Pain assessment in animals is challenging, because as non-verbal patients, animals are dependent on veterinary professionals to identify their pain. Managing pain in surgical patients is an integral part of patient care, and unmanaged pain can have a detrimental effect on recovery and wellbeing (Cambridge et al, 2000; Hellyer et al, 2007). Although surgical procedures in dogs and cats are considered to be equally painful, cats have historically received analgesia less often in the post-operative period (Lascelles et al, 1999). One of the main reasons for the disparity in treatment between species is the difficulty in recognising and assessing pain in cats (Capner et al, 1999).

Lascelles et al (1999) found that 71% of veterinary surgeons delegated the task of post-operative monitoring to veterinary nurses, but 68% of them felt nurses had insufficient knowledge of pain and analgesia. In another study, 96% of veterinary nurses also felt their knowledge of pain management could be improved. Most agreed that a pain scoring system was a useful clinical tool, yet only 8.1% of the practices in this study were using a formal pain scoring system (Coleman et al, 2007). It is clear that veterinary nurses have a significant role to play in identifying acute pain in surgical patients and are integral for effective pain management.

Recognising pain

Cats tend to hide pain as a protective mechanism and as a result their behaviour in response to pain is more subtle than in other species such as dogs (Capner et al, 1999). In addition, cats will often mask pain responses in a stressful environment, and it is difficult to distinguish between anxiety, stress and pain. It is important to appreciate that lack of outward expression does not necessarily indicate that the animal is not experiencing pain (Flecknell, 2000; Rochlitz, 2000; Lindley, 2011). An understanding of the species and where possible the individual's normal behaviour, is essential in order to recognise any changes in behaviour and appreciate the cause (Hellyer et al, 2007; Lindley, 2011). In the recovery period, surgical patients should be observed for changes in their normal behaviour, in addition to the development of abnormal behaviour, reaction to touch and physiological parameters (Table 1). Behavioural changes indicative of pain and sometimes stress include the reduction of normal behaviour such as grooming, appetite and ambulation. General reduced activity, interaction with the environment and a lethargic attitude has also been reported to be indicative of pain in cats (Väisänen et al, 2007). Changes in normal behaviour may be accompanied by the development of abnormal behaviour in the individual (such as aggression in an otherwise unaggressive cat), or abnormal for the species (such as over grooming or attacking a painful body area).

Table 1. Indicators of acute post-operative pain in the cat

| Changes in normal behaviour | Abnormal behaviour | Reaction to touch and wound palpation | Physiological parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reduced activityAnorexiaDecreased ambulationLethargic attitudeReduced interaction with environmentDecreased grooming | Aggression (increased or decreased)Inappropriate eliminationLooking, licking or aggression towards a painful areaRestlessnessHiding or escape behaviourOver groomingVocalisation by groaning, growling or purringExcessive tail waggingContracting limbs or abdominal muscles | FlinchingTwitchingVocalisationBody withdrawalHead turningIncreased bodytensionAggression | TachycardiaTachypnoeaHypertension or hypotensionPyrexiaMydriasis |

In a clinical situation, it is important to consider causes of unintentional pain and discomfort which may be overlooked. For example, discomfort associated with hospitalisation for surgical procedures includes: intravenous catheterisation; limb, neck or abdominal dressings; examinations and palpation of painful or non-painful areas; restraint; and body positioning under anaesthesia. In addition, the level of pain associated with a surgical procedure can be anticipated to some degree, but the magnitude of the painful stimulus does not necessarily correlate with the response produced (Hellyer et al, 2007). Similarly, patients undergoing the same surgical procedure may have different requirements for analgesic agents; when given the same analgesic protocol, some patients may experience adequate pain relief and others require additional analgesia (Robertson, 2008). This emphasises the need for careful observation, assessment and an individual approach to pain management, as one analgesic protocol is unlikely to suit all patients and should be tailored accordingly.

Behaviour indicative of acute pain

Behavioural responses to pain are complex, and individuals will exhibit a range of pain behaviour (Table 1). Specific body postures have also been demonstrated to indicate pain, and serve as protection against movement-induced pain. A ‘hunched’ or ‘tucked-up’ posture in cats may indicate abdominal pain (Figure 1) (Waran et al, 2007). A cat exhibiting this posture will be in sternal recumbency, weight bearing on forelimbs, often with the head lower than the body. They are reluctant to move, maintaining a statue-like appearance with visible muscle tension, particularly in the abdomen.

Another posture anecdotally associated with abdominal or musculoskeletal pain is a cat in lateral recumbency, with the pelvic limbs contracted or extended, sometimes held in one position for periods of time (Figure 2).

