This patient care report highlights the veterinary nursing interventions provided to a feline patient that presented to the practice in hypovolaemic shock.

Signalment

Species: Feline

Breed: British shorthair

Age: 4 years old

Sex: Malel(neutered)

Weight:l5.9 kg

Reason for admission/presenting clinical problem

This cat arrived at the surgery in a semi-collapsed state. The owner was suspicious of poisoning as the patient appeared unsteady and depressed. On examination it was quickly established that the patient had a dislocated hip and was suffering from shock, presumably following a road traffic accident.

Patient triage/major body systems assessment

The patient was triaged by assessing his cardiovascular, respiratory and neurological systems as detailed below:

Veterinary investigations and emergency database

Radiographs confirmed a dislocated hip and revealed an abdominal rupture (Figure 1).

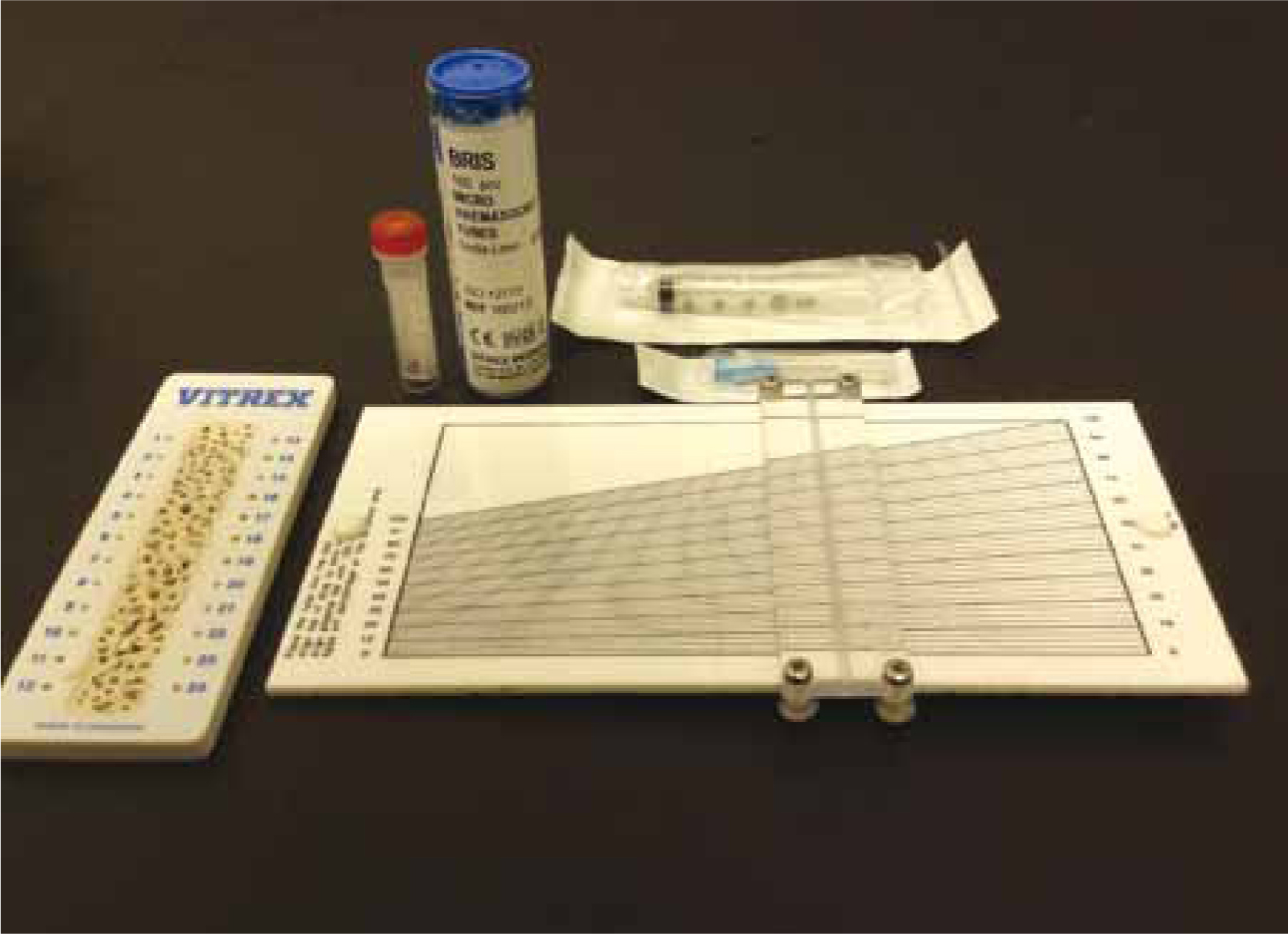

The patient had a packed cell volume (PCV) of 30% (reference range (RR) 27–50%), Total solids of 59 g/l (RR 54–78 g/l) (Figure 2). Blood was sent to the external laboratory for basic haematology and biochemistry as no in house facilities existed. A lactate measurement would have been valuable to gain more knowledge regarding the patient's perfusion status (Humm, 2008; Bilbrough, 2009) but Bilbrough (2009) advises there is no clinical benefit to measuring this parameter unless the results are available within minutes.

Initial management/veterinary interventions

