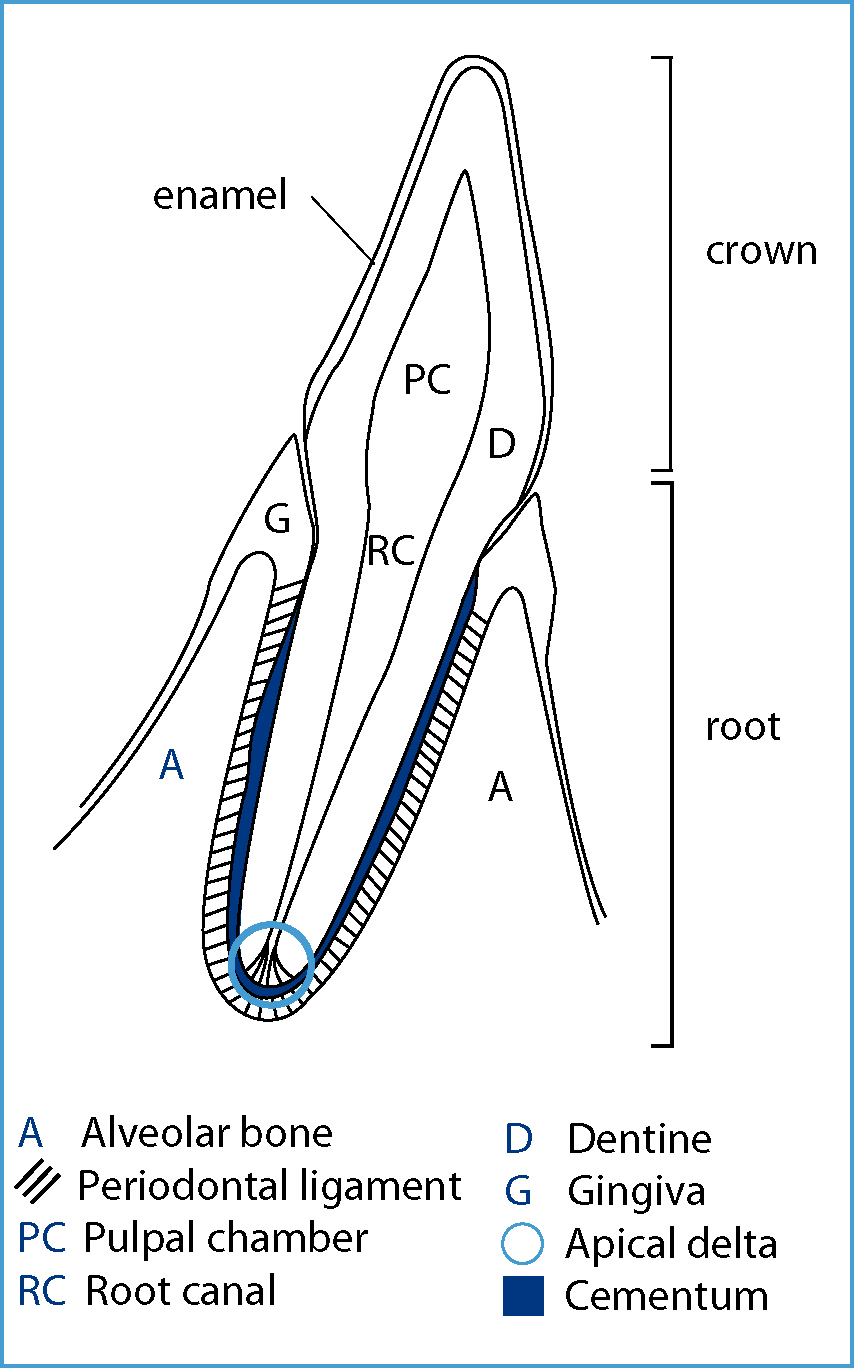

The pulp is the embryological and functional tissue contained within the dentine of a tooth, and the pulp-dentine unit is collectively termed the ‘endodontium’. The pulp cavity is correctly known as the ‘pulpal chamber’ within the crown of a tooth and the ‘root canal’ within the root, and the root canal opens apically into the surrounding periapical tissues via the apical delta (Figure 1).

The endodontium is responsible for the vitality of a tooth, and contains:

As with any other tissue in the body, the pulpal tissue will react to different stimuli by initiating an inflammatory response, and the stimulus could be bacterial ingress, chemical irritation, thermal changes or disruption of the apical blood supply. Pulpitis is inflammation of the pulp, which can be categorised as detailed in Table 1.

| Pulpitis | Acute or chronic | Relates to the rate of onset and severity of clinical signs, and the histological appearance of the pulp, all of which is dependent on the nature of the insult |

| Partial or total | Dependent on the extent of the pulp involvement, which is dependent on the nature of the stimulus | |

| Open or closed | Open means there is a direct communication between the pulp and the oral cavity |

If the pulpitis is untreated, is irreversible or is caused by infarction following trauma, the pulp will eventually become necrotic, which means the tooth is no longer vital and requires treatment (Gorrel, 2004; Holmstrom, 2011). The veterinary surgeon (VS) and veterinary nurse (VN) inspecting an oral cavity must be aware that the most common route for the further spread of inflammation from a pulp that is inflamed or necrotic is apically; down through the root canal and out into the periapical region, which can then result in further problems such as periapical abscess formation.

