Protein losing enteropathy (PLE) is not a diagnosis of a specific disease but can be considered a symptom or syndrome of a disease, often gastrointestinal (GI) disease. In this terminology ‘protein’ predominantly refers to albumin and globulins, ‘losing’ expresses their loss, and ‘enteropathy’ refers to disease of the intestine. Therefore, excess proteins are lost through the GI tract (GIT) and will result in low serum protein levels. Although more common in dogs, it can also be presented in cats, with variation in symptoms being mild to severe and life-threatening.

As a result of the complexity and challenges of PLE, patients often require hospitalisation and veterinary nurses may become very involved in the care of such patients. Understanding the syndrome and nursing requirements may improve patient recovery. Definitions to aid understanding of terminology used throughout this article can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1. Definitions of common terminology associated with protein losing enteropathy

| Terminology | Definition |

|---|---|

| Albumin | A protein produced by the liver. Main roles include maintaining COP and binding to, and transporting, substances such as hormones and drugs |

| Ascites | Accumulation of fluid in the peritoneal cavity of the abdomen |

| Colloid osmotic pressure (COP) | Also known as oncotic pressure. The osmotic pressure exerted by large molecules, including albumin, that causes retention of water in the vascular space |

| Effusions | Abnormal accumulation of fluid in body cavities |

| Enteropathy | Disease of the intestine |

| Globulins | A group of proteins produced by the liver or immune system. Main roles include immune function, liver function, coagulopathy function, transportation of substances and enzymatic processes |

| Hydrolysed protein | Protein is broken down into amino acids and peptides, by a chemical reaction involving water |

| Hypoalbuminaemia | Low albumin levels within the blood |

| Hypoallergenic | Reduced likelihood to cause an allergic reaction |

| Hypoglobulinaemia | Low globulin levels within the blood |

| Hypoproteinaemia | Low protein levels within the blood |

| Lymphangiectasia | Dilatation of lymphatic vessels |

| Oedema | Also known as ‘fluid retention’. Abnormal accumulation of fluid within the interstitium |

| Panhypoproteinaemia | Low albumin and globulin levels within the blood |

| Total protein | Measures the sum of all types of proteins within the blood |

Pathophysiology

In a healthy animal, proteins that enter the GIT are digested into amino acids. These amino acids are then reabsorbed by the GIT. As the building blocks of proteins, they are utilised in the synthesis of proteins essential for homeostasis.

In diseases that cause increased permeability in the GIT's mucosa, excess serum proteins will leak into the GIT and be poorly reabsorbed. The unabsorbed proteins are then lost through faeces, resulting in hypoproteinaemia (Nagra and Dang, 2021). Panhypoproteinaemia is defined by the presence of both hypoalbuminaemia and hypoglobulinaemia, therefore resulting in low total protein. This is often a potential indicator for PLE, however some patients may only present with hypoalbuminaemia (Sellon, 2009).

Aetiology

There are three main mechanisms under which diseases and disorders may be categorised, that may cause PLE through disruption of protein reabsorption:

- Increased GIT mucosal permeability to protein

- GIT blood loss

- Lymphangiectasia (GIT lymphatic obstruction). Diseases and disorders that may cause PLE can be seen in Table 2 (Marks, 2007; Nagra and Dang, 2021).

Table 2. Disease and disorders that may cause protein losing enteropathy (PLE), categorised based on the mechanism leading to PLE

| Mechanism categorisation | Potential disease/disorder's causing PLE |

|---|---|

| Increased gastrointestinal tract (GIT) mucosal permeability to protein | Acute or chronic enteropathies, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), neoplasia, parasitic/viral/bacterial enteritis, malabsorption, villous atrophy, gluten enteropathy, chronic GIT obstruction, intussusception |

| GIT blood loss | Intestinal parasites, ulcerations, bleeding tumours |

| Lymphangiectasia; GIT lymphatic obstruction | Primary: congenital or acquired.Secondary: right-sided heart failure, IBD, neoplasia |

Other causes of hypoproteinaemia that are not related to PLE include: hepatic failure; protein losing nephropathies (PLN); exudate losses; haemorrhage; malnutrition; chronic illness; peritonitis; exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI) and hypoadrenocorticism (Mackin, 2010).

