Cats and dogs are exposed to a wide range of parasites, such as Toxocara spp., Echinococcus granulosus, Angiostrongylus vasorum and tick-borne pathogens, which may cause significant disease in pets or present zoonotic risks to owners (Morgan et al, 2005; Overgauuw and Van Knapen 2013; Craig, 2014). Although there are little data on current UK disease incidence from these parasites, the consequences of infection are potentially severe. Some parasites with disease and zoonotic potential are ubiquitous and exposure is practically impossible to avoid. For UK cats and dogs this is true of the roundworm Toxocara and cat fleas. Regular treatment for Toxocara spp. and fleas is essential and should therefore form the basis of all cat and dog parasite control programmes. Other parasite prevention is risk assessed on the basis of lifestyle and geographical distribution. Parasites to consider in the UK would be ticks (Ixodes spp., Dermacentor reticulatus), tapeworm (Dipylidium caninum, Taenia spp., E. granulosus) and lungworm (A. vasorum).

Even where routine preventative treatments are used, diagnostic testing is useful in surveillance and monitoring of the effectiveness of parasite control programmes. Parasite diagnostics may be carried out on a variety of tissues and bodily secretions but the most commonly used to yield rapid diagnostic results are faeces and blood, as well as examination of the skin and coat.

Veterinary nurses are pivotal in providing advice on parasite control and they can also assist with diagnostic testing and sample collection via dedicated parasite control clinics, or when supporting the veterinary surgeon with consultations. This is an area where interested/dedicated veterinary nurses (RVNs) can excel and utilise a range of skills providing increased job satisfaction.

Parasite control clinics can be implemented in any practice, no matter the size or set up. When undertaking parasite control clinics consideration must be given to the room used. The ideal would be a dedicated nurse consultation room decorated with appropriate literature/posters, stocked with resources and training aids such as models/diagrams and prepared with suitable equipment to obtain samples for diagnostic testing. If not available any consultation room or private area could be utilised and the RVN could prepare a tray with equipment/resources which could be moved from room to room as required. Regardless of the type of space used it should be clean/presentable and barriers to communication should be minimised.

Depending on the practice set up, one or multiple RVNs may be responsible for running the clinic. The advice given and the tests/treatment options recommended should therefore be standardised across the team. The ideal RVN would be someone who is passionate about parasite control and who enjoys educating clients (Tottey, 2015). Consideration should be given to whether the consulting RVNs should undertake the suitably qualified person (SQP) qualification with AMTRA or VetSkill. Holders of the SQP qualification for companion animals (C-SQP) can prescribe and dispense POM-VPS and NFA-VPS anthelmintics, negating the need for a consultation with a veterinary surgeon prior to supplying a product, which can be beneficial (Ackerman, 2012). Preventative and treatment products for Angiostrongylus vasorum are POM-V and therefore need the involvement of a veterinary surgeon.

The RVN(s) running the clinic must be aware of his/her own consulting style — use of communication models, consulting models such as the Cambridge-Calgary model (Ackerman, 2012) and an awareness of the 7Cs of communication can aid in developing this (Hedberg, 2016). To maximise compliance communication should be tailored to the client and a range of methods used to cater for differing learning styles.

The diagnostic tests that can be used and the RVNs role in the application of these tests is detailed in this article. For further information on the parasites discussed and how to run effective parasite control clinics/tailor communication, the reader is directed to previous articles written by the authors (Richmond et al, 2017, Wright 2017).

Faecal testing for worms

Coproantigen or faecal flotation can be used as an alternative to routine preventative treatment for intestinal nematodes as long as testing is carried out at least four times a year and the client understands that shedding of zoonotic life stages may take place in-between testing. Testing alongside treatment is extremely useful, however, as it demonstrates good efficacy and compliance, while also allowing early detection of treatment failure.

