Corneal ulceration is one of the most common ocular disorders presented in first opinion practice (Startup, 1984; O'Neill et al, 2017). Corneal ulceration is described as a break in continuity of the corneal epithelium with exposure of the underlying stroma; they can be classified according to depth and extent (Maggs, 2013). Anecdotally, registered veterinary nurses (RVN) are often underutilised in veterinary practice and the author has noticed a particular underutilisation in ophthalmic nursing in first opinion practice (Gerrard, 2017; Harvey and Cameron, 2019). RVNs can be well utilised in corneal ulceration cases — their role extends from the recognition and understanding of corneal ulcers, ensuring appropriate handling and restraint, performing routine ophthalmic tests, recognising ophthalmic pain and supporting and educating owners.

The first part of this two-part series looks at the aetiology of superficial corneal ulcers and spontaneous chronic corneal epithelial defects (SCCED), the associated complications and the medical and surgical treatment options. The second part will discuss the aetiology, diagnosis and treatment of deep corneal ulcers and descemetoceles, and will explore the role of veterinary nurses in ophthalmology including: routine ophthalmic tests, patient handling and client education.

Anatomy of the cornea

The cornea is the clear, avascular anterior portion of the coating of the globe, which is composed of four basic layers: the epithelium; the stroma; the Descemet's membrane; and the endothelium (Turner, 2008; Sanchez, 2014). The corneal thickness is approximately 0.45–0.55 mm (Turner, 2008). The epithelium comprises a multicellular layer, containing non-keratinised stratified squamous epithelial cells, which attach to the underlying stroma. The stroma is a collagen rich extracellular matrix composed of keratocytes and proteoglycans assembled to provided strength, transparency and hydration (Chen et al, 2015). The inner most layer, the endothelium with the Descemet's membrane, contains a single layer of cells which aid dehydration of the cornea. There are various factors that can influence the process of corneal healing and each corneal layer responds to injury in a different way, therefore, determining what type of ulcer a patient has is vital for optimal treatment.

Superficial ulceration

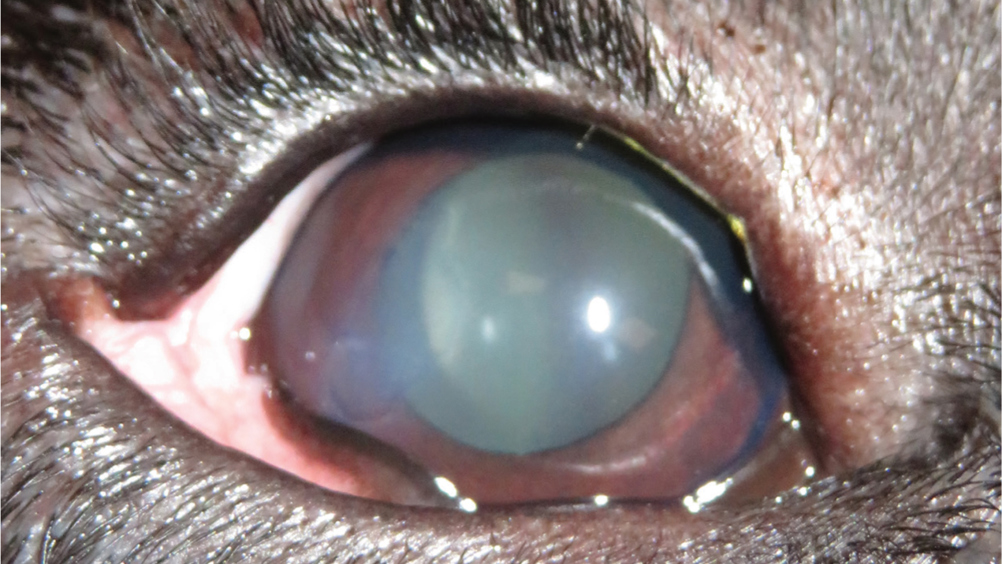

Corneal ulcers affecting only the epithelium are classified as superficial ulcers, they involve the loss of the epithelial layer and are at risk of secondary bacterial infection (Figure 1). Generally, uncomplicated superficial ulcers should heal with treatment within 7 – 10 days, as the corneal epithelium divides to re-establish epithelial thickness and the cornea should heal without associated fibrosis. Superficial ulcers can occur for a variety of reasons but they are often traumatic in nature (stick injury, cat scratch); other causes include an underlying ophthalmic disease.