Presentation

The clinical presentation of a patient with PLE will depend on the underlying aetiology. Where GIT diseases are the primary underlying cause, patients may present with diarrhoea, vomiting, melaena, haematemesis and/or weight loss. It should be noted that absence of GI signs does not exclude PLE as a differential for hypoproteinaemia (Neiger, 2013; Littler, 2018).

Albumin is essential in maintaining vasculature oncotic/colloid osmotic pressure (COP). Globulins have a lesser degree of oncotic force. Therefore, hypoalbuminaemia results in decreased COP. This causes transudation of fluid from capillaries to extravasculature spaces and may lead to peripheral oedema, ascites or pleural effusion. Occasionally referred to as ‘fluid retention’. It is typically a pure transudate. Albumin values and their categorisation can be seen in Table 3. Furthermore, decreased COP may also lead to hypovolaemia which could progress to hypovolaemic shock (Mackin, 2010; Wray, 2018).

Table 3. Albumin values and clinical signs associated

| Albumin categorisation | Albumin (g/l) | Clinical signs |

|---|---|---|

| Normal range — dogs | 26–25 | None |

| Normal range — cats | 28–29 | None |

| Mild hypoalbuminaemia | 20–26 | Few |

| Moderate hypoalbuminaemia | 15–20 | Few |

| Severe hypoalbuminaemia | <15 | Oedema, ascites, pleural effusion |

With such variation of severity, patients may be managed as an outpatient or they may be considered critical. Craven and Washabau (2019) reviewed veterinary literature between 1977 and 2018 encompassing 469 cases, and found that disease-associated death (including euthanasia) occurred in 54.2% of dogs with PLE.

Diagnostics

It should be remembered that PLE is considered a symptom or syndrome of a disease, and therefore diagnostics may establish GIT protein loss and then continue to determine the underlying cause.

Panhypoproteinaemia or hypoalbuminaemia can be determined through serum biochemistry analysis, although this does not necessarily confirm PLE as such results also potentially occur in PLN and hepatic failure. Therefore, the veterinary surgeon will consider the patient's history and further diagnostics before concluding the patient has PLE (Mackin, 2010; Nelson and Couto, 2020).

Other diagnostics that will likely be performed include: haematology; biochemistry; coagulopathy testing; urinalysis; fluid analysis of effusions; faecal analysis; ultrasonography and radiography (Littler, 2018).

Definitive diagnosis of PLE requires gastric and intestinal biopsies, usually obtained via upper GI endoscopy. Observations can be made during the endoscopy procedure that may confirm suspicions of PLE, but definitive diagnosis cannot be made without histopathology being performed on the biopsies (Littler, 2018).

Treatment

Treatment in PLE cases encompasses symptomatic therapy, nutritional support and treatment of underlying disease. Often the patient will require supportive treatment while awaiting results. In some cases, the veterinary surgeon may prescribe colloid intravenous fluid therapy (IVFT) instead of crystalloids. Colloids contain larger molecules that do not readily leave the vascular space and therefore perform a similar COP role as albumin. Colloid solutions include synthetic solutions, plasma or human serum albumin. It is worth noting that use of crystalloids in cases of moderate and severe hypoalbuminaemia, especially where oedema, ascites or pleural effusion is present, can be detrimental. Although crystalloids would increase vascular volume, the dilution of albumin concentration can further decrease COP, worsening fluid transudation (Mackin, 2010; Smith and Washabau, 2018).

Case and underlying condition dependent, the veterinary surgeon may prescribe other medications (Table 4).

Table 4. Medications the veterinary surgeon may prescribe in protein losing enteropathy (PLE) cases

| Medication | Potential reasoning |

|---|---|

| Immunosuppressives | If an immune-mediated cause is suspected or diagnosed |

| Diuretics | To temporarily aid resolution of severe ascites and effusion |

| Cobalamin (vitamin B12) | Binds to protein and aids absorption in gastrointestinal tract. If serum concentrations are low, supplementation required |

| Antibiotics | If infection or antibiotic-responsive enteropathy is suspected or diagnosed |

| Antithrombotic | PLE patients are at risk of losing antithrombin III and therefore could progress to a hypercoagulable state, increasing the risk of a thromboembolism |

In cases with lymphangiectasia, dietary fat restrictions are required. In cases with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), often a select protein diet is required. If a patient has concurrent lymphangiectasia and IBD, the dietary requirements can be challenging to meet. Therefore, use of a hypoallergenic diet, which contains hydrolysed protein sources and moderate dietary fat, is recommended. In severe cases of cachectic patients with severe hypoalbuminaemia and intractable vomiting or diarrhoea, parenteral nutrition may be considered (Marks, 2007; Nelson and Couto, 2020).