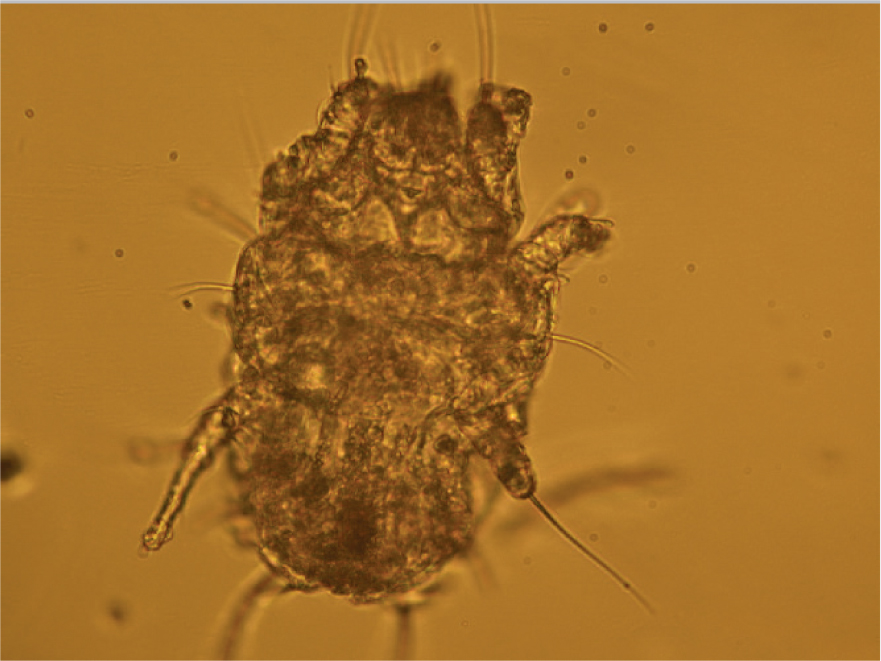

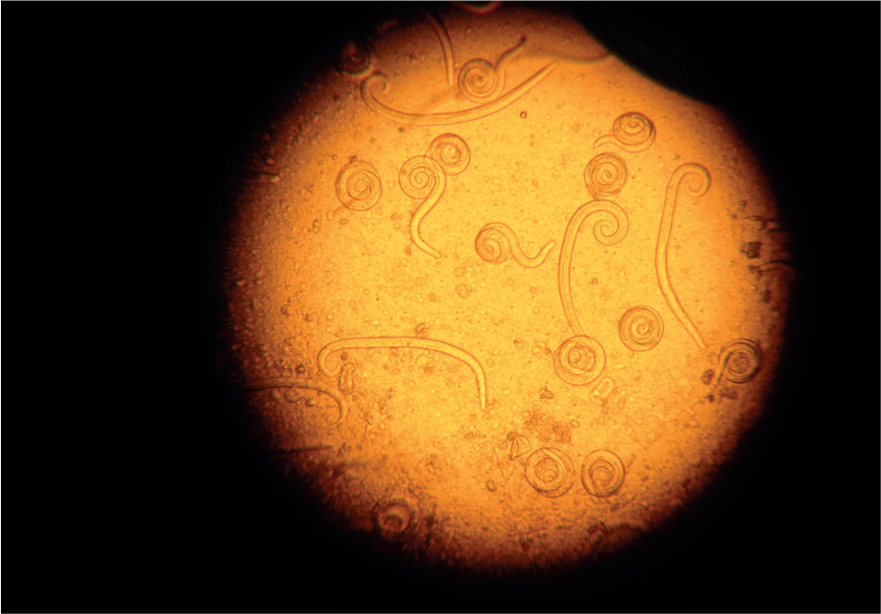

Many parasites intermittently pass ova, cysts or larvae in the faeces which can then be detected by faecal analysis. Shedding of larvae and ova is often intermittent so ideally samples should be collected over 3 consecutive days for increased diagnostic sensitivity. If the sample is collected by the client, it must be picked up as soon as it is passed. If left on the ground, faeces rapidly become contaminated with free living nematodes (Figure 1) and mites (Figure 2). These may be confused with parasitic life stages and will also obscure the field of view during microscopic examination if present in large numbers. Once collected, samples should either be examined immediately or stored at 4°C to prevent hatching of ova or larval development. Hookworm eggs will rapidly larvate and hatch if faeces are left at room temperature. The RVN can play a role in educating clients on sample collection and storage methods that facilitate preservation of the sample, but also good hygiene, minimising exposure to the client.

