Presently, nursing staff in veterinary hospital wards often monitor their patients through measurements of simple variables such as temperature, respiratory rate, and heart rate through intermittent observations. According to Aldridge and O'Dwyer (2013) the ability to quickly and accurately detect clinical deterioration in a patient during these assessments is an essential nursing skill set for safe, quality care and for improving patient outcomes. Therefore, nurses should not only be able to detect subtle changes of early deterioration, but should also respond timely and appropriately.

Monitoring the patient

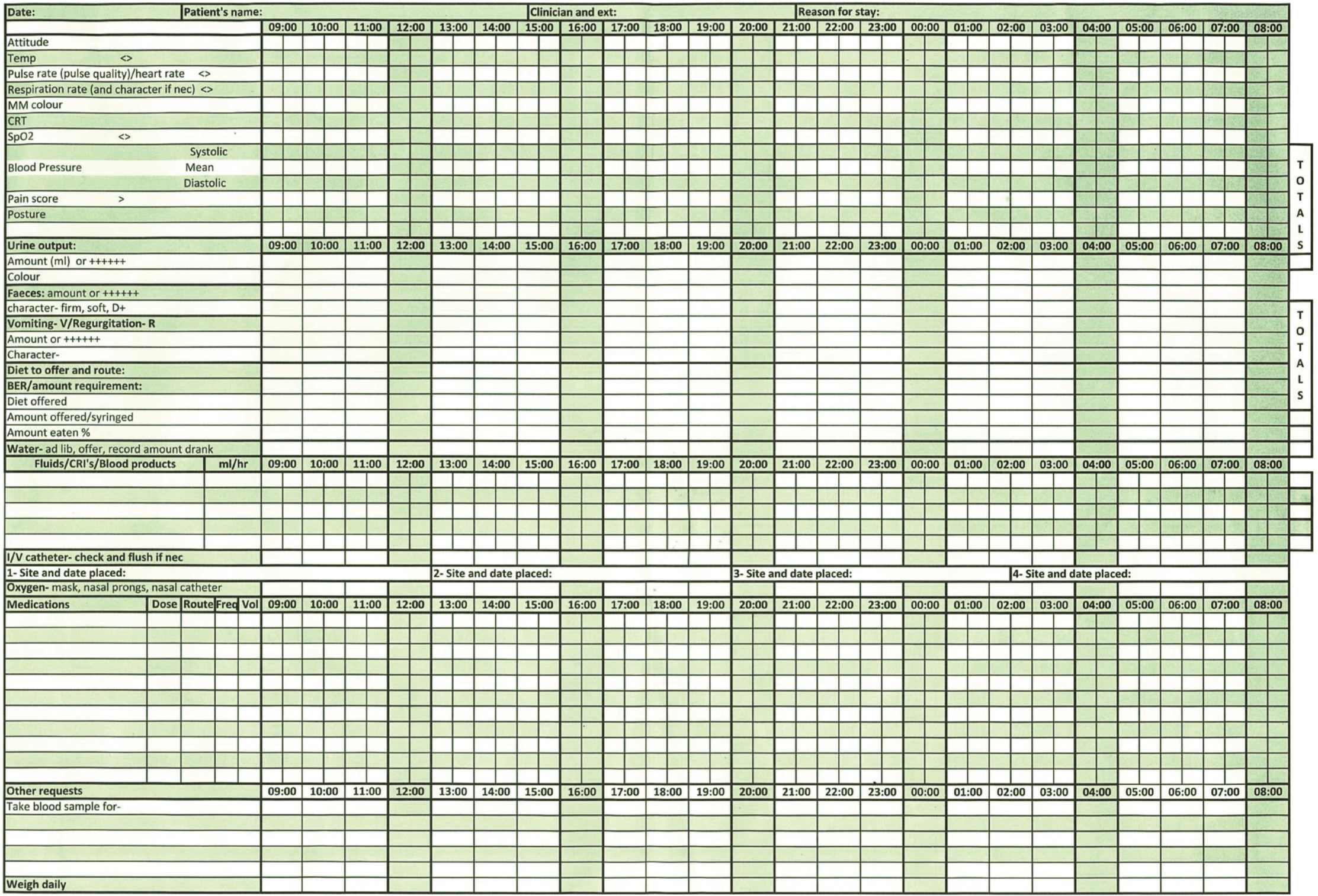

Close monitoring is vital to recognising changes that are indicative of patient deterioration. It allows time for intervention to avert an impending crisis. Instead of using a single one-off measurement, observing a ‘pattern’ in the monitored vital sign gives the most relevant information (Aldridge and O'Dwyer, 2013). It is essential to accurately record these findings in order to easily monitor an ongoing trend (see Figure 1). The possible complications, the individual patient, the perceived risk of deterioration, and the severity of the problem, which can all be documented on the animal's treatment plan, will determine the rate at which these parameters are monitored (Humm and Kellett-Gregory, 2016). Rather than performing more complex tests that require a longer time to complete, it should be noted that repeated re-examination of some important ‘basic’ parameters may be more effective in identifying early deterioration (Aldridge and O'Dwyer, 2013). More specific monitoring, such as lactate levels, blood gases, clotting times, and electrocardiography can be conducted when specific problems are observed through physical examination.

Preliminary or general assessment

A preliminary or general assessment of the patient and their environment should be performed by the registered veterinary nurse (RVN) before the nursing assessment is carried out. Nurses should take into consideration hand hygiene and the need for any personal protective equipment, such as gloves and apron, accordingly. On approach, the RVN should listen for any laboured respirations or abnormal breathing sounds, as well as observe the mentation, behaviour, posture, body condition of the patient (Ettinger et al, 2017) (Figure 2). Furthermore, the general health status of the patient may be ascertained through the presence of any equipment around them, such as oxygen delivery systems, infusion pumps (Figure 3), urinary collection bags and mobility aids.

Major body systems assessment — monitoring without monitors