The aim when treating hypovolaemic shock is to restore and maintain adequate circulating intravascular volume (Wemple, 2010; Humm, 2008). Various fluid therapy strategies can be used and there is little evidence in veterinary medicine to ascertain one particular method that is universally superior (Aldrich, 1999; Humm, 2008). The veterinary surgeon (VS) used Hartmanns, an isotonic crystalloid, at a rate of 49 ml/hour (four times maintenance). Slightly higher rates of 20 to 40 ml/kg (Aldrich, 1999), 10 to 30 ml/kg (Gurney, 2008) and a 10 ml/kg bolus (Higgins, 2009) have been suggested in other texts. Gurney (2008) and Higgins (2009) advocate the importance of assessing and evaluating the response to the fluid therapy and then adjusting the treatment plan as necessary; this is far preferable to using one rigid treatment plan for all animals. Colloids can also be used; these are much more efficient at expanding the intravascular volume and can be given at much lower volumes; Humm (2008) suggests a rate of 5 ml/kg.

The VS gave the patient an injection of buprenorphine (Vetergeric, Alstoe limited) on admission and repeated this after 6 hours. Higgins (2008) stressed the importance of using analgesia in cases of traumatic shock to reduce pain, which can cause vasoconstriction, reduced cardiac output, hyperventilation, reduced wound healing, increased circulating inflammatory cytokines, stress and fear.

Aims of intensive care

There are a number of aims of intensive care:

