Part 1 of this series focused on the role of nutrition to optimise skin health, particularly where skin or coat conditions are present. This second article will review the key nutritional considerations needed for dogs with cutaneous adverse food reactions, particularly the part that diet plays in the diagnosis and management of dogs with food allergies and intolerances. It will also explore the role of the veterinary nurse in optimising the likelihood of canine patients starting on an elimination diet trial, as well as how they can maximise the likelihood of successful adherence to the trial.

What is an adverse food reaction?

An adverse food reaction (AFR) describes an abnormal response as a result of ingestion of a food or food additive, with cutaneous adverse food reactions (CAFRs) — the main focus of this article — being those that result in dermatological signs. AFRs covers two key categories of reactions: food allergies and food intolerances. CAFRs are the third most common cause of canine allergic skin disease, after allergies from parasites and environmental allergies. They account for a much smaller proportion of cases of dermatological disease than flea bite hypersensitivity or atopic dermatitis; despite owner misconceptions that they are a frequent cause of skin conditions food allergies only actually account for around 1% of dermatological cases (Verlinden et al, 2006).

What is the difference between a food allergy and a food intolerance?

With a food intolerance, the pet will show an adverse reaction after eating a food, but the process that causes the reaction is not an immune-mediated one. Both gastrointestinal and dermatological signs may be present, but gastrointestinal signs such as vomiting or diarrhoea tend to be more commonly seen than skin symptoms, usually occurring relatively rapidly after consumption of a food. Intolerances can be split further to metabolic, pharmacological, toxic and idiosyncratic food reactions (Gaschen and Merchant, 2011) (Box 1).

Box 1.Classification of food intolerancesFood intolerances can be classified as:

- Metabolic e.g. lactose intolerance (lacking lactase enzyme to digest lactose, resulting in maldigestion and malabsorption, and consequent diarrhoea)

- Pharmacological e.g. due to consumption of histidine (the precursor to histamine) in fish such as tuna or mackerel — particularly if being fed a homemade or raw diet

- Toxic e.g. after consumption of bacterial toxins

- Idiosyncratic i.e. unpredictable reactions to a food, reaction to a food additive