Pain assessment

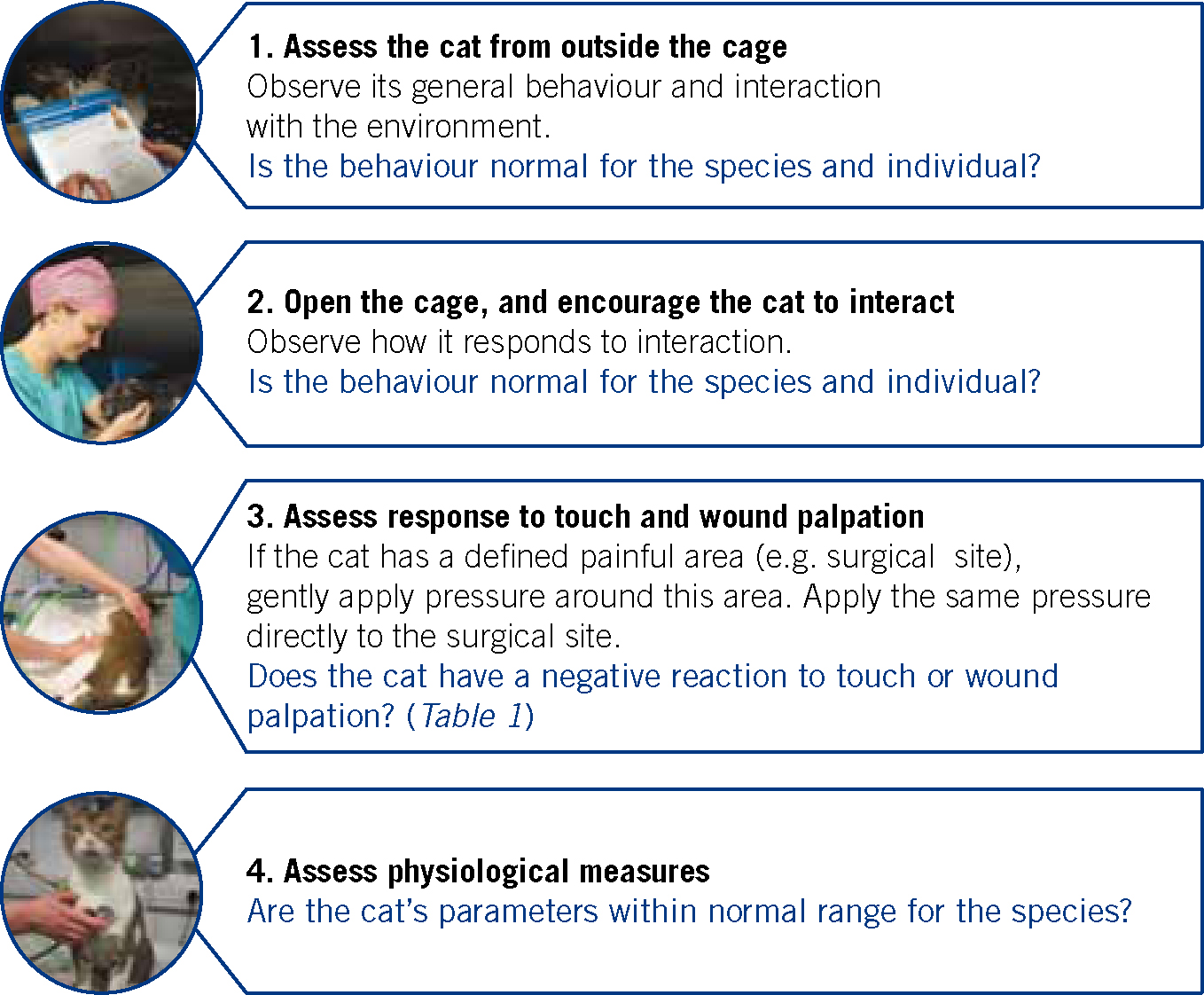

Pain is a sensory and emotional experience, and so it is important that pain assessment incorporates the physical intensity of the pain, as well as the emotional impact of that pain on the individual (Murrell, 2013). Currently, pain assessment relies predominantly on behavioural observation and basic clinical evaluation, which are used together in ‘cage-side’ judgements of the patient, or more formally in a scoring system. Both these methods of assessment should incorporate a non-interactive and interactive approach (Figure 3).