Faeces can be examined for parasite ova and larvae by the following methods.

Direct smear

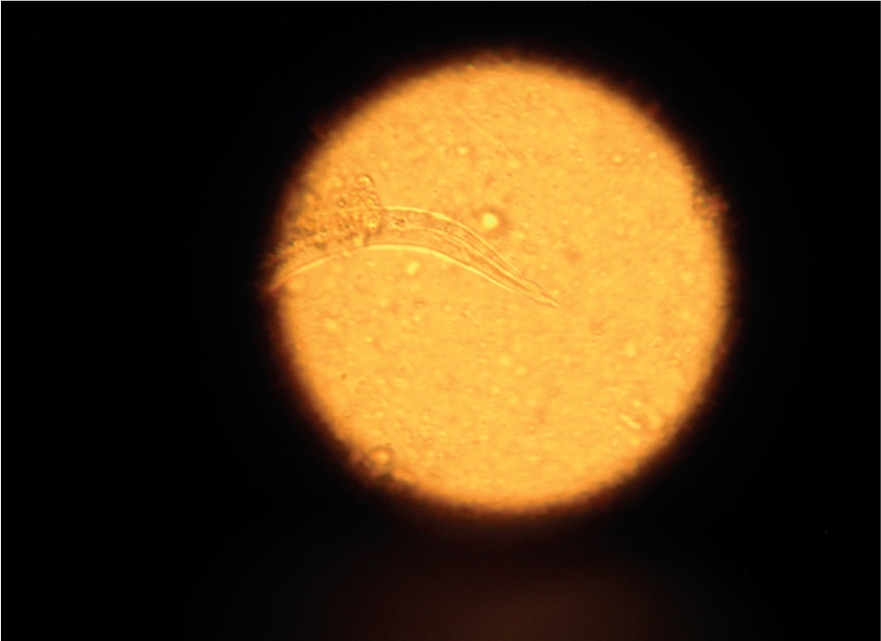

Direct smears only analyse very small volumes of faeces and as a result are considered too insensitive for the detection of helminth ova, which are passed in relatively few numbers. Lungworm larvae such as Crenosoma vulpis and A. vasorum (Figures 3 and 4) may be detected and is useful as an initial screen for these parasites, but the low sensitivity (54–61%) for the detection of lungworm by this method means it should not be relied on as a sole test if negative (Humm and Adamantos, 2010). A faecal sample approximately 1mm3 (the size of the head of a match) is mixed with a drop of water on a microscope slide and examined with a cover slip under the microscope.

