A pneumothorax occurs as a result of an opening in the chest wall or damage to the pulmonary parenchyma which causes air to enter the pleural space and is commonly due to trauma (Fuentes and Swift, 1998). A chest drain, also known as a thoracostomy tube or thoracic drain, may be used to manage patients with a pneumothorax (Halfacree, 2011). Day (2014) states that chest drains are indicated in situations including: pyothorax management, following thoracic surgery, if negative pressure is not attained following thoracocentesis and if repeated thoracocentesis is essential for ongoing pneumothorax management. The most common complications seen in patients with a chest drain are: infection, patient interference and iatrogenic pneumothorax (Day, 2014).

Signalment

- Species: Canine

- Breed: Lurcher

- Age: 4 years

- Sex (neutered status): Male (neutered)

- Weight: 31.3 kg

Reason for admission

The patient presented after running into a stick which penetrated his thorax adjacent to the sternum.

Patient assessment

On initial assessment the stick was clearly visible entering the patient's thoracic cavity. The patient was tachycardic (150 beats per minute), dyspnoeic (36 breaths per minute) and hyperthermic (39.3°C). He had a normal capillary refill time (<2 seconds), pale pink mucous membranes and was noted to be hypoxaemic with the the percentage of oxygenated haemoglobin (SpO2) at 80%.

Veterinary investigations

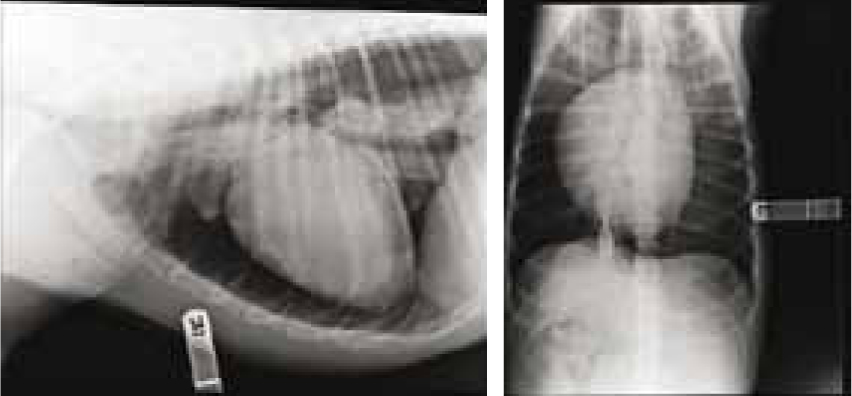

On admission a 20G intravenous catheter was placed into the patient's cephalic vein and a bolus of compound sodium lactate (Hartmann's solution, 30 ml/kg) was administered over 30 minutes to treat the patient's hypovolaemic shock. Flow-by oxygen supplementation (5 litres/min) was provided during the assessment and investigation stages. The patient was sedated (midazolam 0.2 mg/kg) to obtain radiographs to identify the location of the stick and assess the severity of the injuries. The radiographs revealed that the patient had a tension pneumothorax (Figure 1), which is caused by air entering the pleural cavity but not able to be expelled through the same entry point during expiration (Fuentes and Swift, 1998). It was necessary for the patient to have a general anaesthetic to allow removal of the stick from the patient's chest, enable intermittent positive-pressure ventilation to improve the patient's hypoxaemia and allow placement of a chest drain to manage the patient's pneumothorax. On recovery the patient had a temperature of 38.7°C, a heart rate of 80 beats per minute, pink mucous membranes and an SpO2 of 98%.

