Cancer is an insidious, nefarious and obstinate disease. It represents a major cause of canine death and accounts for 27% of all deaths in purebred dogs in the United Kingdom (Adams et al, 2010). Cancer is an intricate set of biological aberrations that originate in the nucleus of cells and are not completely understood. It results in the uncontrolled and reckless growth of destructive cells that overwhelm the body as they accumulate (Balducci, 2007). The etiopathogenesis (cause and progression) of cancer in animals is likely to be multifactorial, but may involve both genetic and environmental risk factors. Dobson (2013) stated that the limited genetic diversity seen in purebred dogs facilitates genetic linkage, citing the breeds with the highest proportional mortality for cancer as the Irish water spaniel, Flat-coated retriever and Hungarian wirehaired vizsla. As with humans, exposure to environmental contaminants such as cigarette smoke, asbestos and other pollutants has been associated with an increased risk of developing cancer in pets (Moore and Frimberger, 2010).

Presenting the diagnosis

Clients need time to adjust to the idea that their companion may have a terminal illness. Chun and Garrett (2007) suggested that small ‘sound bites’ work well when advising an owner that there may be a malignant process involved, and that mentioning the possibility of cancer as a differential before a definitive diagnosis had both pros and cons. While it is important to avoid inducing unnecessary worry and fear by suggesting the possibility of cancer, it can be helpful to prepare an owner for the diagnosis when the likelihood of such a finding is high. The provision of a neoplastic differential may help an owner to adjust to the idea and deal with the diagnosis in a more coherent and proactive manner once it is confirmed (Chun and Garrett, 2007).

It is essential to remember that clients, as well as veterinary personnel, have their own preconceived ideas about the term ‘cancer’ — which are usually negative. These ideas stem from previous or current experiences of the disease, as well increasing research and its portrayal by the media. Therefore, even with prior notice that the diagnosis could be cancer, some clients may still be extremely shocked and may only be able to take in small bits of information. Presenting the diagnosis in a way that gives the client time to adjust and asking for permission to provide further information is essential. For example:

‘Unfortunately, as we suspected, the results have come back as lymphoma. This is one of the most common cancers we see in dogs. The positive news is that there are treatment options available, but unfortunately, it is not curable. Would you like to discuss further testing and treatment options now, or would you prefer some time and we talk later?’

If veterinary personnel fail to win client trust during delivery of a cancer diagnosis, effective case management may be compromised. Therefore, the offer of time and space can help with the owner's transition from grief to taking an active role in making treatment choices for their pet (Chun and Garrett, 2007).

Offering treatment options

The key aspect to guiding clients through the diagnosis and treatment of their companion is to be open and honest in the information provided, and to explain things in language that is accessible to the client. As experienced veterinary personnel, it is easy to forget that commonly used terminology within the profession such as neoplastic, malignant and staging may not be understood by the average pet owner. Taking time to explain things in ‘layperson's’ terms is essential to clarify understanding. Chun and Garrett (2007) stated that clients can become overwhelmed with treatment options and discussion, and may become too distraught or even embarrassed to ask for explanations about words they do not understand.

Often, a diagnosis of cancer can be made after limited testing, such as an aspirate of a lymph node revealing lymphoma. Staging, or evaluation for the systemic extent of a cancer, is however critical in making further treatment decisions and in more accurately predicting the prognosis for the patient. Diagnostic tests used for staging include radiography, ultrasonography, computed axial tomography and cytological examination of needle aspirates of regional lymph nodes and bone marrow. Recommendations for further indicated tests such as staging, and explanations of their benefits and associated costs, along with what they may reveal, can all be covered in the first meeting after the initial diagnosis has been made. This should enable clients to make informed decisions regarding the pursuit of additional testing or therapies. It must be remembered that some clients will make a decision not to pursue treatment based on this first discussion alone, and would therefore not appreciate the suggestion of additional testing that would not make a difference to their decision-making process in the end. It is essential that veterinary personnel accept that choosing not to treat a pet with neoplasia is always a reasonable decision and, ultimately, is the client's decision alone. It is important, however, to ensure that a decision not to pursue treatment is not based on misconceptions surrounding the disease or its treatment. Therefore, owner education regarding how well companion animals tolerate most medical, surgical and radiation therapies used against tumours is essential. Explaining to clients using statistics they can understand can be of benefit here; for example, informing clients that more than 75% of dogs treated with chemotherapy have no side effects, and that most of the remaining 25% that may have side effects can be managed optimally at home, may change an owner's decision about treatment (Chun and Garrett, 2007).

