References

The use of quality of life scales for hospice and end-of-life patients

Abstract

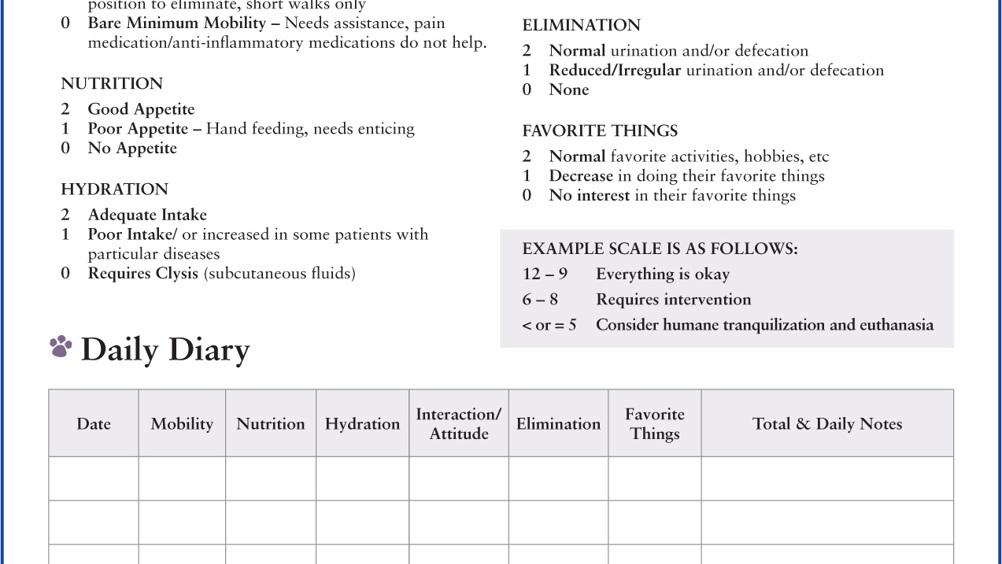

Quality of life scales can be an important tool to the veterinary team. This article explores the use of two quality of life scales, their benefits and limitations using three case studies.

Veterinary practitioners are often asked the questions ‘When is it time?’, ‘How will I know if they are suffering too much?’, ‘I'm not sure whether to put them through any more treatment.’ Often owners are told that they will know when the time comes, but often it is not that clear for the owner, and some patients just will not give a specific sign. Some owners will rely on their veterinary team to help support and guide them through the decision-making process (Mullan, 2015; Gardner, 2017).

Veterinary hospice care is ‘care for animals, focused on the patient's and family's needs; on living life as fully as possible until the time of death (with or without intervention); and on attaining a degree of preparation for death’ (International Association for Animal Hospice and Palliative Care (IAAHPC), 2019). Part of providing hospice care is assessing the quality of life that a patient is currently experiencing.

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting The Veterinary Nurse and reading some of our peer-reviewed content for veterinary professionals. To continue reading this article, please register today.