The equine neonatal period is considered to be the first 4 weeks postpartum (Adams et al, 2011). During this neonatal period equine patients require specific and intensive nursing care which, although tiring and time consuming, is extremely rewarding when successful.

Equine neonatal care has progressed over the last 30 years which has led to a decrease in mortality and an increase in specialist facilities available worldwide (Austin, 2013). To provide nursing care to an equine neonate it is essential that veterinary nurses have specific knowledge, clinical experience and a comprehensive understanding of infection control.

Background information

The foal's immune system develops during fetal life so they are born immunogenically competent, but as the equine placenta does not allow transfer of immunoglobulins to the fetus, foals are born without circulating antibodies (Giguere and Polkes, 2005). The foal is born into an environment with countless pathogens so it is essential that they receive passive immunity from the colostrum (Giguere and Polkes, 2005).

Specialised intestinal epithelial cells in the neonate allow absorption of maternal immunoglobulins from the mare's colostrum; the absorption capacity of these cells rapidly declines reaching less than 1% 20 hours postpartum (Austin, 2013). If the foal has not received or has not absorbed the immunoglobulins this is known as failure of passive transfer (FPT) (Gigure and Polkes, 2005; Austin, 2013). Foals with FPT are at a very high risk of sepsis so infection control is of paramount importance when providing nursing care.

The specialised epithelial cells in the equine neonate's intestine are non-selective meaning that anything that is ingested by the foal could easily enter systemic circulation (Austin, 2013). When dealing with neonates veterinary nurses should have infection control at the forefront of the mind at all times.

Testing immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels

To determine if passive transfer has occurred the equine neonate's serum IgG concentration can be tested. Commercial test kits are available and provide quick and accurate results (Austin, 2013).

If the IgG levels are less than 8 g/litre and the foal is less than 24 hours old then colostrum can be provided enterally, via a nasogastric tube or bottle (Knottenbelt et al, 2004). If the equine neonate is more than 24 hours of age the specialised epithelial cells within the small intestine will have closed down and passive transfer will not occur (Austin, 2013). In these cases hyperimmune plasma can be administered intravenously; this delivers immunoglobulins directly into the circulatory system providing the equine neonate with protection from pathogens (Knottenbelt et al, 2004).

Ideally the IgG concentration of the mare's colostrum should be measured prior to the foal suckling and should have a mean concentration of at least 50 g/litre (Knottenbelt et al, 2004). This can be done by clients using simple commercial test kits. Mare's that are in poor health are more likely to produce colostrum with lower IgG concentrations, so foals should be carefully monitored during the neonatal period (Austin, 2013).

Accommodation

To decrease the infection risk neonates should be stabled away from other patients. O'Dwyer (2013) suggests that the infection risk of all patients should be assessed on admission. This would be of benefit if it was not possible to fully separate the equine neonate from the other patients as they could be housed with the lowest risk patients closest.

Ideally one or two members of the nursing team should be dedicated to the care of the equine neonatal patient to further reduce the infection risk that is posed by the other patients (Monsey and Devaney, 2011).