Another reason why an owner may elect not to pursue treatment is that achieving a cure in veterinary oncology is not common. More often, the concept of a ‘disease-free-interval’ (DFI) is discussed, or the period of time in which a patient demonstrates no obvious clinical signs of its cancer, with 1- or 2-year survival times often presented concurrently in veterinary literature surrounding DFI (Ciekot, 1995). It is essential, therefore, for veterinary personnel to understand that the value of any additional time that a treatment can provide for a client and their companion can only be determined by the client. For some owners, an additional year of life would not be considered a good enough reason to pursue treatment. Conversely, however, some owners would be grateful to have their pet for an extra month or two. Financial implications must also be considered, which means that some owners may have to decline certain aspects of care, such as staging, in order that they may be able to afford other treatments, such as chemotherapy. Discussion of therapeutic options therefore must include an estimate of fees.

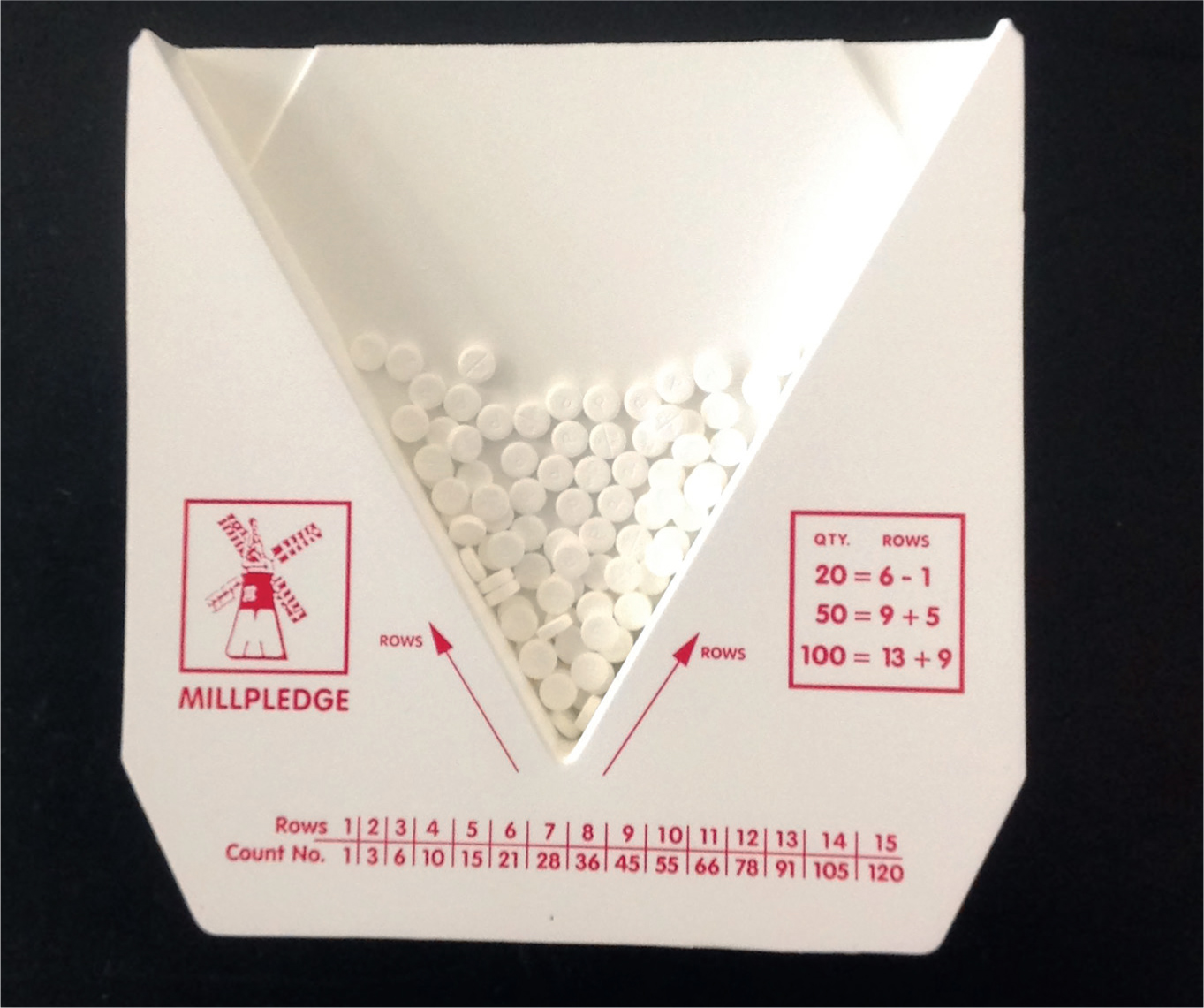

Palliation with anti-inflammatory agents and sending a pet home to comfortably live out their remaining time is an option that can be offered to owners for financial, emotional and logistical reasons (Figure 1). Such a decision can enable owners to come to terms with the situation and empower them to help their pet despite other options not being feasible. Quality of life (QoL) must of course be monitored closely in such a situation. Regular communication between the owner and the veterinary team is essential to keep the pet as comfortable as possible, and to assist the owner in their decision for timely euthanasia. Paraneoplastic syndromes are tumour-associated changes that have significant systemic effects leading to reduction of the patient's general condition and QoL (Simon, 2006). The treatment of a paraneoplastic condition may be considered even if other therapies are not pursued, as this may lead to an amelioration of QoL even in the absence of tumour control.

Methods of therapy

It is beyond the scope of this article to detail all potential therapies for neoplastic disease. Common modalities used to manage the disease include surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy and, will be discussed briefly.