Faecal flotation

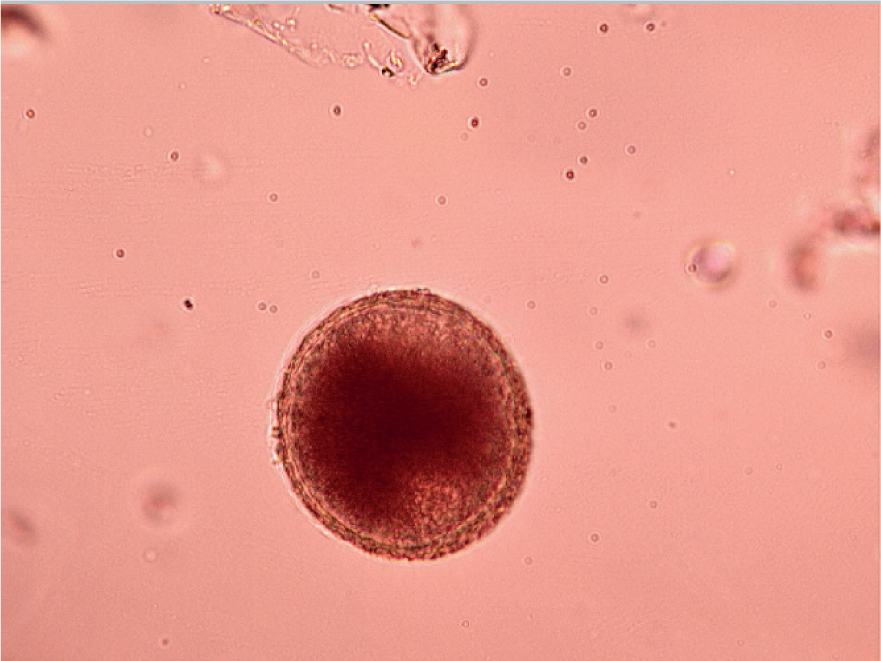

The faecal flotation technique allows much larger volumes of faeces to be examined by concentrating ova present in the faeces in small volumes of liquid while eliminating debris. This technique may still have diagnostic sensitivities as low as 60% for some ova such as Toxocara spp. (Figures 5 and 6) (Wolfe et al, 2001), but increases with pooled samples over 3 days.

Many different flotation methodologies are described in the literature, but an example is described below:

- The faecal sample is mixed with water (approximately 10 mls per gram of faeces) and stirred to form a suspension

- The suspension is then poured through a tea strainer to remove very large particles and decanted into centrifuge tubes. These can either be centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 15 minutes or allowed to stand for 20 minutes

- The water is then removed and the tubes half filled with flotation solution and mixed

- Each tube is filled with flotation solution until a meniscus is formed at the top of the tube

- A cover slip is then added, contacting the flotation solution

- The tubes are then centrifuged for 10 minutes (if a free swinging head centrifuge is available) or allowed to stand again for 30 minutes. If a fixed head centrifuge is being used then the cover slip is added to a meniscus after the second centrifugation

- Once these steps are complete the cover slips are lifted off the tubes and examined at x40 magnification under the microscope.

The flotation solution can either be sugar solution or zinc sulphate. Commercial preparations can be bought or prepared in house to a specific gravity or 1.2. Centrifugation of samples increases test sensitivity. If a veterinary practice does not possess a centrifuge then allowing the samples to settle over time is still useful as a routine screening test, but there will be some loss in sensitivity. The sensitivity and specificity of faecal flotation testing improves with operator experience at reading slides and identifying ova, therefore a dedicated RVN who has an interest in this area and has undergone training may be best suited to performing this test. Vetscan Imagyst® (Zoetis) is an artificial intelligence platform that performs scanning of faecal flotation slides for ova and identifies them, removing some of the operator error from reading faecal flotation slides.

Coproantigen testing

Antigens of some parasites can be detected in faeces, aiding in their diagnosis and routine screening. Antigen testing for intestinal roundworms, whipworms and hookworms are highly sensitive and specific and allow detection of parasites when ova shedding is not occurring, making it an excellent screening tool. Coproantigen testing is also possible for Echinococcus spp. tapeworms which is vitally important for screening programmes for these serious zoonoses. By the time infection is detected, zoonotic eggs would already be being shed, so testing by this method is not a replacement for routine treatment of dogs at risk of infection but useful surveillance alongside treatment. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can also be carried out on faeces to detect Echinococcus spp. and is highly sensitive and specific. Coproantigen test kits for intestinal roundworms are available from Idexx or can be performed by external laboratories.