Scoring systems

Many parallels have been drawn between the development of scoring systems for human infants and animals, essentially because of the communication barrier between patient and carer (Flecknell, 2008). Pain scoring methods developed for non-verbal humans have been adapted and applied in animals and general pain scoring systems range from simple to complex. Simple scoring systems include the Simple Descriptive Scale (SDS), Numerical Rating Scale (NRS), and the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS). Complex scoring systems include multifactorial or composite pain scales, such as the Dynamic and Interactive Visual Analogue Scale (DIVAS). Studies exploring the use of behaviour as an indicator for acute post-operative pain have enabled the development of more reliable, species-specific, pain scoring systems (Holton et al, 2001; Brondani et al, 2011), and although they have yet to be validated in cats, they encourage frequent evaluations of patients, document trends and assist in standardising methods of assessment in clinical practice (Robertson, 2010).

Feline scoring systems

The Colorado State University developed the first DIVAS to assess feline acute pain (http://petslastwishes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/felinepainscaleC-SU.pdf). Similar to the Glasgow Composite Measure Pain Score (GCMPS) used in dogs, this scoring system overcame the limitations of one-dimensional observational assessment for cats, which show less overt expressions of pain as a protective response in the presence of an observer (Robertson, 2010). This scale has proved effective at detecting differences between treatment groups in cats following ovariohysterectomy (Lascelles et al, 1995; Slingsby and Waterman Pearson, 1998). The Colorado scale requires minimal interpretation, and incorporates physiological and behavioural assessments, as well as response to wound palpation and general body tension (Muir and Gaynor, 2002).

One pharmaceutical company in the UK (Alstoe Animal Health) has developed the Vetergesic® Multidimensional Composite Pain Scale for acute post-operative assessment in cats (http://www.vetclick.com/downloads/Cat%20pain%20Chart_v5.pdf). It includes non-interactive and interactive assessments with focus on the cat's behaviour. It requires minimal interpretation and each factor (e.g. posture, comfort and response to wound palpation) is sub-scored allowing the observer to evaluate them separately.

The UNESP-Botucatu Multidimensional Composite Pain Scale for assessment of acute post-operative pain in cats has been developed and undergone initial validation by Brondani et al (2011) (http://animal-pain.com.br/assets/upload/escala-en-us.pdf). This scale assesses a multitude of factors including posture, comfort, activity, vocalisation, surgical wound palpation reaction, and appetite. Initial validation, and has shown the scale is able to detect differences between analgesic treatment groups in cats undergoing ovariohysterectomy. The scale requires some interpretation, but encourages the assessor to develop their pain assessment knowledge and application through the use visual aids and self assessment (http://animalpain.com.br/en-us/escala-multidi-mensional.php).

Practical pain scoring

Scoring systems used in clinical practice currently serve as a tool for identifying and recording behavioural and physiological indicators of pain, in addition to standardising methods of assessment. Certainly the use of any formalised scoring system is better than none, because it allows veterinary nurses to record each patient's pain response over time, so analgesic interventions can be evaluated. Ideally the scoring system used should be valid, reliable and sensitive, but also user friendly, readily used and become an integral aspect of a practice's post-operative care management. Veterinary practices should select a scoring system that suits their specific needs, but consider staff limitations, time constraints and training required (Robertson, 2010).

- To answer the CPD questions on this article visit www.theveterinarynurse.com and enter your own personal login.

Ideally patients would be continuously observed, with occasional interactive observations following a surgical procedure, unfortunately this is not practical in a busy veterinary practice. Providing the patient's recovery was normal, they should be assessed for pain hourly for the first 4–6 hours. Patients should be allowed to sleep, and generally they should not be woken up for pain assessments (Robertson, 2010). The American Animal Hospital Association and the American Association of Feline Practitioners (AAHA/AAFP) has produced an algorithm to assist veterinarians with pain management decisions for their patients (https://www.aahanet.org/PublicDocuments/PainMngtAlgorithm-web.pdf) (Hellyer et al, 2007).

