Veterinary oncology is a rapidly growing field with cancer being such a common diagnosis in small animal practice and owners increasingly willing to choose treatment for their pets. The goal of treatment is to achieve as good a quality of life as possible, for as long as possible, rather than to achieve a cure. With this goal in mind, outcomes can be good as diagnostic and treatment options continue to improve and become more widely available. Where definitive treatment is not an option, palliative treatment is available and can make the animal comfortable during the latter part of life. This is the second in a series of articles aimed to provide information for veterinary nurses (VN) involved in the care of companion animal cancer patients. The first article focused on the pre-treatment phase of care — diagnosis and staging. The aim of this article is to describe the various cancer therapies available, focusing on the role a VN can play in facilitating communication between owner and veterinary surgeon (VS) about treatment options and quality of life of the animal. It has been said that cancer is ‘the most treatable’ of all chronic diseases (Moore and Frimberger, 2010). During the past decade, there have been many advances in the treatment of cancer in pets. The traditional modalities (surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy) are still the mainstay of treatment although there are several new treatment modalities now becoming more commonly available and used in small animal practice.

Definitive or palliative therapy

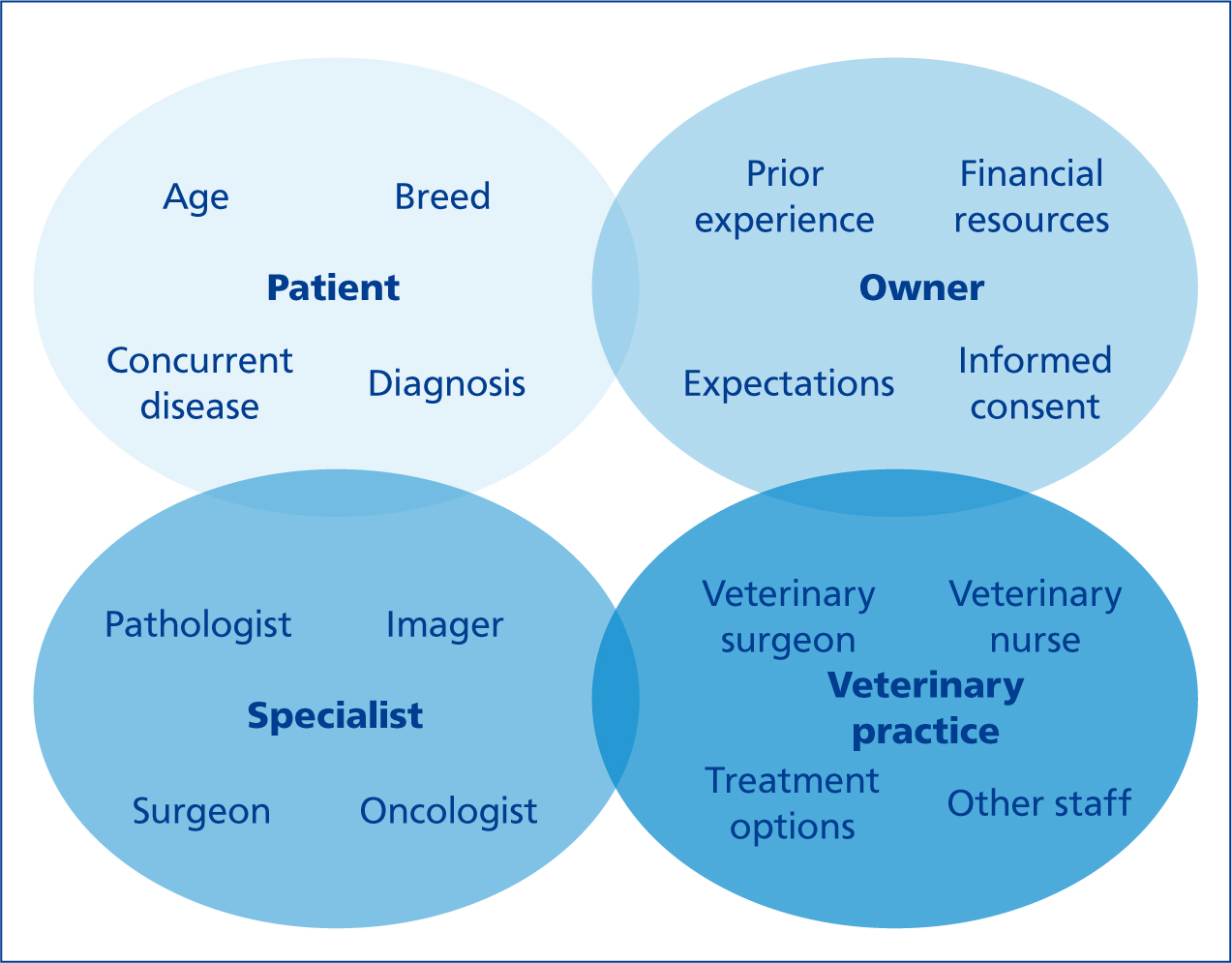

