Behaviour problems remain a major underlying cause of abandonment and euthanasia of companion animals, particularly the dog and cat (PDSA, 2020). In addition, anxiety and fear-related behaviours of companion animals within the veterinary practice environment are a major basis for owners delaying the presentation of animals for essential veterinary treatment. For approximately 25 years there has been a growing wealth of evidence to support the use of synthetic analogues of canine and feline pheromones to assist in the treatment and prevention of the development of behaviour problems (Landsberg, 2015). Such products have, in combination with environmental management, behaviour modification and, where necessary, concurrent medication, supported the behavioural welfare of millions of companion animals, worldwide. Yet many veterinary staff remain unsure of the nature, mechanism of activity and advantages of the use of pheromonotherapy within patients' homes or within the practice environment.

What are pheromones?

Pheromones are biologically active semiochemicals (chemical signals from one organism to another capable of bringing about a change in the recipient organism); they are secreted from the body of one animal and result in a behavioural, hormonal or developmental change in another individual, of the same species (Wyatt, 2003). Pheromones normally consist of small chain fatty acids that form pro-pheromones that are secreted from sebaceous glands as products of metabolism. A binding protein (to enhance solubility within mucosal fluid) and a series of chemicals produced by the saprophytic organisms inhabiting the gland are added to this pro-pheromone, producing a pheromone ‘complex’ and giving the pheromone a ‘signature’ associated with its function and the individual producer (Hargrave, 2014).

How have pheromones been used commercially?

Pheromones have been successfully used to enhance commercial activity for centuries (Wyatt, 2003). Farmers have traditionally used pheromones to manipulate the behaviour of animals, for example in persuading ewes to accept orphan lambs. More recently, pheromones have been successfully used as a ‘greener’ alternative to control insect pests, to protect the honey bee, to reduce the distress of management techniques in fish farms and, over the last 25 years, in the management of stress experienced in commercial pig and rabbit units, animal laboratories and zoos. For approximately 20 years, pheromonotherapy has been available to the veterinary profession for the prevention and alleviation of stress experienced by the horse, rabbit, cat and dog.

How are pheromones detected?

To detect pheromones (Figure 1 (1)), mammals require a vomeronasal organ (VNO) (Wyatt 2003). The VNO (Figure 1 (3)) (approximately 3 cm long in the dog and 2 cm in the cat) is situated between the roof of the mouth and the main olfactory surface (Figure 1 (4)). The VNO opens at the anterior end, joining the naso-incisor canal (Figure 1 (2)) that leads to the nasal cavity. The VNO is not open during normal respiration (Christensen and White 2000), but on olfactory recognition of pheromones and visual recognition of pheromone-related signalling (e.g. oestrus related behaviour of females), animals engage in a Flehmen response, an upwards lip movement, sometimes assisted by tongue movements, that enables opening of the naso-incisor canal and the aspiration of air containing pheromones.

Once within the VNO, the specific pheromone complex mixes with the mucus of the VNO's epithelium where it comes into contact with species-specific binding sites on the VNO's epithelial surface, triggering the receptor site's sensory nerve (Figure 1 (5)); after this, there are two concurrent outcomes:

- The pheromone receptor site releases the pheromone complex, the pheromone being washed out and expelled with the mucus.