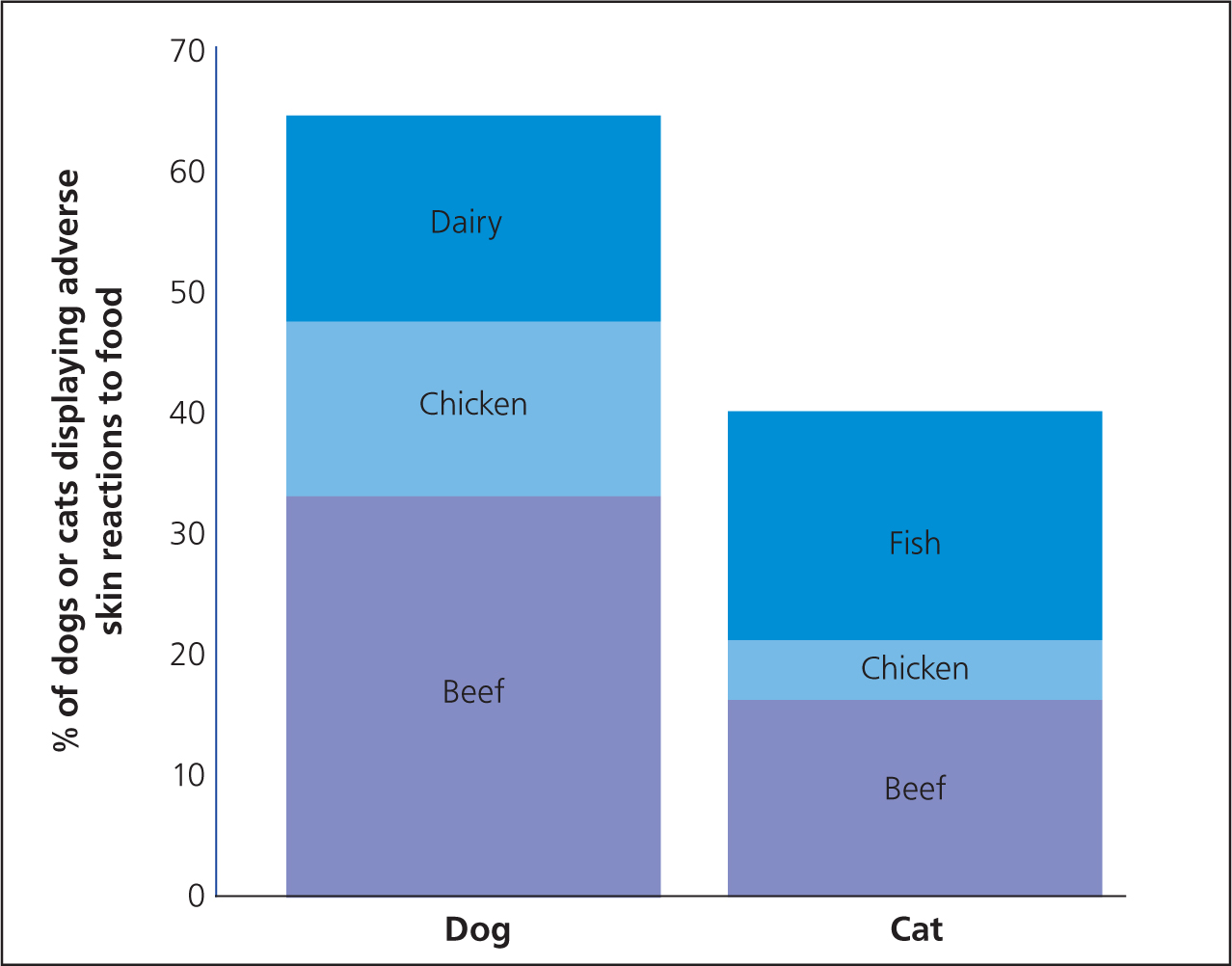

A food allergy occurs when a pet has a reaction to a food component that involves the immune system. While it may be a type I, IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reaction, cell-mediated and mixed reactions also occur (Verlinden et al, 2006). Impairment of the mucosal barrier and loss of oral tolerance are risk factors for the development of a food allergy (Verlinden et al, 2006). A food allergy requires prior exposure to the ingredient, and often results after feeding a food for a 2 years or more (Verlinden et al, 2006). Dermatological signs, particularly pruritus and inflammation, tend to be more commonly seen than gastrointestinal signs, although again one, other or both may be seen in any individual patient. Food allergens are almost exclusively proteins or glycoproteins, and in dogs the most commonly reported allergens are beef, dairy products, chicken and wheat (Figure 1; Mueller et al, 2016). The size and structure of the protein helps determine its ability to induce hypersensitivity. Most allergens have a molecular weight above 20 000 Daltons—large enough to have sufficient complexity to interact with antibodies or T cell receptors. However, they also have to be small enough to pass through the mucosal barrier, and are usually less than 70 000 Daltons (Sicherer and Sampson, 2010).

It can be challenging to make the distinction between an intolerance and an allergy, but the term ‘adverse food reaction’ can be used to cover both types of response, since this does not indicate the underlying immunological or non-immunological mechanism. Since food allergies more commonly present with dermatological signs than food intolerances, they will be the main focus of this article.

Diagnosis of an adverse food reaction

Diagnosis of food allergies and intolerance can be a challenge in clinical practice. There is no quick and simple test: testing for serum food-specific IgE and IgG showed low repeatability and, in dogs, a highly variable accuracy (Mueller and Olivry, 2017). Therefore, intradermal skin and blood serum allergy tests are unreliable and are not recommended (Kunkle and Horner, 1992; Mueller and Olivry, 2017). While such tests do not determine if a pet has an allergy to a particular protein, they can indicate exposure to a particular ingredient or antigen, which can help to inform selection of a novel protein for an elimination diet.

