Few puppy or kitten owners get through a first vaccination visit at a veterinary practice without hearing the term ‘socialisation’. The owners of older pets may hear veterinary staff or dog trainers, suggesting that the owner takes steps to ‘socialise’ their pet. Yet, what do these terms, being applied to animals of very different developmental stages, actually mean? Are they interchangeable? And, if ‘socialisation’ is a process associated with the early development of the puppy or kitten, is it impossible to improve the social and environmental skills of older animals? These questions are perennially pertinent to pet owners, but possibly more so this year as veterinary practices continue to meet the young dogs and cats that have joined family homes during the spring/summer of the 2020 COVID-19 lockdown, and as many more puppies and kittens join families amidst the COVID-19 social disruptions of the autumn/winter of 2020.

Why do some animals form social bonds with their own and other species?

McMillan (2016) suggested that social animals that form strong relationships and are integrated most strongly into group living are most likely to survive, reproduce, and raise offspring to reproductive age. McMillan also suggested that animals that fail to conform to the social norms of their species may be ostracised by con-specifics (animals of the same species), leading to reduced levels of safety (e.g. from predation), and reduced hunting/foraging success, potentially resulting in their mortality. Sociality, hence, provides benefits such as mutual protection; whereas, social isolation may represent a danger. McMillan suggested that if individual animals are unable (whether as a result of individual circumstances or species-specific preferences) to associate with their own species, there can exist a strong motivation to create a social bond with an alternative social species.

In dogs, an innately social species regarding its con-specifics, it is widely accepted that a consequence of domestication has been a predisposition to form social attachment and dependency on humans, and that within a domestic setting social contact with humans optimises the dog's quality of life (Serpell, 2017). Conversely, cats have no innate requirement for social contact with con-specifics or humans; yet, within the towns and cities of the world, where cats are forced into direct and, often, close contact with other cats and humans, it is clear that the domestic cat's survival is heavily dependent on the presence of humans to provide access to the basic resources that are essential to sustaining existence (Bradshaw et al, 2012). Particularly in domestic environments where the size of the cat population inevitably creates competition for primary resources, a tolerance of, and social competence with, con-specifics and humans becomes an adaptive advantage.

Socialisation versus ‘socialise that dog/cat!’

The term ‘socialise’ merely refers to meeting other social stimuli. The appropriateness of encouraging an animal to ‘socialise’ will be highly dependent on that animal's species-specific sociability and the level of social competence that the animal has developed in earlier life. From the definitions given in Box 1, it can be seen that there is a considerable difference between the attempts of a companion animal's owner to create resilience to a complex domestic world through timely socialisation and habituation, compared with attempts to improve social competencies by forcing an animal to encounter other animals (including humans) within a social environment in which it has little control over the intensity of the social encounter nor does it have the capacity to elect to avoid and escape from the situation. In young animals there is a fine line between socialisation/habituation and sensitisation, the result being dependent on the age at which exposure to the stimulus occurs and the sensitivity/gradual nature of exposure. In older animals, often exposed both suddenly and at a level of intensity that initiates alarm and arousal, the likely result of exposure to novel stimuli or to stimuli previously encountered concurrently with sympathetic arousal, will be further sensitisation. Hence, great care must be taken in the organisation of the socialisation and habituation of young animals to their social and physical environments. Attempts to ‘socialise’ older animals must take into account individual and species-specific social preferences in addition to ensuring that environments are arranged in such a way as to result in habituation rather than further sensitisation.