The Baermann technique

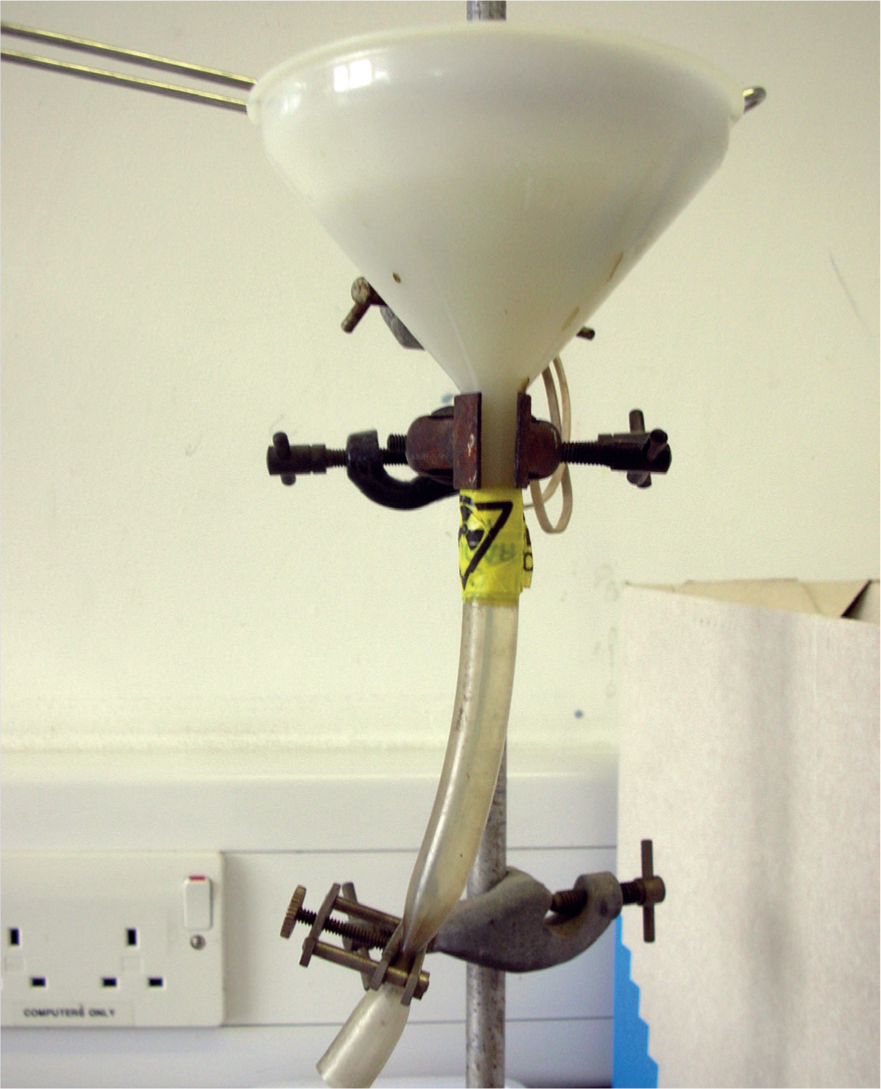

This technique is used for the detection of larvae in faeces. One of the advantages of the Baermann technique is that it requires inexpensive equipment, much of which can be reused for further tests (Figure 7):

- A rubber hose is attached to a funnel. This connection needs to be watertight over several hours so waterproof tape may be required depending on how tight the seal is.

- The two are suspended on a clamp stand with enough space underneath the tubing to allow collection of samples

- A clamp (or bull clip) is placed on the end of the tube. This should be able to be easily opened and closed to allow collection of the sample without spillage and possible loss of larvae

- Warm water is placed into a funnel until it is mostly filled. Enough space must be left to suspend the faecal sample in the water without overflow

- The faecal sample is wrapped in gauze and placed in the water in the funnel. It is easier to manipulate and prevent the sample from sinking and blocking the funnel if a stick or thin metal pole is placed through the gauze so it may be suspended in the water

- The warmth of the water activates the larvae in the sample, but they are unable to swim upwards against gravity. As a result, they drop through the gauze and down the funnel into the tubing.

- After 12–24 hours the clamp is released and 10–15 mls of water can be drawn off into a test tube. The sample can then be centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 1 minute and the resultant plug examined for larvae. If a centrifuge is not available the larvae can be allowed to settle to the bottom of the tube over an 8–12 hour period.

- Adding Lugol's iodine before examination kills the larvae, making identification easier.