Discussion of nursing interventions and recommendations for future practice

Draining the chest

It was the registered veterinary nurse's (RVN's) responsibility to aseptically and efficiently remove the air from the patient's chest and to communicate findings, such as the volume and colour, by completing the patient's hospital sheet and informing the veterinary surgeon (VS) (Day, 2014). Intermittent thoracic drainage was used as there was no concern about air accumulating rapidly. If this had been the case then continuous suction could have been implemented, however this is not commonly indicated (Day, 2014). Day (2014) suggests the chest should be drained every 1–4 hours but this does depend on how quickly air is accumulating. The VS decided that it was necessary for the RVN to initially drain the chest every hour during the patient's recovery. Carne (2011) proposes that ensuring equipment and materials are to hand is essential for achieving successful drain management. Therefore the equipment and materials required to drain and manage the chest drain (Box 1) were placed in a box outside the patient's kennel and refilled when used to allow rapid emergency intervention if required (Day, 2014).

Box 1.Equipment and materials required for thoracic drainage and management

- Sterile gloves

- A bowl

- A three way tap

- Sterile syringes

- Sterile closed cap bungs

- Chlorhexidine solution (Hibiscrub, Mölnlycke Health Care Limited)

- Bandage materials

It is crucial to maintain asepsis when draining a chest drain to reduce the risk of hospital acquired infection (Aldridge and O'Dwyer, 2013). Asepsis can be achieved by implementing an effective hand hygiene protocol, wearing appropriate personal protective equipment and efficiently cleaning the drain site. Halfacree (2011) states that when handling a chest drain effective hand hygiene is essential to reduce the risk of infection. The RVN washed her hands by following the recognised World Health Organisation (WHO) guidelines and wore sterile gloves when handling the chest drain (Allegranzi and Pittet, 2009). The chest drain site was cleaned daily with chlorhexidine solution before applying a new thoracic bandage. The cleaning solutions commonly used for cleaning chest drain sites are chlorhexidine solution and povidone-iodine solution (Aldridge and O'Dwyer, 2013). Chlorhexidine solution was used because Bowers (2012) states it has a good residual activity compared with povidone-iodine solution.