The only reliable method of diagnosis of an AFR is an elimination diet trial with a fully hydrolysed or novel protein diet containing a limited antigen content. Improvements in dermatological (and/or gastrointestinal symptoms where present) should be documented after starting the diet. Generally, if clinical signs seen in a patient are as a result of an AFR, improvements in gastrointestinal signs should start to be seen within 2 weeks of starting an appropriate diet (Guilford et al, 2001), and an elimination diet trial of 2 to 4 weeks may be sufficient (Roudebush et al, 2000). Dermatological improvements tend to take longer, with improvements starting to be seen within 6 to 8 weeks of starting on the diet. Generally, elimination diet trials should last at least 8 weeks to diagnose CAFRs successfully in dogs, with 90% of animals responding during this period (Olivry et al, 2015).

To confirm an allergy, provocative exposure testing by re-challenging with the previous food in order to prove or disprove the presence of food allergies should be done; if an AFR is present, it should result in re-development of symptoms, and this will usually occur within a few days of starting back on the previous diet, although it can take up to 2 weeks. However, many owners prefer not to re-challenge their pet if improvements are seen and may wish to stay on the test diet longer term, or challenge with an alternative diet once maximum improvements in clinical signs have been seen. It should be cautioned that without provocation tests, it is difficult to confirm an AFR is present, as various additional properties of the elimination diet might be responsible for the improvements seen.

Ultimately, management of a food allergy or food intolerance requires life-long avoidance of the food component to which the individual is allergic or intolerant. Some-times, an elimination diet trial may identify the individual ingredient(s) thought to be responsible for the AFR. In other cases, however, while an AFR may be identified, the offending ingredient(s) are not determined and an owner may wish to remain on a potential elimination diet trial option (discussed below) longer term, or be cautious when challenging with alternative foods since they may not know whether that diet contains ingredients to which their dog may be sensitive.

How to choose between a novel protein and hydrolysed diet for an elimination diet trial

There are now a number of commercially available novel protein and hydrolysed diets available for dogs, which use slightly different ingredients. These are preferable to a home-cooked diet utilising a single protein and single carbohydrate source because such diets are generally unbalanced, unsuitable for long-term feeding, and labour-intensive for owners. Generally, the author would recommend a hydrolysed diet is selected for an elimination diet trial, rather than a novel protein diet, as selecting appropriate novel proteins can come with a number of challenges. In order to ensure that the diet selected is truly ‘novel’, a comprehensive dietary history is needed, and the veterinary nurse plays a key role in taking this history. Diet history forms such as that shown in Figure 2 may be helpful when obtaining this and will maximise the amount of information received. Open questions and requesting photos of food fed can also be helpful. However, it may be difficult to fully ascertain all antigens a dog has been exposed to. For example, the diet history of a rescue animal is likely to be unknown. Even if the caregiver has had the dog since a puppy, it may be difficult for them to remember every food they have fed and obtain packaging to identify all ingredients within them.

Information on all treats the dog has been given is also needed. If others treat the dog or the dog scavenges, these could complicate identifying a novel protein. Furthermore, even if a caregiver can remember all foods their pet has been fed, studies have highlighted that some commercial diets — including diets marketed for management of AFRs — contain undeclared ingredients (Horvath-Ungerboeck et al, 2017) so an owner or veterinary professionals may not be aware that their pet has been exposed to some proteins. There may also be the potential for cross-reactivity between food allergens with antigenic similarity, which can further complicate diagnosis of an AFR after starting on a novel protein diet. As a result of these challenges, novel protein diets are generally better placed as a maintenance diet after diagnosis of a CAFR, rather than as a diagnostic tool.

