Obesity is defined as an ‘accumulation of excessive amounts of adipose tissue in the body’ (Zoran, 2010). Clinically patients within the veterinary practice are considered obese if they are 15% or more over the recommended weight for their breed (Colliard et al, 2006).

Obesity is a growing problem in veterinary practice with studies suggesting that anywhere from 18–44% of patients are obese (McGreevy et al, 2005; Lund et al, 2006; German et al, 2010). Obesity is linked to a number of medical conditions including osteoarthritis, diabetes, cruciate ligament tears, tracheal collapse, and cardiovascular diseases (Zoran, 2010; Yaissle et al, 2004; McGreevy et al, 2005).

The conditions associated with obesity are both life limiting and life threatening so it is important that the veterinary profession understands the risks. This article aims to highlight the possible health implications of obesity, as well as suggest ways veterinary nurses can educate owners to help them succeed in weight loss for their dogs.

Health implications of obesity

Endocrine disease

There are a number of endocrine diseases that are associated with obesity including diabetes mellitus, hypoadrenocorticism and hypothyroidism (Burkholder and Toll, 2000).

Diabetes mellitus is strongly associated with obesity in cats however the link is unclear in dogs. It is known that obesity causes insulin resistance in dogs. Gayet et al (2004) found that insulin sensitivity decreased by 44% in dogs that were obese compared with normal weight animals; obesity in dogs leads to insulin resistance, leading to hyperinsulinemia and impaired glucose tolerance (Rand et al, 2004). In addition, it has been shown that dogs are more likely to get type 1 diabetes, lack of insulin production, when obese compared with cats that are more likely to get type 2 diabetes (lack of sensitivity to insulin) (Klinkenberg, 2006).

Hypothyroidism is often cited as a cause for obesity but the link between obesity causing hypothyroidism is not clear (German, 2006). Bensaid et al (2003) studied thyroid hormones in 12 obese dogs compared with 12 lean dogs and found 42% of the obese group had low free thyroxine. These animals however had no clinical signs (lethargy, hair loss, exercise intolerance and difficulty maintaining body temperature) of hypothyroidism so although a link to lower levels has been made it does not necessary mean a disease process will occur. It has also been suggested, however, that obesity causes higher total thyroxine (Daminet et al, 2003), this contradicts Bensaid et al's (2003) findings, and makes a causal link unlikely. Significantly more dogs with hypothyroidism have been found to be obese or overweight (Lund et al, 2006) compared with non-hypothyroid dogs; obesity may occur as a a result of the hypothyroidism and not because of it (Mooney and Shiel, 2012).

Respiratory disease

Respiratory disease is a common issue in overweight humans. There is also evidence that obesity can cause problems in dogs, however most evidence is anecdotal (Zoran, 2010). Tracheal collapse, an inherent weakness in the tracheal rings, is thought to be exacerbated by obesity (Hall et al, 2003); weight loss can be used as a medical treatment of the condition if the patient is obese (Hedlund, 2007). Laryngeal paralysis is also stated to be a respiratory disease associated with obesity (Zoran, 2010). However, it has been suggested that obesity is not the cause but could make the issue worse so should be avoided in these patients (Hedlund, 2007). Airway function at rest is not influenced by obesity (Bach et al, 2007). It has been shown that expiratory airway resistance is greater in obese dogs compared with normal weight animals, but only during times of hyperpnoea, for example during exercise (Bach et al, 2007). This may explain why increased respiratory effort is often noted in obese animals during exercise.

Cardiovascular disease

Obesity and cardiovascular disease are heavily linked in human medicine; the biomedical markers released by adipose tissue are thought to lead to hypertension and coagulopathies putting extra pressure on the heart (Van Gaal et al, 2006). The link between obesity in dogs and cardiovascular problems appears to be less clear cut however. Brown et al (2007) found that obese dogs only had a very small increase in mean blood pressure suggesting that obesity has less of an impact on dogs than humans. Montani et al (2004) suggests that a minor increase in blood pressure is not the only problem seen. It is suggested that fat deposits in obese animals accumulate around and within the heart causing impaired function (Montani et al, 2004).

Orthopaedic disease

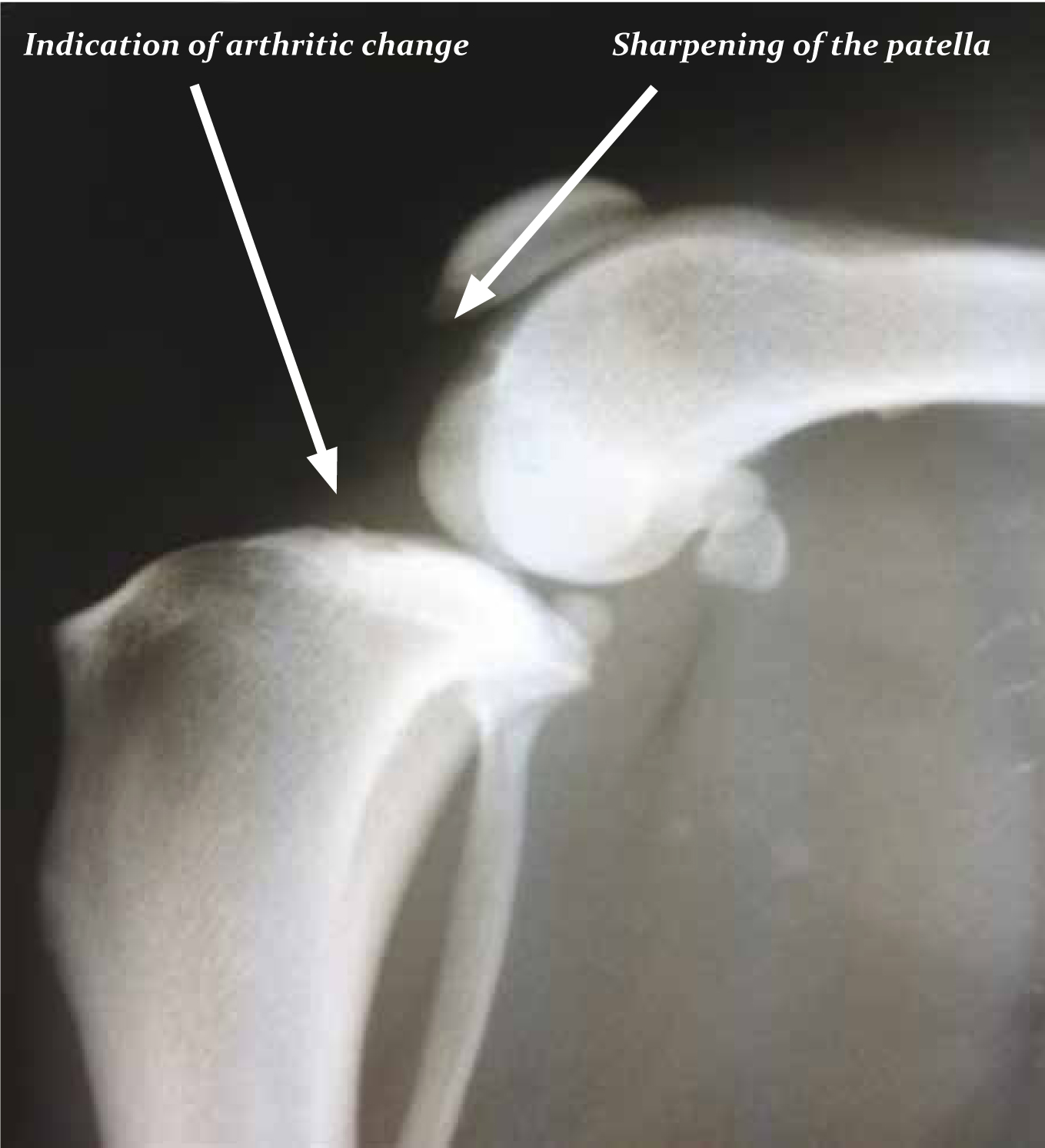

Orthopaedic disease is most often associated with obesity. Overweight or obese dogs were more likely to be treated for ruptured cruciate ligaments (Lund et al, 2006) (Figure 1). In addition, lameness is more likely to occur in obese and overweight dogs compared with normal weight dogs (Lund et al, 2006). Research on humans has suggested this may be due to a change in the joint biomechanics due to increased bodyweight (Marshall et al, 2009).

Osteoarthritis is also more likely to occur in overweight or obese dogs (Lund et al, 2006), and can be reduced with weight loss (Marshall et al, 2009).

Role of the nurse in the obesity fight

Nurse clinics are sometimes used to support and educate owners with overweight pets. These can be difficult clinics and it is important that they are undertaken in a methodical manner to improve the likelihood of success.

The first step is to establish the animal's body weight at the beginning of the clinics. A diagnosis of obesity cannot be successfully made on weight alone as there is often variation between frame size and conformation in breeds which can mean ideal breed weights are inaccurate (Burkholder and Toll, 2000). Body condition scores should be used alongside the animal's weight in order to ensure that an accurate picture of the animal's overall condition is documented before weight loss begins. The WSAVA provide these online (http://www.wsava.org/sites/default/files/Body%20condition%20score%20chart%20dogs.pdf). Measurements of the dog's waist, neck and thorax can also be useful so the owner can see a change in these even if only a small change in seen on the scales.

Once obesity is diagnosed the next decision is what to feed the animal. Establishing the animal's calorific needs at its ideal weight is important at this stage and should be done through the resting energy requirement (RER) equation (70 x ideal BW (kg)0.75). Calculating the RER for the animal at its ideal weight is often the best way to start any weight loss programme (Toll et al, 2010). A 20% restriction from the current intake can be a good starting point (Linder, 2014). This is often a dramatic cut in food and should not occur in one go, regular and effective communication with owners is necessary during weight loss to ensure that the weight loss does not occur too quickly and the owner does not become disillusioned with the process. A rate of 1% of bodyweight loss per week limits risk of nutrient deficiency, loss of lean body mass and rebound weight gain (Laflamme and Hannah, 2005; Linder, 2014).

It may be possible to reduce bodyweight by feeding less of the animal's original food; however there has been research that suggests that this may result in a reduction in vital minerals, vitamins and protein (Byers et al, 2011). It has been suggested that using a reduced level of the animal's own food could result in a starvation state, causing excessive protein loss as well as micronutrient reductions (German et al, 2012); feeding a maintenance diet for weight loss carries the risk of deficiencies as the correct balance of protein and vitamins has not been calculated for the reduced calorie intake (Byer et al, 2011). It has also been suggested that a weight loss programme using the animal's own food is less likely to be successful than one using a commercial weight loss diet due to the animal not feeling full (Byer et al, 2011). High fibre diets, such as weight loss diets, increase satiety in dogs (Weber et al, 2007). Low fibre seems to decrease the feeling of satiety leading to increased begging and scavenging behaviour that puts an increased pressure on the animal–human bond, which can lead to failure of the dieting programme (German et al, 2012). However it has been suggested that weight loss occurs both with high fibre diets and with diets with normal levels of fibre (Diez et al, 2002). The study did find however that using weight loss diets with high fibre and protein resulted in the animals maintaining lean body mass better than those that did not (Diez et al, 2002). Owners must be informed that a high fibre diet is likely to lead to increased faecal output as this may lead to non-compliance.

It is also important that the nurse establishes any treats that are given to the pet. Treats can often be of high calorific content but owners may be reluctant to cut all treats from the dog's diet. Low calorie treats such as carrots or asparagus could be advised to help support the client–dog bond (Linder, 2014). Alternatively a handfull of the dog's dry food can be removed from the daily allowance and used as treats if needed (Linder, 2014).

Nurses will often be asked to educate owners not only in what food to feed their dogs but how often to give it. Advice is normally small meals often, to help animals feel full with less time between meals (Straus, 2009). Bland et al (2009) suggest that dogs should be fed twice a day. Others suggests that food should be given in multiple small amounts, suggesting at least two meals a day 8–12 hours apart (Burkholder and Toll, 2000). Most sources agree that the most important aspect of the feeding regimen is owner compliance. Owners are more likely to comply with a regimen that is normal for them and requires little management of their time; suggesting a person who works full time away from home feed their pet three times a day for example is impractical. The client must be made aware and accept the dog's obese state before taking on a programme; this might mean the very first clinic is a long one discussing the disadvantages to the animal of being obese.

The nurse's role in running clinics is important in order to maintain client compliance. There are a number of different ways to run clinics. It is advised that the weekly clinics are used initially to ensure compliance and help the owners adjust. These can then be changed to bi weekly clinics once the client is comfortable and monthly once weight loss is under way. To ensure commitment owners can be given a chart or graph that the dog's weight loss progress can be recorded on (McCune and Girling, 2006).

Conclusions

Obesity clinics are often run by veterinary nurses so it is important that they are fully aware of the implications on health for obese animals. Successful nurse clinics rely on an accurate assessment of the animal's condition and a good bond between the client and the nurse running the clinic to ensure good compliance and communication.