Veterinary oncology is the sub-speciality of veterinary medicine that deals with cancer diagnosis and treatment in animals. The methods and availability of treatment are improving almost daily with the development of new anticancer drugs and with more specialist oncologists and centres throughout the UK. Cancer treatment can be defined as being definitive or palliative, depending on the intent of therapy. Referral to an oncologist or other specialist should be offered so that all available options for the individual patient can be discussed (Figure 1).

Definitive cancer treatment can be defined as a treatment plan designed to potentially cure cancer using one or a combination of interventions including surgery, radiation, chemical agents and biological therapies. In human medicine, the primary purpose of definitive care is to establish a cure by destroying and removing all cancer cells from the affected patient. Although the aim is rarely to cure cancer in veterinary patients, definitive treatment with curative-intent surgery is suitable for small, low-to intermediate-grade tumours in an appropriate anatomical location.

In many veterinary situations, patients are not candidates for definitive treatment and palliative care is an alternative to immediate euthanasia. Palliative therapy is designed to relieve the clinical signs of illness and improve quality of life. It can be used at any stage of an illness if there are troubling signs such as pain, lack of appetite or vomiting. Palliative treatment in veterinary oncology includes using anti-cancer agents to reduce the effects of the cancer as well as drugs to control signs related to the side effects of the cancer or cancer treatment(s). With late diagnosis and advanced cancer being a common scenario in small animal practice, palliative treatment can help an animal to live more comfortably for the short-to medium-term or even longer in spite of a cure or remission being unlikely.

