to avoid negative stress (distress), welfare is maintained. If we improve the dog's access to effective choices that also enable owners and staff to maintain their safety, their welfare needs are also met. Consequently, by designing an environment and handling procedures that give the dog behavioural options to avoid stressors, we enable the animal to cope (Yin, 2009).

As a consequence of the above, animals need the ability to limit the impact of stressors on normal functioning and to retain competence when normal functioning is disturbed. They need to have the capacity to recover quickly following disturbance of functioning and to enhance future coping as a result of exposure to stressors (Mills et al, 2013). Coping doesn't occur through protection from stress, as then minor stressors become a major source of stress. Coping is created by exposing animals to stressors that are within their capacity to cope, enhancing future coping through gradually building up exposure to stressors that are likely to be faced in later life. This ensures that the animal has some control over its environment and level of exposure to the stressor. It is only then that a greater level of exploration can occur and further coping strategies develop.

How do we know when a dog is stressed?

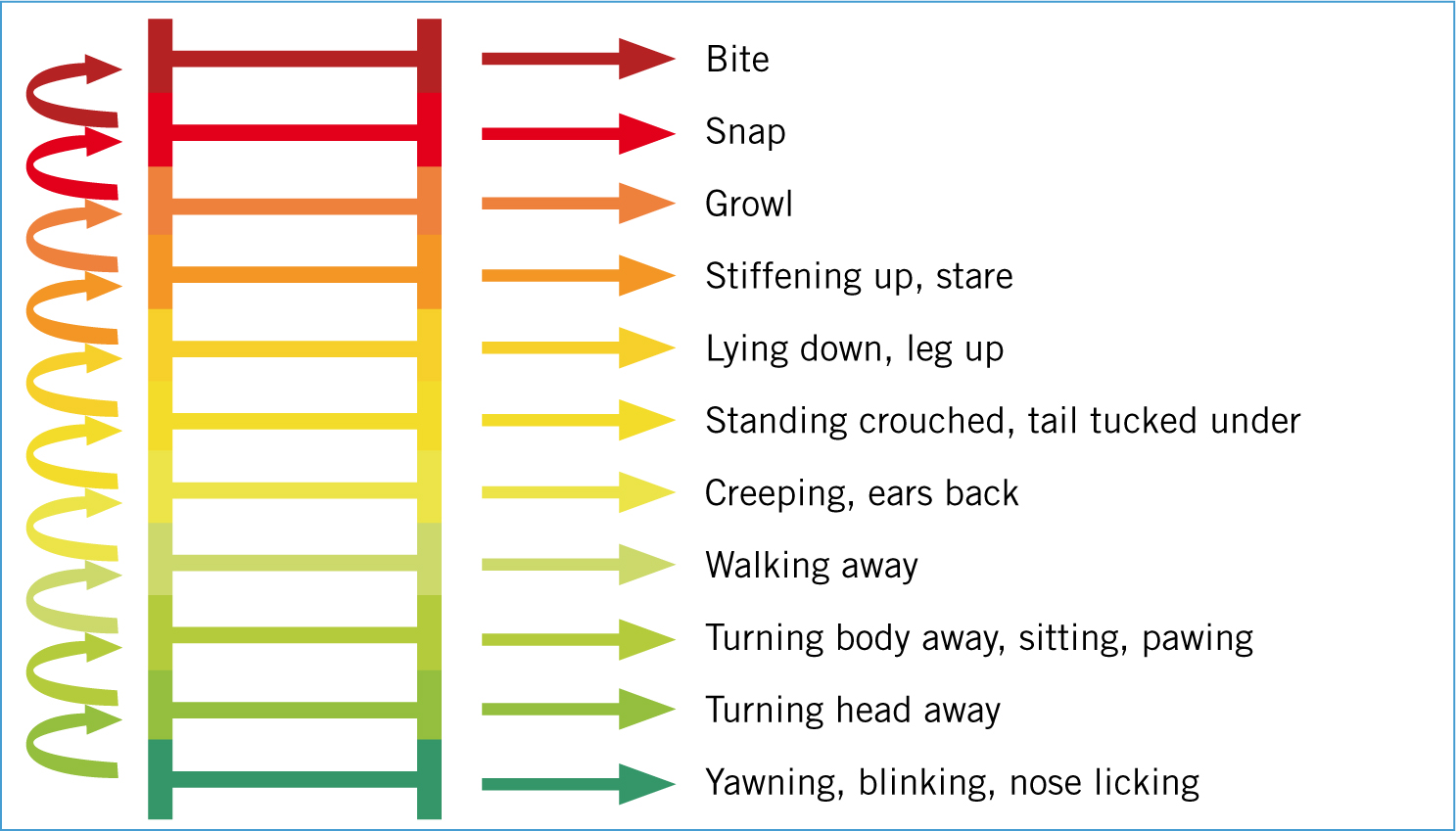

To provide appropriate behavioural options for dogs, we must first be able to recognise the stressed dog by learning to read what it's telling you. Both the first and second editions of the BSAVA Behaviour Handbook give veterinary staff access to Kendal Shepherd's ‘Canine Ladder of Aggression’ which gives helpful tips on behaviours to note (Shepherd, 2002; 2009). It also notes how failure to respond in a manner that enables the dog to perceive a reduced exposure to stressors will potentially lead to the dog engaging in defensive aggression (Shepherd, 2002) (Figure 2).

Preparation and safety

Our environment is constantly changing and, consequently, change is unavoidable. Although some dogs seem genetically robust and cope better than others, without the flexibility to accommodate to a changing environment, an animal is forced to live a life of depleted welfare (Landsberg et al, 2013).

Stress involves metabolic or physiological changes, alterations in the nervous and/or endocrine systems which may be sufficient to resolve the problem, particularly if the stressor is internal. However, external stressors are likely to require behavioural change followed by psychological (cognitive) change creating learning that will enhance the effectiveness of the animal's strategies on future exposure (Mills et al, 2013). All of these responses are intended to maintain the animal's body at an optimal working state and an animal may have to work hard to restore this state — especially if its efforts are frustrated.