Surgery

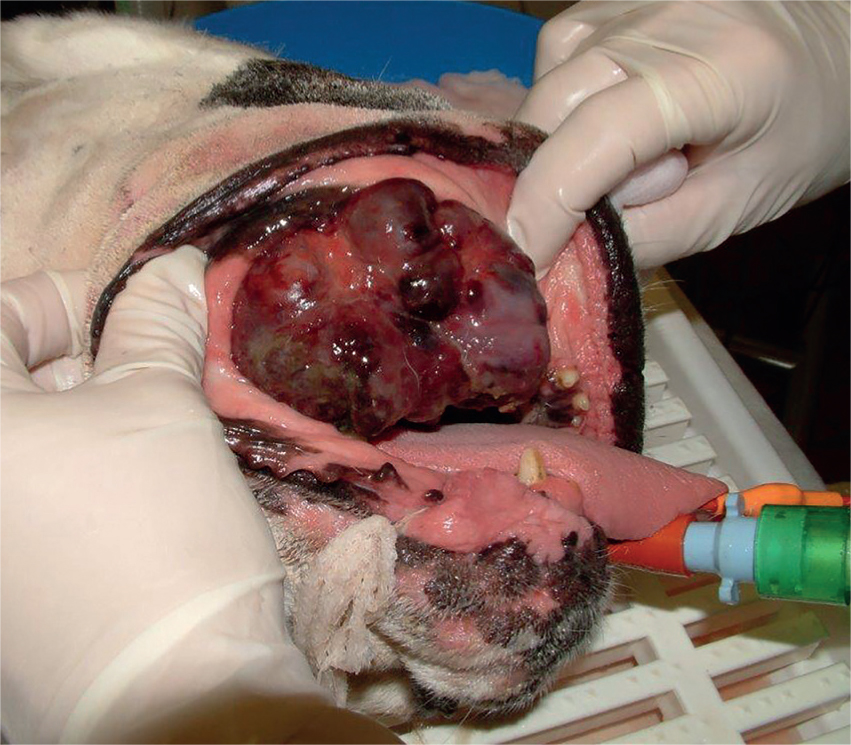

Surgery is often the modality of choice for localised or regional cancer, and the surgical technique selected will vary depending on the site, size, and stage of the tumour (Figure 2). Ciekot (1995) suggested that the first surgery has the greatest chance of cure, and the primary objective is always removal of all tumour, achieving good resection margins while preserving function and cosmetic appearance. It is important to discuss with owners the potentially disfiguring effects of cancer surgery, such as those caused by limb amputation or partial mandibulectomy. When the benefits of surgery are correctly explained to the owner and the potential for disfigurement discussed prior to surgery, the change in appearance will often be viewed by owners as a fair exchange for the possibility of prolonged life of their pet.

Surgery can also be used as part of a palliative treatment plan. The goal of palliative surgery, as in all palliative measures, is primarily to ameliorate or restore the patient's QoL, and not to achieve a complete tumour resection (Simon, 2006). For the most part, palliative surgical interventions encompass procedures that lead to an alleviation of pain or functional improvement of an organ or organ system. In this context, Simon (2006) pointed out the significant importance that the patient's morbidity created by the surgical intervention does not outweigh the expected increase in QoL.

Examples for palliative surgery in veterinary oncology are numerous and include large, ulcerated tumours. Marginal surgical resection can lead to an improvement of tumour-associated pain and reduce the risk of local or systemic infection (Simon, 2006).

Radiation therapy

With the exception of a few radiopharmaceuticals (e.g. radioiodine), radiation is a local treatment, meaning that its effect is limited to the area to which it is directed. Therefore, care should be taken to ensure the animal is staged properly to delineate the extent of the primary cancer, and that no metastases are present (Moore and Frimberger, 2010). Localised tumour types that are often treated with radiotherapy include mast cell tumours, squamous cell carcinoma and meningioma. Side effects from radiotherapy include some fur loss at the treatment site and possibly additional skin pigmentation; while these are purely cosmetic, and of no detriment to the patient, they should be discussed with the owner prior to commencing treatment. Dermatitis, which resembles sunburn, can however occur in some patients after radiotherapy, which can prove very painful. Keeping the area clean and preventing self-mutilation is paramount here; analgesia and antibiotic therapy may need to be prescribed (Moore and Frimberger, 2010). Radiotherapy as a single modality is only generally used for tumours that are likely to remain localised. Therefore, radiotherapy is most often used in conjunction with surgery or chemotherapy, and is often used in the palliative setting for the management of appendicular osteosarcoma where amputation is not considered an option (Simon, 2006).

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the principal modality used to treat systemic cancers such as haematological malignancies and metastatic cancers (Moore and Frimberger, 2010). Chemotherapy to control a neoplasm rarely obtains a cure but complete or partial remission is often feasible, with the period of remission ranging from 6 months to 24+ months, depending on the tumour type (Chun, 2014). Owners must be made aware that at some point in the future, the tumour will come out of remission, and the animal will relapse. This type of therapy often invokes fear as a result of pre-existing ideas among owners; hence it is essential to address and allay such concerns before commencing treatment. Chun (2014) stated the importance of clients understanding ‘up front’ the number and frequency of visits, how much they may spend on the therapy, and the potential side effects.

Chemotherapy drugs affect, in general, rapidly dividing cells. Therefore, the most common side effects observed include gastrointestinal (GI) upset, myelosuppression and hair loss. GI upsets typically manifest as inappetance, nausea, vomiting and/or diarrhoea, hence anti-emetics or GI protectants may be prescribed for the patient.