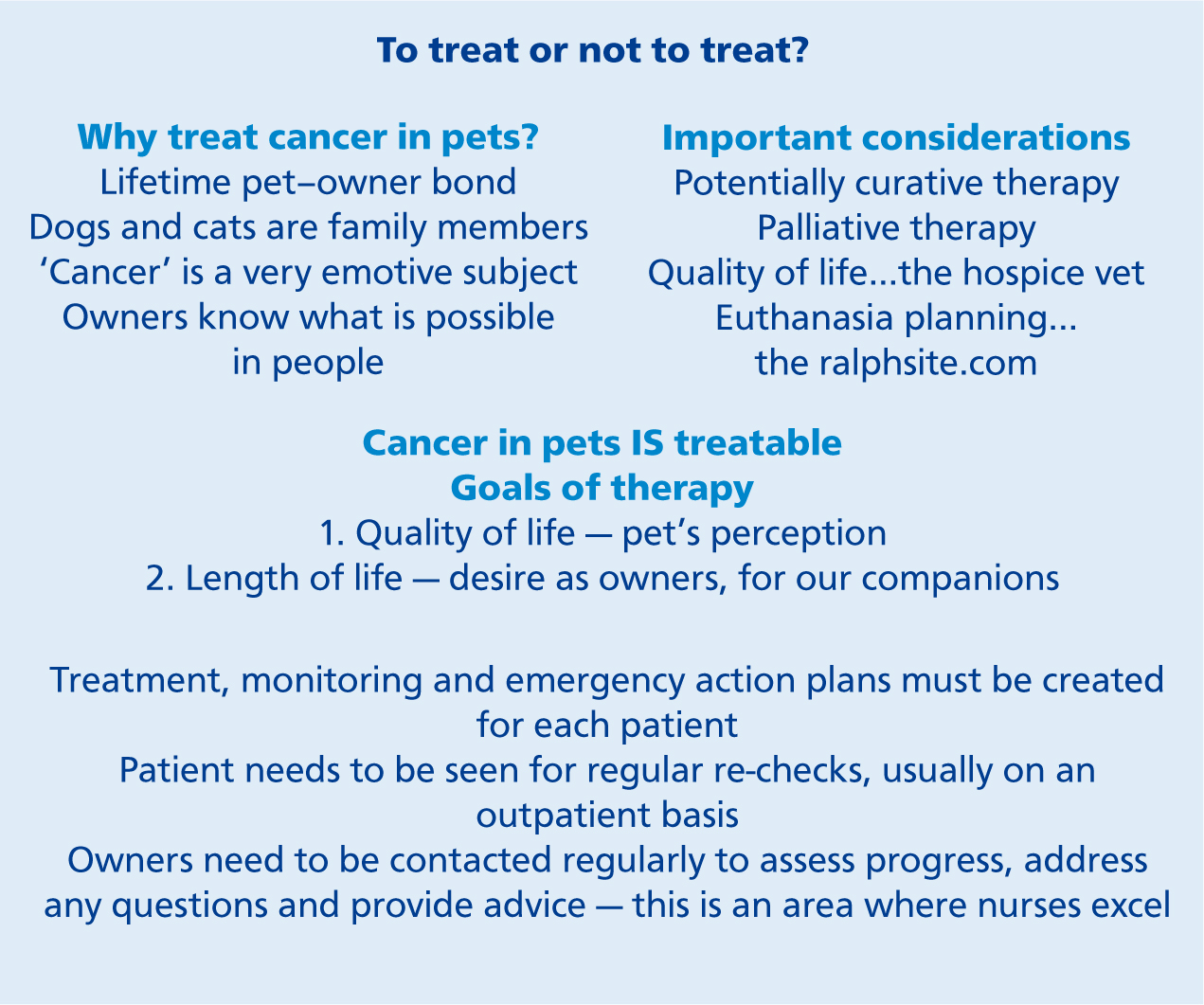

To treat or not to treat?

While it is recognised that most veterinary cancer patients will live a good quality life, at least in the short term, and many will die or undergo euthanasia due to another condition, it may be necessary to explain this to owners to reassure them that starting treatment is a viable option. Placing an emphasis on the fact that treatment can be changed or stopped as any point can also reassure owners that they will not have to commit to an entire course of treatment no matter how their pet responds. An understanding of the likely progression of disease based on the specific tumour type and good communication skills are very important before treatment is begun. Having said this, it should also be remembered that some owners will request euthanasia at the time of diagnosis in spite of how well their pet is doing and this decision must be respected.

To assist owners in making a decision about treatment, the significance of the cancer diagnosis in terms of tumour biology and behaviour must be explained to the owner(s) along with the likely outcome with and without treatment(s). Owners may need some time to come to terms with the diagnosis before a decision about treatment can be made; VNs can play an important role in reassuring owners that this is normal. Ensuring that the owner(s) understands what the VS has told them and providing written information can be very useful at this time. VNs can also point owners in the direction of reliable information in the form of printed leaflets or website resource addresses (Figure 2).

VNs are aware that the intent and costs of treatment, as well as the likely course of the disease, must be explained to the owner(s) before any treatment is begun. As a VN with a good relationship with the owner(s), this is a vital role in the team approach to cancer care. An honest discussion about quality of life and planning end of life decisions can be reassuring to some owners while it may be upsetting for others. Each case will be different and VNs are well placed to help the VS approach this subject at an appropriate time.

Treatment modalities

There are several different therapeutic methods or agents available for the treatment of cancer in companion animals (Table 1). These can either be used as stand-alone therapy or combined as multi-modal therapy. When multi-modal therapy of various combinations of surgery, radiation and chemotherapy are used to manage cancer in companion animals, good to excellent outcomes with limited morbidity can be achieved (Klein, 2003; Mason, 2016). It is essential to know that some chemotherapeutic drugs in combination with radiotherapy may result in increased toxicity (Hume et al, 2009); if a case is being considered for adjunctive chemo-therapy, this must be discussed with a radiation oncologist before any treatment is begun.