If fresh, pooled samples are used, then sensitivity and specificity for lungworm detection by Baermann is high if the operator is experienced (Mesquita et al, 2017). It is a useful screening tool for lungworm and to demonstrate efficacy of lungworm control plans in cats and dogs. It is time consuming, however, and equipment can take up a relatively large proportion of laboratory space.

Blood antigen testing

Testing for parasite antigens in blood is useful for A. vasorum detection. While Baermann apparatus remains the gold standard for testing for A.vasorum infection, the patient-side blood test Angiodetect® (Idexx) has revolutionised A. vasorum testing. Only a small volume of blood in a serum or plasma tube is required which the RVN can obtain, and results are rapidly achieved (within 15 minutes) at relatively little cost. This has made the screening of large numbers of suspected cases of angiostrongylosis more achievable in first opinion practice. It is highly specific and has a sensitivity of approximately 85% (Schnyder et al, 2014). Testing of suspected clinical cases (dogs with an unexplained cough, coagulopathy or neurological signs) and routine testing at annual welfare checks will help to build up a picture of whether A. vasorum is present in a local area and whether preventative treatment is required. It also helps to demonstrate good compliance and efficacy for dogs already on a monthly preventative treatment programme.

Testing for fleas

The European Scientific Council for Companion Animal Parasites (ESCCAP) UK & Ireland promotes a risk-based approach to parasite prevention and some parasites such as ticks, tapeworm and lungworm lend themselves well to this approach. This, however, is not the case for fleas. In 2018, a UK-wide survey found that 28% of cats and 14% of dogs were infested with fleas (Abdullah et al, 2019). These high percentages have animal health implications, with flea allergic dermatitis a common cause of skin disease in cats and dogs, as well as fleas being a cause of human irritation and revulsion. Fleas also have the potential to transmit zoonotic vector-borne pathogens. No risk factors have been identified in the UK that make pets more or less likely to be exposed to fleas. The exception is a slight geographical gradient from North to South, but this is not significant enough to prevent unprotected pets from being exposed to fleas over time. Centrally heated houses also allow flea populations to be maintained in homes all year round. Year-round flea control is therefore required to maintain both animal and human health. If flea combing is relied on for flea detection before treatment this will allow flea infestations to establish before detection. Once present, flea infestations take months of treatment to eliminate. Checking for fleas routinely in practice is essential, however, to monitor for the presence of existing flea infestations and the efficacy of ongoing flea control.

Checking for fleas

When examining a patient for fleas a head-to-toe examination should be conducted with assessment of vital signs (TPR) and examination of the skin. This is of particular importance in those suspected of having a high burden that may be susceptible to anaemia, such as young puppies and kittens or those with a history of flea allergic dermatitis. If any abnormalities are found the patient should be referred to the veterinary surgeon. While a RVN cannot diagnose disease (this is an act of veterinary medicine as detailed in the Veterinary Surgeons Act 1966) they can present findings to the veterinary surgeon to assist in the process.

If a significant number of fleas are present they may be observed moving rapidly when the fur is parted or on areas with sparse hair growth such as the head and pinnae. It is easier, however, to assess for fleas using a flea comb. The coat should be brushed, and the debris collected placed onto damp cotton wool. Flea dirt will show red on contact with the damp cotton wool. An alternative method can be to place the sample onto a microscope slide and view under low magnification — blood will also be seen (Richmond and Wright, 2018).

