In March 2010 Melbourne experienced one of the most severe storms in living memory. High winds, torrential rain and huge hail stones caused widespread damage across much of the city and surrounding suburbs. One of the hardest hit suburbs was that of Lysterfield in Melbourne's south east. With almost every house in the suburb sustaining some sort of damage it was not surprising that there would be some casualties but no one could have predicted one turtle's plight.

Initial presentation

On the day after the storm Tatiana, a 13-year-old female Eastern Long-neck Turtle, was presented to the Karingal Veterinary Hospital after her owners found her seeking shelter under some trees in their back yard. On examination she weighed 311 g and was considered to be in excellent body condition. She was bright and alert. When placed on the consulting table she readily walked and showed no evidence of lameness. She had an approximately 3 cm depressed shell fracture on the left side of her carapace (Figure 1). Closer examination of the shell fracture revealed that is had penetrated the coelom and the left lung was visible. There was a moderate amount of contamination of the wound with leaf litter and dirt. Tatiana also had a slight bilateral epistaxis. This was considered to be secondary to probable lung trauma she had sustained as she had no evidence of head trauma.

Given the size and location of the shell fracture it was suspected that Tatiana had been struck by one of the large hail stones that had fallen in the storm the day before. She was housed in an outdoor enclosure that had been obviously damaged in the storm.

Treatment

With her owners’ consent Tatiana was admitted to Karingal Veterinary Hospital for treatment.

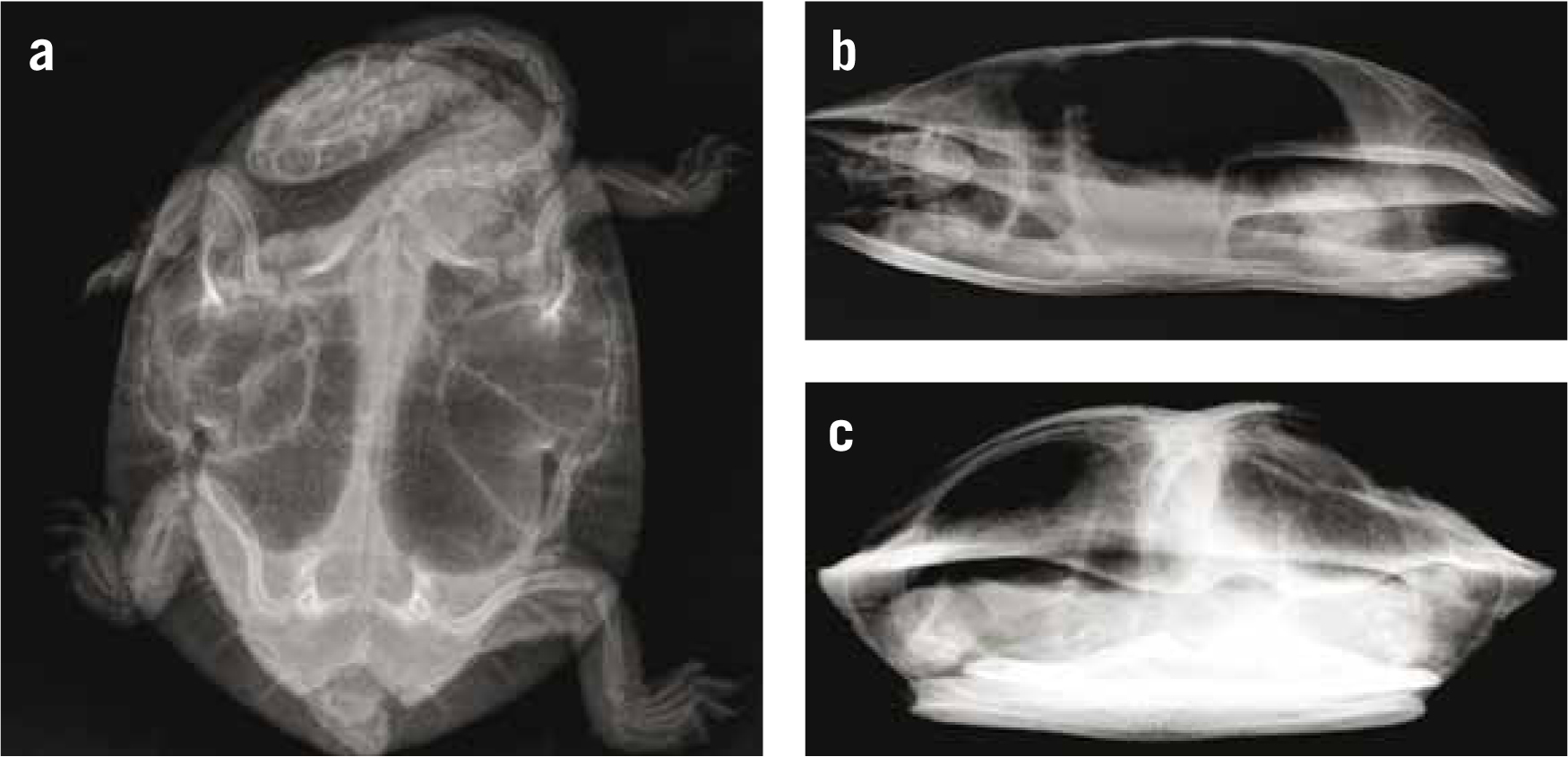

All gross contamination was manually removed from the wound using a small pair of forceps. Radiographs were taken to assess for any internal damage. Three views of turtles are required to allow a full assessment of the pectoral and pelvic girdles, the internal organs and in particular the lungs. These are a dorsoventral view, a standing lateral view and a standing skyline view (Figure 2). Other than the obvious shell fracture no other abnormalities were detected.