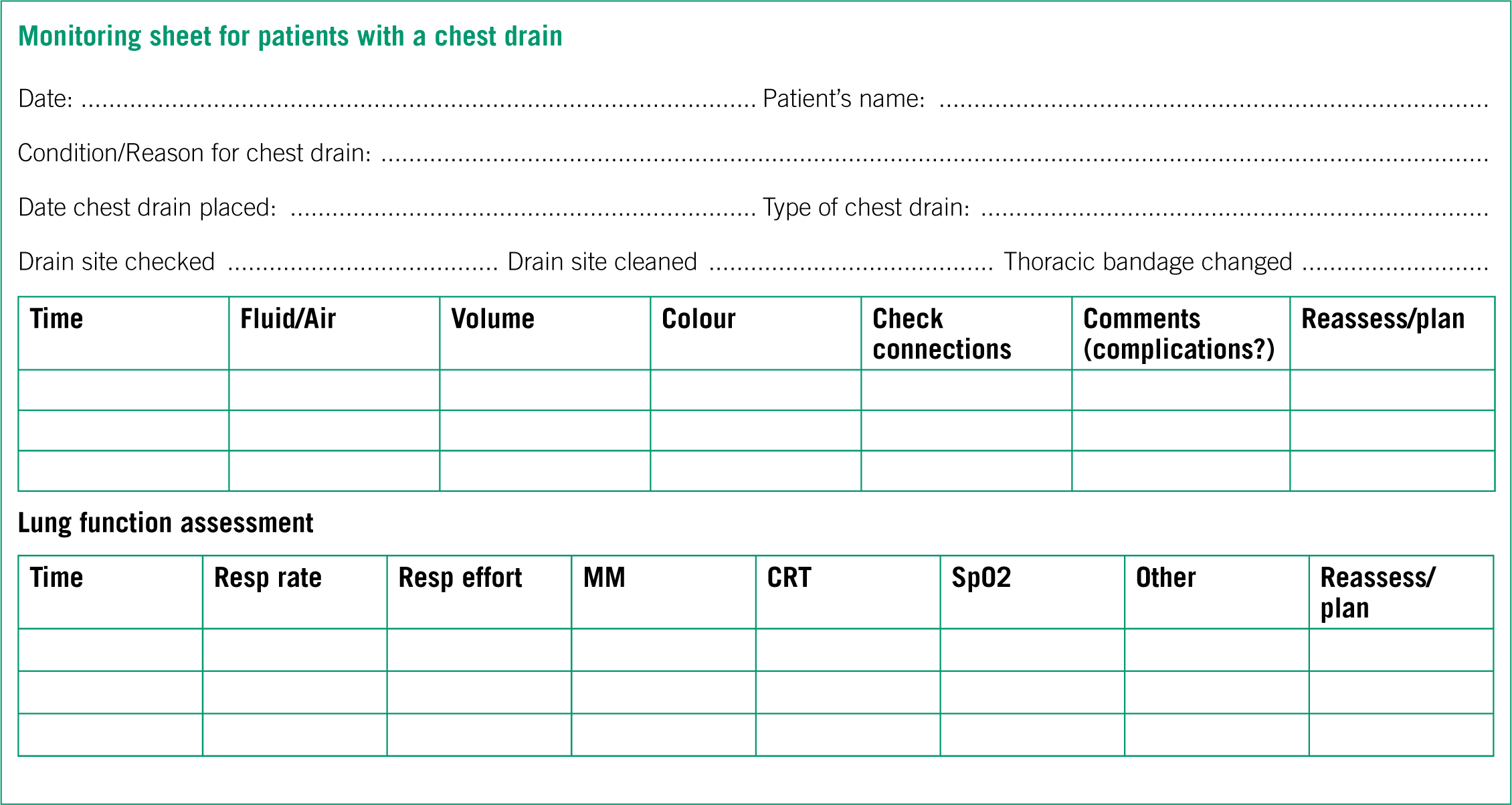

The RVN drained approximately 20 mls of air during the first 3 hours after placement. The chest drain was removed 12 hours after achieving negative pressure. Day (2014) proposes patients with a pneumothorax should have their chest drain removed once negative pressure has been attained for 12–24 hours. Furthermore, Halfacree (2011) states that patients should still be intensively monitored following chest drain removal as signs such as increased respiratory rate and effort could occur which would suggest a recurrence of air or fluid accumulating in the chest cavity. After draining the chest the RVN recorded all findings on the patient's hospital form and communicated the information to the VS. A future recommendation would be to have a specific monitoring sheet for patients with a chest drain. This would ensure there is enough space to record all observations including what was drained, how much was drained and if there were any complications (Figure 2). This recommendation would also improve the standard of nursing care by ensuring all members of staff are monitoring and recording the same series of observations.

Nursing the patient with a chest drain and preventing patient interference

The two most common complications seen in patients with a chest drain are patient interference and difficulties with the chest drain, such as disconnection of connectors and subcutaneous leaks around the tube (Day, 2014). The risks of these complications can be minimised by delivering a high standard of nursing care. Halfacree (2011) states that patients with chest drains require intensive monitoring to ensure that these complications are prevented which, in an ideal situation, would involve an RVN staying with the patient continuously. It was therefore essential to ensure the chest drain was protected to prevent any complications that may occur, such as infection, iatrogenic pneumothorax and patient interference.

There are many methods that can be used to prevent patient interference with a chest drain. Halfacree (2011) proposes the options for protecting a chest drain include: a thoracic bandage, a stockinette dressing over the chest and an Elizabethan collar. The use of an Elizabethan collar is encouraged and strongly recommended to prevent self-mutilation (Elliston et al, 2012). Another advantage of using this method is that patients do not require constant direct supervision, which is not always possible to achieve in a busy hospital ward (Halfacree, 2011). However, Griggs (2014) suggests that Elizabethan collars may cause stress and depression for patients. Common signs of stress and depression exhibited by patients in hospital can include: hypersalivation, vocalisation, lethargy and reluctance to eat and drink (Hargrave, 2012). An Elizabethan collar was placed on the patient during recovery to prevent patient interference and the patient was closely monitored for signs of stress and depression which were not reported.