The potential endodontic treatments available for affected teeth include:

This article will focus on RCT as this is the most commonly performed endodontic procedure in mature teeth, and is the recommended treatment for many common diseases affecting the endodontium of adult animal teeth (Gorrel, 2004)

RCT

Standard RCT, or pulpectomy, is indicated when there is irreversible pulp pathology, and is performed in mature, permanent teeth (Holmstrom, 2011). As previously mentioned, it is typically a procedure associated with the larger, strategic teeth such as the canines and carnassials (Girard et al, 2006). It is a time-consuming procedure which requires great attention to detail, but when performed by a specialist VS it is often quicker and less traumatic to perform RCT in periodontically sound teeth than extracting them. RCT is generally no more expensive than the surgical extraction of a healthy tooth, and if performed well it will last for the lifespan of the animal (Gorrel, 2004; Holmstrom, 2011). RCT can also avoid post-operative complications associated with trying to extract healthy, strategic teeth such as:

The objectives of RCT are to clean and disinfect the pulp chamber and root canals before filling them with a non-irritant antibacterial material (Gorrel, 2010). This will seal the apex of the tooth, and finally the access and exposure sites are closed with a restorative material.

The procedure for performing RCT is logical and sequential, but it must be reiterated that experience and patience are required for it to be successful. The procedure can be summarised as follows:

If there is a pulp chamber in the remaining portion of the tooth crown above the access point, this must also be cleaned, prepared, filled and sealed as outlined above. This can be achieved through another access hole in the coronal aspect of the tooth, or through the exposure site in cases of a fracture. It is essential that no pulp tissue remains in the tooth. It must be noted that a fractured tooth receiving RCT should not be restored to its original shape and size, as the biting forces in animals, dogs especially, are great and will cause failure of the restoration (Gorrel, 2010).

Once restored, the RCT should be monitored radiographically 4 to 12 months later; the frequency of checks is the decision of the VS and will be based on the success of the initial treatment and the resulting findings from follow-up radiographs. If a monitoring radiograph reveals evidence of apical disease the VS may recommend performing the RCT again, in conjunction with a surgical endodontic treatment to achieve retrograde filling of the canal and facilitate appropriate treatment of the apical area (Gorrel, 2008), or they may recommend extraction if the pathology is extensive.

Potential complications associated with RCT can be due to abnormal endodontic morphology, but are more frequently associated with poor technique and inadequate instrumentation. It is essential that any VNs involved in surgical endodontic procedures are knowledgeable about the potential complications to assist in their prevention where possible, or understand how they can further aid the VS should a complication arise. The key reasons for the development of complications are summarised in Table 2.

| Abnormal morphology | Poor technique Inadequate instrumentation |

|---|---|

| Irregular root morphology | Gouging the opposite dentinal wall when creating the access point |

| Lateral canals | Crown perforation — in addition to gouging, all layers of the opposite tooth wall are perforated |

| Pulpal stones | Instrument fracture — files susceptible if not used carefully |

| Occluded canals | Pulpal floor perforation — another complication associated with access point creation |

| Stenosed canals | Haemorrhage — usually indicative that there is remaining pulp tissue or there is a perforation |

| Open apex | Lateral wall perforations — overzealous file use |

| Fractured roots | Hedging — files are misdirected due to the access point not running smoothly into the pulp chamber |

| Ledging – occurs if files are used that are shorter than the working length of the canal |

Role of the VN during endodontic procedures

It is clear that performing RCT is a time-consuming and specialist procedure, which is why the VS needs a competent and knowledgeable VN to assist her/him during the procedure (Sylvester, 2005). Knowledge leads to anticipation of the next step of the procedure making it more efficient overall, which ultimately reduces the length of the patient's general anaesthetic.

The VN must be knowledgeable about the positioning for radiographic exposures and the development of films if digital radiography is not used, and they must be able to identify and appropriately prepare all of the required materials and instrumentation prior to the procedure. During the procedure the VN is expected to supply the VS with the equipment they need during each stage of the RCT, remove used equipment, know when the VS requires suction during canal flushing, understand how to prepare different materials as many of them need mixing prior to use, in an effort to ensure the VS does not lose concentration at any point. Post procedure, the VN must know how to clean the equipment properly and prepare it for sterilisation. Much of the equipment used is very specialised and subsequently expensive, so knowledge relating to the care and maintenance of such equipment is vital (Sylvester, 2005).

The VN will often be heavily involved in the after care of the patients, both in the immediate recovery period and into the future, providing the owners and pets with dental clinic appointments for monitoring and homecare advice. Education is key to maintaining oral health, and early intervention from an endodontic perspective can result in the retention of more teeth. Owners must be encouraged to regularly assess their pet's teeth to identify problems at home. Ultimately the VN assisting with advanced dental procedures is an asset to the practice and an invaluable aide to the VS performing the procedure.

Conclusion

RCT is a feasible alternative to the extraction of peritodontally healthy, strategic mature teeth in dogs and cats. It is an advanced dental procedure, and as such should be performed by a specialist VS with the aid of an appropriately trained and knowledgeable VN. The thorough and appropriate assessment, diagnosis and creation of a treatment plan by the VS are crucial to the success of the procedure, and all equipment should be used correctly and be well maintained by the VN to facilitate a successful outcome. The benefits to the patient of RCT versus extraction of healthy teeth is well recognised by veterinary dental specialists, and as such referral for RCT should always be offered, where appropriate, to the owners of animals with affected dentition.