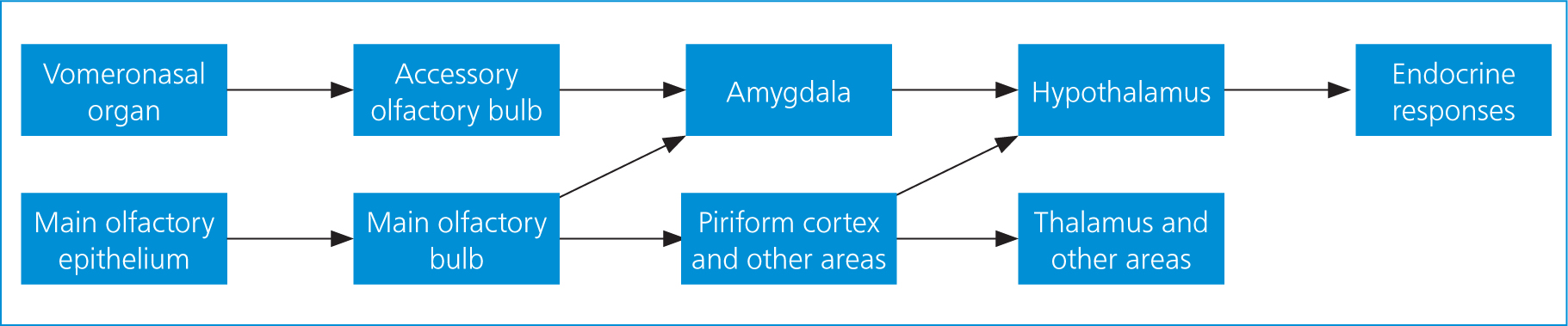

- The activated sensory neuron conveys stimulation to the accessory olfactory bulb within the brain (Figure 1 (6)), which, in turn, directly activates the amygdala (Figure 1 (7)), initiating a species-specific behavioural response (Figure 2).

As a consequence of this mechanism, there are two important results to the pheromone's activity:

- The amygdala activity, and associated behaviour, is activated without involving the conscious pathways of the brain — this is in direct opposition to the activity of the rest of the olfactory system that creates behavioural responses following activation of the piriform cortex and other conscious centres of the brain

- The pheromone does not enter the body. It creates a natural, species-specific response at the VNO's epithelium and then leaves the body, diluted in nasal mucus.

Resulting from the pheromone's unconscious activation of species-specific behaviour, is the possibility that animals can be assisted in adopting coping style behaviours, despite experiencing exposure to environmental stimuli that might otherwise result in distress (Figure 3).

What is pheromonotherapy?

Pheromonotherapy is the use of synthetic analogues of pheromones, that would normally be derived from natural bodily secretions, to modify the behaviour of an animal (Mills et al, 2013). The commercially available pheromono-therapy products are intended to alter an animal's perception of the environment through the unconscious stimulation of brain circuits associated with natural pheromones (Landsberg, 2015). As pheromonotherapy uses synthetic analogues of pheromones normally associated with an enhanced concept of recognition and familiarity, the use of pheromonotherapy assists the animal in coping, reducing the likelihood of the animal experiencing the emotions of anxiety or fear and hence reducing distress and its associated behaviours. Pheromonotherapy works through altering an animal's perception of its environment and as this response is unconscious, it removes the need for the use of methods of behavioural suppression, that might otherwise have been used by a family in its attempts to bring about behavioural change in their pet.

The main advantages of pheromonotherapy are:

- As the synthetic pheromones are effectively ‘messengers’ immediately released following their response at the VNO's olfactory surface, they do not penetrate the animal

- Although it is impossible to say that a treatment is without risk, because of its mode of action (and wealth of research studies — CEVA Comprehensive References, 2014) there should be no toxic or side effects associated with pheromonotherapy. However, there have been a small number of reports that owners have shown specific chemical sensitivities on contact with carrier mediums, e.g. with diffusers (please refer to the manufacturer's guidance sheets)

- The lack of systemic activity means that pheromone therapies are highly compatible with concurrent medication — including psychotropic medication

- In addition, pheromonotherapy is safe to use with very young, old or ill animals

- If a pet's behaviour problem is associated with the environment, then other household pets are also likely to be similarly affected, to some extent. Pheromonotherapy can benefit other household pets, of the same species, not yet showing obvious signs of distress. If another species of pet is present within a home, the use of one species-specific product will not interfere with a product designed to aid another species

- Possibly most important to your clients, pheromonotherapy is easy to use and hence, once applied, owner compliance becomes less of a barrier to recovery.

However, there are inevitable limitations to the products efficacy:

- Expectations regarding effectiveness in preventative strategies have to be proportional to the nature, and level, of exposure to a potentially distress-inducing stimulus

- Therapy should never be specifically used to enable the continuance of poor husbandry techniques

- In the early stages of development of a problem pheromonotherapy has, in some cases (CEVA Comprehensive References, 2014) been shown to aid a spontaneous recovery. However, pheromonotherapy is primarily intended to be used as an adjunct to an appropriate behaviour modification plan designed by a clinical animal behaviourist (see Box 1 for registers of practitioners). Some cases will be sufficiently severe to require other pharmaceutical support in combination with pheromonotherapy

- The correct pheromonotherapy product must be selected, meaning that staff education is paramount to success

- Care must be taken to follow manufacturer's guidelines regarding placement of devices to ensure that pets attempting to gain proximity to a device do not damage themselves or the client's home (e.g. if a device is placed behind a piece of furniture, an animal may scratch at the item to enable access to the device)

- The correct amount of product must be present in the environment — it is important that manufacturer's guidelines are followed to ensure that there is a sufficient concentration of product reaching the VNO for the organ to recognise the pheromone message and respond appropriately.

