References

An overview of decision making in veterinary nursing

Abstract

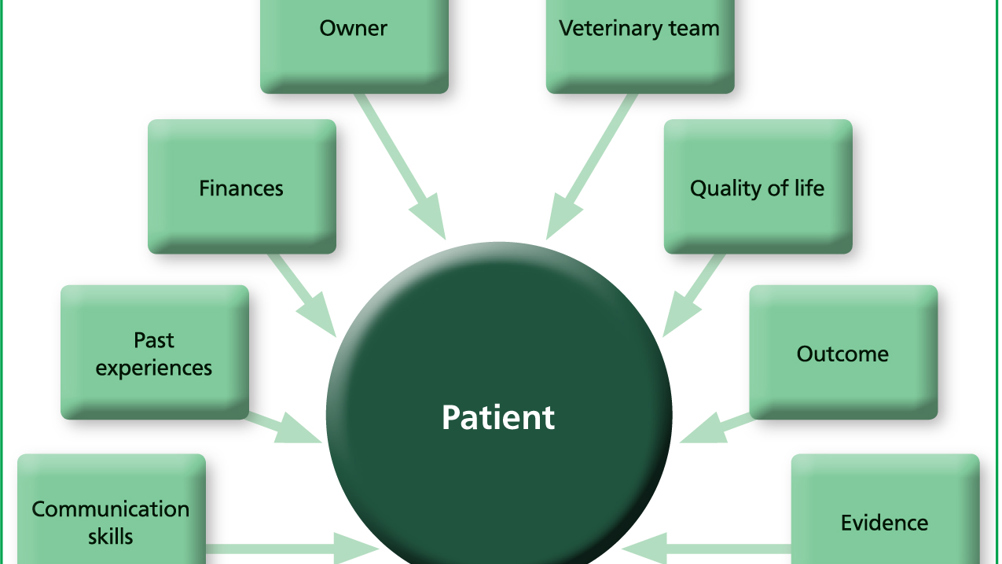

Decision making takes place in all aspects of veterinary care. Throughout any consultation, work up, hospitalisation or ongoing home care, decisions need to be made about the next step to be taken. Clinical decision making is influenced by many different factors including past experience, emotions, owner wishes, financial concerns and communication skills. Within the veterinary team, it is important that everyone understands the factors influencing decisions. Decision making can follow a paternalistic, guardian or shared approach, which tends to be dominant in veterinary practice. Where practices adopt standard operating procedures, the use of clinical evidence and clear non-biased decisions need to be made.

Making decisions is something that everyone does all day, every day: what to wear when going out, how to travel when going on holiday or what to have for lunch all require decision making. Decisions are also made in practice, but involve owners, opinions of colleagues and clinical evidence. Some decisions will be made instantly; others may take more time. In both situations, it is important to understand how those decisions are made.

When working with patients, you are continuously deciding on how to treat and care for them. You need to consider the clinical presentation, the way they respond to treatment, the evidence base, practice protocols, possible side effects and costs — to name a few factors — but it is important to stop and think about how you make those decisions. Clinical decisions may be based on practice protocol, the latest evidence, or personal experience. Where protocols or standard operating procedures (SOPs) are implemented, there needs to be an awareness of how these were developed. There needs to be an awareness amongst the end users of the decision making process that was applied to develop those protocols. Clarity and transparency of the methodology, training for the people sitting on such review panels and any conflicts of interest need to be acknowledged to ensure that all decisions are based on valid, reliable and current information.

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting The Veterinary Nurse and reading some of our peer-reviewed content for veterinary professionals. To continue reading this article, please register today.