Treatment of superficial ulcers should include a topical broad-spectrum antibiotic as secondary bacterial infection by the residential flora can cause further deterioration. The adnexa and orbit of the canine and feline eye are heavily innervated with sensory neurons, and ophthalmic disease is thought to cause moderate to severe pain (Mathews et al, 2014). Superficial ulcers in particular can cause considerable pain, therefore, the application of a mydriatic agent to relieve painful ciliary muscle spasm should be considered if reflex uveitis is present. Reflex uveitis often presents with signs of miosis, decreased intraocular pressure (IOP) and aqueous flare (Allbaugh, 2019). The use of a systemic non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug or opioid can also be implemented if indicated.

There are numerous factors that can result in the corneal-healing process not progressing as expected following routine treatment. On initial presentation, a full ophthalmic examination should be performed to determine underlying or contributing causes, which could prevent healing. If the superficial ulcer is not determined as traumatic in nature, there will often be an underlying cause such as entropion, distichiasis, or keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS ‘dry eye’). These conditions often lead to corneal irritation, exposure or corneal oedema which can prevent corneal healing and lead to further ocular defects, therefore, diagnosis and treatment of the underlying cause is essential (Table 1). If no underlying or contributing factors can be identified, a non-healing ulcer should be considered.

Table 1. Causes of corneal ulcers

| Cause of corneal ulcer | Description |

|---|---|

| Tear film deficiencies | Inadequate corneal protection due to keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS) can lead to corneal ulceration |

| Eyelid malformation/dysfunction | Eyelid malformation and dysfunction can lead to exposure of the cornea and corneal ulceration. Examples include: lagophthalmos, macropalpebral fissure, cranial nerve (CN) VII and CN V paralysis, ectropion |

| Endogenous cause | Endogenous causes of ulcers often include mechanical abrasion due to: entropion, distichiasis, ectopic cilia, trichiasis, eyelid masses |

| Exogenous cause | Exogenous causes include trauma such as cat scratch injuries or foreign bodies |

