Acromegaly is the term used in human medicine to describe a condition resulting from chronic excessive growth hormone (GH) secretion. The word acromegaly derives from the Greek noun ‘akros’ meaning extremity and affix ‘megaly’ meaning abnormal enlargement. Acromegaly can result in gigantism in humans if the condition occurs before growth plate closure, however it is most commonly diagnosed in middle-aged and older humans when it results in increased soft tissue and bone growth without gigantism. The term hypersomatotropism (HST) rather than acromegaly may be appropriate when describing the condition resulting from chronic excessive GH secretion in cats because growth hormone-induced enlargement is more difficult to identify in adult cats.

The first description of HST in cats was in 1976 (Gembardt and Loppnow, 1976). The estimated prevalence of diabetes mellitus (DM) in the insured UK cat population was 1 in 230 cats in 2003 and feline HST appears to be the cause of DM in up to 25% of diabetic cats (McCann et al, 2007; Schäfer et al, 2014; Niessen et al, 2015). However, feline HST is considered to be an underdiagnosed endocrine disorder in the UK which was highlighted by the results of one study which reported three quarters of veterinarians did not suspect HST when cats were highly likely to be affected by the condition (Niessen et al, 2015).

Pathophysiology

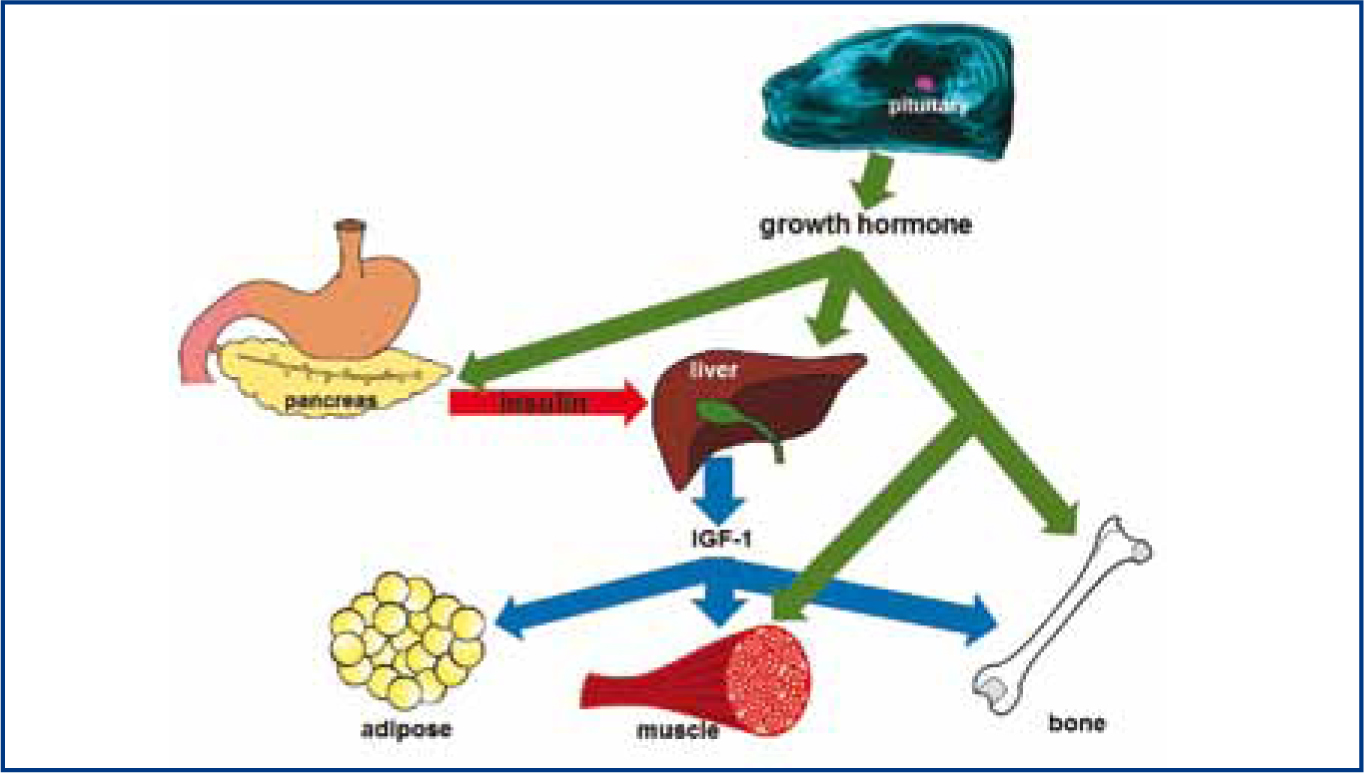

The pituitary gland is an endocrine organ at the base of the brain (Figure 1a and 1b). This gland secretes several hormones, including GH, which are required for effective homeostasis. Feline HST is caused by a functional GH secreting pituitary tumour. Unlike many hormones which act on a specific target gland, GH affects almost all tissues in the body either directly or indirectly by increasing the secretion of a hormone from the liver known as insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1). The main anabolic effects of GH and IGF-1 are enhanced protein synthesis and bone growth resulting in increased bodyweight. The main catabolic effect is increased mobilisation of fat from adipose tissue for use in energy production, resulting in overall lower body fat (Figure 2). However, it is the antagonistic action of GH on insulin that causes many of clinical signs of HST in cats. Almost all cats with a diagnosis of HST have concurrent DM because the ability of insulin to promote glucose uptake into tissues is reduced in the presence of excessive of GH. The end result of chronic GH-induced insulin antagonism is hyperglycaemia and secondary glucosuria, i.e. DM.