Discussion of nursing interventions

General monitoring of patient condition

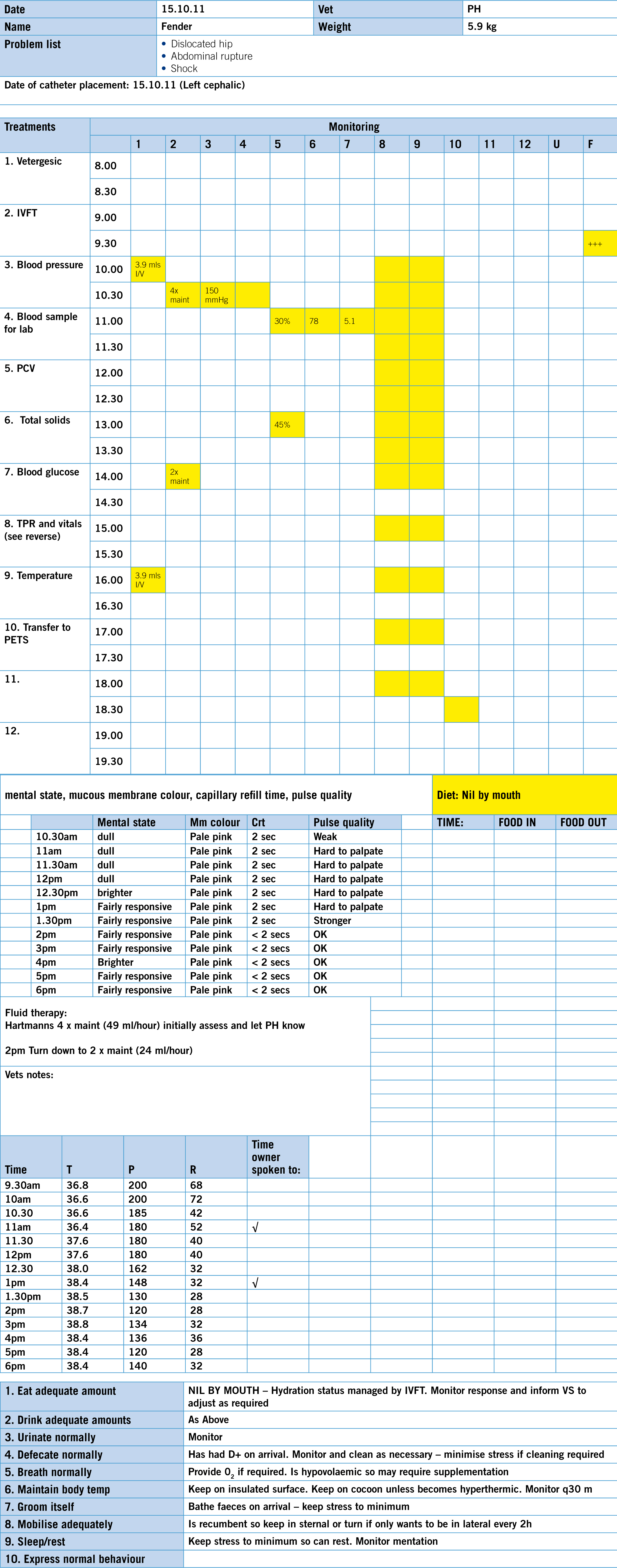

The veterinary nurse (VN) plays a vital role in monitoring the shocked patient. Early recognition of clinical signs relating to a change in condition can greatly impact the outcome of the patient (Wemple, 2010). As recommended by Higgins (2009) the patient's mental state, mucous membrane colour, capillary refill time, heart rate, blood pressure, pulse quality and temperature were measured and recorded every 30 to 60 minutes initially and documented on the hospitalisation form (Figure 3). These are all vital parameters that demonstrate the cardiovascular status and therefore the body's ability to provide adequate oxygen to the cells.

Arterial blood pressure is a measure of systemic vascular resistance and cardiac output (Aldrich, 1999; Clark, 2009) which can become compromised due to hypovolaemic shock. A blood pressure measurement was obtained in this patient using an indirect technique with a Doppler device and measured 150 mmHg.

The patient's respiratory rate and effort were monitored closely, particularly as he had suffered a traumatic impact and further complications of this may have developed. The patient seemed most comfortable in sternal recumbency which was ideal to support a normal lung function; however it was documented on his hospitalisation chart that if he was to lie in lateral recumbency then turning every 2 hours would be necessary to prevent atelectasis.

Hydration status

Although fluid choice and rate is the decision of the VS, the VN will be able to provide better care of the patient with an understanding of the processes that occur as a result of fluid therapy. The VN should possess the ability to recognise signs that indicate improvement, or conversely, recognise the patient's condition deteriorating. An initial assessment was made of the patient's heart rate, pulse quality, mucous membrane colour, capillary refill time and respiratory rate as recommended by Gurney (2008) who emphasises the importance of monitoring these parameters to gauge a response to the fluid therapy treatment. These parameters, as well as chest auscultation, were assessed on admission and then every 30 to 60 minutes. A sign of improvement would be normalisation of the above parameters (Higgins, 2009). A concern of fluid therapy, especially when given at high rates, as in this case, is over infusion. A crystalloid solution swiftly equilibrates with the interstitial space meaning interstitial oedema will be a result of over infusion; signs of limb oedema or pulmonary oedema highlighted by the patient coughing or ‘crackles’ heard on chest auscultation should be observed for (Steward, 2007).

The patient's PCV was measured as well as the total solids, as these are useful values to be able to measure patient response to fluid therapy (Gurney, 2008).