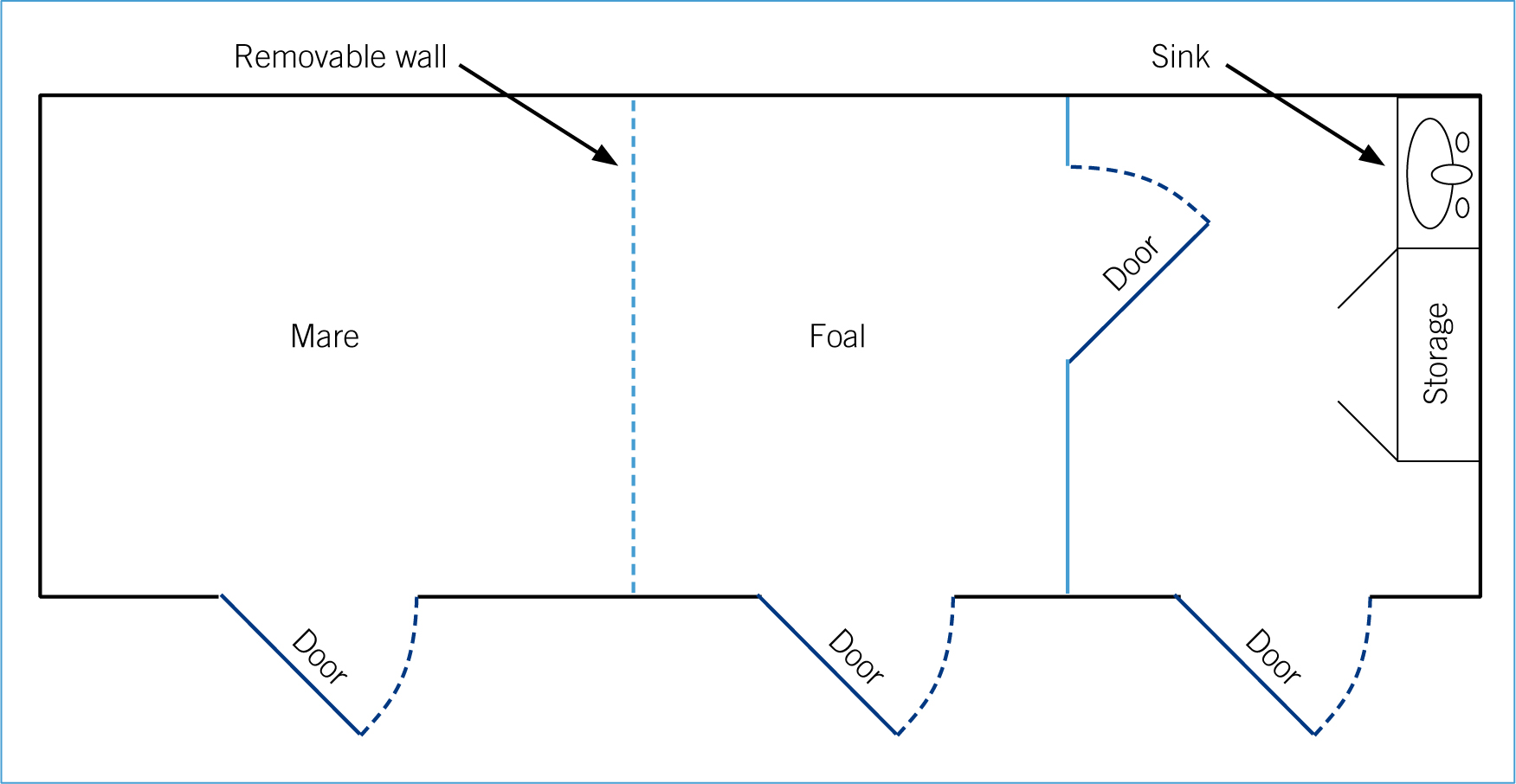

The accommodation should have facilities including separate equipment, personal protective equipment (PPE), storage area and a sink (Figure 1) (Monsey and Devaney, 2011; Mallicote et al, 2012). The neonate stable should be free from draughts as equine neonates' ability to thermoregulate is poor

Separating the mare from the foal

If the mare and foal are to be separated the mare should be positioned so that she can see the foal, this will reduce the stress levels of both the mare and the foal and increase the likelihood that the mare will allow the foal to nurse again when it is able to (Greet, 2008). If dealing with a pony mare and foal it is useful to have a barrier with removable sections so that the height can be adjusted to the requirements of the mare (Figure 1).

From an infection control point of view the mare should be viewed as a potential source of contamination and clear protocols, such as hand washing after handling the mare, should be in place to minimise the risk of spreading infection.

Umbilical care

There are several potential routes by which pathogens can be transmitted to an equine neonate, these include; the gastrointestinal tract; the respiratory tract; and the umbilicus (Adams et al, 2011). The majority of equine neonatal infections are caused by bacteria, although viral infections are also prevalent, and due to the immature nature of the equine neonate's immune system it is essential to minimise the risk of pathogen transmission (Adams et al, 2011). Measures such as thoroughly disinfecting the accommodation between patients and maintaining a high standard of hygiene throughout the hospitalisation period are of paramount importance (Helps et al, 2011).

As the umbilicus is a potential route for pathogens to enter systemic circulation it is essential to apply antiseptic solution at regular intervals. Knottenbelt et al (2004) recommends that a solution consisting of 60 ml of surgical spirit and 500 ml of 0.5% chlorhexidine should be applied to the umbilicus every 6–8 hours for the first 24 hours. It is also suggested that the use of a spray may be more effective than dipping the umbilicus due to the fact that the solution will be under pressure (Knottenbelt et al, 2004). This can be achieved by drawing the solution up into a 50 ml syringe and spraying it on to the umbilicus. Care should be taken not to get the neonate too wet as their ability to thermoregulate is poor and this may result in hypothermia (Austin, 2013).

