The American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM) has just published a consensus statement, providing guidelines for veterinary surgeons to help them manage cases of feline cardiomyopathy (Luis Fuentes et al, 2020). This is great news for veterinary nurses as well, because nursing recommendations have also been included. The guidelines acknowledge that it has been challenging for veterinary surgeons to define and classify feline heart disease, especially when they are frequently presented with a dyspnoeic and/or uncooperative cat. It also accepts that if there is no trained cardiologist available, then skilled techniques such as echocardiography can prove difficult. The new guidelines have changed the way that the disease is classified, but importantly also puts emphasis on a new staging system which can help guide treatment, changing focus to a more practical and clinical approach of the patient. The ACVIM Consensus Statement can be read in full here: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jvim.15745.

Why was a Consensus Statement Needed?

Cardiomyopathy is the main cause of cardiac morbidity and mortality in cats, and hyper-trophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is the most commonly diagnosed form (Payne et al, 2015). Cats can often have asymptomatic (occult) heart disease for years, and only present when severe signs occur, such as congestive heart failure (CHF) or aortic thromboembolism (ATE), both of which are related to a poor prognosis. Furthermore, as reported in humans, cats with HCM can die suddenly. One necropsy study showed that in a referred population of cats, 15% of cats with HCM died suddenly (Wilkie et al, 2015). Table 1 outlines some of the difficulties acknowledged by the ACVIM consensus statement using current methods to diagnose a cat with heart disease.

Table 1 Challenges faced by veterinary surgeons when diagnosing cats with heart disease

| Diagnostic test | Problems |

|---|---|

| Auscultation | Murmur is an unreliable indicator of heart disease. Some cats can have no murmur and have heart disease present, while some may have a murmur and no heart disease |

| Radiography |

|

| Electrocardiography (ECG) | Insensitive for heart disease |

| Echocardiography — general |

|

| Echocardiography — technical challenges |

|

| Biomarkers |

|

Connolly et al, 2009; Wagner et al, 2010; Borgeat et al, 2014a; Wells et al, 2014; Borgeat et al, 2015; Fox and Schober, 2015; Luis Fuentes et al, 2020

New Disease Definitions — What has Changed?

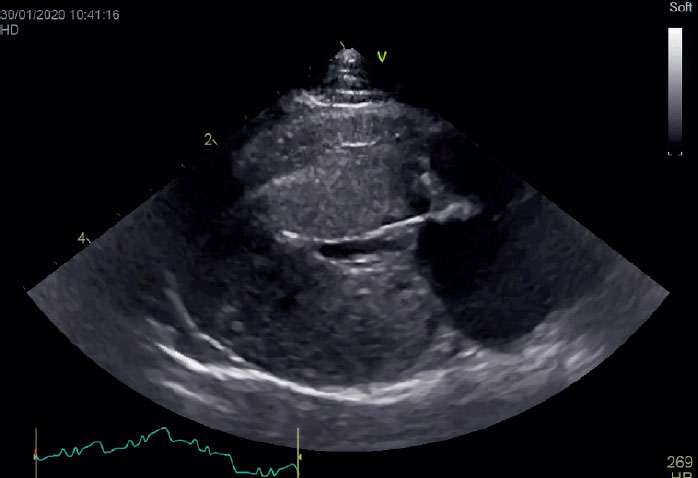

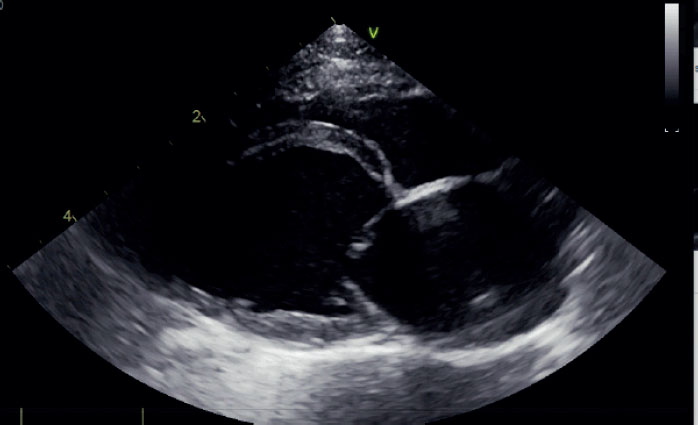

The new approach of defining feline cardiomyopathy is based on phenotypical features rather than the underlying cause, which as shown in Table 1, can be difficult. Cardiomyopathies are a diverse group of myocardial diseases with varied phenotypes and prognosis. A phenotypical trait is an obvious, observable, and measurable trait. Figures 1 and 2 show examples of two different phenotypes that nurses may be familiar with, HCM and restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM). The images show the obvious differences in appearance. The guide-line classification changes also allow for an explanation of cardiac changes, but do not make assumptions about the underlying cause. For example, the heart can look like it has a thick ventricle (for example, it looks like HCM), but the diagnosis does not have to be one of HCM. The reason this is important is because there can be other causes of left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy that can give an appearance of HCM to the LV, such as aortic stenosis, hypertension, hyperthyroidism or acromegaly (Luis Fuentes et al, 2020). The hypertrophic phenotype appears to predominate in cats with subclinical cardiomyopathy, but the prevalence of other cardiomyopathy phenotypes is not known (Luis Fuentes et al, 2020). As before, to receive a diagnosis of HCM, the LV must be thickened.