Myelosuppression arises secondary to damage to the rapidly dividing marrow stem cells, with cells with the shortest life span being most susceptible. Myelo-suppression is therefore most commonly manifested as a decrease in neutrophil and/or platelet counts. Chemotherapy treatment will need to be delayed if myelosupression is significant and it is important that owners are made aware of this. Alopecia is a common side effect observed in human chemotherapy treatments and often causes pet owners concern. Typically, chemotherapy-associated hair loss in pets occurs in breeds with continuously growing hair such as poodles or some terriers (Chun, 2014). The hair loss is generally not complete and, with most dogs, it is minimal. Cats may lose their longer guard hairs or whiskers during treatment but total hair loss is very rare.

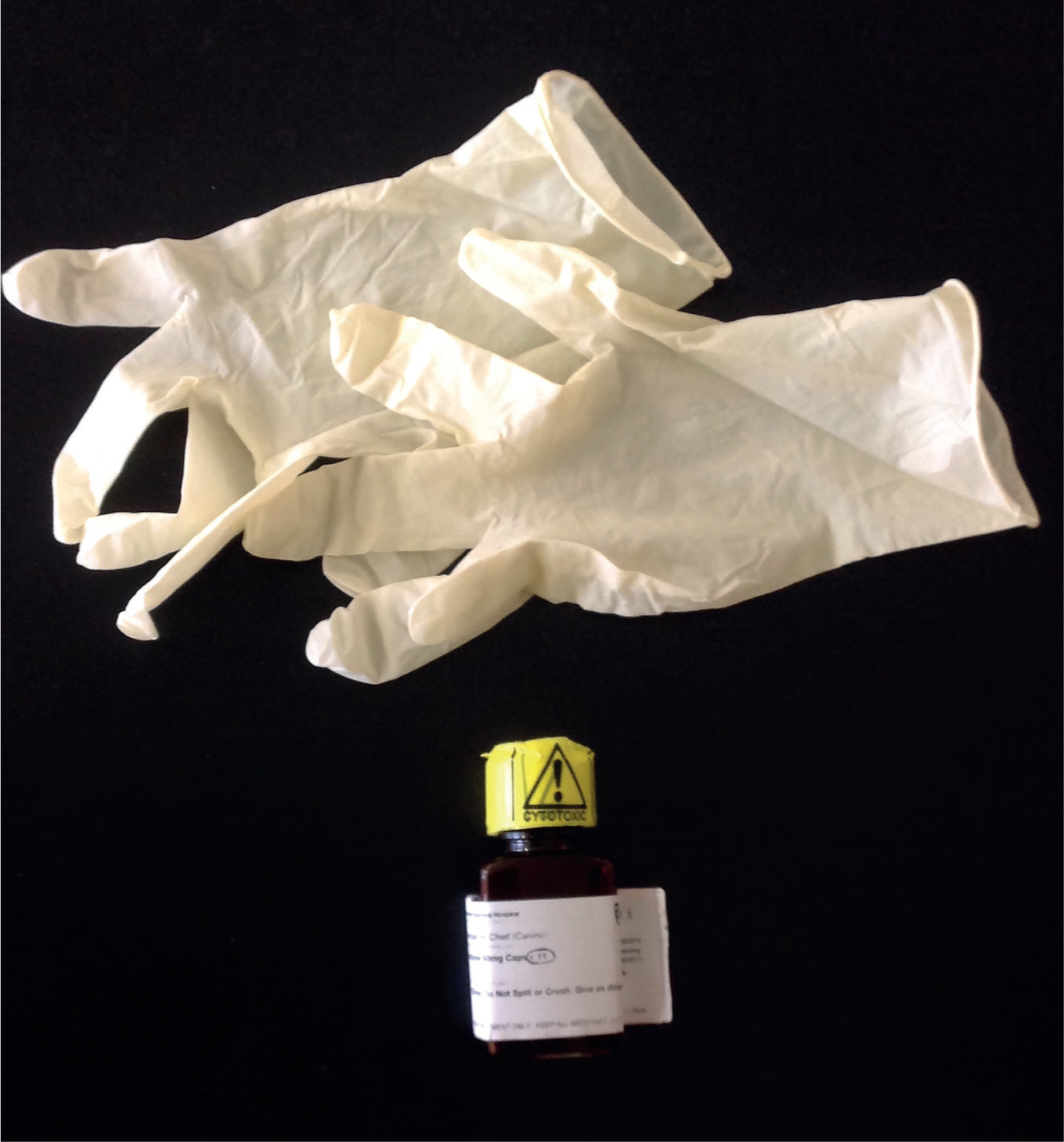

The potential of owner exposure to chemotherapy agents is very small; however, clients must be informed of the precautions to take to maintain little or no exposure. Owners should be advised to treat all of their pet's bodily fluids as potentially harmful. The amount of drug excretion will vary significantly depending on the treatment given; however, the body excretes more by-products during the first initial days following treatment. Owners should therefore discourage their pets from licking them and take care with exposure to waste products. With regards to the management of waste, owners should be advised that solid waste can be flushed down the toilet or bagged and put into domestic waste. Gloves must be worn for disposing of waste and areas can be cleaned with household bleach once waste has been cleared. Pets should also be encouraged to urinate on grass wherever possible (Tancock, 2010). If the patient is to be discharged with oral chemotherapy drugs, the medication bottle should be clearly labelled as cytotoxic and the owner should be provided with gloves to wear for administration (Figure 3). Chemotherapy agents should always be stored in the original container and must be kept out of the reach of children and pets, ideally in a secure receptacle away from the kitchen or bathroom to avoid accidental ingestion. Used gloves and empty chemotherapy containers can be placed in a plastic bag and disposed of with normal household refuse. Any unused chemotherapy drugs should be returned to the veterinary practice for safe disposal. Clients who may be pregnant, or trying to become pregnant, should be excluded from the handling of chemotherapeutics.

Providing support