Box 1.Some definitionsSocialisation is the process by which animals adopt the behaviour pattens appropriate to the social environment in which they live (Mills et al, 2010). This allows them to co-exist and/or interact with other individuals (Figure 1), enabling their social preferences and species identity to develop. Although the adaptability required for socialisation is most amenable during the early development of an animal, with the necessary conditions, the remedial acquisition of socialisation can occur later in life.Socialisation period is the term used to describe the period of an animal's development at which it is most responsive to forming social attachments (Mills, 2010). As the period is intended to enhance the survival of the individual, the specific period will be dependent on the species concerned. Experiments have resulted in the period 3 to 12 weeks (peaking at 8 weeks of age) being accepted for the dog (Mills, 2010), but because of the natural ethology of the cat, the period is considerably shorter — between 2 to 7 weeks of age.Habituation is a form of learning that results in the presentation of a stimulus eliciting no response from an animal. The animal that habituates to the social and inanimate stimuli within its living environment receives a considerable benefit in ‘biological fitness’, no longer wasting energy or engaging sympathetic arousal (and hence a stress response) on exposure to ‘everyday’ stimuli –—reserving such survival and alarm strategies for situations that fall outside their previous experience and that may pose genuine danger. Habituation is most easily established while an animal remains in a para-sympathetic state of relaxation and hence it is best undertaken concurrently with the socialisation period (although the period for puppies can extend slightly to 14 weeks of age (Mills, 2010)).Dishabituation occurs when the effects of habituation to either animate or inanimate stimuli is reversed following further exposure to habituated stimuli concurrent with or immediately following stress-inducing conditions (Mills, 2010), e.g. illness, social isolation (such as following a puppy being housed in kennels), excessive levels of exposure to a stimulus (e.g. sudden, loud noises).Sensitisation occurs when an animal reaches a state of increased reactivity to a stimulus following or concurrent to arousal of positive or negative emotions and their respective stress responses. The result is an increasing likelihood that the animal will respond more rapidly and with greater intensity on future exposure to the stimulus (Mills, 2010). In addition, there will be a greater likelihood of an excessive response to stimuli met immediately subsequent to an exposure to a sensitising event.

Is socialisation the be all and end all of developing sociability?