Clinical aspects of HST

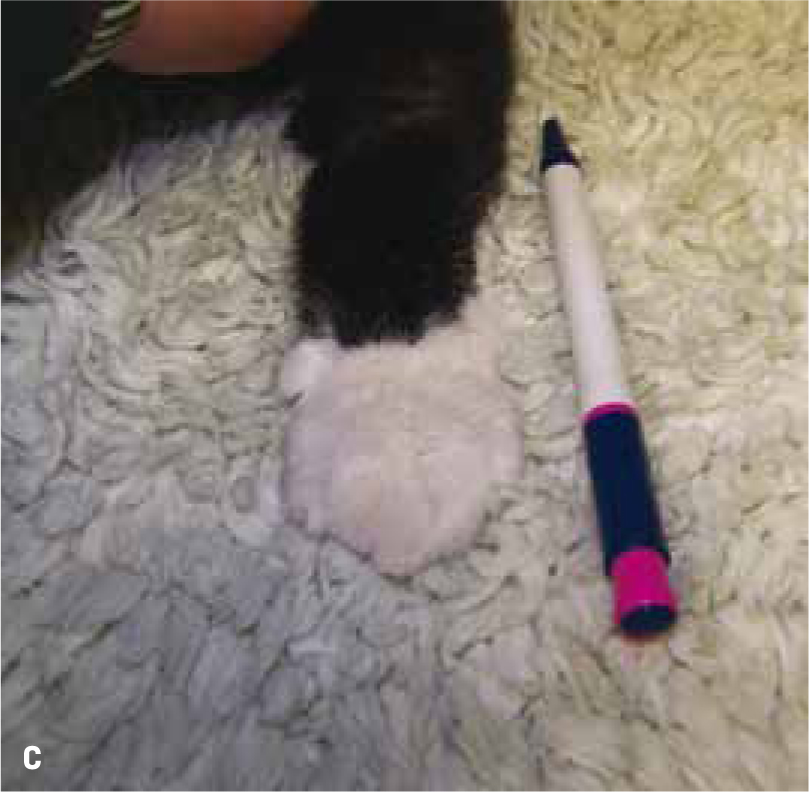

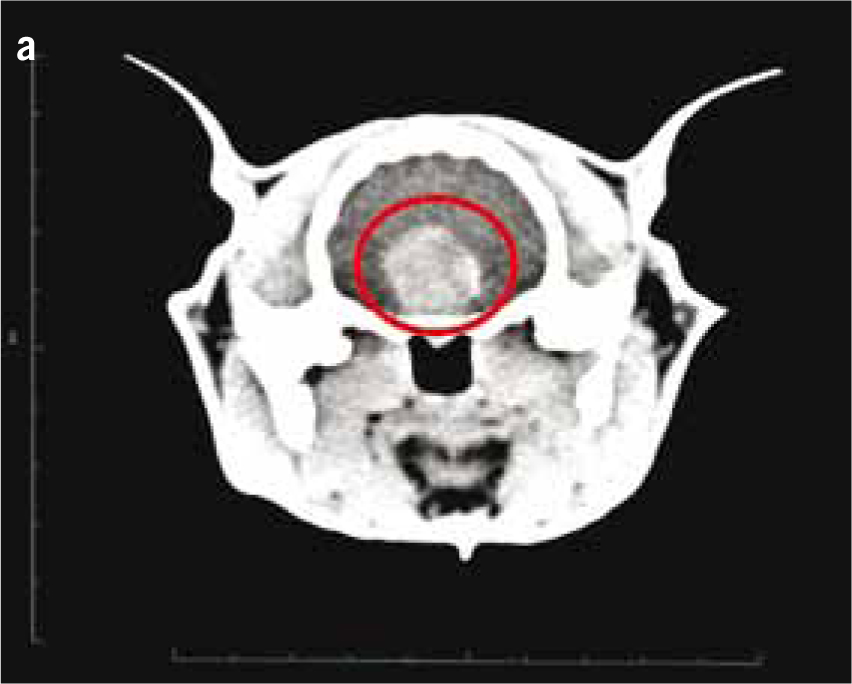

Non-HST cats that develop DM are thought to do so because of a combination of environmental (diet, body condition, level of activity) and genetic pressures on pancreatic endocrine function, with an end result of hyperglycaemia. DM in these patients is typically controlled with insulin doses less than 1.5 units/kg/day (Niessen et al, 2010; Sparkes et al, 2015). However, HST-induced DM cats may require much higher insulin doses due to marked insulin resistance, with early reports of up to 130 units of insulin being used per day in an attempt to manage the DM of these cats (Lichtensteiger et al, 1986; Peterson et al, 1990). These patients in earlier studies represent severe cases of HST. It is now recognised that there is a spectrum of disease severity, and that those HST DM cats diagnosed early in the disease may not require high insulin doses. Nevertheless, the most common clinical signs of HST are those associated with uncontrolled DM such as polyuria, polydipsia and polyphagia, but unlike routine poorly controlled diabetics, HST cats often continue to maintain or gain weight. Other common clinical signs occur as a consequence of adult onset tissue growth such as snoring, abdominal enlargement secondary to organomegaly, increased spaces between teeth, broad facial features, development of an overshot jaw and enlargement of feet or ‘clubbed paws’ (Figure 3) (Niessen et al, 2007a). There can be enlargement of the soft tissues around joints and degenerative joint disease which contribute to osteoarthritis. A minority of cats will exhibit neurological signs such as cranial nerve deficits, circling, confusion and depressed mentation due to brain compression if the pituitary tumour is very large (Figure 4a and 4b).