The consensus statement was adapted from the human classification system of the European Society of Cardiology (Elliott et al, 2008). Five phenotypic categories have been identified for use in cats, which are detailed in Table 2. These descriptions are based on echocardio-graphic findings.

Table 2 Description of phenotypic groups

| Phenotype | Definition |

|---|---|

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) | Diffuse or regional increased left ventricular (LV) wall thickness |

| Restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM) | Normal LV dimensions with left atrial or biatrial enlargement |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) | LV systolic dysfunction, characterised by progressive ventricular dimensions, normal or dilated LV wall thickness and atrial dilatation |

| Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (ARVC) | Severe right atrial and right ventricular dilatation. Arrhythmias and right sided congestive heart failure common |

| Nonspecific phenotype | A cardiomyopathic phenotype that is not satisfactorily explained by the other groups. |

Adapted from Luis Fuentes et al, 2020: 1064

It is to be noted that the phenotypic group can change over time, either due to disease progression, concurrent disease processes such as hypertension or hyperthyroidism, or for reasons not yet understood.

Staging System

The new staging system for feline heart disease is based on a combination of classification systems — the human-based American Heart Association system (Hunt et al, 2005), and the ACVIM system used in dogs with myxomatous mitral valve disease (Atkins et al, 2009 and updated by Keene et al, 2019). A summary of the feline classification system is listed in Table 3.

Table 3 The feline classification system as published by the ACVIM Consensus Statement (Luis Fuentes et al, 2020)

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| A | Cats that are at risk of, or are predisposed to, developing cardiomyopathy but currently have no evidence of disease |

| B | Cats in this group have been diagnosed with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) (because they have increased left ventricular (LV) wall thickness) but have no clinical signs. This group is divided in to two separate categories:

|

| C | Cats that currently have, or have had, signs of CHF or ATE |

| D | Cats that have become refractory to conventional CHF treatment |

Recommendations for Diagnosis

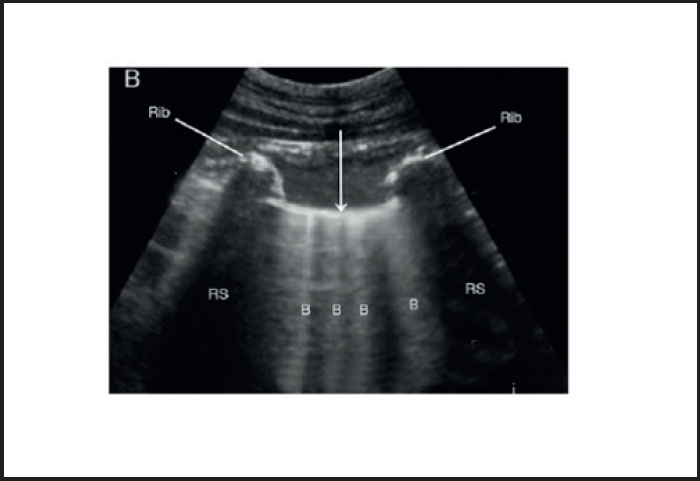

The ACVIM consensus statement also makes recommendations on diagnostic techniques. Genetic testing is still recommended for Maine Coons and Ragdolls that are being considered for breeding, as genetic mutations have been found in these breeds (Meurs, 2005; 2007), but the statement makes clear the limitations that exist with this test, emphasising the value of physical examination and echocardiography for stage A cats. Recommendations for physical examination remain much the same, with emphasis on the fact that some cats will have disease present but have no auscultatory changes. It states that certain prognostic indicators, such as a gallop rhythm or arrythmias, are more likely to be associated with cardiomyopathy. Echocardiography is still considered the gold standard method of cardiomyopathy diagnosis, although the guidelines acknowledge the difficulty in achieving gold standard measurements. Instead, it recommends for the unstable patient, and/or if no specialist is available, to perform a ‘focused point-of-care’ examination, or lung ultrasound at the kennel, using ultrasound to assess for abnormal fluid accumulation, such as pulmonary oedema with the presence of B lines (Figure 3), or pleural or pericardial effusions. It can also be used to estimate left atrial (LA) size and LV systolic function.