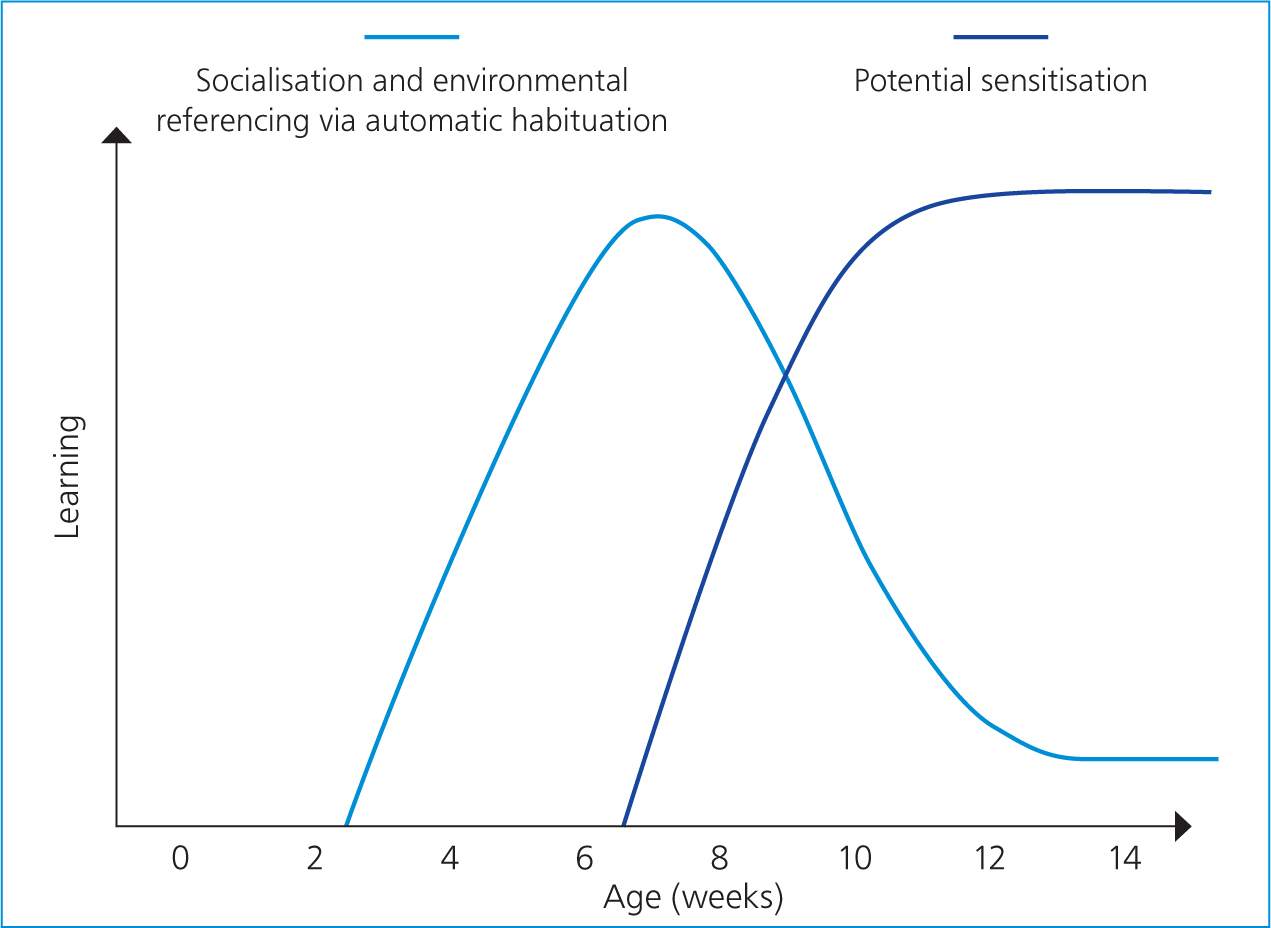

Is sociability assured if a young animal is introduced to social stimuli at the species-specific adaptive period for learning positive associations with social stimuli? Unfortunately, the answer is ‘no’! Even within the socialisation period for dogs, experiments have shown that there is likely to be a period (3–8 weeks) when this will be more effective (Figure 2) than if encounters occur later within the period (8–12 weeks) (Mills, 2010), and there can be breed specific constraints that further reduce the flexibility of these periods. The graph in Figure 2 will be more compact (with socialisation coming to a close at approximately 7 weeks) and displaced to the left when describing kittens.

There are several other factors that can either enhance or impede the socialisation and habituation process (Table 1).

Table 1. Some factors affecting the effectiveness of socialisation and habituation

| Factor | Associated with: |

|---|---|

| Genetics | Breed specific behaviours (including reactivity to the environment), morphology (affecting communication), stimulus salience to the species, individual temperament of parents (Serpell, 2017) |

| Pre-natal environment | Both positive and negative stress-related encounters of the mother can affect the exposure of the developing fetal nervous system to stress-related chemicals (Huizink, 2004) |

| Neonatal and transitional period (i.e. pre-socialisation) | Gentle and gradual exposure to stimuli is essential for the development of organ systems and motor-coordination (Battaglia, 2009) |

| Maternal behaviour | Both the nutritional and emotional state of the mother affects the developing brain, nervous system and future behaviour of offspring (Gazzano et al, 2008; Bray et al, 2017) |

| Complexity of the nest environment | Affecting environmental resilience while alone and problem solving (Appleby and Pluijmakers, 2004) (Figure 3) |

| Provenance of the puppy or kitten | Young animals sourced from breeders who have prepared the animal, through early socialisation and habituation, will be less traumatised on entering their new homes and will be more prepared to learn new positive associations (avoiding dishabituation and sensitisation) (Hunthausen, 2009; Seksel, 2009) |

In addition, there is increasing evidence of the role of epigenetics in explaining the manner in which genes and experience (nature/nurture) interplay to both enhance and hinder the social and environmental competence of animals (Serpell, 2017). Examples are in the manner in which maternal behaviour, physical and emotional stress and exposure to drugs and toxins (both pre- and post-birth) can alter the expression of genes regulating the central nervous system, particularly during the early development of the brain and at the particularly sensitive periods immediately post the socialisation period, during puberty/sexual maturity and during social maturity.

Hence, even with a thorough introduction to the social and physical environment, sensitively applied through gradual exposures that takes into account the young animal's on-going capacity to relax, resilience may not be assured. However, without such timely, thorough yet sensitive introductions to the social and physical environment, future sensitisation is almost guaranteed (Zulch, 2017).