While it is the veterinary surgeon who will deliver news regarding diagnosis and treatment options, all members of the veterinary team, including receptionists and veterinary nurses, must show compassion and empathy towards clients as they deal with this distressing situation. Empathy, defined by Chun and Garrett (2007) in this context as the recognition and comprehension of another's emotional situation, is a powerful tool. Empathy differs from sympathy in that sympathy implies one has compassion for someone but does not necessarily feel their emotions. Empathy does not mean that you feel what the client feels; however, it does mean that you can try to imagine how the situation would be from the client's point of view; the ability to ‘stand in someone else's shoes’.

As previously discussed, clients will arrive at the veterinary practice with images, knowledge, emotion and even personal experience surrounding cancer. The author has experienced a number of situations in veterinary practice in which one of the animal's owners has died of cancer and the remaining owner is now faced with such a prognosis in their pet, or the owner of the animal has battled the disease themselves and experienced a number of adverse side-effects more commonly seen in human cancer therapy. The author has also experienced the loss of her own companion to lymphoma. While being acutely aware of the disease and its potential outcomes, she greatly appreciated the compassion and support shown to her and her companion by all members of the veterinary team throughout the treatment and, ultimately, euthanasia process.

Misplaced optimism

A common and frustrating aspect of communicating with oncology clients is the occurrence of ‘bargaining’ for a positive outcome. Bargaining is a recognised stage of the grief cycle as defined by the Swiss-American psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross (1969) and may involve such actions as contacting multiple veterinary practices for opinions, or excessively using the internet to search for a known cure. This behaviour is understandable; however, such optimism is usually misplaced. While still remaining positive, it is essential that veterinary personnel remain open and consistent with clients, stressing the condition and prognosis and ensuring that clients understand the gravity of the situation. When faced with such questions as ‘Don't you think Barney could be one of the dogs that does beat cancer?’, remaining positive but also realistic may be achieved by providing such responses as:

‘It would be great if Barney was cured of this disease, but the odds of this are very slim. However, with the appropriate treatment, and barring major complications, there is a chance that we may be able to help Barney outlive his prognosis’.