Owners expect pets to be confident when outside the home. However, this can be impossible if relationships at home are unstable or unpredictable, as the dog will need to focus too much attention on relationships and will be unable to widen its concept of habituation to the environment outside, possibly becoming more sensitive to it. A sense of safety is an important priority for any animal (Maslow, 1943) as it needs to know that it can escape harm — it needs to know that it can choose to withdraw from situations of threat or potential conflict. When a sense of safety is absent, a dog can't be expected to expend energy on creating good social relationships with strangers as its priorities lie with maintaining safety and coping.

Stress chemistry

In addition to the well-understood chemical effects of stress, are a few that we rarely consider (Figure 3). In addition to the expected physiological changes, cortisol also alters learning, biasing an animal's attention to negative events and sensitising it to previously neutral stimuli (Notari, 2009). Prolonged exposure to cortisol, as occurs in a chronically or frequently stressed animal or in an animal on long-term corticosteroid treatment, is toxic to areas of the brain (including the hippocampus) involved in learning, leading to the potential for dishabituation and sensitisation. During stress-induced dishabituation, previously habituated stimuli become significant and as a result of cortisol suppressing the immune system of chronically stressed animals, veterinary staff are more likely to see recurring infections across systems (Notari, 2009).

The raised prolactin levels of stressed dogs result in reduced dopamine activity. Dopamine enhances goal-seeking behaviour and reduced levels of the neurochemical result in a decrease of behavioural activation and increase in depression (Mills et al, 2013) — a possible explanation for the many seemingly ‘compliant’ canine patients that are actually experiencing behavioural inhibition and possibly learned helplessness. In addition, the oxytocin released during the stress response may increase the dog's need for its secure social base, enhancing the likelihood of separation problems, particularly in hospitalised dogs (Mills et al, 2013).