Implementing pain scoring in clinical practice

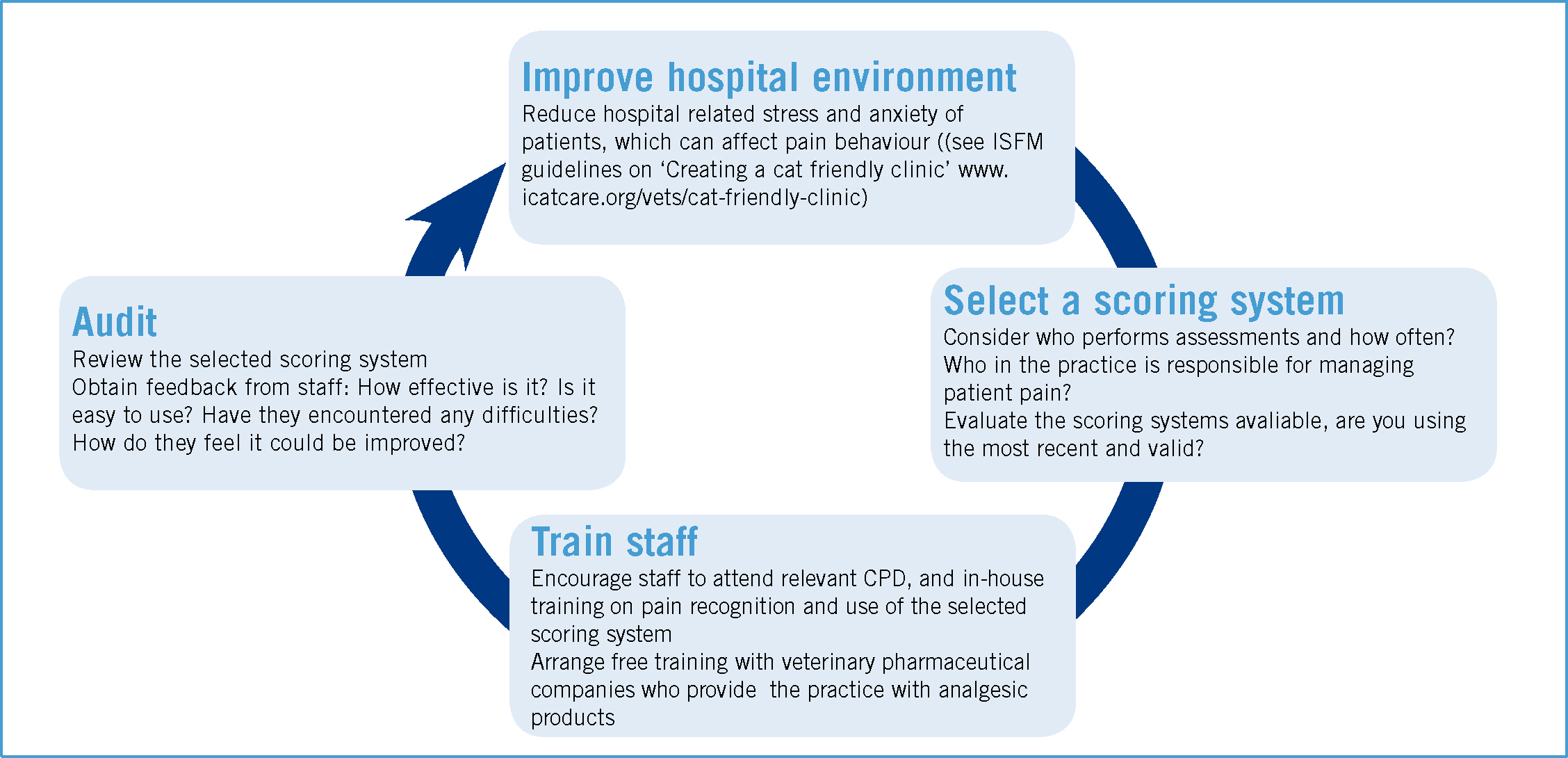

There are many advantages to using a pain scoring system within a practice, other than improving patient wellbeing. Implementing a scoring system can also have a positive impact on staff and the veterinary practice. Encouraging staff to improve their understanding of pain through professional development, and continual patient assessment will generate more knowledgeable, dedicated and principled carers, thus encouraging job satisfaction and teamwork. Regular clinical auditing of analgesic protocols ensures pain assessment is refined to suit the patient and practice's requirements (Hellyer et al, 2007). Figure 4 shows a framework for implementing a pain scoring system and auditing the use of an existing scoring system in a practice.

Conclusion

Pain recognition and assessment has an impact on the standard of patient care, and it is fundamental to providing effective pain management. Pain management in the cat is challenging, and barriers to reliable assessment in a clinical situation remain a problem. Formal scoring systems are a useful clinical tool to assist veterinary professionals, however they cannot replace intuition and should be used to enhance and support clinical judgement along with existing knowledge and experience of pain in veterinary patients. Although the veterinary profession's understanding of pain recognition and assessment is improving, it is evident that further research to validate scoring systems and key behavioural indicators of pain in cats, in addition to training for primary carers, would be advantageous for practical pain assessment and the provision of optimal patient care.

Key points

- Recognising pain in non-verbal patients is challenging.

- Managing pain in surgical patients is an integral part of patient care, and unmanaged pain can have a detrimental effect on recovery and wellbeing.

- Pain assessment using a multidimensional approach should include interactive and non-interactive evaluations, focusing on behavioural responses.

- Scoring systems encourage frequent evaluations of patients, document trends and standardise methods of assessment in clinical practice.

- Formal pain scoring is a useful clinical tool, used to enhance and support clinical judgement.