Nursing considerations

Published literature encompassing nursing considerations for PLE is minimal, however this could be attributed to PLE being a syndrome or symptom, rather than a disorder or disease, and can present with various clinical signs. Therefore, PLE patients must be considered individually and nursing interventions will depend on presenting symptoms and involve the administration of prescribed treatments. The nursing considerations discussed below are reflections from the author's experience in practice and may also be beneficial to cases not involving PLE.

Diarrhoea management and fluid balance assessment

Diarrhoea is a common symptom presented in cases with PLE. It is essential where possible, that the patient is given ample opportunity to toilet outside, with some practices walking out every 4 hours. However, in cases with diarrhoea, this may be increased to every 2 hours or when the patient shows signs of distress that may be interpreted as the patient needing to toilet, such as increased vocalisation, pacing or scratching at the kennel door.

If soiling is a risk, the following nursing interventions may be implemented:

- Tail bandage of one cohesive layer — change twice daily or sooner if soiled, particular care of compression if oedema present

- Clipping of hair around perianal area — individually assess as hair may serve as a beneficial barrier

- Bathing of perianal area — gently bathe and dry when soiled

- Barrier cream to perianal area — apply as frequently as required, particularly after bathing.

- Faecal foley catheter.

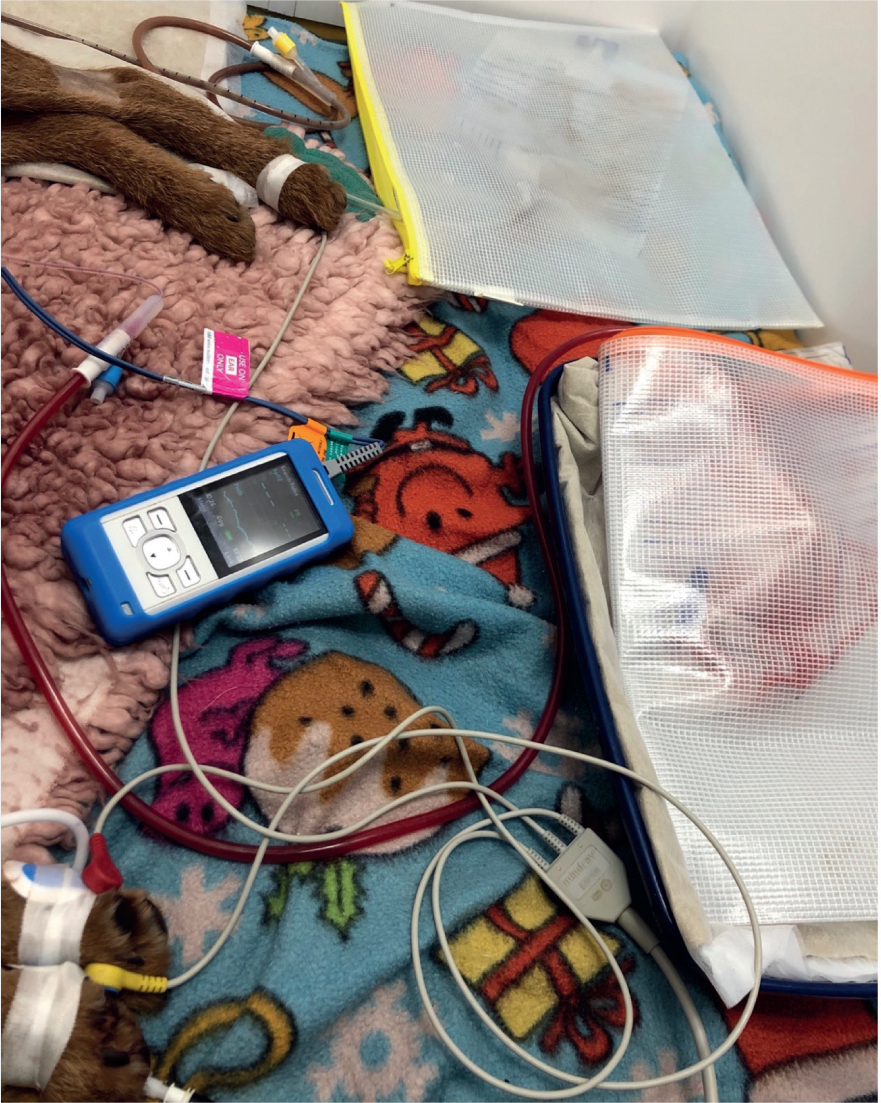

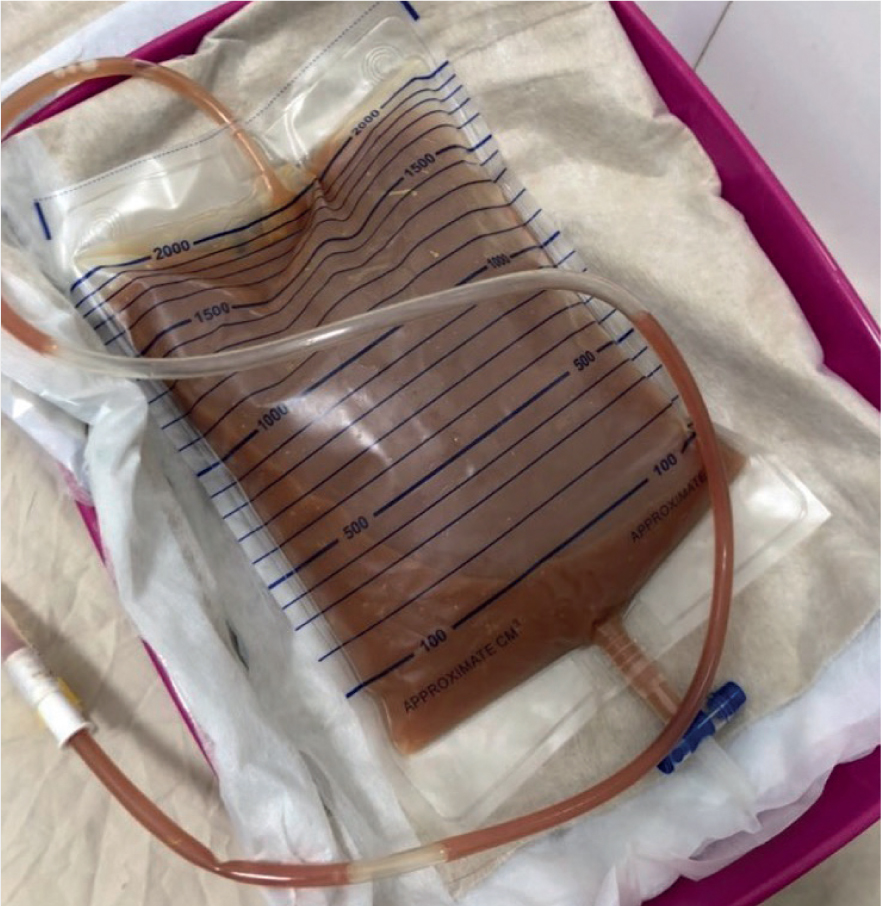

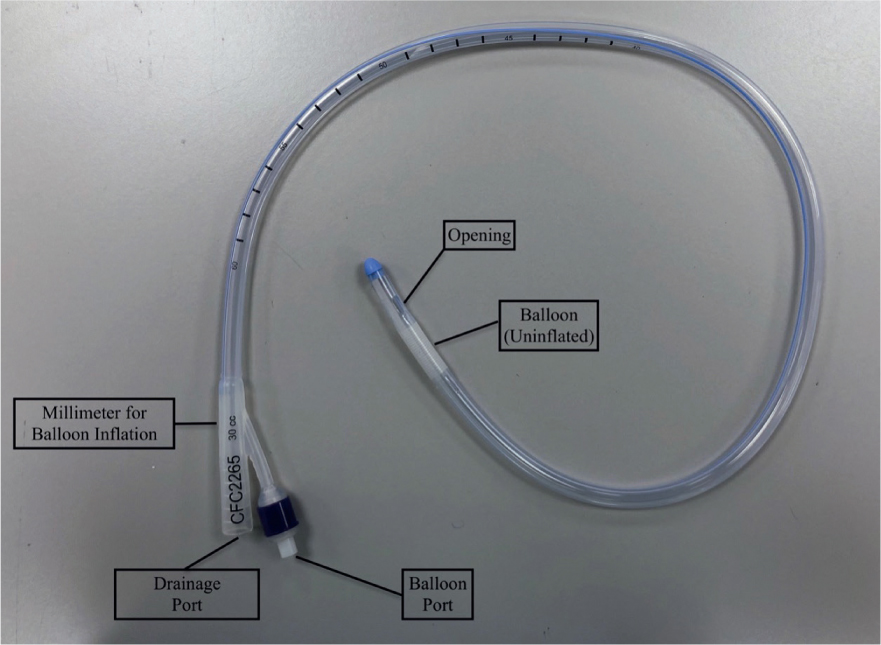

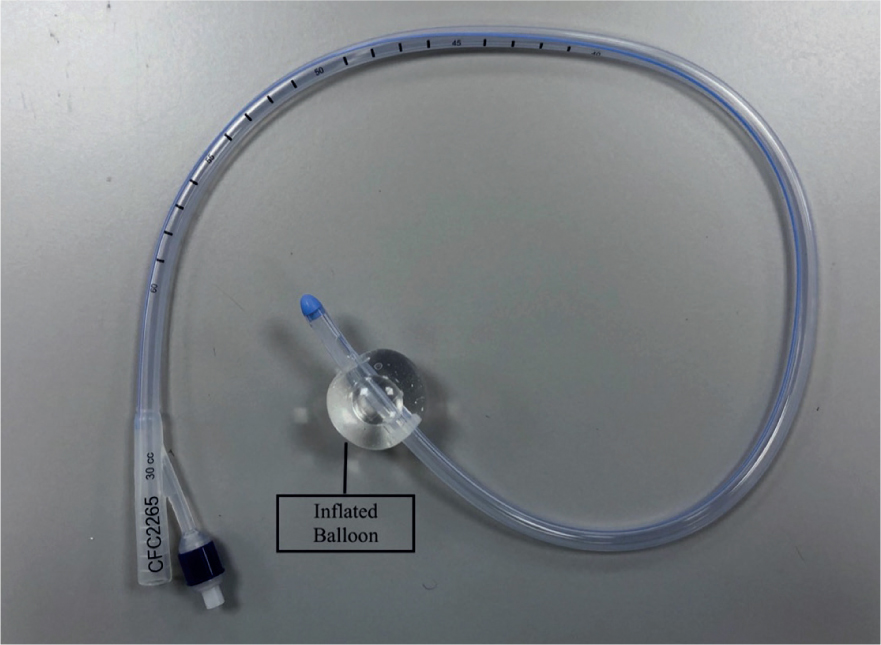

If the patients' stool is of a watery consistency, a faecal catheter attached to a closed system could be a strong consideration. Although not common within veterinary practice, they are well utilised within the human medical field. Specific faecal catheters can be sourced, but indwelling foley catheters can also be used (Gray, 2018) as seen in Figures 1, 2, 3 and 4. Benefits of faecal catheters include:

- Prevent faecal soiling and scalding

- Reduce requirement for walking (particularly in recumbent or heavily depressed patients)

- Improve infection control and minimise transmission

- Reduce risk of patient acquiring a urinary tract infection

- Reduce contamination of bedding, cleaning, washing and the requirement of moving large recumbent patients to change bedding

- Enable reliable measurement of fluid losses

- Retain odour.

As a result of little research in the use of faecal catheters in veterinary patients, great caution is essential as there is risk of ischaemia of the colon from inflation of the balloon (Gray, 2018). Some standard operating procedures (SOPs) will advise that faecal foley catheters are deflated, repositioned and re-inflated every 2–4 hours to reduce the risk of colon ischaemia. Furthermore, the content can be emptied and measured for fluid balance assessment. Indwelling urinary catheters may also be placed in patients that are recumbent as seen in Figure 1. It is important to ensure there is no cross contamination with strict hygiene performed and personal protective equipment (PPE) worn.