Domestic stressors and their relevance to the veterinary environment

Most stressors in domestic life are met frequently; many so frequently that the dog has insufficient time to recover from previous exposure (Neilson, 2002). As the neurochemicals associated with stress take many hours (and sometimes days) to degrade, from the point of view of exposure to stress-related chemicals, this effectively means that the frequently stressed dog is little different to the chronically stressed animal. We can expect such dogs to display hypervigilance, hyperactivity, irritability and recurrent anxious conflict behaviour (Mills et al, 2013). Such dogs may look well-adjusted in the veterinary consulting room but remain highly physiologically aroused. In addition, those dogs exposed to chronically enduring stressors will have a higher metabolic rate, enhancing physiological problems including the acceleration of age-related physical and cognitive changes (Notari, 2009).

Owing to the cumulative nature of stress-related biochemistry and the regularity with which domestic dogs face stressors in their daily lives, it is inevitable that the dog entering the veterinary surgery does not do so from a position of emotional neutrality. Consequently, any stressors, even minor ones, are likely to have a significant effect on its behaviour. When the dog's attempts to cope are thwarted by the necessity for staff to continue examinations and treatment, it leaves the dog with very limited choices. It can continue with the original response, but more excessively. If this fails to bring about a resolution to the problem of a perception of threat to its safety, the resulting frustration leads to increased irritability and defensive aggression (Notari, 2009). The animal may attempt to find an alternative strategy, e.g. shifting from an unsuccessful attempt at flight to fight. The dog may also give up, entering behavioural and emotional depression — a state of learned helplessness, when the animal learns it has no control over its environment (Mills et al, 2013). However, within the veterinary environment, all of these strategies will lead to a failure of the dog to succeed and, therefore, will result in enhanced frustration.

Consequently, staff are likely to encounter emotional and behavioural changes linked to frustration such as:

- Ambivalent behaviour: the dog may try to display different behaviours, e.g. approach-avoidance conflict behaviours. Any failure of staff to respond clearly can escalate this problem and result in aggression

- Displacement behaviour: the dog may try distraction techniques such as scratching (seen as irrelevant to humans). The dog is experiencing emotional conflict and may struggle to adopt an appropriate response; it plays for time until an appropriate response becomes more obvious

- Redirected behaviours: the dog displays behaviour that it has had success with previously, and is directed onto an alternative target, e.g. aggression (Mills et al, 2013).

Subsequently, some dogs will take the initiative when frustrated, becoming increasingly aroused, while others are more passive, becoming withdrawn. However, any of these styles indicate a welfare problem and failure of veterinary staff to intercede appropriately guarantees more persistent and excessive expression of the selected behaviour. Time may also cause generalisation into other circumstances, including the home and physical environment outside the practice.

Why is the veterinary practice such a stressor?