While monitoring needs to be structured according to each patient, there are some parameters that need to be frequently recorded irrespective of the condition of the patient (Table 1). To identify even the smallest deviations, it should be emphasised that the RVN must be knowledgeable of the physiological parameters of the different species under their care.

Table 1. Mucous membrane (MM) colour and its possible significance

| MM colour | Possible significance |

|---|---|

| Yellow | Liver diseaseHaemolysis |

| Pale/white | Blood lossAnaemiaShock |

| Brick red | SepsisHyperthermia |

| Blue | Severe hypoxaemia |

The ABCD was suggested by Aldridge and O'Dwyer (2013) as a useful approach for examining major body systems, where:

- A = airway

- B = breathing

- C = circulation

- D = dysfunction of the central nervous system (CNS).

With this approach, nurses can systematically and holistically assess deteriorating patients.

A and B: respiratory system

As earlier stated, nurses should assess the respiratory system of the patient as they approach them by noting their respiratory pattern and effort, as well as their posture and observing whether airway sounds are clearly audible. Under normal conditions in dogs and cats, the abdomen and chest wall move in and out simultaneously, ventilation requires very little chest movement, and the respiratory rate is approximately 15–30 breaths per minute (Farry and Norkus, 2019). If the patient's effort in breathing is abnormal, this should be recorded alongside the rate. Bradypnoea occurs when the rate is less than normal, which may be affiliated with drug toxicity, especially opioids, or head injury. On the other hand, tachypnoea is the condition that occurs when the rate is over 30 breaths per minute, which may be caused by shock, thoracic trauma, or reduction of oxygen in the blood (hypoxaemia), and may also be linked with a non-respiratory sources such as metabolic acidosis, traumatic brain injury, increased body temperature, stress, or pain (Peruski et al, 2017). In human medicine literature, tachypnoea is clearly documented as a discrete and early sign of deterioration, which often appears first before changes in other significant signs (Badawy et al, 2017).

Pulmonary auscultation is an important part of an assessment of the respiratory system and forms part of a holistic assessment which must be viewed alongside direct observation of the patient's breathing. A stetho-scope should be used to auscultate the chest wall, systematically auscultating each area, comparing the same areas on the right side of the chest to the left. There are several breath sounds the RVN should be familiar with, but the main ones to be aware of in detecting early deterioration are reduced or absent breath sounds, wheezes and crackles.