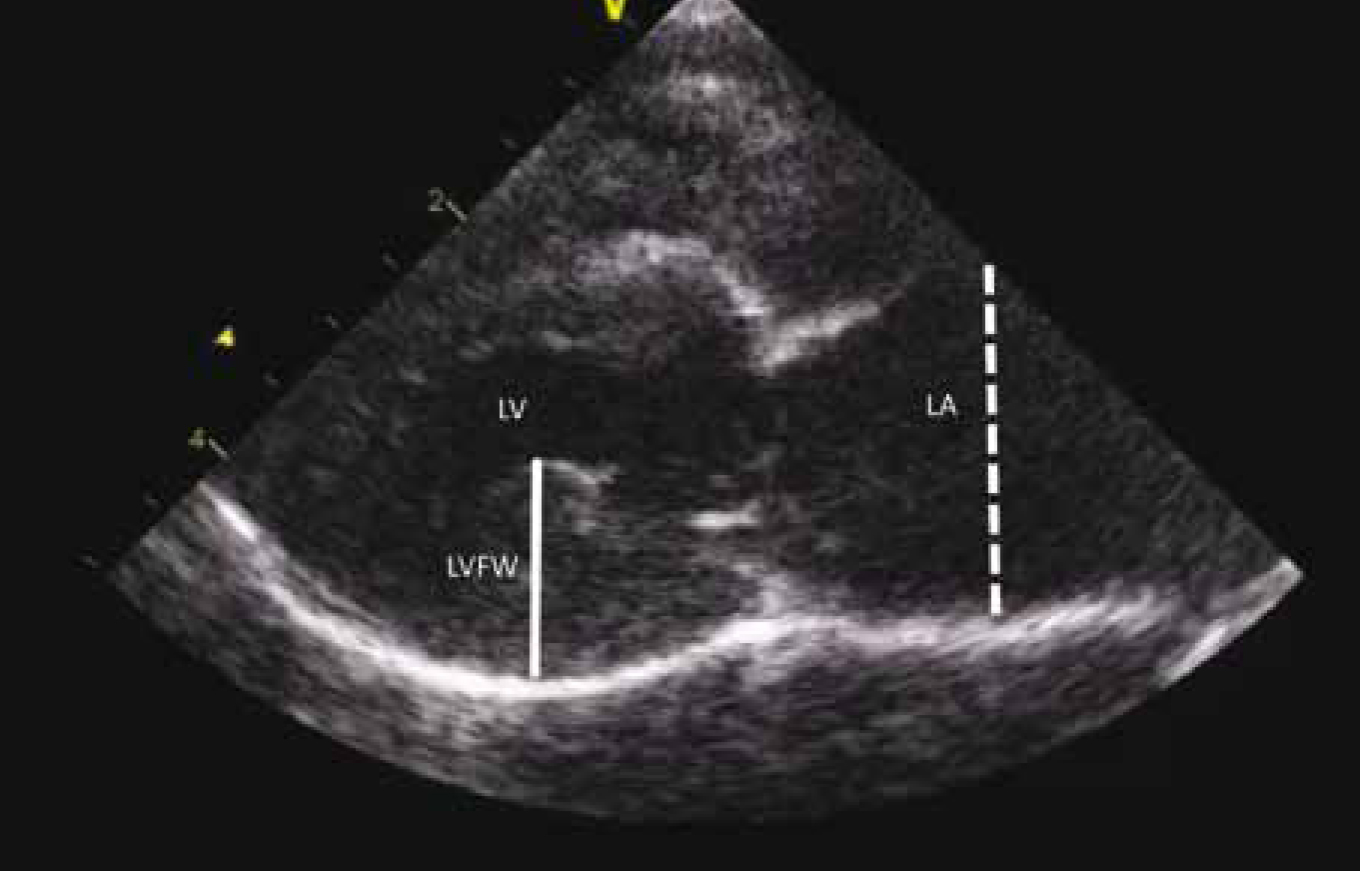

Abdominal ultrasound may reveal enlargement of the kidneys, adrenal glands and pancreas in HST cats, however some of these findings may be just attributable to the fact that HST cats are larger and have a heavier bodyweight than unaffected cats rather than disproportionate organ enlargement (Lourenço et al, 2015). Echocardiography commonly reveals enlargement of the ventricular walls with the heart having the appearance of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and HST increases the risk of congestive heart failure in cats (Figure 5).

Routine laboratory and diagnostic tests

Most HST DM cats have slight anaemia and higher serum fructosamine than non-HST DM cats (unpublished work). However, despite HST DM cats typically being more difficult to control diabetics, there are no routine blood or urine tests that are highly suggestive of HST. Specific endocrine tests are required if a diagnosis of HST is to be made.

One option is to measure blood levels of GH. HST cats have higher levels of circulating GH than unaffected cats, however this test is not currently commercially available in the UK (Niessen et al, 2007b). An alternative option is to measure IGF-1. GH induces IGF-1 secretion from the liver in the presence of