It is now suggested to monitor thyroxine levels in cats over the age of 6, if they have ausculta-tory abnormalities, even if there is no suggestion of concurrent LV hypertrophy. Hypertension is a common finding in cats, and it is advised that any cat with increased LV wall thickness, should have blood pressure measured.

Treatment and Nursing Recommendations

A brief overview of the treatment and nursing guidelines is listed in Table 4.

Table 4 Treatment and nursing guidelines proposed in the new consensus statement

| Stage | Treatment guideline | Nursing recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| A | No treatment recommended. Suggested that queens of high-risk breeds are assessed regularly by a cardiologist. Genetic tests performed where applicable | None |

| B1 | No treatment recommended. For cases diagnosed with severe left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (LVOTO), atenolol may be used if it can be given consistently | Annual screening recommended to owners |

| B2 | Clopidogrel recommended for cats at risk of developing aortic thromboembolism (ATE). Suggested indications are moderate to severe left atrial (LA) enlargement, low LA fractional shortening, low LA appendage velocities and the presence of spontaneous echo contrast.Other anti-thrombotics may also be considered in cats at high risk.Progression of disease should be monitored, but weighed against the risk of stress to the cat.For cats with ventricular ectopy, treatment with atenolol or sotalol may be recommended | Owners to monitor resting respiratory rate |

| C | Acute decompensated failure.Diuresis, oxygen, sedation if necessary, thoracocentesis if appropriate.In cases presenting with low cardiac output, consider pimobendan if no obvious LVOTO. If no improvement with pimobendan, consider continuous rate infusion of dobutamine.It is recommended to send the patient home as soon as it has been stabilised.Re-examination recommended 3–7 days later to check for the resolution of congestive heart failure (CHF), renal function and electrolytes | Acute decompensated failure. Minimise stress, provide oxygen, and prepare thoracocentesis equipment as required.Monitor blood pressure, respiratory rate, bodyweight, body temperature and estimated urine output.Owner to monitor respiratory rate at home. Therapeutic goal to maintain rate to under 30 breaths/minute at home |

| Chronic heart failureFurosemide — after initiation of furosemide, examine in 3–7 days to check renal and electrolyte parameters.Clopidogrel — recommended for any cat with moderate to severe LA enlargement. Pimobendan — recommended in cats with no significant LVOTO.Re-examination in 2–4 months, but level of stress to the cat should be considered. Presence of concurrent disease may warrant more frequent checks | Owner to monitor respiratory rate at home. Therapeutic goal to maintain rate to under 30 breaths/minute at home | |

| D | Torasemide is recommended if the patient has become refractory to furosemide.Spironolactone may be added to aid diuresis.Pimobendan may also be added, if not already included.Potassium or taurine supplementation as indicated.N.B. Owner/cat compliance need to be considered when adding additional medication | High salt foods are to be avoided, unless cardiac cachexia is a concern. If this is the case, calorie intake should be prioritised. Regular body condition scoring and bodyweight should be recorded |

Management of Aortic Thromboembolism

Euthanasia is still the most common outcome for an ATE in general practice (Borgeat et al, 2014b). The ACVIM statement outlines that poor prognostic indicators include hypothermia, more than one limb effected, and the presence of CHF. However, if treatment is to be initiated, effective pain management is crucial, especially within the first 24 hours. It is recommended that analgesics such as fentanyl or methadone are used. Until the cat has been stabilised and can be given oral medication, either a low molecular weight heparin, unfractionated heparin, or an oral Xa inhibitor (such as rivaroxaban) should be administered. Clopidogrel is recommended as soon as oral medication is tolerated. Post ATE management recommendations are that the patient be re-examined 3–7 days after discharge, and regular checks post event to monitor for necrosis, electrolyte imbalance, appetite and treatment compliance, as well as for neuromuscular improvement. However, this needs to be assessed in conjunction with the additional anticipated stress to the cat. Resting respiratory rate should be monitored at home.

Conclusion

The new ACVIM guidelines have provided some much needed clarity and recommendations for those veterinary professionals managing cats with cardiomyopathies. The nursing guidelines can help nurses understand cardiomyopathies, be aware of treatment aims, and provide a frame of reference to help their own practice, based on the best of current thinking. The fact that these guidelines are free to access means that they can be a vital addition to any veterinary setting.

Key Points

- A consensus statement has been released, providing guidance on the classification, diagnosis, and management of cardiomyopathies in cats.

- The guidelines are for veterinary surgeons and veterinary nurses.

- The consensus statement is open access, allowing everyone to have a copy without cost.

- The statement gives an easy to use staging system to help guide treatment and nursing.