QoL scales

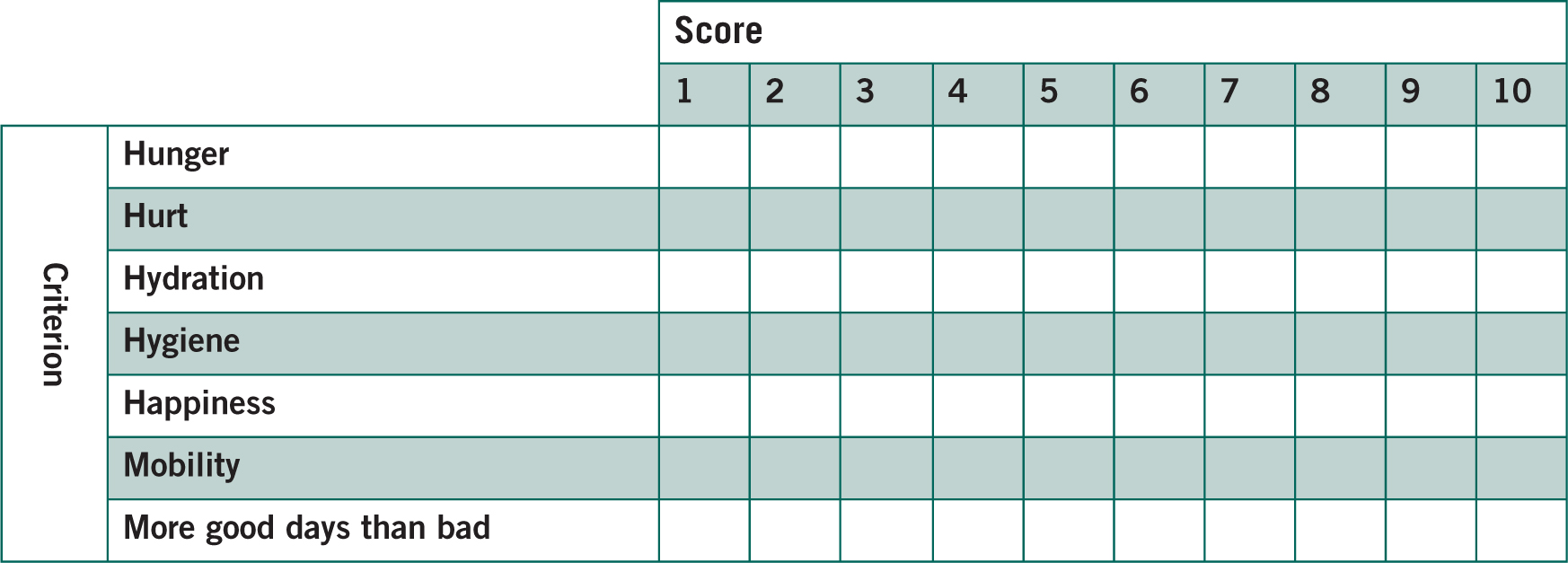

There is a need for ongoing assessment of QoL with oncology patients. Villalobos (2011) devised a QoL scale for use specifically with oncology patients known as the HHHHHMM scale, which represents Hurt, Hunger, Hydration, Hygiene, Happiness, Mobility and More good days than bad. The scale (Figure 4) lists all of the above factors from 1–10, 10 being the best possible score. A score of over 5 is deemed as an acceptable QoL for each factor; however, the closer to 10 each factor scores, the better. If a factor decreases its score, this does not mean that the animal has an unacceptable QoL and euthanasia must be considered; it simply means that reassessment of that factor is required, as well as a probable change of medication, nursing intervention or home modification. The use of owner-led QoL assessment, undertaken within the home environment, and combined with regular veterinary assessment, will greatly facilitate the best possible care and welfare for the animal.

Conclusion

While each veterinary oncology patient is different, the strategies used to present the diagnosis and treatment options are similar. Clients require empathic, honest, and consistent communications that establish realistic goals and focus on quality of life. A collaborative approach, with the veterinary team educating the client about the disease, and then working with them to come up with the best way forward for both the pet and owner, is advocated. Veterinary staff are in a unique and privileged position to make a difference, not only to the oncology patient, but also family members who love and care for them.