insulin. Excessive GH increases IGF-1, and as the half-life of IGF-1 is much longer than GH (several hours vs several minutes), IGF-1 represents an indirect measurement of GH. There is a commercially available IGF-1 assay that has been validated for cats (Niessen et al, 2007a), and practices can send off blood samples for analysis (http://www.rvc.ac.uk/Media/Default/Pathology%20and%20Diagnostic%20Laboratories/Documents/RVC%20Di-abetic%20profile%20-%20limited%20for%20RVC%20webpage.pdf). Most non-HST cats will have an IGF-1 result between 200 and 700 ng/ml. A cat with an IGF-1 result greater than 1000 ng/ml has a 95% probability of having HST (Niessen et al, 2015). A proportion of HST cats will have an IGF-1 within the normal range at the time of diagnosis of diabetes. Most newly diagnosed diabetic cats have a low or low normal baseline and stimulated insulin levels (Nelson et al, 1999) and this may affect the liver's ability to produce IGF-1. This ‘false low’ is likely to be caused by the liver being exposed to GH but insufficient insulin — the liver needs sufficient insulin and GH exposure to secrete IGF-1. Therefore, if there are financial limitations, it might be prudent to treat a newly diagnosed diabetic cat with insulin for at least 6–8 weeks before measuring IGF-1.