From the above, it is clear that there are considerable advantages to the preventative and therapeutic use of pheromonotherapy to both pet and owner (Landsberg, 2006). However, owner expectations must be carefully managed by staff promoting pheromone products (Mills, 2013), to prevent disappointment in the product and the potential for client loss of faith in the efficacy of advice provided by staff. In addition, poor sales advice may result in clients failing to follow-up disappointing results with further efforts to support the welfare of their pet.

Is pheromonotherapy similar to aromatherapy?

Aromotherapy relies on odours, especially essential oils, being detected by the main olfactory epithelium (Mills 2013). As shown in Figure 2, the behavioural results of odour chemicals, stimulating the main olfactory epithelium, rely largely on stimulating the conscious circuits of the brain and hence rely heavily on learned associations between the odour and a situation. In comparison, pheromonotherapy relies on the synthetic analogues of natural pheromones and their unconscious and predictable responses at the amygdala. As pheromonotherapy involves the receptor sites associated with an acceptance of familiarity and increased safety, resultant behavioural responses are specific and more predictable than those associated with aromotherapy.

Will clients see equivalent behaviour and welfare improvements from supplements or nutraceutical products?

There are a wide array of supplements, nutraceuticals and diets marketed and promoted for the reduction and eradication of stress-related behaviours in companion animals. The fact that these products are ‘natural’ can be very appealing to clients, who often fail to realise that there is a lack of quality, placebo-based trials of these products; nor are owners aware that such products may not have been quality controlled to the same level as pharmaceutical products. In addition, the potential side effects and toxicity of these products when combined with other similar products or prescribed medication, will be unknown (Baker et al, 2020).

When advising clients, veterinary staff have a responsibility to encourage clients to invest in products that have a scientific basis for their use and a proven effectiveness. Pheromonotherapy has over 25 years of research-based evidence (see CEVA Comprehensive References, 2014) to support its efficacy when used alongside appropriate environmental and behavioural management. In addition, pheromonotherapy does not require daily dosing of, or application to, an animal and is species-specific in its activity (compared with e.g. herbal diffusers being used within a home and potentially affecting both humans and other family pets).

How does pheromonotherapy help companion animals to cope in a domestic environment?