Spontaneous chronic corneal epithelium defects

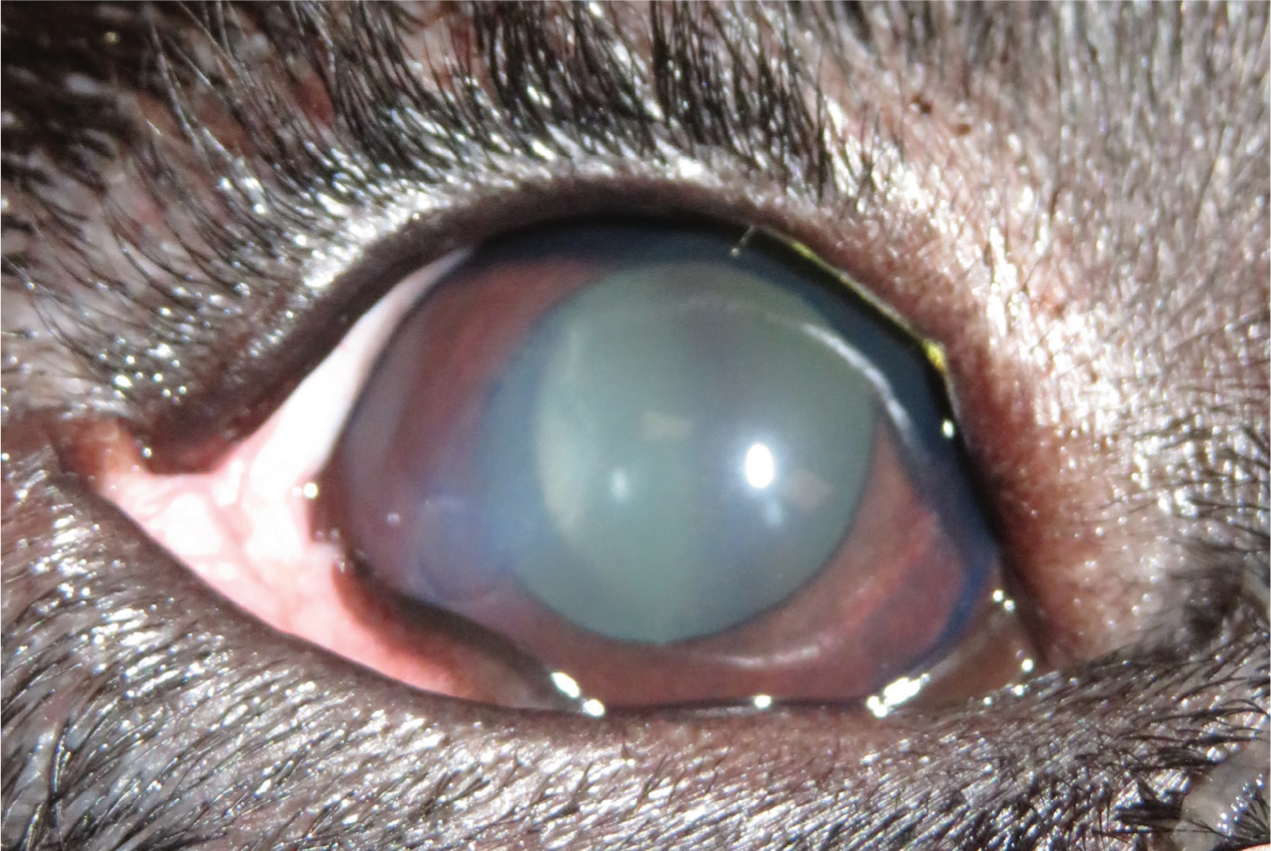

Spontaneous chronic corneal epithelial defects (SCCEDs), also referred to as ‘boxer ulcers’ or ‘indolent ulcers’, typically present with the loss of corneal epithelial basement membrane and the formation of a superficial hyalinised area in the stroma (Bentley, 2005). SCCEDs are characterised by a chronic superficial ulceration that fails to resolve, their management is particularly important as they are painful, can affect vision and often persist if left untreated. A failure of attachment exists between the basal epithelium to the basement membrane and stroma, resulting in a loose flap of epithelium under which fluorescein will be retained (Figure 2). Esson (2015) described that SCCEDs will often present with a visible rim of poorly adherent epithelial tissue which is easily under-run by fluorescein dye, appearing as a ‘halo’ of corneal staining. SCCEDs typically present in middle-aged dogs of all breeds, however, they are particularly common in large breed dogs including boxers, Staffordshire Bull Terriers and Golden Retrievers (Murphy et al, 2001; Hung et al, 2020). SCCEDs may be present for weeks to months, especially without appropriate management and are often painful and can affect vision.

Treatment of spontaneous chronic corneal epithelium defects

SCCEDs are often treated by physical debridement of both loose superficial epithelial tissue and the underlying surface, medical therapy alone is unlikely to result in corneal healing as they do not address the underlying morphological and functional corneal aetiological abnormalities that prevent the normal healing (Gomez, 2018). The client should be advised before any treatment, that the healing process can be challenging and recurrence is possible in the contralateral eye within 24 months (Hung et al, 2020). The recurrence rate of the same eye is less predictable but still possible, dependent on the type and success rate of the procedure that has been performed. There are several different treatment methods for SCCEDs, the most common procedure to encourage healing is debridement of the corneal defect in conjunction with a keratotomy.