| Treatment modality | Examples |

|---|---|

| Surgery | Excision of small, low-to intermediate-grade tumours in appropriate anatomical locations with adequate margins as curative intent definitive treatment Palliative treatment for any tumour that is ulcerated or bleeding or causing pain or interfering with normal function, including tumour de-bulking or cyto-reductive surgery for tumours in locations where adequate margins are not achievable or curative-intent surgery has been declined; limb amputation for bone cancer; or splenectomy for haemangiosarcoma |

| Radiation therapy | External beam radiotherapy for analgesia and tumour control for nasal, oral, brain and bone tumours as well as tumours of the salivary or thyroid glands or tonsils, and intramuscular or subcutaneous or cutaneous tumours including localised lymphoma/melanoma or histiocytic sarcoma (available at six veterinary linear accelerator facilities in the UK) |

| Cytotoxic chemotherapy | Cytotoxic protocols using anti-cancer drugs; including intra-cavitary chemotherapy administration into a body cavity such as the chest or abdomen to maximise drug concentration where it is most needed and minimise side effects on the rest of the body |

| Metronomic chemotherapy | Low dose long-term protocols for various tumours such as nasal tumours and sarcomas |

| Electrochemotherapy | Local application of electric pulses to tumour tissue to cause electroporation of the cells; this makes the cell membranes more permeable to certain anti-cancer drugs that would not normally permeate |

| Tyrosine kinase inhibitors | Masitinib (Masivet, AB Science) |

| Photodynamic therapy | Local treatment for superficial tumours using a photosensitising agent and a specific wavelength of light to produce oxygen radicals that kill nearby cells |

| Plesiotherapy | Local external application of radiation (e.g. strontium wand* for squamous cell carcinoma of the eyelid in cats) |

| Immunotherapy | Using vaccines such as Oncept canine melanoma vaccine or Oncept IL-2 injection for feline fibrosarcoma (Merial) |

| Interventional radiological techniques | Using stents or chemo-embolisation to relieve urinary obstruction in cases with urogenital tumours |

| Other medical therapy | Analgesics, anti-inflammatories, antibiotics, appetite stimulants, gastroprotectorants, glucocorticoids, bisphosphonates (bone cancer) |

Surgery

In many cases, treatment involves surgery. As mentioned above, curative-intent surgery as a definitive treatment is suitable when all of the tumour cells can be removed without compromising quality of life. When this is not possible, palliative surgery can be combined with radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy — either before or after surgery (Table 2). The majority of owners report being pleased with the outcome of what may initially seem like radical surgery (e.g. limb amputation, maxillectomy, mandibulectomy or nosectomy (Figure 3)) as long as the procedure, postoperative care and appearance are explained (Fox et al, 1997; Aiken, 2003). A file of photographs or videos of cases can show owners what can be achieved and help them overcome any fears about aesthetics after surgery and healing. Placing emphasis on the degree of pain that a patient with a tumour is likely to be experiencing now or in the future, especially with bone involvement, can help owners to understand why palliative surgery is being suggested to improve quality of life.

|

|

With limb amputation, it is important to remember that even though osteoarthritis (OA) is commonly found during imaging to diagnose primary bone tumours, the majority of patients will adapt very well to three limbs with adequately managed mild-moderate OA. Use of advanced imaging for early detection of metastasis by computed tomography (CT) rather than by radiographs can result in what is called a ‘stage shift’. Stage shift refers to the diagnosis of cancer at an earlier stage due to the use of more advanced but often less available technology. By convention, a cancer is always referred to by the stage it was given at diagnosis, even if it gets worse or spreads. The effect of a so-called stage shift must be considered and interpreted with caution when planning treatment as there may be many months of good quality of life before the metastatic disease progresses. Limb-sparing surgery is usually offered in specific cases such as a primary bone tumour affecting the distal radius and/or ulna. Palliative amputation is likely to be more appropriate for cases with severe bone pain. The use of a prosthetic device is an option for patients in which amputation of a paw would provide good tumour control.

Radiotherapy

External beam radiation therapy (or teletherapy) is used as a palliative treatment either alone or in combination with surgery and chemotherapy for both tumour control and analgesia (Brearley et al, 1999; Bregazzi et al, 2001; Moore, 2002; Farrelly and McEntee, 2003; Mayer and Grier, 2006; Coomer et al, 2009; Kung et al, 2014) (Table 1). Radiotherapy requires a consultation with a veterinary oncologist to ensure that proper staging has been done to accurately determine the extent of the cancer and to determine whether radiotherapy will be of benefit in each individual case. Each time a pet undergoes radiotherapy, anaesthesia is required. The frequency and number of treatments will depend on the tumour type, location and whether the intent is definitive or palliative therapy. The effectiveness of radiotherapy depends on the dose used and this is limited by the tolerance of normal tissues surrounding the tumour to the effects of radiation as well as the ability to repair between treatments.