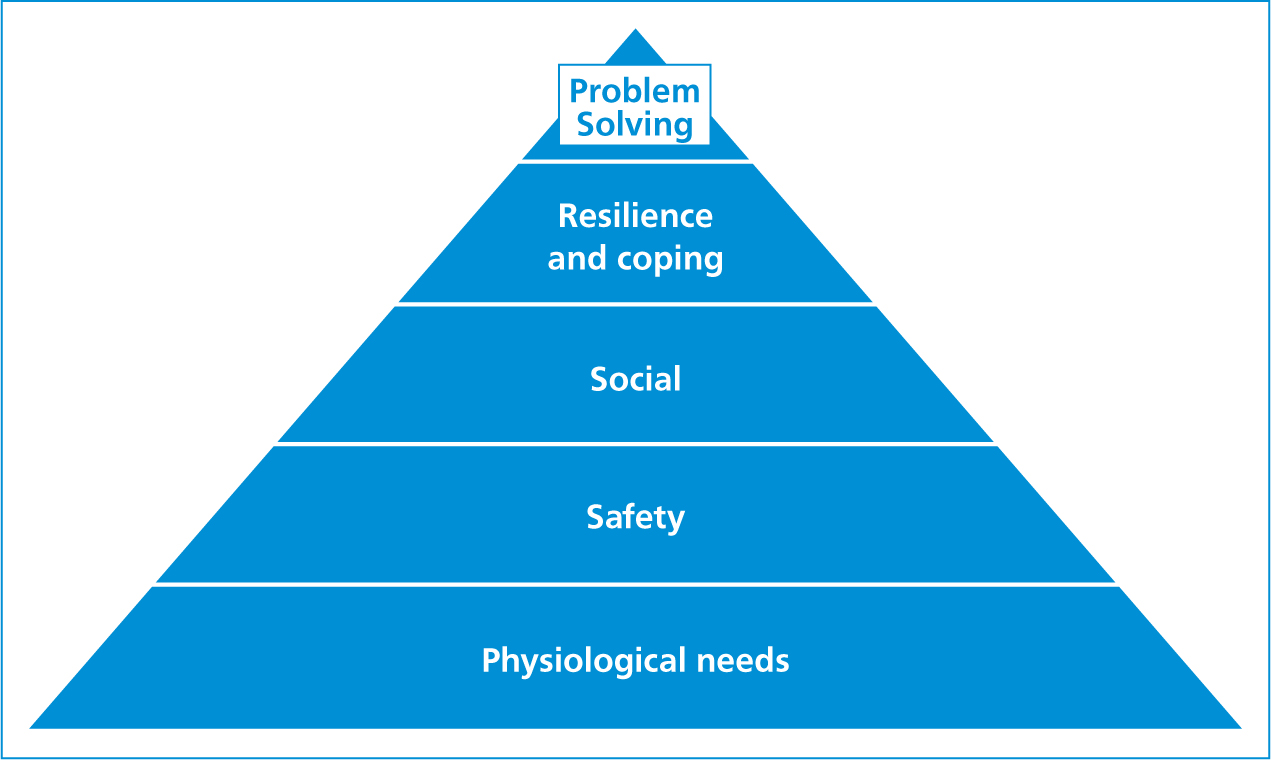

A concept of safety is important to any animal (Figure 4). Most basic to an animal's capacity to function is that its physiological needs are met (Maslow, 1943; Mills, 2013). After this, safe access to resources, without a need for conflict, is essential to psychological and physical wellbeing. However, if an animal does not have a sense of safety within its environment — if it cannot gain safe access to its basic resource requirements or if social relationships within the home are unpredictable and inconsistent — then the animal is forced to divert an excess of energy into resolving these safety-related problems (Mills, 2013). This leaves little opportunity for the animal to build more extended social relationships or to develop a greater level of resilience within its wider environment. Pheromonotherapy, in conjunction with environmental strategies, assists in the development of a concept of familiarity and safety within an environment. However, pheromontherapy is intended to act as an adjunct to environmental and behavioural management changes that enable families to meet the welfare needs of their companion animal — for sources of guidance regarding such changes, please contact a Clinical Animal Behaviourist (Box 1).

Box 1.Sources of behavioural support

- The ABTC register of Trainers and Behaviourists can be found at: www.abtcouncil.org.uk/index/abtc-members-by-region.html

- ASAB Accredited Clinical Animal Behaviourists: www.asab.org/ccab-register

- FABC Fellowship of Animal Behaviour Clinicians: www.fabclinicians.org/find-a-behaviourist

What types of pheromonotherapy are currently commercially available in UK?

In the UK, pheromonotherapy products are available to enhance an increased sense of coping within proximity to stressors for cats, dogs and horses.

- Feline facial pheromones (commercially available as Feliway Classic, Ceva Animal Health) – these products (diffuser and spray) are synthetic analogues of the F3 feline facial fraction pheromone, deposited by cats to enhance a concept of emotional stability within their environment. The natural pheromone would be rubbed at boundaries and passageways to mark familiarity with the item or area and to enhance the cat's spatial mapping of the area. Its absence in an environment leads to an increase in anxiety, but when present the enhanced sense of security has been shown to decrease anxiety-related behaviour, urine marking, scratching and social stress (Griffiths et al, 2000; Mills, 2013). As feline stress is linked to numerous feline medical conditions, Feliway can be an important addition to both preventative and treatment regimens (Landsberg 2015). The feline facial pheromone also has a role to play in enhancing coping in cats during veterinary visits, creating a greater sense of ‘control’ in an otherwise alien environment that lacks the cats own ‘security’ signals.

- Appeasing pheromones — it was long assumed that the mammary complex produced a chemical enhancing attachment between mother and new-born (Wyatt, 2003). In the late 1990s, mammary pheromones were isolated from a range of mammals (e.g. sows, cows, sheep and rabbits) and because of the appeasing affect that these pheromones had on both offspring and adults, the range of pheromones were called appeasines — appeasing pheromones. The pheromones help to orientate the young as they move around the environment, assisting them in perceiving the area as safe.

- Dog appeasing pheromone (commercially available as Adaptil, Ceva Animal Health) – the dog appeasing pheromone is produced shortly after giving birth, from the sebaceous glands between the mammary chains of the lactating female. The synthetic analogue of this pheromone (available as a diffuser, spray or collar) is recommended for the prevention, and management, of stress-related behaviours in the dog (including separation problems and noise sensitivities). As a result of its natural purpose, there is significant potential for the use of this product in the prevention of behaviour problems in the puppy and young dog, for example within the dog breeding industry, enhancing increasing environmental confidence and reducing puppy distress during separation from littermates and dam. In addition, the product can be useful in reducing puppy distress while travelling to a new home and becoming familiar with their new environment, both inside and outside the home (Danenberg and Landsberg, 2008; DePorter et al, 2013). There is also considerable potential for the use of this product to reduce the level of distress experienced by dogs during veterinary visits (Mills et al, 2006).