There are various treatment options available including:

- Epithelium debridement (with a cotton bud)

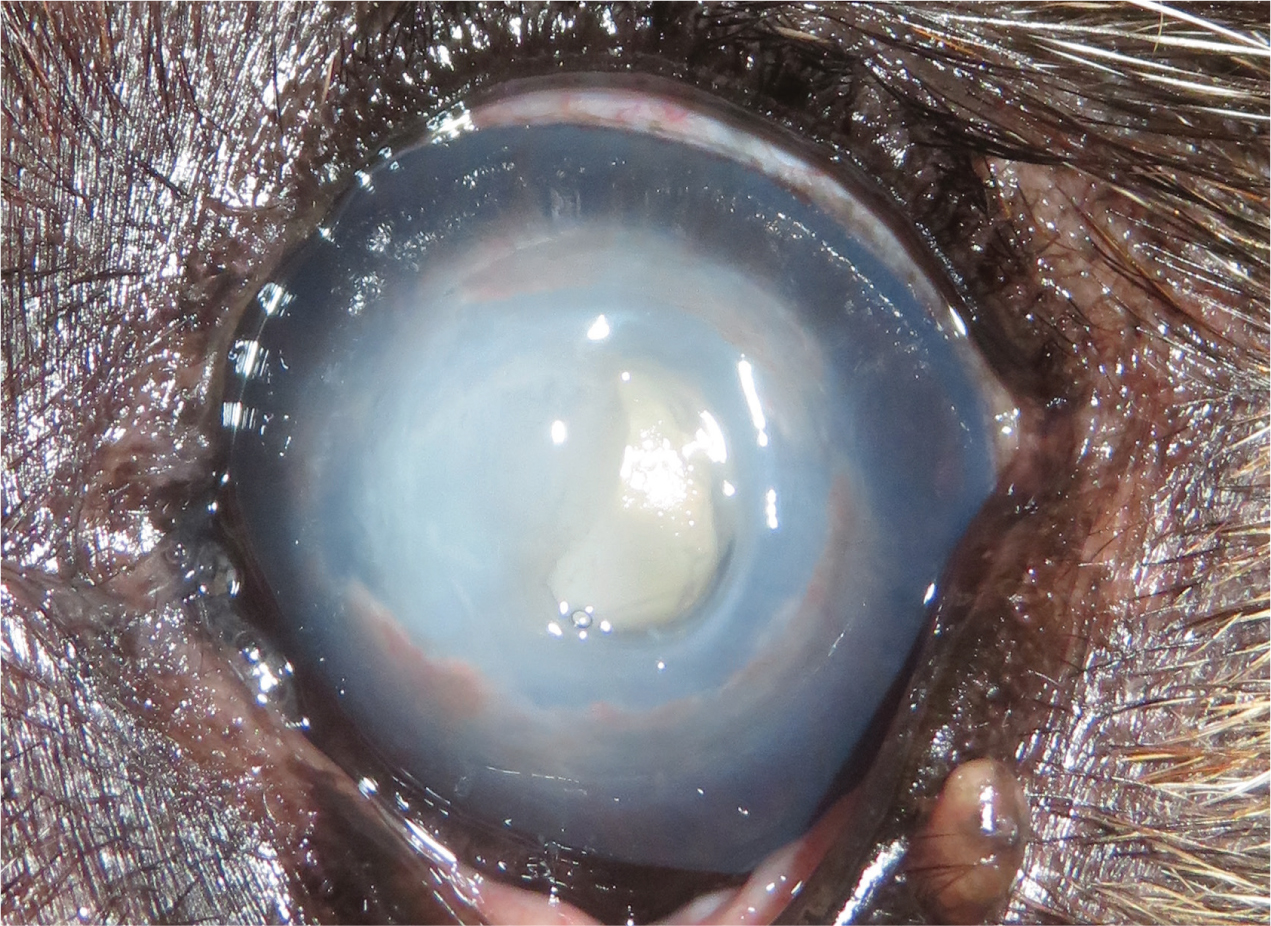

- Diamond burr keratotomy (Figure 3)

- Punctate or grid keratotomy

- Thermal or chemical cautery (with phenol).