Equipment

Transmission of pathogens via fomites is a significant risk to the equine neonatal patient; separate equipment that is either new or has been sterilised should be used to reduce this risk (Mallicote et al, 2012). Feeding equipment such as bottles, funnels and measuring jugs should be sterilised between every use and any unused milk should be stored in a refrigerator or disposed of appropriately. If there is more than one equine neonate hospitalised, a colour coding system could be put in place to avoid confusion over which equipment should be used on which patient.

Barrier nursing

Strict isolation and barrier nursing protocols should be put in place when nursing the equine neonate to prevent nosocomial infections. The use of foot dips containing a suitable disinfectant solution and alcohol hand rubs is essential (Monsey and Devaney, 2011). Quaternary ammonia disinfectants, such as Anigene® (Medimark scientific), are effective against most pathogens so would be appropriate for use in the foot bath and to disinfect the accommodation (Mallicote et al, 2012).

When using alcohol hand rubs veterinary staff should use a methodical technique and make sure that all areas of the hands including the finger tips and thumbs are included (Vincent, 2012). The Word Health Organisation (WHO) hand hygiene method can be used to ensure that all aspects of the hands have been coated in the alcohol hand rub.

It may also be necessary to use PPE, such as gloves and overalls, as additional biosecurity precautions. The use of overalls would be advisable if it is not possible to have a dedicated neonatal nurse as clothing is a potential source of contamination (Knottenbelt et al, 2004). If wearing gloves to carry out nursing interventions they must be removed before touching any other items, such as the hospital records, to prevent contamination (Shea and Shaw, 2012).

In human neonatal nursing high levels of training and nursing excellence have been shown to reduce the risk of mortality due to nosocomial infection (Gallagher, 2013). Some of the protocols which are seen as standard in human neonatal nursing would be beneficial if they were adopted by veterinary nurses. An example of this would be the use of alcohol hand rubs between nursing care intervention rather than just between patients. Research in the human nursing neonatal field has shown that even activities considered as being clean care activities, such as bottle feeding a neonate, significantly increase the bacterial colonisation of the nursing staff's hands (Iijima and Ohzeki, 2006). This is something that would not be difficult to implement in an equine hospital environment.