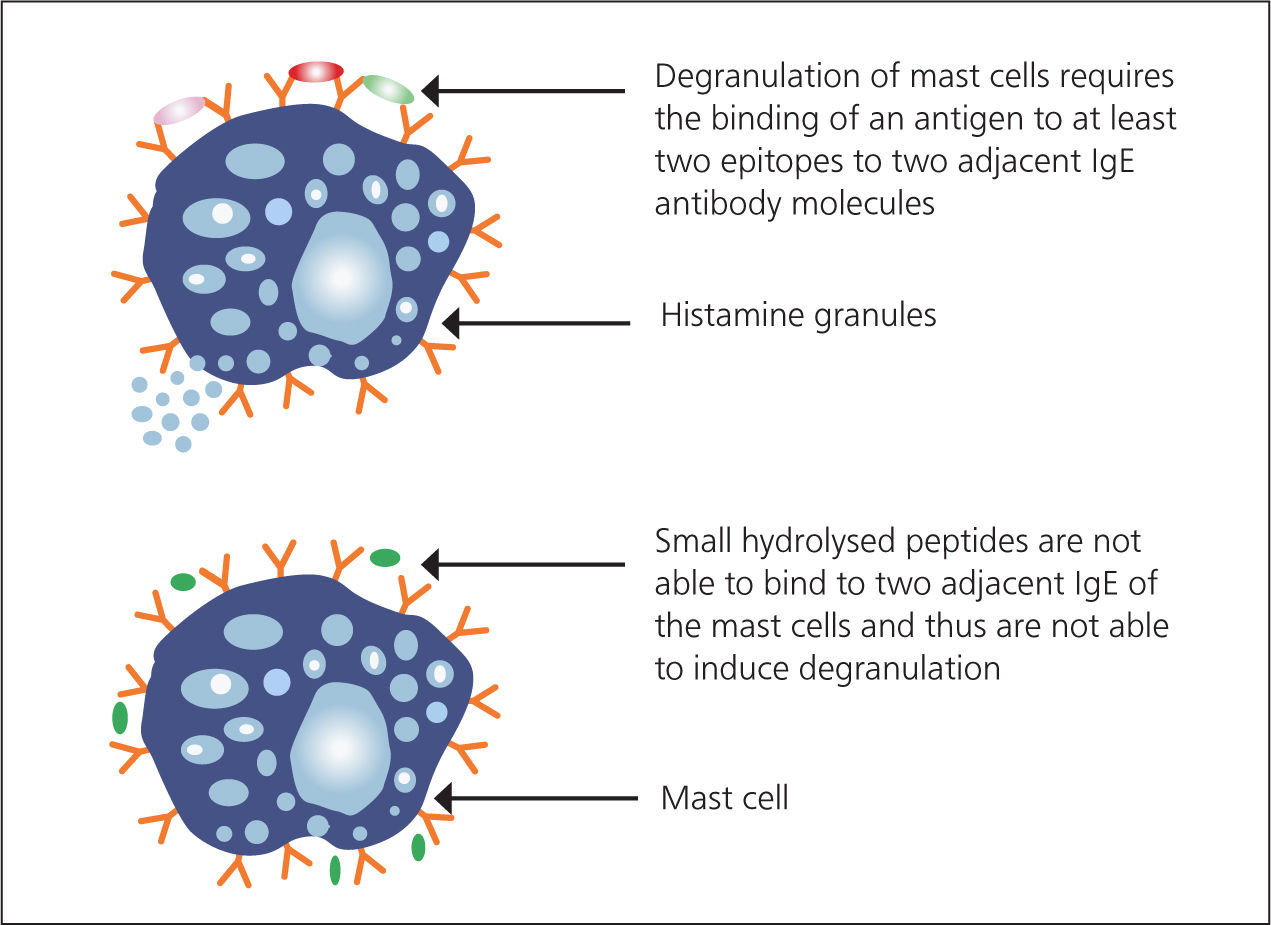

Hydrolysed diets are based on protein sources that have been enzymatically cleaved to a very small size, reducing their molecular weight to below that needed to stimulate an immune response (Figure 3). They can be particularly helpful where it is difficult to ascertain a novel protein for a patient. There are several commercially available fully hydrolysed diets, which use different protein sources within them. They generally have strict quality control processes to minimise antigenicity of the diet and maximise the likelihood of efficacy. They may also be increased in omega-3 fatty acids to maximise the natural anti-inflammatory processes within the skin. Their main disadvantage is that the hydrolysis process can make proteins unpalatable, so acceptance of these diets may be a challenge in some patients, although palatability is generally deemed to be good and does vary between products. They also will not successfully diagnose CAFRs in every case. It has been shown that dogs allergic to the native protein of the hydrolysed diets may still react even when that protein has been hydrolysed (Bizikova and Olivry, 2016), so selection of an appropriate hydrolysed diet, avoiding any native protein that there may be high clinical suspicion is responsible for a food allergy, may be sensible in some cases.