Epithelial debridement

Each of these methods have variable success rates and preference differs between veterinary surgeons, however, all methods of physical debridement will aid healing (Bentley, 2005). Epithelial debridement is the removal of non-functioning, non-adherent tissue; the loose epithelium can be gently rubbed off with a sterile cotton bud or ophthalmic spears. This procedure can be repeated every 14 days (Bentley, 2005), however, to encourage healing debridement is usually combined with a superficial keratotomy, as debridement alone is unlikely to encourage renewal of epithelial adhesions (Wu et al, 2018).

Diamond burr keratotomy

Superficial corneal debridement with a diamond burr (Figure 3) is usually favoured because of its high success rate of 92.5% and it is usually well tolerated under local anaesthesia (Sila et al, 2009; Gosling et al, 2013). Diamond burr debridement significantly reduces the superficial hyalinised area in the stroma, and a reduction of this thickness may be responsible for the healing rates that have been reported in several studies (Gosling et al, 2013; Dawson et al, 2017). Diamond burr debridement is also becoming the favoured option as more traditional treatment methods, such as grid keratotomy, often result in more scarring.

Punctate/grid keratotomy

Several studies have shown that both punctate/grid keratotomies and diamond burr debridements are effective treatment options for SCCEDs (Spertus et al, 2017; Wu et al, 2018). Punctate keratotomy is the use of a needle held perpendicular to the cornea, to repeatedly ‘tap’ the ulcerated area to penetrate the anterior stroma. Grid keratotomy differs slightly to this as the needle is used to create several parallel horizontal and vertical lines in a grid pattern. Patients undergoing these procedures will often need sedation or general anaesthesia, as minor head movement would be detrimental to the eye; topical anaesthesia can be applied to the sedated patient to desensitise the cornea and aid the procedure (Abrams, 2008).

Thermal or phenol chemical cautery

Thermal or phenol chemical cautery is generally less favourable, as Williams (2014) stated that inappropriate use can cause further ocular damage, and could make future surgery such as superficial keratectomy less successful. However, some surgeons may choose thermal or chemical cautery as an alternative to procedures such as superficial keratectomy (Bentley and Murphy, 2004).

Complications of treatment

The treatment options can result in complications including excessive granulation, vascularisation, and scarring and pigmentation following corneal healing. Formation of excessive granulation and vascularisation is often a result of repeated debridement. Debridement and keratotomy can be repeated depending on the progress of the healing ulcer, but ideally 10–14 days should be left between treatments to allow the cornea to heal and reduce the likelihood of scarring and pigmentation (Jaksz and Busse, 2017).

An important complication to consider with any of the keratotomies is keratomalacia or ‘corneal melt’. Keratomalacia is caused by the release of endogenous and exogenous collagenolytic matrix metalloproteinase enzymes; an imbalance of these proteolytic enzymes and proteinase inhibitors in the cornea, and often the presence of microbial infection, leads to an unstable cornea that has a high risk of corneal perforation (Ollivier et al, 2007). Intensive medical therapy has the potential to achieve healing of some ulcers with keratomalacia, although surgical stabilisation is often required because of stromal loss (Guyonnet et al, 2020). Medical management alongside surgical procedures is recommended to reduce the risk of keratomalacia and uveitis (Gomez, 2018).