Designing infection control protocols

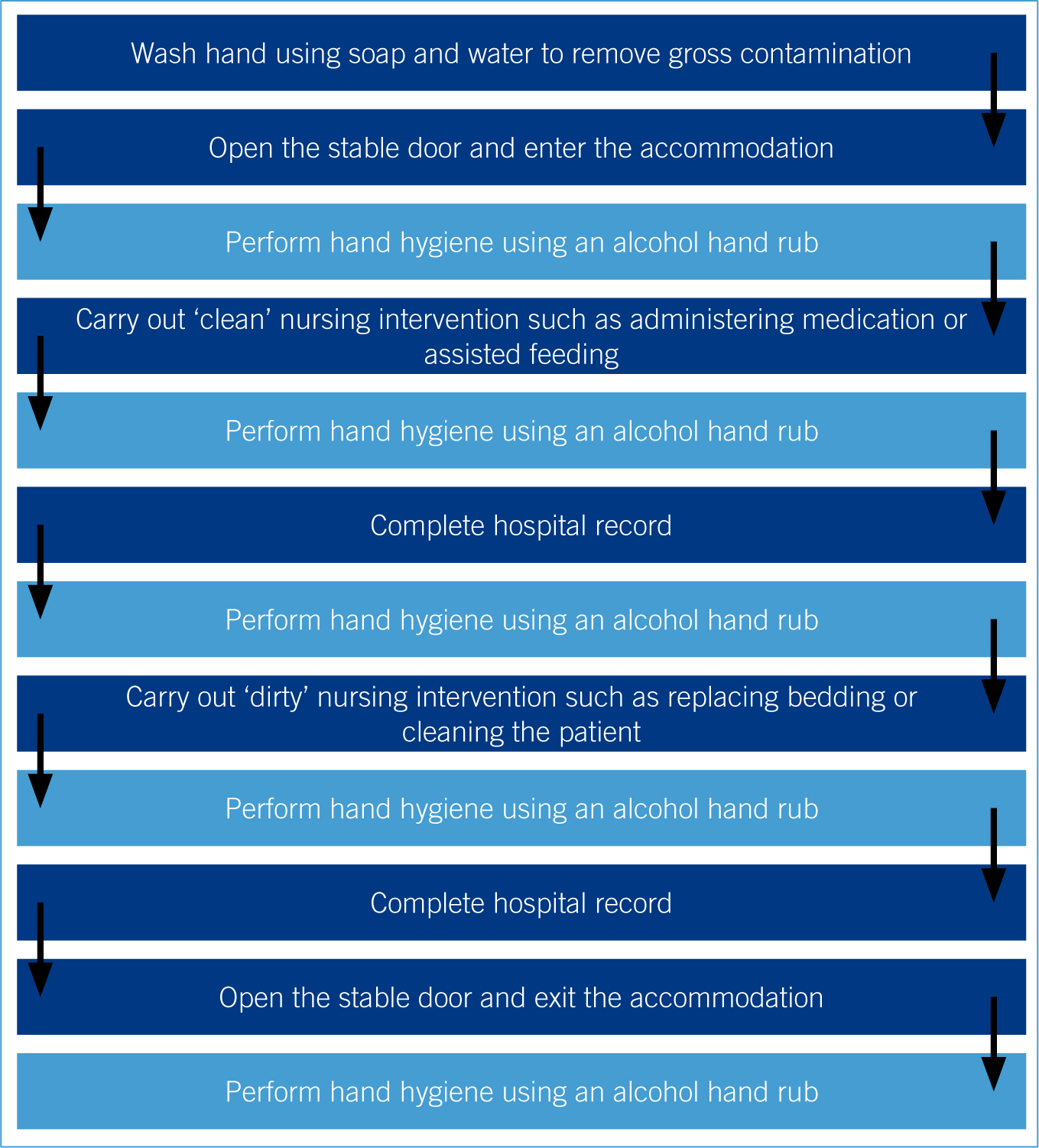

When designing equine neonatal infection control protocols it is essential to consider practicalities such as the position of the alcohol hand rub dispenser. If hand hygiene is performed before opening the stable door the veterinary nurse would contaminate their hands before commencing the nursing care activities. In the human field strict protocols such as opening the incubator with an elbow are in place to prevent such contamination (Belton, 2007).

In an equine hospital the alcohol hand rub dispenser could be placed inside the stable so that the veterinary nurse can open the door before performing the hand hygiene protocol to prevent contamination of the hands from the stable door (Figure 2 for suggested protocol). Alternatively a mechanism that could be used to open the stable door without using the hands could be developed and similar protocols to the one described by Belton (2007) could be implemented.

It is also necessary to develop protocols for a hospitalised equine neonate when the mare is the primary patient as it is essential that the needs of the neonate are met and that strict barrier nursing protocols are implemented (Mallicote et al, 2012).

Improving compliance with infection control protocols

Hand hygiene is the most important biosecurity measure to prevent nosocomial infections and a study in a human neonatal ward shows that the education of staff and setting and reviewing of clear step-by-step protocols significantly improves staff compliance (Lam and Lee, 2004). The study also looked at the use of alcohol hand rubs in comparison to the use of soap and water and found that increased compliance was seen when alcohol rubs were provided (Barbara et al, 2004).

In equine hospitals the reviewing of protocols and increase in staff education could be implemented to improve compliance with infection control protocols this would reduce the risk of nosocomial infections. The changing of protocols and the introduction of new concepts should be approached sensitively by veterinary practices as apprehension relating to change in approach to nursing care has been seen (Girotti, 2011).

When nursing an equine neonate, communication and effective hand over between the nursing team is essential to ensure that infection control protocols are followed and the nursing care provided is of a consistent quality (Gray and Clarke, 2011). When a case is handed over the nursing team should take the opportunity to reflect on the nursing care that has been provided and adjust the planned nursing care interventions as necessary.

Reflective practice

Reflection can be used to develop critical thinking which is essential for professional advancement and the development of clinical skills and protocols (O'Connor, 2008). When updating neonatal infection control protocols a reflective approach should be taken so that key adjustments can be made to reduce the risk of the transmission of pathogens to patients from nursing staff's hands or from other patients.

In order to reflect on the provision of nursing care detailed clinical records are required which could be in the form of a nursing care plan (Wager and Welsh, 2013). O'Connor (2008) suggests that reflective practice requires guidance and structure so senior veterinary nurses should support and provide guidance to their team to encourage them to reflect on the nursing care that they have provided.

Protocols should be under constant review and all members of the team should be asked to reflect on the care they have provided so that trends can be recognised and protocols can be adjusted and updated in line with evidence-based practice (O'Connor, 2008).

Conclusion

Infection control protocols such as the strategic use of alcohol hand rubs should be implemented when nursing an equine neonatal patient to improve the biosecurity. When developing new protocols some key points could be adapted from human neonatal nursing practice and to enhance equine hospital protocols. All members of the nursing team should be encouraged to reflect on the nursing care that they have provided to enable evidence-based advancements in clinical practice which will improve the quality of patient care.