References

Looking after the end-of-life patient: four case studies

Abstract

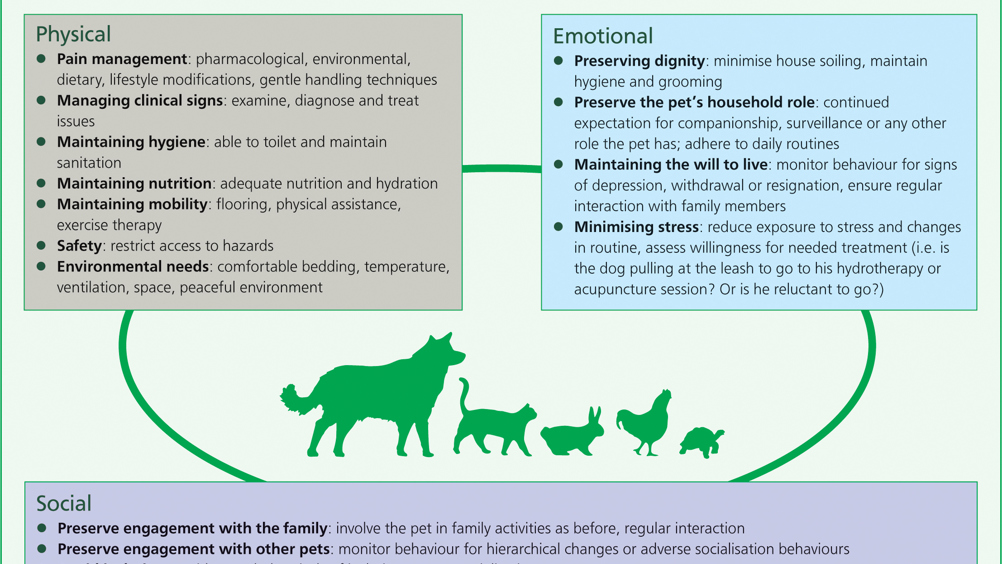

Patients that are in the fifth life stage (end-of-life) often present with multiple problems, which makes them challenging cases. Often, these patients are very vulnerable, and this is sometimes overlooked. This article aims to provide a brief and basic overview of looking after the end-of-life patient, whether at home or in hospital, by utilising a framework adapted from the 2016 International Association of Animal Hospice and Palliative Care, and American Animal Hospital Association Guidelines (IAAHPC/AAHA).

This article aims to give a brief but holistic look at end-of-life management, including some case studies which use an end-of-life framework.

There are thought to be four life stages (young, adult, senior, geriatric). However, it has been proposed that there should be a shift in thinking towards how life stages are classified (Gregersen, 2016a). There should be another life stage: ‘end-of-life’, which can occur after ‘geriatric’, or at any point during a pet's lifetime. Most owners value quality over quantity of life for their pet (Oyama et al, 2008). This study also revealed that owners were highly concerned about detection of perceived suffering in their pet. However, there is a profound mismatch between what owners expect from their veterinary practice in terms of their pet's care at the end-of-life, and what they receive (Gregersen, 2018). Euthanasia, for instance, has been in the top six of RCVS complaints every year, for over a decade (Gregersen 2016b). Historically, veterinary professionals have neglected this ‘fifth life stage’ in companion animals (Hewson, 2018). This lack of support and guidance may result in fear and anxiety for pet owners; and this fear and anxiety may lead to premature euthanasia, or delaying euthanasia, resulting in unnecessary suffering (Gregersen, 2016a).

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting The Veterinary Nurse and reading some of our peer-reviewed content for veterinary professionals. To continue reading this article, please register today.