The shell fracture was further cleaned using warmed sodium chloride solution (0.9% NaCl, Baxter, Australia) to remove all the contamination. Particular attention was paid while lavaging the area to avoid driving any foreign material into the body cavity.

Shell fractures in turtles should be treated as contaminated wounds and as such should not be immedi-ately closed until the veterinarian is satisfied that all the foreign material has been removed and any potential infection has been eradicated (Adkesson et al. 2007; Vella, 2009). To achieve this in Tatiana's case she was administered the antibiotic, ceftazidime (Fortum®, Glaxo-SmithKline, Australia) at a dose rate of 20 mg/kg via a subcutaneous (SC) injection every 3 days for a total of 10 doses. Silver sulfadiazine (Flamazine™, Smith & Nephew, Australia) was applied to the cleaned wound daily after cleaning with a 0.05% solution of chlorhexadine (Chlorhex C, Jurox, Australia). The wound was dressed with cotton gauzed swabs soaked in chlorhexadine and secured in place using Co-Plus Self Adherent Bandage (Smith & Nephew, Australia) (Figure 3). These bandages were changed daily for the first 5 days. At day 6 it was felt that all the debris had been adequately removed. The wound was then covered with a non-adherent dressing (Melolin™, Smith & Nephew, Australia) and held in place with Co-Plus bandage. This was changed every 3 days.

The provision of analgesia is vital in managing cases of shell trauma. It should be remembered that the shell is effectively a turtle's rib cage and is a living tissue with nerve supply. Wounds to the shell, particularly fractures, are very painful and so analgesia must be provided. Tatiana was given butorphanol (Torbugesic®, Pfizer, Australia) as a SC injection every 12 hours at a dose rate of 0.4 mg/kg for 3 days. In addition she was given SC injections of meloxicam (Metacam®, Boehringer Ingelheim, Australia) every 24 hours at a dose of 0.2 mg/kg for 7 days and a single intracoelomic injection of 3 ml of warmed sodium chloride solution.

In order to maintain Tatiana's hydration levels during hospitalisation she was soaked in clean, fresh water for 30 minutes each day between bandage changes. Because the shell fracture was located quite dorsally on her carapace it meant she could be put in 1–2 cms of clean water without risk of the water entering the coelomic cavity through the shell fracture.

Shell repair

Fourteen days after initial presentation Tatiana's shell fracture was assessed and determined to be ready to be stabilised.

There have been many different methods used to fixate shell fractures in turtles including glass ionomers (Fowler and Magelakis, 2003), cable ties (Forrester and Satta, 2004), plastic irrigation saddle clamps (Vella, 2009) and fibreglass plates (Kishimori, 2001). Given the size, shape and degree of depression of the shell fracture in this case it was elected to use a combination of stainless steel orthopaedic screws and wire.

Tatiana was anaesthetised with an intravenous (IV) injection of alfaxalone (Alfaxan®, Jurox, Australia) at a dose rate of 4 mg/kg (Figure 4). She was intubated with an 18 gauge intravenous catheter connected to 3 mm endotracheal tube fitting. This in turn was connected to a positive pressure ventilator delivering a breath every 15 seconds. She was maintained on 2% isoflurane (Isoflurane, Delvet, Australia) and oxygen.

The fracture site was prepared using a 0.05% chlorhexadine solution. A small pair of haemostats were used to lift the depressed fragment into a more natural position. Four 3.5 mm long stainless steel orthopaedic screws were placed in the shell around the fracture site (Figure 5). 22 gauge stainless steel wire was then secured around these screws to lift and stabilise the broken shell fragments (Figure 6).

Silver sulfadiazine was once again applied to the fracture lines. The entire area was then bandaged with a transparent, adhesive dressing (Opsite™, Smith & Nephew, Australia) (Figure 7). A single SC injection of meloxicam at a dose of 0.2 mg/kg was given.

Tatiana recovered uneventfully from her anaesthetic and was kept in hospital for a further 3 days for observation.

Post discharge

When Tatiana was discharged back to her owners they were instructed to change her bandage every 3 days for 1 month. She was to be kept inside during this time and allowed access to shallow water to drink and eat.

She was re-examined 1 month later. The shell fracture was healing very well. She had been eating and her weight was stable at 315 g.

At this time her owners were advised to stop further bandaging and allow her access to deeper water for 30 minutes a day for another month. They were to keep her inside over the winter period and bring her back in 3 months to have the screws removed.

In late September Tatiana received her final veterinary check (Figure 8). She had been swimming normally, was not showing any buoyancy issues and had been eating well. The stainless steel screws and wire were removed from the shell and she was released back to her outdoor enclosure (Figure 9). At the time of this publication she continues to do well.

Conclusion

Traumatic shell fractures in aquatic turtles can present a treatment challenge for veterinarians, particularly if the coelomic cavity is penetrated. Careful assessment of the injury needs to be made to determine the best course of action. Adequate decontami-nation of the wound, appropriate selection of antibiotic treatment and the provision of analgesia are all important. There are many methods that have been used to repair these types of injuries and the selection of any one particular method is based on the location and severity of the damage. Shell fractures take many months to heal but with time these animals can do very well.