As Halfacree (2011) has stated the other methods used to prevent patient interference in patients with a chest drain include a thoracic bandage and a stockinette dressing. A thoracic bandage, which covered the patient's chest drain, was applied while he was anaesthetised. A sterile dressing over the drain site was applied aseptically and the bandage was applied carefully to prevent it being too tight which could impair breathing (Halfacree, 2011). Lima et al (2011) suggest if the incorrect pressure is applied to a bandage problems can arise: it could cause the bandage to slip if applied too loosely or cause the patient discomfort if applied too tightly. However the correct pressure is not stated and is therefore open to interpretation. From previous experience the author suggests placing two fingers between the bandage and the patient to assess the tightness of a bandage. The thoracic bandage allowed staff to have easy access to the chest drain once the patient was awake. The bandage was changed daily and this allowed examination of the drain insertion site. Lima et al (2011) recommend daily bandage changes to enable monitoring of the healing process if a wound is present. However, Day (2014) proposes that the chest drain site should be examined twice daily to identify any signs of infection. The author favours thoracic bandages over stockinette dressings in patients with chest drains because stockinette dressings can easily tear and they do not provide as much support and protection as a thoracic bandage. Halfacree (2011) states that dressings for chest drains need to provide support and protection. It is evident that, as well as using an Elizabethan collar, another method of preventing patient interference should be used in patients with chest drains, as the patient could still cause damage by using their hind limbs and the surrounding environment.

Chest drains, if managed incorrectly, can compromise the patient's health and welfare. Day (2014) suggests this can lead to injury and even death of the patient, therefore patients require continuous and intensive monitoring. The patient's lung function was monitored by assessing his pulse rate, respiratory rate and effort, capillary refill time, mucous membrane colour and SpO2 (Day, 2014). Every hour, when the chest was drained, the RVN examined the area around the tube for leaks and ensured the connections were not loose, as this would have allowed air to enter the chest cavity and cause an iatrogenic pneumothorax (Halfacree, 2011). All observations and findings were recorded on the patient's hospital sheet and communicated to the VS. There were no complications with the patient's chest drain due to frequent monitoring and accurate communication.

Pain management

It is expected that a patient with a chest drain is experiencing a degree of pain, although Bloor (2012) suggests this is a commonly overlooked nursing intervention in thoracic drain patients. The degree of pain the patient is experiencing does depend on the underlying reason for the chest drain, for example patients that have undergone thoracic surgery will require more intensive pain management than patients with pleural space disease (Day, 2014). The majority of chest drains are made from either PVC or silicone, both materials allow the drain to be flexible and comfortable. The size of the chest drain can affect the degree of pain the patient experiences caused by the chest drain being in place. Day (2014) proposes an unnecessarily large drain can be associated with increased pain and discomfort and smaller tubes are usually adequate for removing air from the chest. The use of multi-modal analgesia is recommended in patients with a chest drain and the options available include: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), opioids and local anaesthetics (Day, 2014). Bloor (2012) suggests multi-modal analgesia should be implemented in injured and critically ill patients because by administering a range of drugs the pain pathway is interrupted at multiple locations, consequently providing an effective pain management protocol.

NSAIDs are medications that have anti-inflammatory properties and are used in patients with acute and chronic pain (Cracknell, 2011). Meloxicam (Metacam, Boehringer Ingelheim) (0.2 mg/kg subcutaneous injection), a commonly used NSAID, was administered to the patient during recovery. It was administered once the patient no longer displayed signs of shock or dehydration, as administering a NSAID to a dehydrated patient or a patient in shock could increase the chance of gastric ulceration and renal injury (Cracknell, 2011). Cracknell (2011) suggests NSAIDs should be used as part of a multi-modal analgesia plan to improve the patient's pain management, thus promoting the patient's health and welfare.