Aldridge and O'Dwyer (2013) explained that breath sounds may be reduced or ab-sent where pleural disease exists (pleural effusion, pneumothorax). More commonly lower airway sound abnormalities that are likely to be detected are crackles, wheezes, or rales (abnormal clicking, bubbling, or rattling sounds). Crackles may indicate pulmonary oedema such as that resulting from fluid overload, whereas wheezes are the result of airway narrowing and may be as a result of any condition causing broncho-constriction such as inflammation or as a result of mucus accumulation (Farry and Norkus, 2019).

Box 1.Physical parameters that require assessment and re-assessment regularly

- Capillary refill time

- Mucous membrane colour

- Pulse quality

- Heart rate

- Bodyweight

- Rectal temperature

- Respiratory effort and rate

- Demeanour

- Chest auscultation

C: circulatory system

Palpation of an artery and auscultation of the heart should be used simultaneously to assess heart rate/pulse rate (Figure 4). Any pulse deficit (i.e. an audible heart beat without a palpable pulse) can be detected when this is done (Rondeau and McCommon, 2017). The pulse rate normally falls within the range of 140–200 beats per minute (bpm) in cats, 60–120 bpm in large dogs, and 70–120 bpm in small dogs (Hackett, 2014). A pulse rate that is abnormally low is referred to as bradycardia. It may be regarded as normal in athletic patients and during sleep, but may also be a product of hypothermia, increased intra-cranial pressure, electrolyte imbalances, and drug administration such as alpha-2 agonists and opioids (Hackett, 2014; Norkus, 2019). Brown and Mandell (2014) cautioned that severe bradycardia is capable of significantly reducing cardiac output, which can lead to cardiogenic shock.

Tachycardia refers to the case where a pulse rate is more than 220 bpm in cats and 180 bpm in dogs (Hackett, 2014). A sensitive and early sign of hypovolaemia is increased pulse rate, which serves as a compensatory means to increase cardiac output, even with a reduced stroke volume. If volume loss is responsible for tachycardia, the heart rate should return to normal once circulating volume is restored. It is important to consider other causes of tachycardia, for instance hypercapnia, hypoxaemia, fever or pain (Al-drich, 2007). Unlike dogs, it should be noted that the heart rate of a cat in shock is usually slower than normal and often in the range of 120–180 bpm (Tabor, 2016). Based on the recommendation of Hackett (2014), an electrocardiogram (ECG) should be used to confirm all pulse abnormalities.

Colour of the mucous membrane and capillary refill time

The mucous membranes are normally pink in colour. This colour changes to blue, brick red, white, pale (Figure 5) or yellow (Table 1) in a diseased state.

Capillary refill time (CRT) is not an indication of blood pressure, but rather an indicator of peripheral perfusion. CRT is a measure of how fast blood flows back to the capillary bed after being digitally compressed, for instance, on the gum. A prolonged CRT of more than 2 seconds is an indication of poor perfusion, which is a result of peripheral vasoconstriction. It is usually common among patients with cardiogenic and hypovolaemic shock (Campbell, 2011). Conversely, patients in hyperdynamic conditions, such as fluid overload or systemic inflammation, often have a CRT of less than 1 second (Hackett, 2014; Bloor, 2019).

Heart auscultation

A stethoscope will not only help identify the heart rate of a patient, but it provides other vital information regarding the character of heart sounds and rhythm, thus enabling a comprehensive summary of a patient's cardiovascular status to be established. Among severely ill patients, cardiac arrythmias are often discovered, and these could indicate a substantial cause of illness, and are generally more prevalent in those suffering from structural heart disease (Farry, 2012). Should an arrhythmia be identified, then an ECG is recommended (Farry, 2012).

Blood pressure monitoring

Accurate, regular monitoring of the patient's blood pressure allows the RVN to detect subtle variations that may otherwise go unnoticed. Although an elevated blood pressure (hypertension) is an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease, it is a falling or low systolic blood pressure (hypotension) that is most significant in the context of detecting early deterioration; Aldridge and O'Dwyer (2013) described hypotension as common among patients in the pre-arrest setting. Hypotension may indicate circulatory compromise as a result of sepsis or volume depletion, cardiac failure or cardiac rhythm disturbance as well as CNS depression (Steagall, 2015).