- Cat appeasing pheromone (commercially available as Feliway Friends, Ceva Animal Health) — produced shortly after the birth of her kittens from the cat's mammary region, this pheromone is intended to maintain a sense of safety and social harmony within the feline group while the mother is nursing her kittens. As cats lack the capacity to repair relationships following conflict or aggression, considerable social friction can develop within a multi-cat environment. The use of the synthetic analogue of cat appeasing pheromone, along with appropriate environmental management, can assist cats in coping with coexisting alongside other cats (CEVA Comprehensive References, 2014). Cat appeasing pheromone has a role to play in supporting cats when a new cat joins an existing group, as well as in reducing aggression-related behaviours between cats (DePorter et al, 2018) —including the stalking and chasing behaviours that owners may misinterpret as ‘play’.

- Equine appeasing pheromone (commercially available as Confidence EQ, Bimeda) — initially launched around 2005, this product, a synthetic analogue of the mare's appeasing pheromone, was withdrawn because of problems with application. This issue has now been resolved by presenting the synthetic equine appeasing pheromone within a gel that adheres to the horse's muzzle area, just below the nostrils. The product has been shown to reduce distress-related behaviours in horses being transported, clipped and shod (Falewee et al, 2006).

- Feline interdigital semiochemical (commercially available as Feliscratch, Ceva Animal Health) — claw maintenance through scratching of surfaces is a natural and necessary behaviour for the cat, but scratching is also used to demark territory both within and outside the home. By mimicking previous marking activity, the synthetic feline interdigital semiochemical can be used to assist owners in redirecting scratching behaviour from inappropriate surfaces onto scratch items intended for that purpose (Cozzi et al, 2013).