Cytotoxic chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the main treatment modality for the treatment of systemic cancers such as lymphoid and haematological malignancies (e.g. lymphoma and leukaemia) and metastatic carcinomas and sarcomas. Chemotherapy drugs can be used as a sole agent or in combination either before (neoadjunctive) surgery or radiation therapy, or after (adjunctive) surgery for solid tumours. Most chemotherapy protocols used in veterinary patients are well tolerated because they are more palliative, to minimise toxicity, compared with protocols used in human medicine (Mellanby et al, 2003; Tzannes et al, 2008; Bowles et al, 2010). Administration of anti-cancer drugs into a body cavity (intra-cavitory chemotherapy) can be useful in some patients, such as those with a neoplastic effusion, as permanent ports are well tolerated and facilitate drug delivery as well as allowing drainage of the effusion (Charney et al, 2005).

Tumour cells must develop their own blood supply through a process called angiogenesis in order to multiply and spread. Drugs that inhibit angiogenesis work by stopping or slowing down this process in order to control tumour growth. Traditional cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents are administered at maximally tolerated doses (MTDs). This first kills the endothelial cells lining the blood vessels of a tumour, followed by the death of the tumour cells. Typical chemotherapy protocols require a rest period between treatments to allow healthy cells to repair and regenerate and to minimise side effects. Unfortunately, the time between treatments allows damaged tumour blood vessels to recover as well and this may lessen the overall efficacy of the protocol.

There are many published cytotoxic chemotherapy protocols available. It is important not to treat these as recipes to be followed. Using anti-cancer drugs in practice requires specific training for the safety of the veterinary staff, patient and owners. Most chemotherapeutic agents are both toxic and mutagenic (capable of causing DNA mutation) and must be treated with great respect and handled with caution at all times. Careful attention to detail in required for personal safety at all times when handling and administering chemotherapeutic agents and bodily wastes from treated pets.

Metronomic chemotherapy

Metronomic chemotherapy is the administration of daily or every other day low-dose alkylating agent such as cyclophosphamide, chlorambucil or lomustine, usually in combination with a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) such as piroxicam or meloxicam, to inhibit angiogenesis. In some cases, the antibiotic doxycycline is also given. It has been used to treat gross disease as well as an adjunctive treatment for several tumours in cats and dogs, particularly nasal tumours, soft tissue sarcomas, splenic haemangiosarcomas or appendicular osteosarcomas (Lana et al, 2007; Tripp et al, 2011; London et al, 2015). Metronomic chemotherapy is most likely to be effective in cases where the primary tumour has been adequately controlled with the current standard of care (such as surgery ± radiation therapy and/or cytotoxic chemotherapy), and there is no evidence of spread but microscopic cancer cells are suspected to be present at undetectable levels. Metronomic chemotherapy may also be used in cases where conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy is contraindicated or when owners cannot travel or afford traditional protocols. It is essential that owners understand how and why metronomic chemotherapy is being used as they must be willing to monitor their pets closely for signs of drug intolerance and/or tumour progression.

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs)

There are two classes of TKIs that are able to target specific tyrosine kinase inside or outside the cell — monoclonal antibodies and small inhibiting molecules. Only the small inhibiting molecules are available in veterinary medicine.

A group of proteins called tyrosine kinases (TKs) are normal signalling proteins that cells use to transfer signals mainly coming from outside the cells to the nucleus. There are different cascades of signalling proteins which can be switched on or off to regulate cell functions (for example, to survive, die or proliferate). TKs have been found to be over-expressed or mutated in many human cancers, resulting in a ‘proliferation signal’ that causes tumour growth. TKs are intranuclear, intracytoplasmic or transmembrane receptors (TKRs) on the cell surface, with the latter being the most important in veterinary medicine. The first step in the signalling cascade is the binding of an extracellular growth factor to the receptor in the cell surface.