Blood pressure is reflective of appropriate cardiac output and perfusion to tissues; hypotension is usually taken to mean a systolic pressure below 90 mmHg. Maintaining a systolic blood pressure >80 mmHg or mean blood pressure >60 mmHg is essential for maintaining organ perfusion (Table 3). Blood pressure is most easily measured via indirect methods, such as using oscillometric (Figure 6), or Doppler units. It should be remembered that trends in blood pressure readings are more important than a one-time measurement in predicting and monitoring clinical deterioration.

Table 3. Normal blood pressure (BP) values in dogs and cats

| Systolic BP | Mean BP | Diastolic BP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dog | 90–140 mmHg | 60–100 mmHg | 50–80 mmHg |

| Cat | 80–140 mmHg | 60–100 mmHg | 55–75 mmHg |

D: dysfunction of the central nervous system

Donnelly and Lewis (2016) explained that a change in consciousness is a sign of patient deterioration and advise that nurses must be able to identify and respond to any changes quickly.

The aim is not to perform a full neurological examination but rather a swift assessment of the patient's level of consciousness (Table 4). Aldridge and O'Dwyer (2013) advised that observation should begin as soon as the patient is approached: posture, level of consciousness, and interaction or response to their surroundings should be noted. If the patient appears bright, alert and responsive, Hackett (2014) suggested that the overall neurological status of the patient can be deemed as normal. A patient that has a lessened interest in the environment, slowed reactions to stimulation such as touch and sound, and tends to sleep more than normal is referred to as obtunded. If a patient can only be aroused by a strong repeated stimulus such as pain, this is characterised as stuporous or semi-comatose and the patient is considered to have a severe impaired level of consciousness. A patient that cannot be aroused and is completely non responsive is referred to as comatose, and in this instance the patient will require immediate comprehensive assessment (Sammut, 2005; Donnelly and Lewis, 2016).

Table 4. Levels of consciousness

| Alert and responsive | Normal behaviour |

|---|---|

| Obtunded | The patient is awake but responds less to stimuli |

| Stuporous | The patient responds only to painful/noxious stimuli |

| Comatose | The patient is unconscious and does not response to any stimuli |

Other monitoring

Temperature

A rectal thermometer is widely used to provide a reading on a patient's core temperature because of its accuracy. From the reading(s) pyrexia can be established, this refers to an abnormally high body temperature which occurs as a result of the body temperature regulatory set point being increased, indicating that despite the fact that the body is still regulating the body temperature, an infection could be present. An example of one such temperature increase beyond the regulatory set-point is hyperthermia, which occurs as a result of excessive heat production, such as from the abnormal muscular contractions of an animal suffering from a seizure. The general rule is: if the patient's body temperature exceeds 40°C (104°F), then this is of concern and should be monitored, and if an individual's temperature exceeds 42°C (107°F) then there is a risk to life (Aldridge and O'Dwyer, 2013).

Hypothermia on the other hand relates to an unusually low body temperature; it is generally considered to be a body temperature of less than 37°C (<99°F) despite a specific number being unidentified as of yet (Armstrong et al, 2005). Factors that have been proved to induce or increase the risk of hypothermia include prolonged exposure to the cold, sepsis, disorders of the endocrine system and overdoses of drugs; low body temperature has also been linked with hypovolaemia (Lee, 2017). In order to confirm that hypovolaemia is not the cause, should a reading of 36°C or lower be obtained, then the patient should be completely reassessed.

In addition to this, should a patient display symptoms of infection, a senior colleague should be notified immediately, this is because a key symptom of sepsis is abnormal shifts in body temperature (Gray, 2017).

Bodyweight

On admission to the hospital, the patient should be weighed. Fluctuations in fluid balance as opposed to changes in body mass are responsible for daily weight alterations (Pachtinger, 2013). For instance, should a patient remain normally hydrated then only minor weight changes will be observable. A sudden increase, however, could indicate problems such as excess fluid accumulation for example in the third space such as pleural and abdominal effusions. If a patient should lose fluids or experience prolonged periods of dehydration, then it is likely that there will be temporary acute losses in weight (Hackett, 2014; Pachtinger, 2013).

Communication and escalation

All assessments should be recorded accurately by the RVN, any trends in vital signs should be noted and the findings clearly passed to relevant colleagues on the completion of the patient's assessment. It is essential that the RVN is aware of all of the above indicators of possible patient deterioration. In addition to this, it would be meaningless to record data about the patient such as their temperature, pulse and respiration if the RVN is unaware of whether or not these readings are within normal ranges. The RVN must be knowledgeable of the accepted ranges of these parameters in order to alert the veterinary surgeon should any of the readings be cause for alarm.