How can we encourage caregivers to partake in an elimination diet trial and feed an appropriate food?

Caregivers may have a number of misgivings before starting an elimination diet trial, and the veterinary nurse has a crucial role to play in supporting the owner and encouraging them to transition onto an appropriate diet, as well as providing education from the outset.

Lack of client compliance is generally the biggest reason for failure of dietary trials, often resulting from insufficient client education concerning expectations and especially length of the trial (Gaschen and Merchant, 2011). It has been shown that without improved client education, 52% of elimination trials would fail at the time of follow-up compared with a failure rate of 27% after better client education was instituted (Chesney, 2002).

One of the main concerns an owner may have is the advice that they can feed only one food for a prolonged period of time. Discussion of timescales can be important. Historically, a minimum of 12 weeks had been recommended for a diet trial, but as previously discussed, improvements should be seen much earlier than this if the clinical signs a patient displays are a result of an AFR. Providing shorter timescales can make it feel much more achievable for owners and may, in some cases, make the difference between a caregiver opting to try a diet trial or feeling they can simply not achieve what is being asked of them. Improvements should be seen in gastrointestinal signs within 2 to 3 weeks, and/or no improvements in dermatological signs within 6 to 8 weeks. If no such improvements are seen at that stage, it suggests either there is not full compliance or clinical signs are not because of an AFR, in which case the diet trial can be halted. Alternatively, in a small number of cases, if suspicion remains high that an AFR is contributing to clinical signs an alternative hydrolysed diet may be sought, as a small number of cases may not respond to one diet but will respond to another.

Some owners may be reluctant to begin an elimination diet trial with a fully hydrolysed diet that may cost more than the diet they have been feeding if they perceive that they have already been on one (or several) of the many commercially-available pet foods that claim to be ‘hypoallergenic’ and this has not improved their dog's clinical signs. It is important to be aware that ‘hypoallergenic’ is an unlegislated term. Manufacturers may use the term ‘hypoallergenic’ as a claim when one or several protein sources have been excluded from the pet food. However many of these ‘hypoallergenic’ diets still contain multiple, intact protein sources, capable of causing an immune reaction. Therefore, if a pet is allergic to any of the proteins within that particular diet they will still react to it when eaten. The only pet foods that are truly suitable to eliminate the risk of an AFR are those containing a limited number of different protein sources where all of these proteins are fully hydrolysed (for example: Purina PRO PLAN® Veterinary Diets HA Hypoallergenic, Hills z/d, Royal Canin Anallergenic). Explanation of this can be very important to help a caregiver to understand why an alternative diet has been recommended.

How can we maximise pet and caregiver compliance during an elimination diet trial?

In addition to supporting caregivers when making the decision to participate in an elimination diet trial, veterinary nurses can be extremely important to maximise the likelihood of success of this trial. Adherence to successfully diagnose or exclude an AFR as a cause of clinical signs can be very challenging, both for caregivers and pets, and communication and support are crucial. A clear explanation before the diet trial begins to explain the process and importance of strict adherence to the trial is crucial. As well as discussing timescales and the rate at which an owner may start to see some improvements, this should also involve setting owner expectations and discussing any owner concerns.

Regular check-ins by phone as well as at the surgery can help owners to feel supported. This may involve a discussion of how the caregiver is getting on with the trial, any difficulties they are experiencing, and ensuring that family and friends are also all participating in the trial.

The caregiver should understand that they must feed an appropriate, fully hydrolysed, diet, and that this is the only food fed. While this may feel daunting to some owners initially, selection of an appropriate diet that the pet enjoys is critical. Palatability varies between different products, so in some cases more than one brand might need to be tried before there is good acceptance. Consideration of the texture(s) of the diet offered may be key in some cases too. For example, some veterinary hydrolysed diets are available in a wet form as well as a dry form, which may be important to an owner or their dog, and they may find the elimination diet trial easier to complete when able to offer both textures.