The most important TKRs in veterinary medicine are stem cell factor receptor (c-kit), platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) because the available drugs mainly block these receptors. There are two drugs licensed for use in dogs that have shown a survival benefit (Hahn et al, 2008; London et al, 2009; Blackwood et al, 2012): masitinib (Masivet, AB Science) which is licensed for the treatment of non-resectable dog mast cell tumours (Grade 2 or 3) with confirmed mutated c-kit TKR, and toceranib (Palladia, Zoetis) which is licensed for the treatment of non-resectable Patnaik grade II (intermediate grade) or III (high grade), recurrent, cutaneous mast cell tumours in dogs. These drugs have been shown to improve response rates in several other tumours, particularly some carcinomas (London et al, 2009; 2012; Mitchell et al, 2012).

Other medical therapy

Anti-inflammatory and analgesic medications

A variety of tumours are associated with clinically significant numbers of inflammatory cells and will benefit from the use of anti-inflammatory therapy (Doré, 2010; Queiroga et al, 2010; Epstein et al, 2015). NSAIDs can be used for their anti-inflammatory and mild analgesic effects as well as potential antineoplastic action (Table 3). The cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitory NSAIDs, such as piroxicam, meloxicam and carprofen, are now commonly used in the treatment of carcinomas and sarcomas. Outcomes in dogs with transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder (± urethra) or inflammatory mammary carcinoma are similar to or may be improved with the administration of COX-2 inhibitory drugs to cytotoxic chemotherapy agents (Marconato et al, 2009). As mentioned previously, NSAIDs are often included in metronomic chemotherapy protocols and/or as adjunctive treatment after surgery to remove/de-bulk carcinomas or sarcomas (Hayes et al, 2007).

| Drug class/type with examples | Indications | Side effects/warnings/contraindications |

|---|---|---|

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), specifically Cox-2 inhibitors — carprofen, ketoprofen, meloxicam, piroxicam, tolfenamic acid | Mostly antiinflammatory with less analgesic effect; may have antineoplastic effect | Generally well tolerated; decreased appetite, vomiting, diarrhoea, dark or tarry stools, behavioural changes; rarely, increased water intake, increased urination, pale/yellow gums or skin, incoordination, seizures; stomach protectants, such as famotidine, can be used as a precaution; should not be given to pets that are not eating or have stomach ulcers, major kidney/liver dysfunction, known bleeding disorders, or previously not tolerated NSAIDs |

| Para aminophenyl derivative — paracetamol | UK licensed form combined with codeine for analgesic therapy in dogs only | Occasional constipation may occur due to codeine content; do not exceed stated dose/duration of treatment; do not administer NSAIDs concurrently or within 24 hours of each other; use is contraindicated in animals suffering from cardiac/hepatic/renal disease, where there is a possibility of gastrointestinal ulceration/bleeding or where there is evidence of a blood dyscrasia or hypersensitivity to the product; do not use in cats or snakes |

| Structural analogue of GABA (an inhibitory neurotransmitter) - gabapentin* | For the treatment of chronic pain, particularly of neuropathic origin | Mild sedation and ataxia at higher doses; use with caution in animals with liver/renal dysfunction; should be given at least 2 hours apart from oral antacids; use with hydrocodone/morphine may increase gabapentin levels side effects; do not stop abruptly — decrease dose gradually |

| Opioidergic/monoaminergic drug — tramadol* | Works best for chronic pain when combined with other pain relievers | Generally well tolerated; occasional-rare side effects include anxiety, agitation, tremor, poor appetite, vomiting, constipation/diarrhoea |

| N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist - amantadine* | Works best combined with other pain relievers | Generally well tolerated; may cause gastrointestinal effects or agitation that tend to resolve with time; use with caution and decrease dose in patients with liver/kidney dysfunction, congestive heart failure or and seizures |

| Opioids — buprenorphine, butorphanol, methadone; codeine, fentanyl, morphine | Management of mild-severe pain, usually in combination with other analgesics | Effects are dose dependent, vary with the type of opioid; may include sedation, respiratory depression, dysphoria, nausea/vomiting and histamine release; constipation, abnormal pain sensitivity and effects on gastrointestinal motility may need to be addressed |