There are a number of cats that will have IGF-1 levels >1000 ng/ml (around 5% of diabetic cats) that do not have HST (Niessen et al, 2015). Therefore determining if a patient truly has HST is an important next step. The current non-invasive test of choice is to per form intra-cranial imaging to assess the size of the pituitary (Niessen et al, 2015). The vast majority of HST cats have pituitary enlargement (pituitary height >4 mm) while incidental pituitary enlargement in older cats is uncommon (less than 2%) (Lamb et al, 2014; Niessen et al, 2015). Intra-cranial imaging can be performed using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) (Posch et al, 2011; Lamb et al, 2014). Cats with an IGF-1 > 1000 ng/ml and pituitary enlargement are currently considered to be affected by HST.

Treatment

There are currently limited options for the medical management of HST. One option is to not treat the HST directly but attempt to manage the resultant DM. This may be effective in the early stages of disease when insulin resistance is mild and allow temporary good control, and in some cases even temporary remission of DM. It is important to have compliant owners and good veterinary team–owner communication if this treatment option is used. It has been reported that the care of diabetic humans is better when a nurse-led diabetic clinic is available, and a veterinary nurse-led diabetic clinic would be useful to achieve the level of communication required to manage the difficult to control HST DM cat (Ohman-Strickland, 2008). Owners of HST DM cats should be informed that their cat can have a variable day-to-day response to exogenous insulin. This variable response to insulin could result in iatrogenic hypoglycaemia on an insulin sensitive day. Clinical signs of hypoglycaemia in cats can initially be subtle, such as lethargy, weakness and vocalisation, but may progress to tremors, ataxia and latterly seizures and coma if hypoglycaemia is not corrected. Owners should be able to identify these events and preferably confirm using a home blood glucose test, able to manage these events at home in an emergency situation and then contact their veterinary practice for further advice. The authors typically recommend giving a rapidly acting oral source of carbohydrate such as GlucoGel© (BBI Healthcare, Bridgend, UK) or honey as viscous products are preferable rather than liquids (i.e. sugar dissolved in water) because some cats will have an altered mentation which may increase the risk of aspiration if administered an oral liquid. Cats should then be fed normal food if their mentation is appropriate or taken immediately to a veterinary practice if their mentation remains abnormal. The reason for giving a rapidly acting source of carbohydrate is to resolve hypoglycaemia as quickly as possible, and food is to sustain normoglycaemia. Owners should not give another dose of insulin without seeking advice. Many HST DM cats require gradually increasing doses of insulin over time due to increasing insulin resistance and persistently poor diabetic control. The insulin dose adjustments should be made using a combination of measures of glycaemic control such as clinical signs, blood glucose curves and fructosamine measurements. Blood glucose curves should be performed in a manner which is as welfare friendly as possible. The authors typically request that owners perform these curves at home by collecting seven blood glucose values over the course of 12 hours. The first glucose reading is obtained at the time of morning insulin injection and measurements every 2 hours up to and including the time of evening insulin injection. These measurements can be increased to hourly measurements if there is risk of hypoglycaemia, i.e. owners could be asked to perform hourly blood glucose measurement if the blood glucose goes below 7 mmol/litre and revert back to measurements every 2 hours when blood glucose has increased >7 mmol/litre. The authors typically collect blood samples from the marginal ear vein after trimming the hair over the vein, applying local anaesthetic cream (i.e. EMLA cream) and waiting for 45 minutes. This local anaesthetic cream can be applied every 4 to 6 hours as required, the effect lasting for 2 hours. A thin layer of petroleum jelly can be applied over the sampling site at the time of sampling and a spring loaded lancet or insulin needle used to puncture the vein and collect the sample followed by pressure applied to the venepuncture site. A veterinary calibrated glucometer is preferable to human calibrated glucometer.