Flea control

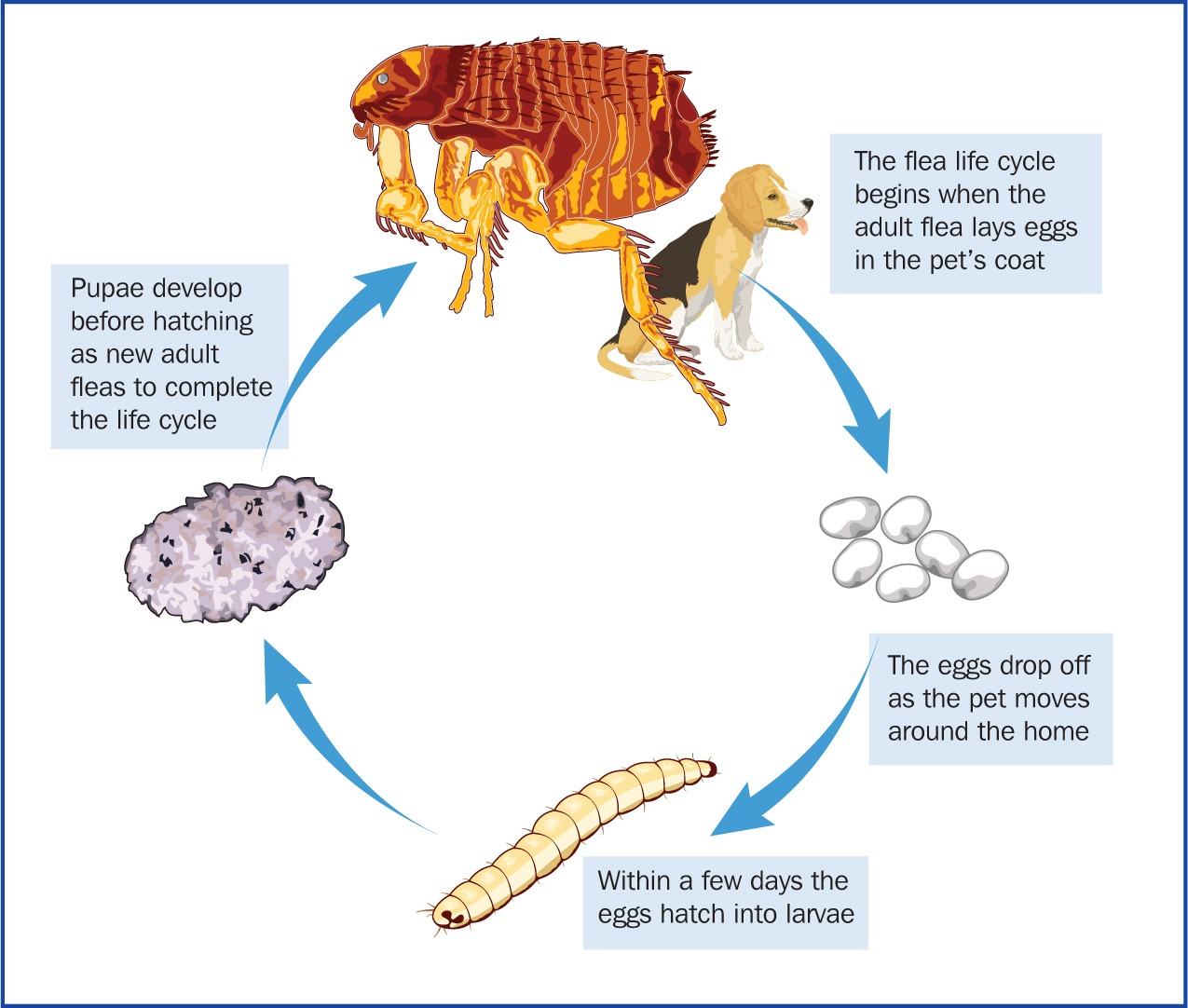

When discussing flea control with clients it is important they have an understanding of the lifecycle (Figure 8) of the flea so they can appreciate the need for treatment of both the animal and household; 95% of the problem is in the home, with only 5% of the issue, the adult fleas, being on the animal itself. The animal can pick up fleas from other animals, when out on a walk or they can be brought into the home on clothing. Adult fleas lay eggs within 24 hours and can lay up to 50 eggs per day. The eggs are approximately 0.5 mm in length, oval shaped and white so are difficult to see, they fall from the animal's coat into the environment and hatch in 1–6 days. In warm, humid conditions the larvae can pupate in 10–20 days with adult fleas emerging in around 3 weeks. Given the speed and multiplication of the lifecycle, just a few fleas can result in a large infestation, which can take months to clear. Pupae can also remain in the environment for 1–2 years if conditions are not favourable. Infestation can be re-established in response to heat and movement in properties that have been vacant, it is therefore not uncommon that clients may report issues with fleas following a house move, despite not previously having had issues. When considering product choice, the adulticide chosen must kill fleas within at least 24 hours and be applied frequently enough to prevent flea egg laying. Environmental control — use of a spray containing a larvicide/ovicide and insect growth regulator, regular vacuuming and washing of bedding at 60°C is also recommended (Richmond and Wright, 2018).