Buprenorphine (Buprecare, Animal Care) is a partial agonist opioid with a duration of up to 6 hours and is used in patients that are experiencing a mild to moderate intensity of pain (Auckburally and Yamaoka, 2014). Buprenorphine (0.02 mg/kg intramuscular injection) was administered to the patient on recovery as, although uncommon with buprenorphine, opioids may cause respiratory depression and the patient's respiratory system was already compromised on admission as he was hypoxic (Auckburally and Yamaoka, 2013). Auckburally and Yamaoka (2013) state that opioids have a depressant effect on the brain-stem respiratory centre which leads to a reduced response to hypercapnia and hypoxaemia. Buprenorphine was the opioid of choice due to its long duration and because it provides analgesia with minimal respiratory depression compared with full opioid agonists, for example methadone (Comfortan, Dechra) (Tompkins, 2013).

A future recommendation would be to administer bupivacaine hydrochloride, an intrapleural block with local anaesthetic, to reduce any pain or discomfort caused by the drain itself. This method of analgesia can be repeated every 6–8 hours and would also reduce the chance of patient interference (Day, 2014). This would be used alongside a NSAID and an opioid to achieve an effective multi-modal analgesia. In this particular case an intercostal nerve block was not used, but with future patients it could reduce any pain or discomfort caused by the incision (Day, 2014).

Pain scoring is increasingly being used in first opinion practice, thus increasing the standard of care that patients receive. This is achieved by standardising the observations monitored, increasing the frequency of monitoring and enabling the observations to be accurately recorded. A commonly used pain scoring assessment is the Short Form Glasgow Composite-Measure Pain Scale which is the only scale validated for acute pain in dogs (Crompton, 2010; Kronen et al, 2014). The patient was observed every hour, before the chest was drained, for visual signs of pain which included: vocalisation, trembling, altered behaviour and reluctance to mobilise. The physiological changes which occur were also taken into consideration and include: tachycardia, tachypnoea and salivation (Bloor, 2012). There was no formal pain scoring assessment implemented but any signs of pain the patient exhibited were recorded on the patient's hospital sheet. The patient did not exhibit any signs of pain due to frequent monitoring and the use of multi-modal analgesia.

Patient outcome

The patient remained bright and alert throughout his stay and he started eating shortly after the chest drain was placed. The chest drain was removed 12 hours after achieving negative pressure and his condition remained stable after the drain was removed. The patient was discharged 2 days after being admitted into the hospital and no complications occurred after discharge.

Conclusion

It is evident that nursing a patient with a chest drain involves many nursing interventions. The nursing interventions include: pain management, management of the chest drain, preventing patient interference and chest drain complications. It has been established that at least two methods of preventing patient interference should be used in patients with a chest drain to prevent self-mutilation. Also, by having the correct equipment at hand and maintaining asepsis successful drain management and a reduced risk of infection can be achieved. The standard of nursing care the patient received could have been improved by changing the thoracic bandage twice daily to allow more frequent monitoring of the chest drain site, because as Day (2014) suggests this would allow earlier recognition of any signs of infection. For future practice the use of intra-pleural local anaesthetics and intercostal nerve blocks and the implementation of a pain scoring assessment, such as the Short Form Glasgow Composite-Measure Pain Scale, could improve the standard of pain management the patient receives (Kronen et al, 2014).

Key Points

- Patients with a chest drain experience a degree of pain, although this is commonly overlooked it requires thorough attention from the registered veterinary nurse.

- It is recommended to use two methods to prevent patient interference and one method should be an Elizabethan collar.

- Successful drain management can be achieved by ensuring the correct equipment is at hand as well as maintaining a high standard of hygiene.

- A specific monitoring sheet for patients with a chest drain would increase the standard of care delivered by standardising the observations monitored and allowing accurate recording.

Conflict of interest: none

Radiographs included with owner's and practice's consent.