Recent innervations in pheromone therapy

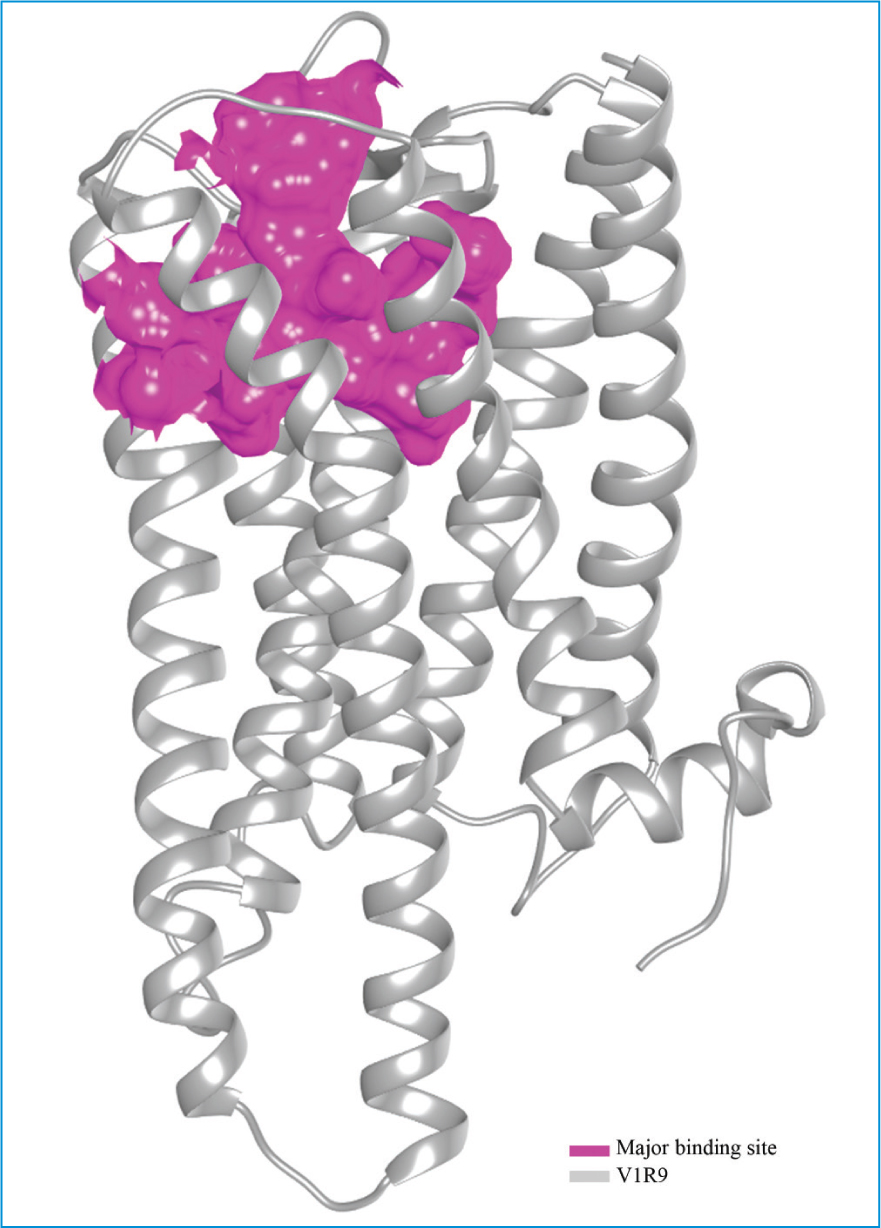

Until recently, the research and production of pheromono-therapy products have followed a similar pattern; decode the message of the pheromone, identify its composition, create a synthetic analogue that mimics the natural secretion of the animal and confirm its efficacy (Pageat, 2020). Further studies have established how natural pheromones can be modified by nature to improve their volatility and message strength and these enabled improvements to be made to the synthetic product. However, more recently, it has become possible to identify both the carrier protein for the feline pheromones within facial secretions, and to identify the 3D representation of the binding protein within the feline VMO for that carrier protein (Durairaj et al, 2019). This has opened up an entire new method of examining the gene bank for a species, identifying receptor sites and binding proteins and then, through computer imaging, creating the structures that bond to the binding proteins (Figure 5) and investigating their effects — all without the use of animals for experiments!

The future is bright for cats!

Today's domestic cat shows only a modest number of changes in the feline genome from its pre-domestication, solitary ancestor (Sparkes, 2020a). Domestic cats remain autonomous, with many experiencing difficulties in living alongside humans and other cats (Pageat, 2020; Sparkes, 2020a), often resulting in feline behaviours that owners find difficult to cope with, such as urine marking and scratching. For approximately 25 years, synthetic analogues of the facial (F3) pheromone has been available as Feliway Classic to assist with this problem and, more recently, Feliway Friends (Ceva Anmal Health) (the synthetic format of the cat appeasing pheromone) has assisted with social conflict problems between cats in multicat homes. However, the recent research has produced a targeted product, in the form of Feliway Optimum (Ceva Animal Health), capable of providing a message that the environment is stable and safe and that the proximity of other cats can trigger a positive emotional response (Pageat, 2020). Although studies of the efficacy of the new pheromonotherapy product are, as yet, limited (De Jaeger et al, 2021), Sparkes (2020b) reports that following 28 days of use of the novel product there was a highly significant reduction in cases of feline problem urination, fear, scratching and social conflict with co-habiting cats.

Conclusion

Pheromonotherapy, as an adjunct to appropriate behavioural and environmental modification, is a safe, easy to apply, evidence-based and effective method of both alleviating the behavioural signs of distress and preventing associated behaviour problems. As such, the use of pheromonotherapy should be an integral part of companion animal practice, supporting the welfare of patients that might otherwise be at risk of experiencing distress and potentially causing injury to themselves, other animals, members of the public and practice staff.

KEY POINTS

- Companion animals need a perception of safety within the home before they can be expected to relax sufficiently to investigate the physical and social environment outside the home without initiating arousal, stress and stress related behaviours.

- Arousal and stress initiate innate species-specific responses intended to create distance between the animal and the stressor — owners frequently find these responses to be inappropriate to owner needs.

- Behaviours associated with stress and arousal are likely to escalate because of a lack of owner understanding regarding the limitations of the animal's behavioural options once aroused.

- Synthetic analogues of natural pheromones can be used to improve the likelihood of a state of relaxation and consequently to increase the animals' behavioural options when faced with complex environments.

- Pheromonotherapy can boost the companion animal's concept of safety and improve the likelihood of it investigating, and responding appropriately to, the physical and social environment outside the home.

- Many cats find life in a domestic home to create welfare depleting challenges — recent advances in pheromonotherapy are likely to initiate a new era in the human owner's capacity to create a concept of stability and safety for their companion cats.