The bottom-line regarding attempts to build resilience in young animals through adequate, successful socialisation and habituation

The owner's aim regarding both socialisation and habituation is to enable the young animal to remain relaxed in its ‘normal’ environment, reserving emotional responses for situations that warrant heightened awareness, arousal and a stress response to create behaviours of approach or avoidance/distance creation. In short, an effective socialisation period creates a concept of safety and coping — the resilience to the ‘normal’ environment and minor changes within that environment, that enables the animal to remain relaxed in a wide range of situations. Although timely arousal of positive emotions can only enhance the welfare of a companion animal, the resulting efforts to approach stimuli may not always be appreciated by owners, e.g. the large breed dog that constantly jumps up to greet people, either in or out of the home. However, there are a range of behaviour problems initiated by a lack of competency with social and environmental stimuli that negatively affect the welfare of companion animals, other animals within their proximity, owners and other humans. Such problems can be associated with a lack of social and environmental competence (Table 2). Added to the range of behavioural manifestations associated with a companion animal's lack of resilience to its environment, is the often less frequently considered range of stress-related health problems experienced by both cats and dogs (Notari, 2009).

Table 2. Some potential problems of the under-socialised cat or dog

| Insufficient, untimely or ill-applied socialisation and/or habituation may result in: | Possible behaviour intended to enhance the animal's concept of security |

|---|---|

| Cat: A lack of social competence with the proximity of cats met or observed either inside or outside the home |

|

| Cat: A lack of social competence with unknown humans |

|

| Cat: A lack of competence with the environment outside the home |

|

| Cat: A lack of competence with the environment (physical or social) within the home |

|

| Dog: A lack of social competency with dogs |

|

| Dog: A lack of social competency with people |

|

| Dog: A lack of competence with the outdoor environment |

|

| Dog: A lack of competence with the social environment within the home |

|

The special challenges to socialisation and habituation raised by 2020

2020 has certainly created extra challenges for companion animals, not least those born or finding a home during 2020. This author is already seeing a rise in the number of very young dogs that are being presented because of their extensive sensitivity to both their social and physical environment, within and outside the home. Not only has this cohort of dogs and cats had to spend their socialisation period and the period of their development that was best suited for environmental habituation, in homes that offered limited variety regarding social stimuli and reduced access to ‘outdoors’, but many have spent this time with extremely busy families where exposure to social stimulation, particularly if opportunities for access to quiet places was limited, may have been less than positive. Immediately following the period of ‘lockdown’, many cats will have suddenly encountered a considerable increase in the outdoor cat population, resulting in a complete destruction of previously established cat-cat ‘time-sharing’ arrangements for outdoor resource sharing. In addition, the summer of 2020 brought with it spectacular thunder and lightening storms that, following an extensive period of reduced exposure to outdoor environmental noises, will have sensitised large numbers of companion animals, both more mature cats and dogs and those that were yet to experience a firework season, potentially creating sound-sensitivities in far greater numbers of companion animals than in previous years.

All-in-all, it is likely that we will find that 2020 was a very poor year for the emotional welfare of the nation's pets.

Is remedial socialisation and habituation effective?

For those young animals that come from poor breeding environments that fail to offer opportunities to initiate the building of resilience (and particularly for kittens, whose socialisation period will have concluded prior to entering their new homes (Zulch, 2017)), remedial habituation may be the only opportunity to create a fulfilling life for a pet. However, bearing in mind the range of effects (Table 1) that may already form a challenge to a young animal's emotional welfare, such remedial building of social and environmental resilience needs to be undertaken with care. Owners undertaking remedial support for their pet need to be fully aware of the essentials for the process, the major one being: aim to never force the animal into a state of ‘failing to cope’. This requires:

- An awareness of how a specific species may indicate that it is becoming uncomfortable with the environment or proximity of a stimulus

- A clear concept of what range of environments and stimuli the pet is likely to encounter in daily life, adding these to any list of stimuli for remedial introduction

- Careful selection of social and physical environments for remedial training, so that complexity and intensity of the social and physical encounters can be slowly built on, only increasing these parameters as the animal becomes competent with less challenging stages

- A willingness to accept that when an animal shows signs of failing to cope, an owner has inadvertently expected too much from their pet, too soon. This is not a fault of the pet — the owner will need to lower their expectations, return to a stage in their ‘plan’ that they know is easy for their pet, and the owner will need to be willing for future encounters to progress more slowly and in smaller, incremental stages.