Although, keratomalacia is a rare complication following diamond burr debridement, the build-up of contaminants has been reported in studies to be a contributing factor (Spertus et al, 2017; Banks et al, 2019; Figure 4). RVNs should aim to maintain debridement equipment and sterilisation of diamond burr tips is highly advisable (Spertus et al, 2017). Manufacturer-recommended cleaning protocols should be followed, Eickemeyer Veterinary Equipment recommend cleaning the burr tip as soon after use as possible, as a delay in sterilisation will allow contaminants to dry and make cleaning more difficult. Eickemeyer Veterinary Equipment also recommend using an ultrasonic cleaner followed by sterilisation with a pre-vacuum autoclave cycle; the instrument should be visualised before this to determine its wear level and any damage. Spertus et al (2017) followed manufacturer guidelines and found that there was no diamond particle damage after 10, 25 or 50 uses, cleaning and sterilisation periods, suggesting that re-using the diamond burr tip is acceptable. However, secondary electron imaging found that repeated uses resulted in a build-up of carbon, sulphur and calcium on the burr tips, suggesting that over-use could be a contributing factor to delayed healing. A later study by Banks et al (2019) used two cleaning methods: group 1 with a dry steriliser and group 2 with ultrasonic cleaning and pre-vacuum autoclave. Group 1 results showed that there was no significant damage to the diamond burr tips after 100 cycles, however, particulate matter was not removed adequately, discouraging this cleaning method. Group 2 results showed adequate particulate matter removal and sterilisation, however, greater damage occured which indicated that the diamond burr tips should be replaced regularly when showing signs of wear or after 100 cycles. Moreover, for cases where keratomalacia is a concern, single use of diamond burrs could be considered.

Superficial keratectomy

For SCCEDs that are refractory to the above procedures, a superficial keratectomy can be considered, this technique is highly effective, with healing rates of 97.6% and 100% being reported in several studies (Stanley et al, 1998; Bayley et al, 2019). Superficial keratectomy involves the removal of the superficial corneal stroma and the hyaline membrane to allow the regeneration of epithelial adhesions. It is an invasive procedure for the cornea and can result in reduced corneal thickness and potentially more scarring and pigmentation than debridement and keratotomy. Superficial keratectomies require a general anaesthetic, an operating microscope and microsurgical instrumentation, therefore, previous debridement options described should be considered first and referral to an ophthalmic specialist is highly recommended for difficult cases.

Medical treatment plans

Following either a keratotomy or keratectomy, a medical treatment plan should be implemented to aid the healing process. Topical treatment should include a topical antibiotic, topical lubricants and systemic anti-inflammatories and/or analgesia. Ideally, topical and systemic antibiotics should be determined by corneal culture and sensitivity (Ollivier, 2003), however, broad-spectrum antibiotics can be initialised before the availability of results (Hindley et al, 2016). Collagenase inhibitors should be considered in cases of keratomalacia to counteract the effect of the proteolytic enzymes; autologous serum is commonly used for its anti-collagenase properties and immunoglobulins (Bhardwaj 2016; Guyonnet et al, 2020). Some studies have shown that combining several protease inhibitors may be beneficial (Ollivier, 2003; Guyonnet et al 2020) and oral doxycycline has been reported to modify corneal inflammation and have a positive effect on corneal healing (Pot et al, 2014). Veterinary surgeons should follow the BSAVA ‘PROTECT ME’ principles when prescribing antibiotics and consider if the use of doxycycline as a protease inhibitor is the best course of action. A bandage contact lens can be applied to provide mechanical protection, Grinniger et al (2015) suggested that the placement bandage contact lenses following the debridement of SCCEDs can improve comfort and potentially reduce healing time. The patient should be routinely examined and re-examination of the patient is often determined on the type of ulcer and risk of keratomalacia.

Conclusion

Corneal ulceration is a common ocular problem presented in first opinion practice; with a variety of aetiologies and differences in management, it is vital that veterinary professionals have a thorough understanding of the presentation of corneal ulcers. The second part of this two-part series will discuss deep corneal ulcers including descemetoceles and explore the role of registered veterinary nurses in ophthalmic cases.

KEY POINTS

- Corneal ulceration is one of the most common ocular problems, knowledge of the types of ulcers and the disease processes involved is key for appropriate management and holistic nursing care.

- Spontaneous chronic corneal epithelial defects are characterised by failure to resolve and often persist if left untreated.

- The identification of corneal ulcerations is key as they have different management strategies and can often be difficult to control.