Checking for ticks

Preventative tick treatment is required for cats and dogs at increased risk of tick exposure, such as those visiting animal burrows, walking in rural areas, rough pasture or land used by deer or ruminants. There may also be a history of previous tick attachment. No tick preventative product, however, is 100% effective and it is important for pet owners to be vigilant and check for ticks on their pets every day, removing any ticks with a tick removal device or fine pointed tweezers. Checking for ticks is also an important part of routine health checks carried out be veterinary surgeons and RVNs. During parasite clinics, the VN can identify those cats and dogs at increased risk of tick exposure and educate clients on the correct methods of tick removal and the reasons for this. If tweezers are used the tick should be removed with a smooth upward pulling action. If a tick hook is used, then a simple ‘twist and pull’ action is employed. It is important that owners are instructed how to remove ticks without stressing them and without leaving the head and mouthparts in situ. Squashing or crushing ticks in situ with blunt tweezers or fingers will stress the tick leading to regurgitation and emptying of the salivary glands, potentially leading to increased disease transmission. Traditional techniques to loosen the tick, such as the application of petroleum jellies or burning, will also increase this likelihood and are contraindicated.

Identification and recording of ticks found on dogs and people is important to map their distribution, monitor potential introduction of exotic ticks to the UK and know which pathogens may have been passed on to dog or owner. Ticks may be identified using the tick University of Bristol tick identification site http://www.bristoluniversitytickid.uk. This is an area a RVN could become involved with in practice.

Public Health England are also happy to receive ticks for identification. Ticks should be placed in a container with a secure lid and sent in an envelope marked ‘biological sample’ and sent to:

- Tick surveillance scheme

- Public Health England

- Porton Down

- Wiltshire

- Salisbury

- SP4 0JG

Samples should ideally be unfed or only partially engorged as features on the scutum and festoons may be partially obscured by engorgement. Tick surveillance forms and further information can be obtained from The Gov.UK website under ‘tick surveillance’.

Blood antibody serology

Antibody serology is useful to demonstrate exposure to Borrelia spp., a tick-borne pathogen and the cause of Lyme disease. This can support a diagnosis of Lyme disease if relevant clinical signs such as fever, lymphadenopathy and joint disease are present. It is also useful to screen dogs in highly endemic areas as part of the annual wellness check to establish if exposure to the pathogen is occurring.

Conclusions

RVNs are instrumental in the creation of parasite control plans through educating clients on parasitic risk and benefits of routine diagnostic testing in dedicated parasite clinics or when assisting veterinary surgeons with consultations. While RVNs cannot diagnose disease, they can identify parasites and provide the veterinary surgeon with results to aid diagnosis and guide treatment plans. Sample collection and the performance of tests can therefore be delegated to the RVN. This is an area where RVNs can develop advanced laboratory skills and they can take ownership of these tests. This will result in increased job satisfaction for the RVN via improved animal and human health and the ability to fully utilise their skills and potential in this area.

KEY POINTS

- Cats and dogs are exposed to a wide range of parasites, some of which are ubiquitous, and exposure is therefore hard to avoid.

- Regular preventative treatment for Toxocara spp. and fleas is recommended, other parasite prevention is based on risk.

- Diagnostic testing is useful in surveillance and monitoring the effectiveness of parasite control plans.

- Sample collection and in house testing for worms (intestinal nematodes), fleas and ticks can be performed by the veterinary nurse to assist the veterinary surgeon with diagnosis of disease and formulation of treatment plans.

- The veterinary nurse plays a vital role in educating clients on the importance of parasite control to include treatment of the pet and household and the benefits of routine diagnostic testing.