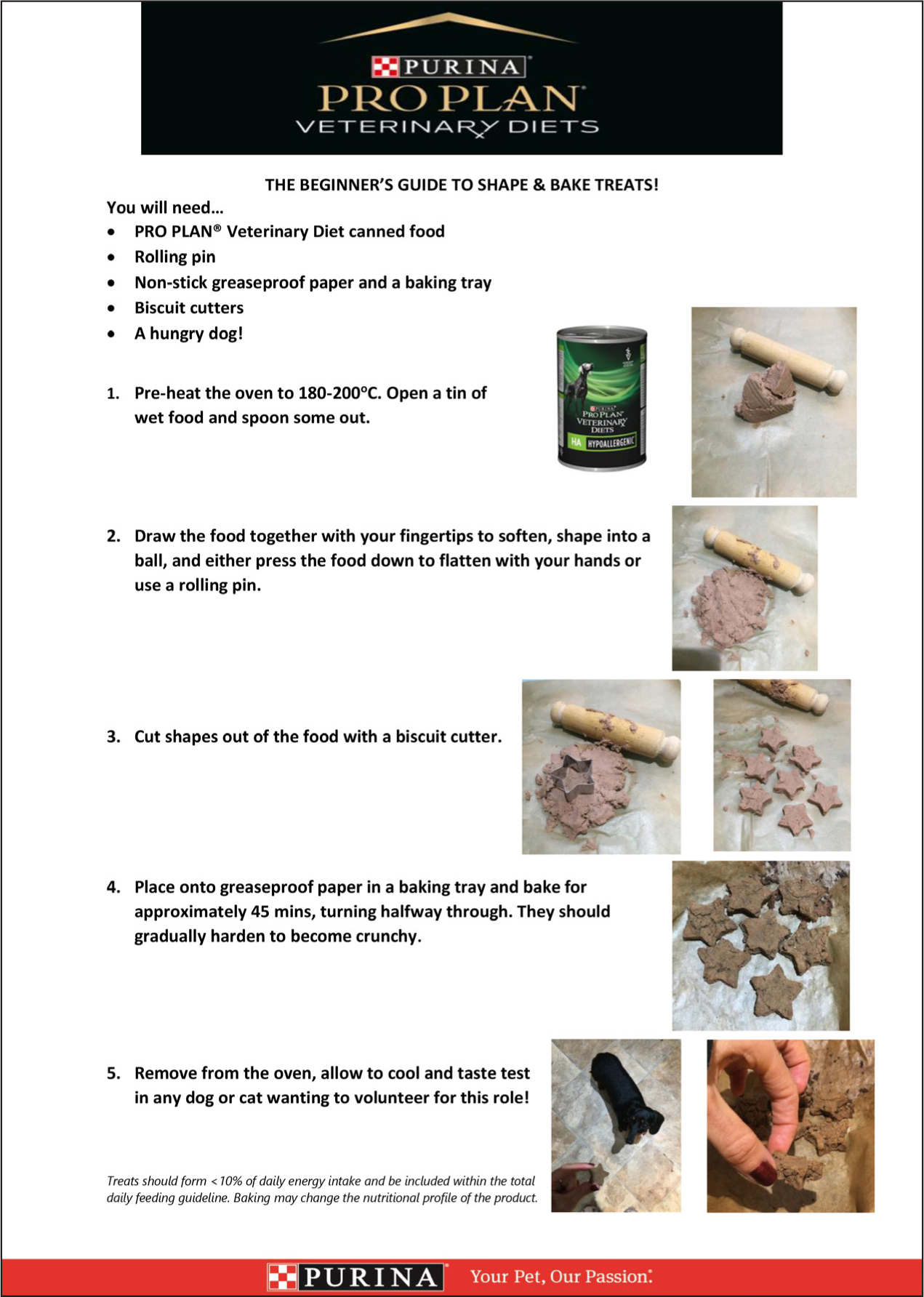

Treats can still be possible during an elimination diet trial. There are commercially available fully hydrolysed treats, or caregivers may wish to create their own. For example, ‘shape and bake’ of a wet fully hydrolysed diet, creating or cutting small shapes that can be gently baked in the oven can be an excellent way for an owner to feel they are still treating — something that may be important to the caregiver-pet bond (Figure 4). The author has also found this to be a successful way of involving the whole family, including children, in the trial.

