References

Improving utilisation of RVNs in dermatology cases

Abstract

Pressure on veterinary surgeons to prescribe antibiotics can present in many formats, these can include, time, financial and the owner's expectations. Protocols and guidelines set out within the veterinary practice can help veterinary surgeons by providing structures on how to proceed in set circumstances. Veterinary bodies and representative associations have produced literature and guidance notes on antimicrobial use and these can be built into veterinary practice protocols and clinical guidelines. The introduction of an ear cytology microscopic examination being performed prior to antimicrobial prescribing showed an increase in the utilisation of the registered veterinary nurse (RVN) in the performing of this task, and a decrease in the net value of topical antimicrobials being prescribed was noted. The overall financial value to the practice was however increased.

Responsible use of antimicrobials has been widely discussed in all forms of the media, not just the veterinary press. Veterinary bodies and representative associations have all shown support towards reducing the overall amount of antimicrobials that are prescribed and used with the veterinary field (Ungemach et al, 2006). Actively reducing the usage of antimicrobials in veterinary practice has been suggested with the encouragement of laboratory analysis of samples for culture and selectivity prior to antimicrobial prescription, alongside education of prescribers on the importance of antimicrobial resistance (Hardefeldt et al, 2018). The results of culture and sensitivity laboratory tests can however take time and have a financial implication. Pressures from pet owners on veterinary surgeons for results and sometimes for the actual medications can make this difficult.

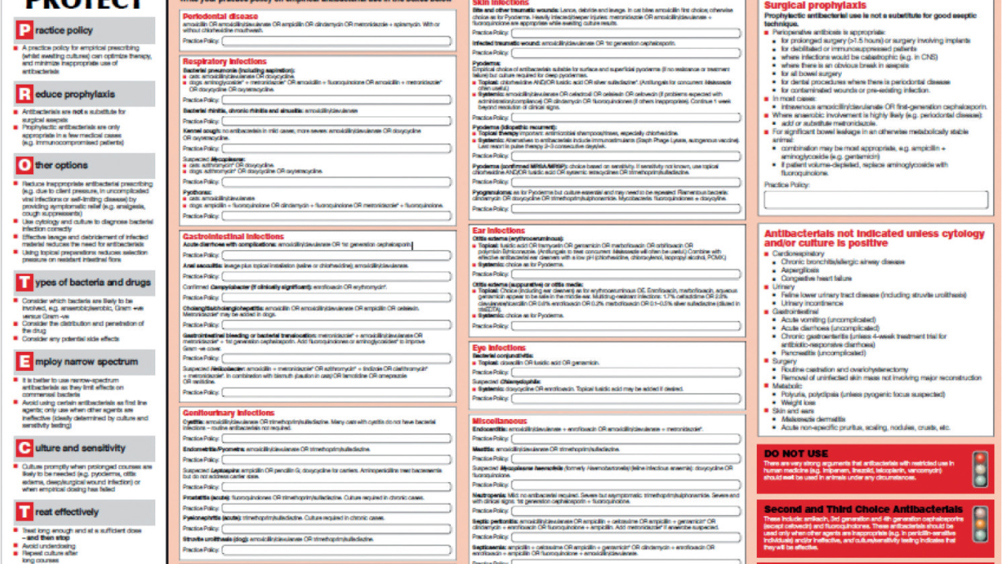

Veterinary practices may stock a number of different ear preparations and cleaners based on first- and second-line preferences, which may be set out by a practice protocol or guidelines. In many practices, within the UK, this is in line with the British Small Animal Veterinary Association (BSAVA) PROTECT recommendations. The Association set out recommendations for antimicrobial use in specific circumstances based on cytology (BSAVA, 2014), (Figure 1).

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting The Veterinary Nurse and reading some of our peer-reviewed content for veterinary professionals. To continue reading this article, please register today.