Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is the most commonly acquired cardiac disease in large and giant breed dogs. It is an important cause of cardiac morbidity and mortality, and Doberman Pinschers are one of the most commonly affected breeds. The two main reasons for death with DCM are refractory congestive heart failure (CHF) and sudden death caused by ventricular arrhythmias. Previously, treatment regimens started only when the patient presented with signs of heart failure. However, the pimobendan randomised occult DCM trial to evaluate clinical symptoms and time to heart failure (PROTECT) study (Summerfield et al, 2012) showed that the administration of pimobendan at the preclinical phase of DCM in Dobermans prolonged time to the onset of clinical signs, and extended survival.

Cardiomyopathy is a term applied to any cardiac disorder caused by myocardial dysfunction. In primary cardiomyopathies, the cause of the myocardial disease is unknown, and so the diagnosis of DCM is often one of exclusion (Dukes-McEwan, 2010). DCM is characterised by four-chamber dilatation and poor systolic function. Systolic dysfunction occurs because of an impairment of myocardial contractility, leading to activation of compensatory neurohormonal mechanisms (the adrenergic and renin–angiotensin–aldosterone systems), which result in fluid retention and progressive dilation of the ventricle. This dilation often also causes distortion of the mitral valve apparatus. This results in mitral regurgitation, which increases the potential for heart failure owing to increased pulmonary venous pressure and/or atrial arrhythmias. Some dogs remain in sinus rhythm, but tachyarrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation can also be seen. Ventricular arrhythmias can also be present, either as uniform or multiform ventricular premature complexes (VPCs), couplets, triplets, ventricular runs or ventricular tachycardia.

DCM is a slow, progressive disease, and is usually genetic. Breeds affected are generally large or giant breeds, but spaniels are also predisposed to DCM (Table 1). There is no sex predisposition, although males are more likely to present with CHF at a younger age (Dukes-McEwan, 2010). Generally age of onset is between 4 and 8 years (Dukes-McEwan, 2010); however, the age range can vary hugely, with some patients affected from as young as a few weeks old.

Table 1. Breeds with a high prevalence of DCM

| Giant breeds | Large breeds | Spaniel breeds | Other |

|---|---|---|---|

| Irish Wolfhound | Doberman | English Cocker Spaniel | Portuguese Water Dog |

| Deerhound | Boxer | English Springer Spaniel | |

| Great Dane | Weimaraner | American Cocker Spaniel | |

| Newfoundland | Dogue de Bordeaux | ||

| St Bernard | Golden Retriever | ||

| Leonberger | Labrador Retriever | ||

| Old English Sheepdog | |||

| German Shepherd Dog |

Patients can present with vague clinical signs, such as cough, exercise intolerance or weight loss, or with acute life-threatening CHF. Clinical signs of acute CHF include respiratory distress, cough (sometimes producing pink froth), and collapse. Sudden death may also occur. It has been shown that Dobermans are more likely to present with ventricular arrhythmias, which has been strongly linked to the higher sudden death rate in this breed (Calvert et al, 2000). Survival times for dogs diagnosed with CHF range from 2–4 months (Martin et al, 2010).

Stages of DCM

DCM has been described as having distinct stages (Table 2). The first stage contains dogs with no abnormal findings on echocardiography (echo) or electrocardiography (ECG); however, they are at risk of developing the disease at a later time. The next stage is the ‘occult’ or preclinical stage. During this stage, echocardiographic changes can be seen, such as left ventricular enlargement and/or VPCs can be identified on ECG. However no clinical signs are seen and the animal will generally appear outwardly healthy and normal to the owner. The final stage is CHF, also known as the ‘overt’ phase of DCM. As mentioned, even with optimal treatment, survival time once in CHF is generally very short (Martin et al, 2010).