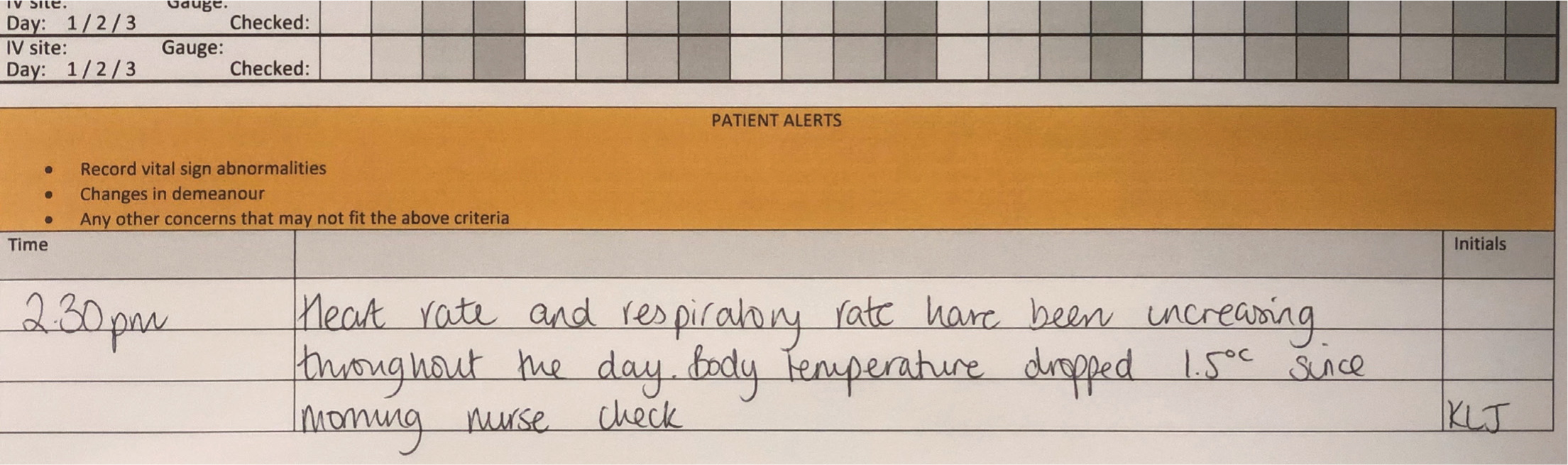

Concerns that do not require immediate remedy can be recorded on the daily hospitalisation chart, in a dedicated section that allows for quick and easy access to this information (Figure 7).

The role of intuition

While nursing patients that are in danger of clinical decline, the significance of the human senses, and the vital functions which they complete, cannot be exaggerated. This is demonstrated by the fact that the most crucial monitoring method is clinical assessment, which must be conducted using the RVN's senses. Should an excessive degree of importance be placed on data which is supplied by monitoring resources and an insufficient amount of awareness is fixed on the patient's physical examination, then there are often tragic outcomes (Farry, 2012). An experienced RVN will generally possess the instinct and capability of identifying alterations in the clinical condition of a patient, no matter how minor.

Conclusion

The swift identification of patients that are clinically declining is supported by a systematic patient examination, thus facilitating quick and successful responses to intervene, in which, each aspect of the response should be clearly understood by RVNs. RVNs should also understand the difference between normal and abnormal findings, they must then be able to associate these findings with the possible root causes and pathophysiology. Overall, efficient interaction and communication among the veterinary team is pivotal to saving a patient whose health is declining, failure to do so could have catastrophic outcomes.

KEY POINTS

- Consistent, reliable monitoring must be carried out regularly by the registered veterinary nurse (RVN) as this constitutes one of the fundamentals to the care of patients.

- In order to establish patients that are at a greater danger of clinical deterioration, a methodical approach should be employed, in which monitoring equipment does by no means substitute a detailed assessment of the patient.

- Irregular findings must be both identified and evaluated in the same manner as the other readings, and should the reading be of any concern, then the veterinary surgeon should be notified as soon as possible.