Other useful methods of monitoring hydration status endorsed by Clark (2009) and Gurney (2008) are measuring urinary output and urine specific gravity by means of urinary catheterisation and central venous pressure using a central catheter.

Control of temperature

Peripheral vasoconstriction occurs in hypovolaemic shock as the body compensates to protect the vital organs; the body temperature is likely to decrease as a result of this mechanism and it is vital the VN monitors and acts accordingly (Wemple, 2010). The patient's rectal temperature on admission was 36.8°C; by using a patient care plan and applying the knowledge that hypothermia was likely to occur, preventative measures were put into place. Dix et al (2006) define hypothermia as a sub-normal body temperature relating to core temperatures between 32–37°C. They describe the general depressant effect that occurs with potential detrimental consequences, especially in an already compromised patient that has impaired heat production and conservation mechanisms. The metabolic rate decreases by approximately 10% for each 1°C drop in core temperature (Hobbs, 2002). The cardiovascular system is affected as bradycardia and a reduction in cardiac output subsequently cause a decline in arterial blood pressure. The risk of cardiac arrhythmias is greater as the electrical conduction of the heart is affected. Blood clotting times rise due to decreased activity of clotting factors and blood viscosity may also increase, which heightens the risk of clotting. Shivering increases oxygen requirements, decreases effective ventilation and increases pain levels (Clark, 2003; Dix et al, 2006; Archer, 2007; Lamb, 2009). Wemple (2010) and Gurney (2008) describe bradycardia as a common result of hypovolaemic shock in felines and so this was already a concern in this case.

To reduce heat loss and aid re-warming the patient was placed on a towel and enclosed in a recovery warm air blanket attached to a ‘cocoon’ heater (AAS Darvell, USA) (Figure 4). Warm air blankets provide indirect active warming and were shown to minimise hypothermia in anaesthetised cats in a study carried out by Machon et al (1999). Archer (2007) and Clark (2003) describe this as a preferable method to achieve active warming compared with direct heat provided by electric heat pads, hot water bottles or ‘hot hands’ (latex gloves filled with warm water), as thermal burns are possible especially in the recumbent patient. The towel underneath the patient acted as an insulation layer to prevent heat loss via conduction. Lamb (2009) describes other methods of insulation such as bubble wrap, material or foil blankets which she advises can reduce heat loss by 30%. Pre-warmed intravenous fluids were used to encourage active core warming. A study carried out by Dix et al (2006) highlighted the importance of actively maintaining the temperature of the fluids rather than just pre-warming them due to the heat loss that occurs as the fluid travels down the giving set. The most effective results were achieved by pre-warming the fluids and the giving set to 38°C, using a fluid heat retention bag over the bag itself and wrapping 30 cm of a distal portion of the giving set around ‘hot hands’. These measures were not undertaken in this case meaning that the cooling fluids may have affected the ability to maintain normothermia in the patient. The temperature was measured rectally every 30 to 60 minutes until the patient was normothermic. Rectal temperature is not a measurement of the core temperature but Archer (2007) endorses it as a simple way to obtain and measure trends. Measuring rectal temperature against the temperature found between the digits can be a good indicator of peripheral perfusion; Leece and Hill (2003) report the normal difference to be approximately 3°C but this would be expected to be greater in cases of hypoperfusion. Using the methods described above and with the knowledge obtained by constant monitoring, the patient's temperature returned to normal and was able to be maintained for the remainder of his stay.

Patient outcome

Using the methods described above the patient remained stable throughout the day and was able to be transferred for further investigations and care at the out of hours providers where he stayed for ongoing stabilisation and assisted feeding for four days. Following this he returned to the practice for a femoral head and neck excision and abdominal rupture repair.

Conclusion

Even in a practice with limited equipment there are basic techniques that can be applied to patients in hypovolaemic shock by the VN with very effective results. Monitoring the shocked patient is crucial, however, having an understanding of the physiology behind the signs will vastly influence patient outcome as the VN is able to notice and act on signs quickly and effectively (Aldrich, 1999).