Table 2. Phases of dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM)

| Stages of DCM | Clinical findings |

|---|---|

| 1. At-risk | Normal cardiac appearance on echocardiography and on electrocardiography (ECG), with no clinical signs |

| 2. Occult | Ventricular premature complexes are seen on ECG (a common finding with early stage DCM in Dobermans)And/or Echocardiographic changes start to appear, e.g. left ventricular dilatation |

| 3. Overt | Clinical signs of heart failure, +/- arrhythmias |

Screening

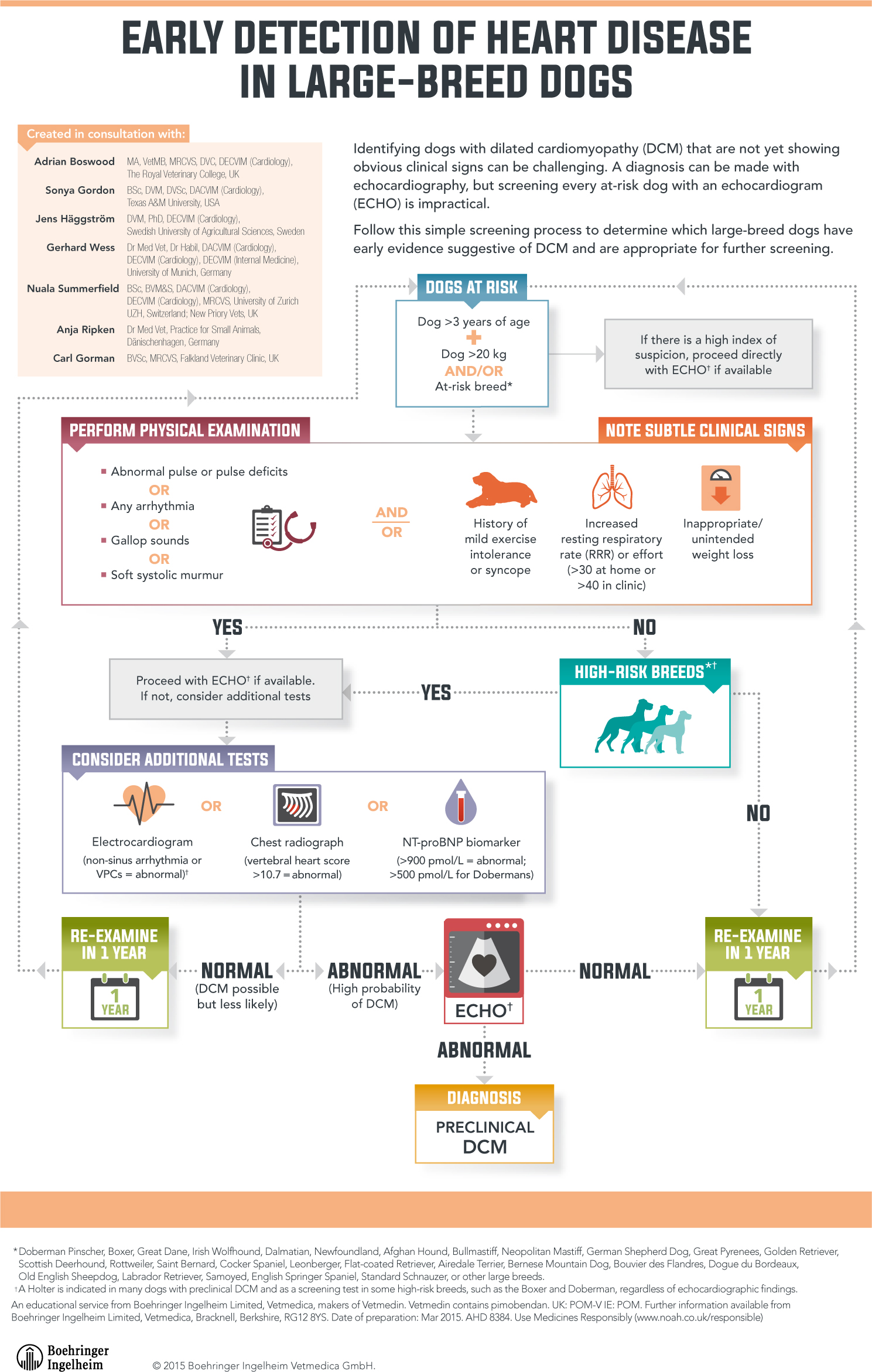

With such poor survival rates, it is imperative to recognise breeds at risk of developing DCM. Wess et al (2010) indicated that 25–50% of purebred Dobermans would develop DCM, and so for breeds with a known prevalence to DCM, screening is strongly recommended. Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica have produced a screening algorithm in association with leading European cardiologists (Figure 1). While the gold standard for diagnosing preclinical DCM is echocardiography, screening every dog in this way would present practical challenges, such as cost and access to specialists.