The above is essential because building resilience is all about building social and environmental competence without initiating emotional responses and their resultant stress responses. However, owners cannot expect their companion animals to be capable of relaxation or learning to relax while outdoors, if the animal leaves the home in a state of stress because of an inability to feel completely safe and secure within the home environment. Hence, owners often require a significant amount of support in creating that initial sense of security and coping within the home, before improvements in competency can begin in the environment outside the home.

With patience, owners can bring about significant improvements in the resilience of their pets through using remedial socialisation and habituation. However, the individual challenges affecting a pet (e.g. those in Table 1 plus previous learning) may prove insurmountable, even with the use of psychotropic support. It is the experience of this author, and, anecdotally that of other clinical animal behaviourists, that for example some of the dogs brought to rescue centres from countries with street or feral populations (Bacon, 2019) and feral cats (Ellis, 2016), are likely to have so little concept of the advantages of associating with humans, and such minimal positive experience of the human domestic environment (possibly combined with challenges in Table 1), that they are incapable of rehabilitation and are hence unsuitable to be kept as domestic companions.

Conclusion

Use of the socialisation period to enhance a young companion animal's social and environmental resilience remains a priority in the behavioural and emotional welfare support that owners can offer their pet. However, it must be accepted that the process involves time limitations and that it will not occur spontaneously without the right level of planning and exposure to social and environmental stimuli. Neither is spontaneous resilience assured even with such opportunities for exposure to stimuli during the socialisation period, as many animals will join their first home with pre-existing and significant challenges to their ability to remain in a para-sympathetic state within the domestic home. As a consequence, young animals intended for a life as a domestic companion rely on the veterinary profession's support in educating breeders, prospective and current owners regarding both the importance and intricacies of the effective use of an animal's early developmental periods, and the sensitive application of remedial support, in creating resilience to the domestic world.

KEY POINTS

- The socialisation period extends the genetic/innate social flexibility of an animal regarding how it interacts with a species, and the range of species with which it will interact.

- The socialisation period is a very specific period of an animal's development — often closed or near to closing by the time that the animal joins its first home.

- The socialisation period overlaps with the prime time for an animal to habituate to (learn to relax with) inanimate stimuli within its environment.

- Due to the inherent complexities of the domestic environment, socialisation and habituation are essential to a companion animal building resilience.

- Both young and more mature animals may have one or more pre- or post-birth challenges to their ability to become resilient to the domestic environment.

- The social disruptions to human activity, associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, are likely to have severely restricted the natural development of social and environmental resilience in young animals.

- With sensitive and informed application, remedial socialisation and habituation is possible in many companion animals.

Useful contacts and information:

- Association for the Study of Animal Behaviour list of accredited Certified Clinical Animal Behaviourists - http://asab.nottingham.ac.uk/accred/reg.php

- The Fellowship of Animal Behaviour Clinicians - https://fabclinicians.org/handouts/

- The Animal Behaviour and Training Council's register of behaviourists can be found at http://www.abtcouncil.org.uk/index/abtc-members-by-region.html

- Blue Cross – Dog: https://www.bluecross.org.uk/pet-advice/choosing-right-dog

- Dogs Trust – Buying a Dog or a Puppy: https://www.dogstrust.org.uk/help-advice/advice-for-owners/buying-a-dog/buying-a-dog

- RSPCA Buying a puppy - https://www.rspca.org.uk/adviceandwelfare/pets/dogs/puppy

- International Cat Care (isfm) – www.icatcare.org

- The Cat Protection Behaviour Team – 01825 741991 – behaviour@cats.org.uk – wwww.cats.org.uk/cat-behaviour