Nurses can suggest the use of faecal and urinary catheters in cases they may feel would be advantageous, and if competent may place them under veterinary surgeon direction.

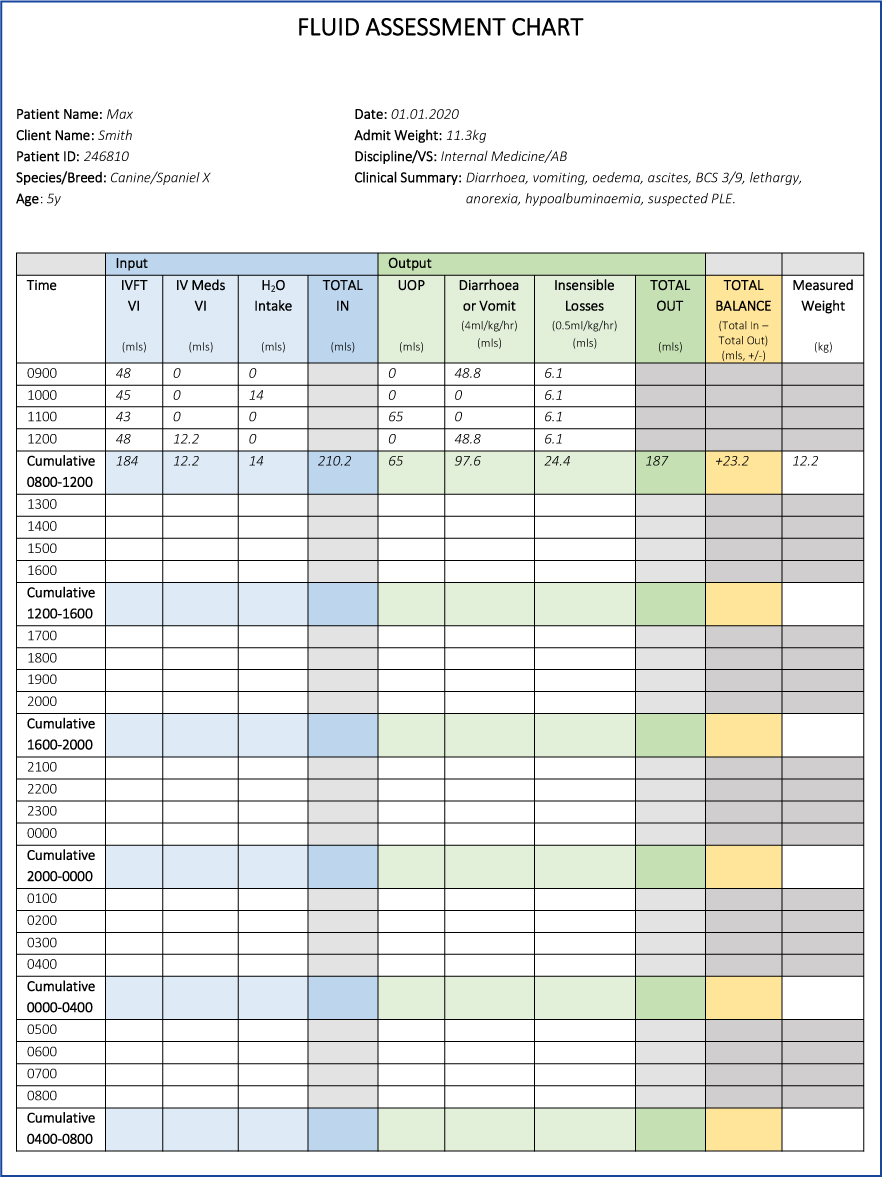

Fluid balance assessment should be implemented every 4 hours. At this interval, the patient should have the following assessed:

- Weight

- Volume infused (IVFT, constant rate infusion (CRI), intravenous medications)

- Volume consumed (water, liquid diet)

- Measurable volume losses through closed systems (diarrhoea, urine) or calculated per episode at 4 mls/kg/hour (diarrhoea, vomit)

- Insensible volume losses (evaporative losses, exhalation, perspiration — 0.5 ml/kg/hour).