While the true prevalence of pain associated with cancer in companion animals is not known, most oncologists agree that it is likely to be underestimated and may go undiagnosed. Pain due to cancer may result from direct invasion of tumour cells into tissues, stretching of viscera and distension or obstruction of organs. A holistic approach to chronic pain relief may require multi-modal therapy (Fan, 2014; Mathews et al, 2014; Epstein, 2015) (Table 2); for example, using a combination of NSAID + tramadol/gabapentin + paracetamol codeine (Mason, 2016). Using several medications that have different mechanisms of action can allow achievement of better pain control and reduce the incidence of side effects. Other analgesics such as paracetamol (± codeine), opioids, tramadol, gabapentin or amantadine also may be used for pain relief although the last three are not licensed in the UK and should be used under the prescribing cascade (Table 3). While opioid analgesics are the most powerful and perhaps most useful drugs for managing pain, many clinicians avoid using them because of a fear of perceived adverse effects. These concerns can be successfully addressed and usually avoided and these drugs are becoming increasingly popular for longer-term chronic pain management in the home environment. A good understanding of how opioids work within the peripheral and central nervous system and using them in a multi-modal approach is essential.

Tramadol is a non-narcotic that can be used with an NSAID or opioid. Gabapentin may be preferred for neurological pain, but may cause sedation or ataxia at higher doses. Amantidine is an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist. Glucocorticoids tend to be less effective as analgesics compared with NSAIDs and are less suitable for treating large tumours other than mast cell tumours (MCTs). NSAIDs should not be used in combination or with glucocorticoids because of increased risk of gastrointestinal side effects. A wash-out period of 4–7 days should be allowed between stopping a glucocorticoid or another NSAID and starting a new NSAID.

Not all cases will benefit from or even tolerate all analgesics or combinations; some will develop unacceptable side effects. Treatment should be tailored to each individual case and there are two basic approaches one can take:

If no pain is obviously evident, then improvements in demeanour can be used to assess the effects of analgesia.

Antibiotics

Antibiotics are indicated in patients with secondary infections, for example, with oral tumours or bladder/urethral carcinomas (Boudreaux, 2014).

Appetite stimulants

Appetite stimulants may be used for short-term support although their use needs to be carefully evaluated for individual patients. Examples include cyproheptadine, diazepam, megestrol acetate and mirtazapine Other forms of nutritional support, such as a feeding tube (Figure 4), may be more appropriate for certain cases and in certain situations. Anti-emetics should be considered before using appetite stimulants as a lack of appetite may be the first sign of nausea. Examples include butorphanol, dolasteron, maropitant, metoclopramide and ondansetron.

Gastroprotectants

For cases at risk of gastric ulceration due to other medications or the type of cancer such as MCT, gastroprotectants including sucralfate or histamine (H2) receptor blockers such as famotidine, ranitidine and omeprazole may be of benefit.

Glucocorticoids

There are several specific indications for glucocorticoid use in cancer treatment, including as part of a multi-agent chemotherapy protocol, for lymphoid neoplasia when a full cytotoxic chemotherapy protocol is not an option and for MCTs, particularly when there is associated inflammation and/or oedema. Prednisolone is the glucocorticoid most often used and it may relieve some of the clinical signs associated with paraneoplastic hypercalcaemia. It can be used to increase blood glucose levels in cases of insulinoma. It is essential to collect tissue samples and reach a definitive diagnosis before starting to use glucocorticoids in order to maximise the response to glucocorticoids once treatment is started.

Bisphosphonates

Bisphosphonates such as alendronate, pamidronate and soledronate may be used to treat cases with primary bone tumours or metastasis. These drugs work by inhibiting osteoclast activity and can be used to manage some cases of paraneoplastic hypercalcaemia as well (Tomlin et al, 2000; Fan, 2014).

Conclusion

Treating cancer in pets is much like treating other chronic diseases such as heart or kidney failure; all of these diseases can be fatal but they can also be managed to maintain quality of life. With an emphasis on early, accurate diagnosis, including staging, treatment is most successful with small, non-invasive tumours that have not spread. Delayed diagnosis can result in less than optimal treatment options if the tumour is very large or has spread by invasion or metastasis. Treatment planning with a focus on targeting therapy to the individual pet is essential and requires good communication amongst the veterinary team and with the owner.