A number of factors can interfere with any elimination diet trial started, and caregivers should be aware that flavoured medications, toothpaste, treats and scraps, eating faeces, discarded and dropped food, licking dirty plates, and ‘empty’ bowls still containing other pets' food should all be avoided for the duration of the diet trial. Bins or any other potential food sources should also be made inaccessible and the dog should be fed separately from any other pets in the household.

Encouraging use of a food diary throughout, documenting the daily diet, clinical signs, and any ‘confessions’, where an owner is aware that their dog has eaten anything that is not the elimination diet, can be really helpful when interpreting clinical signs. Honesty should be encouraged.

What happens after an elimination diet trial and successful diagnosis of a CAFR?

There tend to be two key choices after successful diagnosis of a CAFR: either a pet can remain on the fully hydrolysed elimination diet for life, or the pet should be challenged with an alternative diet. As mentioned above, in order to categorically diagnose a CAFR to be the cause of the clinical signs, it is recommended that patients are re-challenged with their original diet. However, many caregivers are reluctant to do this. If so, transitioning to a commercially available novel protein, limited antigen diet may be an appropriate alternative. Several different options are available, and all tend to avoid the most commonly identified canine food allergens. In some cases, there may be a relapse of clinical signs: in such cases, the patient should be promptly moved back to the hydrolysed diet. However, where possible, maintenance on a novel protein diet may be a more preferable option if the dog can tolerate it: they are specifically designed for dermatological support, tending to be higher in protein levels and skin-supportive nutrients and maximising the strength of the skin barrier longer term.

Conclusions

Diagnosis of canine CAFRs can be challenging but is also very rewarding. Hydrolysed and novel protein diets play an important role in the diagnosis and long-term management on CAFR, but alongside diet, support from the veterinary nurse can maximise the likelihood of success of an elimination diet trial, both before initiation of the trial and throughout the process. Ensuring a caregiver feeds an appropriate diet throughout, encouraging a climate of trust, and trying to work together to find solutions to any challenges they may experience are key to success of such trials, and may make a significant difference to the quality of life of the pet.

KEY POINTS

- Cutaneous adverse food reaction (CAFR) describes an abnormal response to ingestion of a food or food additive resulting in dermatological signs, most commonly pruritus. The terminology can be used to describe both food allergies and food intolerances. Adverse food reactions (AFRs) can also manifest with gastrointestinal signs.

- Food allergies account for around 1% of dermatological cases. The most common canine food allergens are chicken, beef and dairy.

- The only reliable way to diagnose an AFR is an elimination diet trial using an appropriate diet — either a novel protein diet, or, more commonly, a fully hydrolysed diet. Hydrolysed diets are recommended where possible given the difficulty identifying a truly novel protein source for an individual patient.

- Improvements in gastrointestinal signs should be seen within 2–3 weeks of commencing a diet trial, and skin signs within 6–8 weeks. To confirm diagnosis of an AFR, clinical signs should relapse on subsequent provocation with the previous diet.

- Lack of client compliance is generally the biggest reason for failure of dietary trials. The veterinary nurse plays an important role in support and education and to maximise the likelihood of a successful elimination diet trial.

- Identifying an appropriate food for the trial that meets the need of both pet and owner, and discussion of timescales, realistic expectations and factors that could interfere with success of a diet trial are all important areas that veterinary nurses can support caregivers with before and throughout the diet trial.

- Ultimately, long-term management of an AFR requires avoidance of the offending ingredient(s). Several different dietary options may be possible to achieve this.