Despite attempts to achieve good glycaemic control with insulin therapy alone, the long-term prognosis for most HST cats in terms of diabetic control is poor. This option does not consistently control polyphagia which can be extreme in some patients with some patients developing food aggression of meal times. The authors have trialled several different medications in an attempt to manage the polyphagia of affected patients but have not observed appetite suppression as yet.

In human medicine there are two main types of medication that be used to manage HST: GH antagonist drugs that prevent GH from binding to its receptor (e.g. pegvisomant) and drugs like somatostatin or dopamine agonists that inhibit GH secretion from the pituitary gland (Katznelson et al, 2014). To date the only drug to effectively reduce IGF-1 levels in HST cats is the somatostatin analogue, pasireotide (Scudder et al, 2015). This drug is sold as a short-acting product requiring twice daily subcutaneous administration, or a long-acting product requiring one monthly subcutaneous injection. The current limiting factor for the use of this drug in cats appears to be cost.

Pituitary radiotherapy can improve diabetic control in HST cats and is particularly useful at improving neurological signs that occur as a consequence of very large pituitary tumours that compress the surrounding brain (Littler et al, 2006; Mayer et al, 2006; Dunning et al, 2009). One major disadvantage of this treatment is radiotherapy is often given in five to 10 doses, known as fractions, over 2 to 3 weeks and on each occasion the cat needs to undergo general anaesthesia to safely receive each fraction. Additionally, the time to respond to this therapy is variable and those that do respond may relapse months later. A newer technique known as radiosurgery, a method of applying a large dose of concentrated high energy radiation to a specific tissue given in one or two doses, has recently been reported to successfully treat cat pituitary tumours, though similar long-term disadvantages apply (Sellon et al, 2009).

The treatment of choice in humans affected by HST is surgical removal of the pituitary tumour via a procedure known as hypophysectomy. This procedure was first described in dogs in 1886 and early reports of this procedure in cats date back to the 1970s when used to train human surgeons in microsurgical techniques (Snvckers, 1975). The first hypophysectomy to successfully treat HST in a cat was described in 2010, and a more recent report described 21 HST cats undergoing therapeutic hypophysectomy (Meij et al, 2010; Kenny et al, 2015). This procedure had a high success rate of curing HST and nearly 80% of cats surviving the procedure achieved diabetic remission. Those that remained diabetic experienced an improvement in their diabetic control and required lower doses of insulin to control their diabetes. As previously discussed, many HST cats have an increased risk of congestive heart failure and following successful hypophysectomy their heart function improves and the risk of congestive heart failure decreases (Borgeat, 2015). The survival rate of this procedure was 85% in the report published in 2015. One of the main differences of hypophysectomy in humans and cats is that human neurosurgeons aim to remove the pituitary tumour only (adenomectomy) while the pituitary is removed completely in cats. Therefore cats develop hypoadrenocorticism and hypothyroidism post operatively (due to loss of the anterior pituitary hormones adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH)) and require lifelong hormone supplementation. Arginine vasopressin (AVP) secretion from the posterior pituitary is disrupted post operatively and cats require AVP supplementation (e.g. desmopressin acetate, DDAVP, Ferring Pharmaceuticals) following surgery with most being able to discontinue this treatment within 2 months as their own natural AVP secretion normalises. The management of hypothyroidism and hypoadrenocorticism in cats is easier and provides better quality of life than persistently poorly controlled diabetes mellitus and HST. The immediate post-operative management of cats that have undergone hypophysectomy is complex and requires a multidisciplinary approach. Cats are typically hospitalised for 5 to 10 days in the post-operative period. Despite the challenges of the surgery itself and management of cats that have undergone hypophysectomy, this is the only intervention to date that has provided a long-term resolution of HST and diabetes in a large group of cats.

Conclusion

HST in cats occurs more commonly than previously recognised with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 800 to 1 in 1000 cats. HST causes diabetes mellitus in cats that is typically challenging to control and may require high doses of insulin. Other consequences of HST include increased risk of congestive heart failure, arthritis, increased upper airway soft tissue and neurological disease. There are currently limited medical options to treat this condition in cats, with pasireotide showing great promise to manage the disease and hypophysectomy being the only currently available option to cure HST.

Key Points

Conflict of interest: none.