Therefore, this algorithm has been developed to determine which dogs are most appropriate for in-depth investigation and echocardiography. The steps include a full history and physical examination, and an NT-proBNP blood test leading to echocardiography and 24-hour ambulatory ECG (Holter) if appropriate (Figure 2).

As each patient and breed will vary, the benefit of echocardiography is that specific measurements can be taken for the individual of ventricular systolic and diastolic function, so a baseline can be established. Cardiologists have produced guidelines for ‘normal’ systolic function ranges, and Wess et al (2011) included specific ranges for Dobermans. There are also guidelines for the number of VPCs on a 24-hour ECG (Wess et al), 2011). Figure 2 shows a Doberman wearing a Holter monitor to measure heart rate and rhythm over a 24-hour period.

The NT-proBNP blood test measures natriuretic peptides, which are released in response to volume overload, hypertrophy and hypoxia of the cardiac muscle. Initially, NT-proBNP was shown to distinguish heart failure from respiratory failure, but further investigations led to linking NT-proBNP with diagnosing cardiac disease and severity of disease (Oyama et al, 2008). In 2012, Singletary et al (2012) showed that in conjunction with Holter monitoring, NT-proBNP was both sensitive and specific for detecting DCM in Dobermans. The benefit of this particular blood test is that it is a relatively cheap and easy way to identify dogs that would benefit from further screening. It is also suggested that NT-proBNP might help veterinary surgeons diagnose DCM when clinical signs are frequently absent (Oyama and Singletary, 2010). Furthermore, processing the blood sample is now easier, as the ProBNP assay is more stable (Box 1).

Box 1.How to process NT-proBNP blood samplesPlace blood in to EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) sample tube Centrifuge the sample *Separate plasma and place into a plain tubeTube must be clearly labelled with code BNPE CANINESamples should be sent by courier or guaranteed mail *** Note that samples ideally should be spun as soon as possible, but definitely within a maximum of a couple of hours** Idexx ProBNP assay is stable for 48 hours. If delays are expected in transportation (i.e. weekends), samples should be sent on iceAdapted from Idexx Cardiopet® proBNP test

Treatment

Before the PROTECT study was published in 2012 (Summerfield et al, 2012), treatment for DCM was initiated at the onset of clinical signs. This routinely included diuresis, pimobendan, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and spironolactone (frequently used, although not licensed for use in DCM). However, the PROTECT study (Summerfield et al, 2012) showed that administration of pimobendan at the preclinical, or occult, phase of DCM in Dobermans, prolonged the time of onset of clinical signs and increased survival time. Following the results of the PROTECT study (Summerfield et al, 2012), Vetmedin® chewable tablets are now also licensed for treatment of DCM in the preclinical stage in Doberman Pinschers following echocardiographic diagnosis of cardiac disease.

Conclusions

As discussed, DCM is ‘silent’ in the preclinical phase in that there are often no (or subtle) clinical signs. Veterinary nurses need to be aware of this important cardiac disease, because of its high mortality and morbidity rate. Recognising at-risk breeds and helping owners decide when and whether to screen, will not only help facilitate owner education but will help owners and vets with closer disease monitoring and making breeding decisions. Equally, it is recognised that sudden death may be seen as the first sign in affected dogs of certain breeds. For example, up to 30% of affected Dobermans present with sudden death before the clinical phase of the disease (Summerfield et al, 2012). Diagnosing preclinical DCM therefore also provides an opportunity, where appropriate, to slow disease progression, prior to the occurrence of such a serious outcome.

The Cardiac workshop was kindly sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica.