Gioso et al (2005) explained that the head of an animal is the most specialised part of the body as it houses the brain and sensory organs, all of which enable the animal to see, hear, smell, eat and taste, thus emphasising its importance. The development of skull, facial and orodental structures is complex, and begins in utero. Gracis (2013) outlined how each embryonic tissue contributes to the development of these structures, with the skull bones, alveolar bone, periodontal ligament (PDL) fibres, cementum, dentine and pulp all originating from the ectomesencyhme, a derivative of the mesoderm. The maxillae and mandibles arise from the first branchial arches.

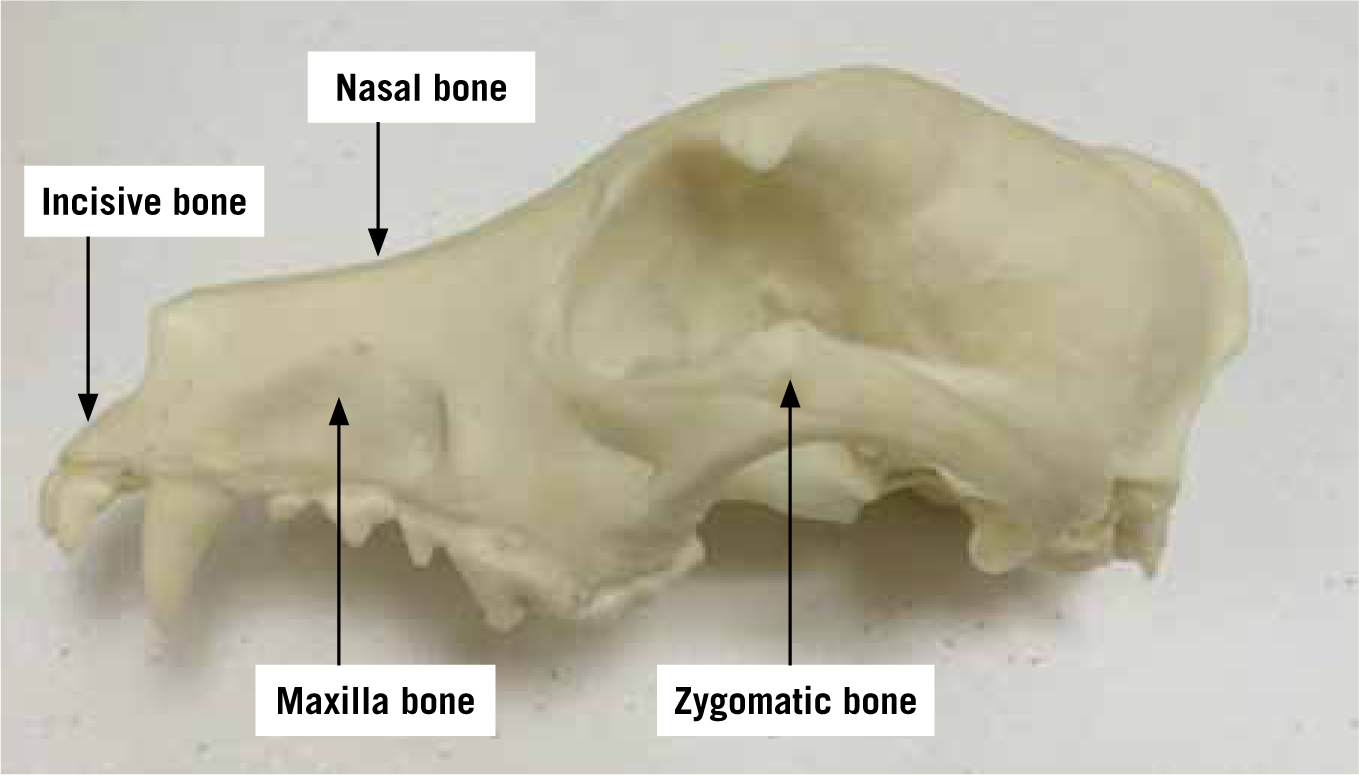

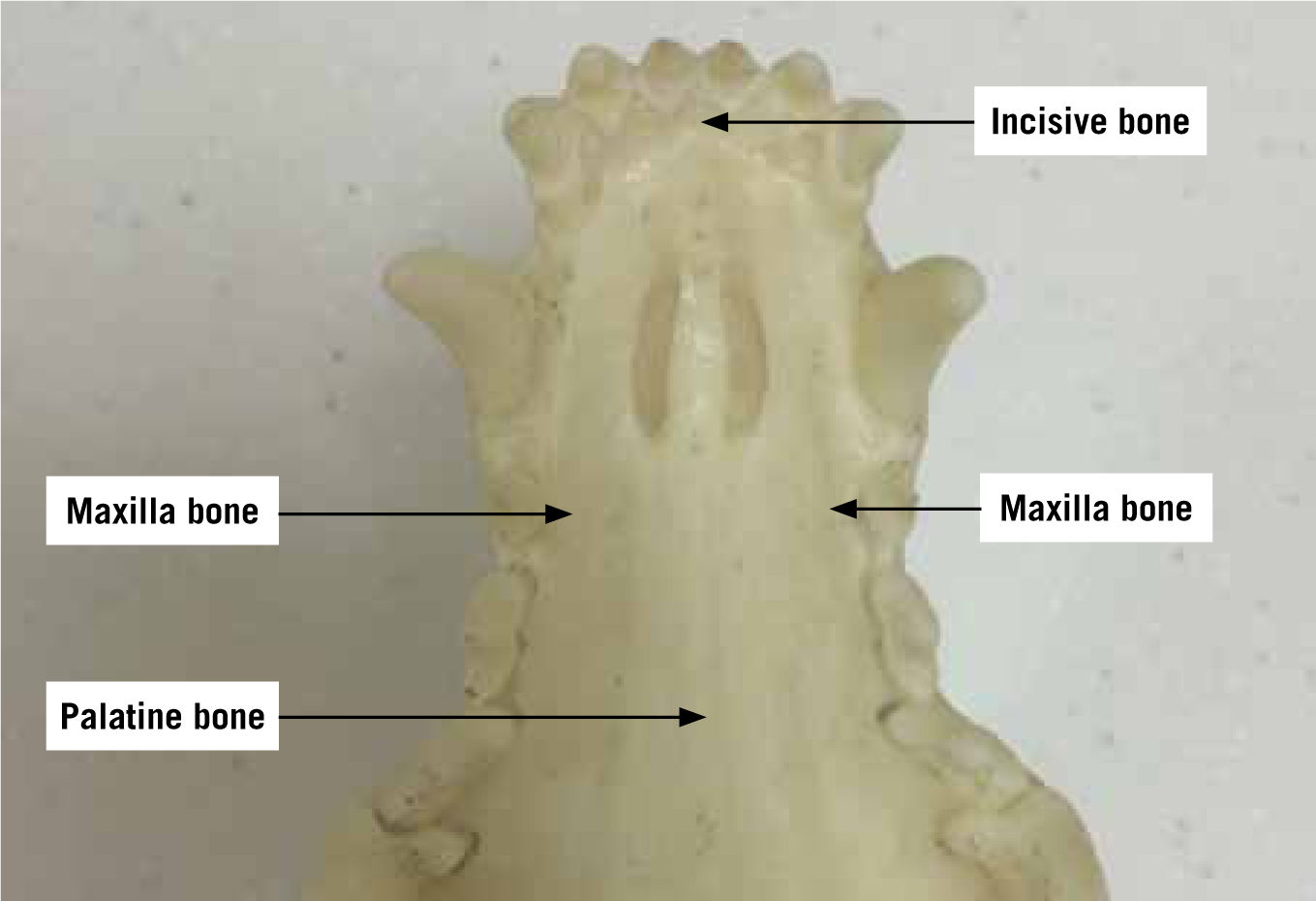

The jaws are the teeth-bearing bony structures which surround the oral cavity proper (Gracis, 2013), and the upper jaw is called the maxilla. The part of the maxilla that accommodates the majority of the upper teeth articulates with the incisive bone, nasal bone, vomer bone, temporal bone, lacrimal bone, zygomatic bones and the contralateral maxillary bones. The incisive bone houses the upper incisors, and the hard palate comprises the maxilla, palatine and incisive bones, forming the roof of the mouth; the bony separation between the oral and nasal cavities (Figures 1 and 2).

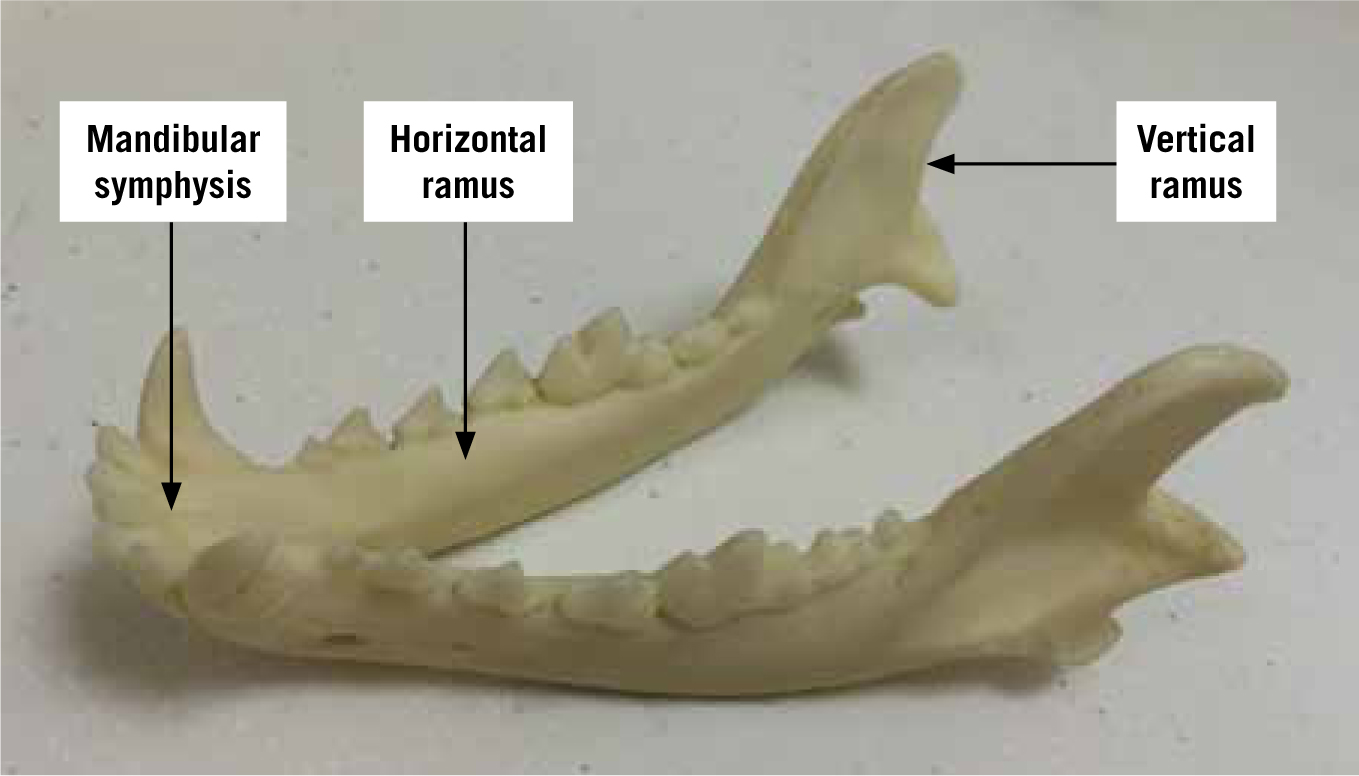

There are two mandible bones, or hemi-mandibles, which comprise the lower jaw, collectively known as the mandible. Each hemi-mandible features a toothless vertical ramus and a horizontal body which accommodates the teeth. These meet rostrally at the mandibular symphysis, which can create a bony fusion or remain a cartilaginous joint; this varies between animals (Gracis, 2013) (Figure 3).

Oral structure physiology

Gracis (2013) outlined the physiology of the oral structures, summarising the following as the main functions:

The process of chewing is complex and naturally relies on teeth being present in the oral cavity. The incisor teeth assist with prehension of food, before the tongue moves food from side to side to position it between opposing teeth. This facilitates mastication where the food is broken down and mixed with saliva prior to the process of deglutition. Bite force is modulated by the PDL and periodontal tissues, where a reflex exists between the periodontal mechanoreceptors and masticatory muscles; this reflex makes the animal reduce the bite force when a kibble has been broken, or when there is contact with opposing teeth for example, to reduce the likelihood of trauma to other teeth and supporting structures. This reflex also encourages an increased bite force when required, typically to keep the food between the dental arches and in the oral cavity, to stop it falling out of the mouth (Gracis, 2013). Where opposing teeth are missing following extraction, this reflex cannot operate properly and trauma or impaired mastication may ensue.

Tooth extraction

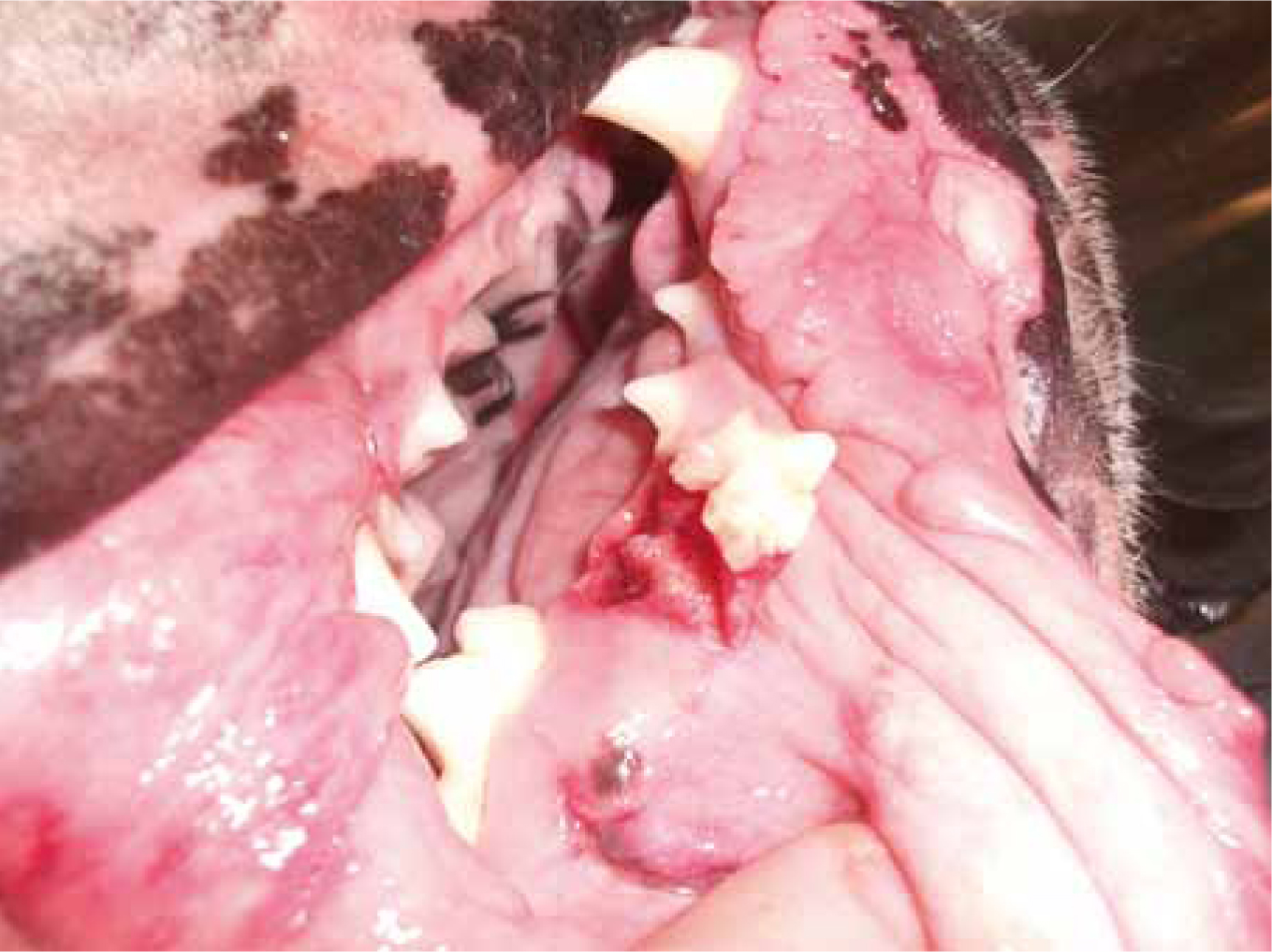

Reiter (2013) stated that extraction is the most frequently performed procedure in small animal veterinary practice, and reminded the reader that extraction is final; once the tooth has been removed it cannot be replaced (Figure 4). He stressed the need to use high quality, appropriate and well-maintained equipment to perform extractions, and the veterinary surgeon must use proper techniques to ensure the procedure is stress free, controlled and efficient in order to reduce trauma and therefore increase the rate of recovery and healing.

Reiter (2013) suggested the most common indications for the extraction of teeth in dogs are periodontal disease and fractures, whereas in cats it is due to feline odontoclastic resorptive lesions (FORL) or gingivostomatitis (GS), and Verhaert (2014) later concurred with this when discussing cats in particular, stating that apart from periodontal treatment, tooth extraction was the most common procedure performed (Table 1). Wherever an animal has established pathology, or where financial constraints mean advanced procedures to salvage the teeth are not viable options, Reiter (2013) advised that extraction is warranted; he advised extraction should definitely be encouraged as opposed to leaving pathology untreated. This sentiment was echoed by Gengler (2013)

| Key indications for tooth extraction | |

|---|---|

| Periodontal disease (dogs) (Figure 5) | Feline odontoclastic resorptive lesions (FORL) (cats) (Figure 6) |

| Tooth fracture (dogs) | Gingivostomatitis (cats) |

| Endodontic/periapical disease | |

| Combined periodontal/endodontic involvement where the tooth cannot be stabilised in its socket | |

| Advanced caries | |

| Persistent deciduous teeth (Figure 7) | |

| Traumatic malocclusions | |

| Supernumerary teeth | |

| Non-functional/malformed teeth | |

| Unerupted dentition | |

| Fractured or retained roots | |

| Crown/root fracture with pulp exposure (Figure 8) | |

| Osteomyelitis/osteonecrosis | |

| Neoplasia | |

| Diseased teeth in a jaw fracture line | |

| Traumatically displaced teeth (Figure 9) | |

| Client preference | |

Jennings et al (2015) performed a study to evaluate the long-term response of cats with stomatitis to tooth extraction, and concluded that the extraction of teeth from inflamed areas provided a significant improvement or complete resolution of the stomatitis in more than two thirds of their sample.

The following list outlines the key contraindications to tooth extraction:

Extraction: considerations and techniques

There are some considerations that all veterinary professionals must address prior to performing dental extractions, and Crossley (2006) suggested the main problem associated with extractions is that the operator is insufficiently prepared; they may have an inadequate diagnosis and therefore treatment plan. Gengler (2013) highlighted that a thorough understanding of extraction techniques is essential to minimise anaesthetic time, maximise patient comfort and be minimally invasive throughout.

With regards to the clients, the veterinary surgeon must offer alternatives to extraction where appropriate; it should be explained to them that extraction is final, and the complications associated with extractions should be outlined. This ensures the client can consider all options and make an informed decision regarding their pet's treatment (Reiter, 2013).

With respect to the patient, Reiter (2103) believed the veterinary surgeon must: ensure the animal is healthy enough for general anaesthesia; ensure the mouth is clean prior to extraction by performing a scale and polish, and then using a chlorhexidine 0.1–0.2% solution to disinfect the operating site (Crossley, 2006); administer antibiotics if the patient is debilitated, immunocompromised, has organ disease, has endocrinopathies, has cardiovascular disease, or has a severe local or systemic infection; take radiographs before extraction to evaluate the tooth root and identify any potential problems; and perform appropriate nerve blocks.

The veterinary nurse or technician plays a large role in the successful management of any dental procedure, which includes extractions; Sylvester (2005) believed a highly skilled and proficient technician is a highly sought after dental adjunct, as they enhance and maximise the efficiency of the veterinary surgeon. They must ensure they support the veterinary surgeon appropriately by making sure all of the equipment is prepared and in good working order, and they must plan the perioperative nursing management of the patient carefully and thoughtfully. It must be remembered that extraction of teeth is not within the remit of a veterinary nurse or technician unless it can be performed digitally — i.e. those teeth which are very diseased and have lost most of their attachment to the alveolus.

The veterinary surgeon, as previously mentioned, must be appropriately trained in proper extraction techniques, must wear the correct personal protective equipment throughout the procedure to protect themselves, and they must think about the whole procedure in terms of ergonomics; location of equipment, technique, seating, lighting and so on are all important for health and safety reasons.

Teeth can be extracted via a number of techniques, and the veterinary surgeon must be knowledgeable regarding which technique is suitable in each individual case they treat following a thorough assessment of the problem. The following list outlines the main extraction techniques:

Reiter (2013) warned that root pulverisation, which is using the high speed hand piece and a bur to try and pulverise, or drill away all remnants of the roots is not advisable and is indeed dangerous. Adopting this technique will: cause iatrogenic trauma; result in an incomplete extraction; overheat the tissues leading to bone necrosis and delayed healing; cause potential injury to neurovascular bundles; potentially cause repulsion of root fragments into the infraorbital and mandibular canals; potentially results in transected salivary gland ducts; cause subcutaneous and submucosal emphysema; and potentially result in an air embolism. There are reports in literature regarding the introduction of air in this manner, which was associated with severe consequences. Davies and Campbell (1990) reported on three fatalities in humans where an air embolism, produced by the inadvertent injection of a mixture of air and water passing through the dental drill, had passed into the mandible and then the venous circulation. Magni et al (2008) later reported on some non-fatal cases associated with cerebral air embolisms following dental surgery, where they surmised the likely cause of the embolism was the injection of air by the high speed dental drill through the soft tissues adjacent to the roots of the lower molars into the circulation. A final example of the potential risks associated with the use of a high speed drill in this manner is supplied Hagr (2010), who produced a case report about a lady who developed a pneumothorax following dental treatment and the use of a high speed drill. It was thought her pneumothorax developed due to the pressurised air from the dental drill being forced through the disrupted intraoral tissue barriers, which communicate with sublingual and submandibular spaces, then the pharyngeal spaces and finally the deep neck spaces and thorax.

Extraction: advantages and complications

The main advantages associated with tooth extraction are the fact that, with appropriate training, all veterinary surgeons can become proficient at the procedure; this means they will be able to remove teeth in a controlled and minimally traumatic manner, and there is no need to have lots of very expensive specialist/advanced equipment. Also, once a tooth is extracted in its entirety and there is no biologically active tissue remaining it is gone; it is final. Tooth extraction removes infection and relieves any associated pain simultaneously (Holmstrom, 2011), so once the alveolus and gingivae have healed there will be no more complications associated with the tooth and there is no need for follow-up radiographs for example, as there are with RCT.

There are, however, many complications associated with the extraction of teeth, which could be considered disadvantages associated with the procedure. These include:

The final two from this list warrant further discussion as they are common problems associated with tooth extraction that veterinary professionals may not anticipate as being too problematic. Reiter (2013) explained that trauma from opposing teeth following extraction is a particular problem in cats where the maxillary canines have been extracted. These canine teeth and their supporting tissues (the gingivae and bone) keep the upper lip out of the way of the lower canine tooth when the mouth is closed, however if these teeth are extracted the lower canines can cause trauma to the upper lip in the form of pinches, punctures and potentially lacerations, all of which are going to be painful.

Reiter (2013) further discussed the problems associated with the tongue of the animal hanging from the mouth, which is more pertinent to dogs than cats. The rostral mandibular teeth, canines in particular, create a ‘basket’ which serves to contain the tongue at rest, so removal of these teeth means the tongue frequently hangs out of the mouth instead. While this may not seem to be a significant problem in many dogs, it can result in the tip of the tongue becoming quite dry, but more importantly excessive salivation can occur and consequent lip dermatitis; this may require commisuroplasty surgery to help solve the problem or reduce its severity.

Alternatives to extraction

The main alternatives to tooth extraction involve various endodontic procedures, and Holmstrom (2011) discussed the indications for performing endodontic treatments to preserve teeth rather than extract them, which included:

The endodontic options include:

Holmstrom (2011) explained that endodontic therapies are considerably less invasive than the surgical extraction of large canine, premolar/molar teeth, so are easier and quicker to perform; these procedures should be done by specially trained veterinary surgeons to maximise the potential for a successful outcome. He also believes that standard RCT is less traumatic for the patient for the aforementioned reasons, and the outcome is more aesthetically pleasing for the owners when compared with extraction. The cost of RCT, depending on the individual veterinary surgeon's prices of course, is generally similar to a surgical extraction (Holmstrom, 2011), and because veterinary patients have a relatively short life-span in comparison to humans, an optimal RCT procedure is unlikely to fail within the patient's lifetime.

There are some disadvantages associated with endodontic treatments, including the requirement for referral to a specialist, which the owners may find challenging if the specialist is some distance away and potentially costly. Holmstrom (2011) however believes that a clinic should offer referral to clients if they are unable to provide the necessary treatment themselves, and this shows concern for the patient and client beyond the realms of standard veterinary care. Endodontic treatments should be periodically monitored radiographically (Gorrel, 2010) to ensure initial problems, such as periapical diseases, are resolving, and to identify whether the treatment is failing; taking radiographs will involve the patients having another general anaesthetic. Gorrel (2009) noted that when considering immature teeth and endodontic treatments, the veterinary surgeon must be mindful that multiple anaesthetics will be required, so in many cases where there are immature teeth with necrotic pulps, extraction is the best course of action.

There are a number of reasons why endodontic treatments might fail, including disease around the root apex or leaking materials if there is insufficient obturation and sealing, however, if they are performed meticulously by appropriately trained veterinary surgeons with strict radiographic control there is a high chance of a successful outcome (Gorrel, 2009; Gorrel, 2010). Gorrel (2009) also warned practitioners to avoid restoring these teeth to their original shape and size; the strong bit forces in dogs particularly will lead to failure of such a restoration. A study by Fulton et al (2012) documented the short and long-term outcomes of surgical endodontic treatments in dogs in a clinical setting, and they concluded this was an effective option for salvaging rather than extracting endodontically diseased but periodontally healthy teeth.

Nursing considerations

As previously mentioned, the veterinary nurse or technician is very much involved in the whole process of oral care management before and during surgery, however their role also extends into the postoperative period and beyond. It is vital the veterinary nurse or technician possesses the knowledge and experience to be able to plan appropriate post-operative care, provide the best aftercare to the patient, and advice to the owners on discharge. A nursing care plan can facilitate holistic nursing practice in this and all circumstances.

If a patient has had teeth extracted, various abilities/activities of daily living might be affected. It is the role of the veterinary nurse or technician to identify all actual and potential problems associated with these abilities, set short-term goals, and plan appropriate nursing interventions and reassessment times to meet the patient's dynamic needs, on an individual basis; all patients are different. An example of this assessment for a patient that has had extractions can be seen in Table 2.

| Ability / activity | Actual problem | Potential problem | Short-term goal | Nursing intervention/s |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eat | Extractions — sutured gums | Pain and reluctance to eat. Accumulation of food stuffs around suture line affecting healing | Ensure pain free. Eat a handful of chicken within 3–4 hours of the end of surgery | Ensure analgesics have been administered and plan when needs to be assessed again. Offer a hand full of warmed chicken (non-sticky) to patient — hand feed if necessary (owner said he eats when fussed) |

| Drink | Extractions — sutured gums | Pain and reluctance to drink. |

Ensure pain-free. Drink 200 ml water within 3–4 hours of surgery. Maintain hydration and perfusion WNL. Maintain intravenous fluid infusion and patency of IV catheter | Ensure analgesics have been administered and plan when needs to be assessed again. Measure and offer 200 ml water — do not leave in with patient as likes to tip bowl over. Use infusion pump to deliver hourly fluid requirement. Check IV catheter patency regularly (drip running/limb swelling) and remove and replace dressing twice a day. Measure blood pressure every hour for the first 4 hours post-op |

| Urinate | None | Pain and urine retention. |

Maintain normal urination | Adequate analgesia. Appropriate bedding in cage and clean up immediately any accidents. If recumbent monitor coat and skin for urine soiling. As soon as ambulatory, take outside to urinate and plan frequent opportunities for this |

| Defecate | None | Pain and faecal retention | Maintain normal defecation | Adequate analgesia. Appropriate bedding in cage and clean up immediately any accidents. If recumbent monitor coat for faeces soiling. As soon as ambulatory, take outside to defecate |

| Breathe | None | Pain may affect respiration/ventilation. Blood / saliva — may aspirate | Maintain normal respiratory rate and effort. Prevent aspiration | Adequate analgesia. Record resp rate every hour for first 4 hours post-op. Comment on respiratory effort at the same time. Regularly check oral cavity for blood and saliva — clear as necessary. Position patient appropriately during recovery to aid postural drainage of oral fluids |

| Maintain body temperature | Mild hypothermia post-op | Prolonged/persistent hypothermia. Effects on recovery, drug metabolism, wound healing | Achieve normothermia within 1–2 hours post surgery. Avoid hyperthermia | Initially place a heat pad in the kennel and cover patient with a blanket. Monitor temperature every 15–30 minutes initially. Alter interventions appropriately — use active warming methods if temperature not increasing sufficiently, and remove heat pad/blanket when the temperature is nearing normal |

| Groom/clean | Extractions—sutured gums | Pain and reluctance to groom. Incisors removed so grooming may be ineffectual—poor coat condition / mats | Maintain coat condition | Adequate analgesia. Groom the patient during the post-operative period (if they are amenable to this!). Do this when not performing other interventions — try to foster patient:carer bond |

| Mobilise | None | Pain may result in the patient being unwilling to do anything, including move. May be head shy if trying to put a lead on is oral discomfort present. If recumbent for a long period of time during recovery—atelectasis/hypostatic pneumonia/ischaemia over bony prominences | Encourage to mobilise within 1–2 hours of surgery. Prevent problems associated with recumbency from developing | Adequate analgesia. Appropriate soft bedding including orthopaedic mattress. Further padding of bony prominences if required. TLC — spend time with patient as this may encourage activity. Support mobilisation if required. If recumbent (prolonged recovery), ensure the patient is turned every 2–4 hours — encourage sternal recumbency where possible |

| Sleep/rest | None | Pain and stress can have dramatic effects on patient's ability to sleep and rest. Need to sleep and take adequate rest to promote optimal healing | Ensure patient is able to rest and sleep if they want to | Adequate analgesia. Appropriate kennel environment – bedding / comfort / temperature. Reduce environmental stimuli if this is preventing rest / sleep. House in a species-specific ward |

| Express normal behaviour | Extractions—sutured gums | If patient is unable to eat/drink/groom/go outside to eliminate/sleep/rest as they normally would, this ability could be affected | Ensure all other abilities and their problems are addressed. Maintain a near-normal routine as at home | Ensure all appropriate interventions from above are performed. Ensure information has been collected from the owner at admittance about the patient's ‘norms’, and use this information to guide nursing interventions |

If all of the interventions detailed in Table 2 are performed, short-term goals are met, and potential problems have not turned into actual problems then holistic nursing care while hospitalised would be deemed a success. The veterinary nurse or technician must be mindful however that all of these abilities will not be back to normal by the time the patient is discharged back into the owner's care. They still have extraction sites and sutured gums that will take time to heal, so a lot of the actual problems and potential problems will remain.

It is therefore advisable for the veterinary nurse or technician to create a homecare plan for the patient to ensure appropriate convalescent care is continued in the home environment. This homecare plan could be a simplified version of the care plan example in Table 2, which the owner takes away with them, detailing all information about what procedures have been performed, and what advice and interventions the veterinary nurse or technician wishes to impart on them. For example, the start of the homecare plan may look like that shown in Box 1.

| Sebastian's needs: | What you need to do to help: |

|---|---|

| Sebastian has had teeth removed and his gums stitched up, so this means he might be reluctant to eat his normal dry diet for the first couple of weeks, and we do not want to disrupt the healing process. | Please feed Sebastian with cooked chicken/fish/scrambled eggs, basically a non-sticky food substance, for the next 2 weeks until we have checked his gums have healed up well. |

| As Sebastian has had his front incisor teeth removed, which animals use to groom with, he may not be able to groom himself as well as he used to. He may also find it strange initially while his gums are healing when he tries to groom himself. | Please brush Sebastian once a day (or as often as you like) to maintain good coat condition and remove dead hair. You may have to continue this routine into the future for him. |

| And so on for any remaining problems or aftercare the clients need to provide… | |

Such explicit instructions and advice would undoubtedly improve client compliance with homecare advice, but also ensure they were well informed and involved in the aftercare of their pet, which is ultimately a responsibility the nurse/technician hands over to them at discharge. This may be a little time-consuming to create, but if it encourages optimal healing and educates the clients about oral homecare requirements then it is a worthwhile endeavour. Standard templates could be created for this, and then simply amended to make them patient specific.

If a patient has had teeth saved via endodontic therapies, the post-operative care plan is likely to look a lot different to the example provided in Table 2. Due to there being no extraction sites needing to heal, all actual and potential problems relating to this aspect of the surgery would not apply; the only relevant information from the example would be actual and potential problems associated with anaesthesia and recovery. Pain would be minimal or indeed absent due to minimal tissue disruption and manipulation during the endodontic surgery, and the patient should be able to return to whatever is their normal functioning relatively rapidly.

This means the homecare plan created will also be less involved. It would be advised that information regarding the procedure should still be included from a client education perspective and to reinforce what has been done to save the tooth/teeth, and they should be advised regarding ongoing radiographic monitoring requirements. Standard post-operative care advice would however be sufficient in these circumstances.

Conclusion

Teeth assist animals in performing a number of everyday activities, such as grooming and eating, and some teeth are strategically positioned within the jaws to enable normal physiology and behaviour. This article has highlighted the specific ways in which teeth contribute to normal physiology including the modulation of bite forces, jaw strength and integrity, and also the potential consequences associated with teeth being extracted. It is the responsibility of all veterinary professionals to ensure they examine and assess all animals' oral cavities thoroughly prior to making the decision to extract teeth, and they must be mindful of the potential alternatives to extraction and who they can contact for further advice and guidance. All treatment options should be discussed with owners, allowing them to make an informed decision about the future of their pet's teeth, and referral to a specialist may be the route they wish to take to establish the potential for salvaging teeth rather than losing them.

Key Points

Conflict of interest: none.