The calculated result indicates whether the patient's fluid management is balanced, in deficit or excess, and may aid fluid therapy decisions. Figure 5 is an example sheet showing calculations performed at 4 hour interval, when the veterinary surgeon may evaluate the patient's IVFT.

Nutrition

Nurses should monitor for any signs of nausea and report to the treating veterinary surgeon. Antiemetics may be prescribed.

Tempting the patient to eat is an important part of nursing, particularly in inappetent cases. Some PLE cases may be restricted to a hypoallergenic diet. Such diets can be warmed, water added to change consistency, offered in different bowls or in different environments, such as in a separate room or outside when walked.

If the patient continues to refuse food, a feeding tube, such as a naso-oesophageal (NO), naso-gastric (NG) or oesophageal (O) tube, may be placed and feeding commenced as soon as possible. This is because enterocytes that line the GIT atrophy quickly without direct nutrition. This can lead to GIT breakdown and permeability, which can result in bacterial translocation and potentially sepsis. Enteral nutrition is preferred over parenteral nutrition where possible because of the importance of enterocytes acquiring direct nutrition (Firth, 2014; Chan, 2020). Nurses may place NO or NG tubes under the veterinary surgeon's direction. It is important that nurses are familiar with the maintenance of such feeding tubes.

Oedema and effusions

Nursing considerations for oedema may include:

- Keeping limbs slightly elevated

- Avoidance of blood pressure checks on limbs most oedematous

- Avoidance of intravenous catheter (IVC) placement or venepuncture

- Care with compression from tape or dressings (IVCs, O tubes, central lines, wounds)

- Regular walking or passive range of motion (PROM)

- Gentle massage techniques such as effleurage distal to proximal

- Deep comfortable mattress (also providing comfort for ascites) (Craven and Washabau, 2019).

Figures 6 and 7 demonstrate pitting oedema of the abdomen.

If peripheral oedema is severe or the patient is requiring repeated blood sampling or aggressive fluid therapy with multiple CRIs, the veterinary surgeon may consider a central line (e.g. central venous catheter or peripherally inserted central catheter), which requires close nursing care. Therefore, nurses should familiarise themselves with associated SOPs (Gray, 2018).

With risk of effusions occurring, it is important that nurses know the clinical signs and alert the veterinary surgeon if they suspect development, recurrence or worsening of effusions. Causes for concern include: abdominal changes in shape or size; increased respiratory effort or fluid from the nose.

Wound implications

Hypoalbuminaemia is associated with delayed wound healing (Hollis and King, 2011; Pendergrass, 2017). Therefore, susceptibility should be considered, such as with faecal scalding or other pre-existing wounds.

Infection control

As Table 2 demonstrates, a possible infectious cause may be present and therefore the patient should be barrier nursed with strict hygiene protocols. Where practices can facilitate, such patients may be placed in isolation (e.g. parvovirus), however this may depend on resources and whether the patient is considered stable or critical.

Reverse barrier nursing may also be required where the patient is considered immunocompromised as a result of neutropenia or immunosuppressant medication (Gray, 2018). However, a patient that may not be neutropenic on initial blood analysis, may become so while hospitalised and therefore strict hygiene is essential in all cases. Furthermore, cytotoxic medications may be administered for immunosuppressant purposes. It is essential that a SOP is in place and adhered to.

Conclusion

PLE is a variable syndrome that nurses may encounter within practice. In cases where hospitalisation is required, nurses play a significant role in their care. With a high fatality rate of >50% (Craven and Washabau, 2019), understanding the syndrome and potential consequences enables nurses to consider how the patient can be most effectively cared for, identify deterioration, minimise complications and ultimately contribute to a successful outcome.

KEY POINTS

- Protein losing enteropathy (PLE) is not a diagnosis but can be considered a symptom or syndrome of a disease or disorder, often from gastrointestinal origin.

- PLE terminology: ‘protein’ predominantly refers to albumin and globulins, ‘losing’ expresses their loss and ‘enteropathy’ refers to disease of the intestine.

- PLE can vary from mild to severe and life-threatening.

- Hypoalbuminaemia reduces colloid osmotic pressure, potentially leading to oedema, effusions and/or hypovolaemia.

- An understanding of PLE and potential consequences can improve the nursing of PLE patients and therefore the outcome.