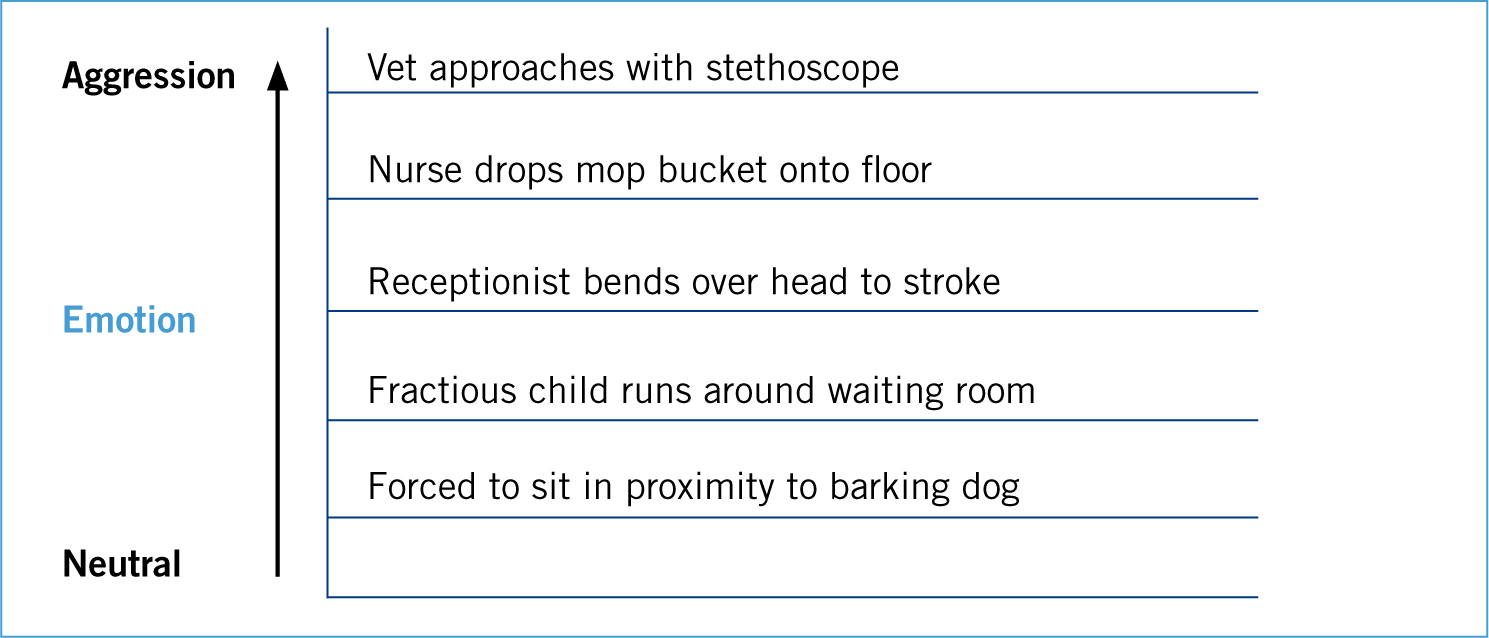

Many dogs will struggle to cope with the journey to the practice; small dogs may travel in a carrier to which they are sensitised, many dogs will have various levels of travel sickness and others will be classically conditioned to initiate fear or anxiety on recognising stimuli that predict their destination (Neilson, 2002). Even for those dogs that readily travel to the practice car park, the alarm pheromones that they may detect in the waiting room will assail their vomeronasal organ on entering the waiting room and will initiate stress. Then there is the inevitable exposure to novel noises, smells (e.g. disinfectants and staff perfumes), social stimuli — both human and canine — and emotional arousal when placed in proximity to cats and small mammals (Palestrini, 2009). All of these lower the dog's ‘threshold for aggression’ (Figure 4).

Aggression threshold is severely reduced by emotionally arousing events experienced throughout the day, and from day to day, dependent on what has preceded an incident.

How can we change this?

By its very nature, the veterinary practice provides experiences that are novel or not routine, or there is an association of discomfort or pain, that will invoke a negative emotional response in the dog (Roshier and McBride, 2012). Consequently, there is a professional responsibility to recognise stress and to respond in a manner that reduces the level of threat experienced by the dog, thereby enabling coping (Shepherd, 2009).

As the pet may start to feel stressed on the journey to the practice owners can ensure:

- The pet is safe and secure within the car through the use of a crate or harness

- A considerate driving style

- Good ventilation

- Once at the vets, consider waiting in the car until you are called to minimise the wait time indoors.

In addition, there is a responsibility to:

- Minimise environmental pheromonal messages of potential threat and conflict through use of Adaptil (Ceva Animal Health) which is a synthetic copy of the dog appeasing pheromone, to provide environmental messaging associated with familiarity and security

- Minimise the dog's experience of stressors in all veterinary environments, starting with the prevention of unwanted social encounters in the waiting room through imaginative use of temporary barriers and removal of distressed dogs from the building until their clinician is ready to see them

- Teach staff, owners and dogs how to enhance coping through staff and owner's provision of constant guidance to the dog and reinforcement of cooperation

- Use handling techniques that maximise the dog's perception of choice and minimise restraint

- Use sufficient analgesia to ensure the dog's comfort and limit its experience of stress and the need to prevent access to its body

- Use sufficient sedation and anaesthesia to ensure that veterinary examinations occur without the dog failing to cope resulting in learned negative associations

- Use short-term memory-blocking agents, when a negative experience has become unavoidable, to prevent learning impeding future veterinary visits or altering the dog's general perception of interactions with humans.

If intensive intervention is to be avoided, dogs must encounter an environment where there is time to teach them how to respond appropriately (Serpell and Jagoe, 1995), right from their first visit to the practice (Shepherd, 2009). Pre-vaccination visits should inform new puppy owners of the importance of socialisation and environmental referencing, as well as how to achieve this through habituation rather than accidentally sensitising the puppy. In addition, owners should be shown how to teach their puppy to ‘look at me’, ‘sit’, ‘lie’, ‘stand’ and ‘roll-over’ through the use of food lures and visual signalling. This offers the veterinary team the opportunity to work ‘hands-off’ regarding restraint, on an animal that expects them to give it guidance and reinforcement for cooperation (Yin, 2009).

Staff should also avoid giving a perception of conflict through the dog misinterpreting their body language, aiming to avoid staring and leaning over animals (moving from side to side of the dog or working from behind it when, e.g. auscultation is required); observing the dog's communication throughout (Yin, 2009). If patients don't enter the consulting room willingly, try to leave a door open or rearrange the consultation to occur in the waiting room (perhaps just before the surgery's opening time) or consider whether the dog would cope better if examined in an exercise yard or car park.

Hospitalisation will inevitably increase the likelihood of stress associated with fear, anxiety, frustration and learned helplessness. Procedures such as blood tests, catheterisation, dressing changes and fluid therapy will all initiate arousal and a perception of threat and, consequently, extra care should be taken to maximise a concept of choice and coping within this environment.

Pheromones and pheromonotherapy

The canine patient will encounter alarm pheromones and experience stress initiating arousal within seconds of entering the veterinary practice. Therefore, all canine patients will benefit from the proximity of dog appeasines in the form of pheromonotherapy using Adaptil (Hargrave, 2014).

Pheromonotherapy is the use of synthetic analogues of pheromones derived from natural bodily secretions to modify the behaviour, altering the dog's perception of the environment by stimulating brain circuits associated with recognition and familiarity. This response is unconscious and removes the need for general behavioural suppression that might previously have been required to bring about a change in behavioural response. As the vomeronasal organ receptors are directly linked to the limbic system of the brain, the pheromones can rapidly moderate emotional behaviour without necessarily invoking any conscious awareness, evoking normal circuits associated with feelings of recognition and familiarity (Mills, 2002).

The advantages of using pheromones are numerous; pheromones are messengers (they are not absorbed into the animal's bloodstream and, consequently, there is no toxicity or side effects), there are no interactions with any medication (even psychotropic drugs), and can be used with old or ill animals (Mills, 2002). As a result, the use of Adaptil in the waiting, consulting and ward areas can only assist in reducing stress and arousal in canine patients (Mills et al, 2006).

Conclusion

Failure to prepare adequately for the complexity of the human world, including veterinary visits, can have a devastating effect on a dog's welfare. The active responders to stress are hard for owners to ignore, leading to treatment, relinquishment or euthanasia—the alternative being a life of chronic stress and severely depleted welfare. However, the passive responders to stress are rarely noticed by owners or veterinary staff and continue to suffer.

The professional guidelines that enshrine the need for veterinary staff to ensure both the physical and emotional welfare of their patients are inadvertently flouted on a daily basis. This need applies both within the practice and, due to the associated negative learning about the physical and social challenges in the veterinary environment, permanent changes in the dog's relationship with other environments can also be created. Veterinary nurses have the power to change this!

Main Worksop Learning Outcomes

- It is inevitable that dogs will experience stress in the veterinary practice.

- Stress-related behaviours are likely to be owing to anxiety, fear, frustration or learned helplessness.

- Failure to reduce stress and enhance coping in dogs will frequently result in aggression.

- Learning associated with experiences in the practice may generalise to the home environment.

- Preventive advice and early intervention can enhance canine coping and staff/owner safety.

- Pheromonotherapy can reduce canine-arousal behaviours by creating a perception of familiarity and security.