In recent years many advances have been made by the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (RCVS) in respect of the developing profession of veterinary nurses (VNs). This includes the introduction of a non-statutory register of VNs in 2007 and the development of the first edition of the Code of Professional Conduct for Veterinary Nurses (RCVS, 2012a). The register introduced compulsory continuing professional development and from April 2011, disciplinary procedures for registered VNs. Ultimately the goal of those driving the changes in the profession is to achieve statutory regulation for VNs; this would involve the protection of the title ‘Veterinary Nurse’ under law, ensuring that only qualified individuals registered with the RCVS could work under this title (Branscombe, 2011).

In October 2011 an e-petition was launched to bring the subject to the attention of Parliament (HM Government, 2012a). Branscombe (2011), on behalf of the British Veterinary Nursing Association (BVNA), urged members of the veterinary and veterinary nursing profession (VNP) to sign the petition and encourage colleagues to do the same. When the petition closed in October 2012, just over 2500 signatures had been gathered. With 100 000 signatures needed for the issue to be discussed in the House of Commons (HM Government, 2012b), the petition did not achieve its goal. This literature review aims to discuss why the statutory regulation of VNs is important to the veterinary profession and identify the reasons for limited support within the profession.

Literature review

Veterinary nursing as a profession

Currently veterinary nursing may not be completely acknowledged as a profession, key factors could influence this, such as its inability to achieve complete statutory regulation or protection of the title. In 2004, literature was published to determine a working definition for the term ‘Profession’, to aid medical educators. The first half of the definition, illustrated below, sets out the requirements for the recognition of a profession.

‘An occupation whose core element is work based upon the mastery of a complex body of knowledge and skills. It is a vocation in which knowledge of some department of science or learning or the practice of an art founded upon it is used in the service of others. Its members are governed by codes of ethics and profess a commitment to competence, integrity and morality, altruism, and the promotion of the public good within their domain’

When the definition is examined it can be determined that veterinary nursing has been able to parallel its requirements with the Code of Professional Conduct for Veterinary Nurses (Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, 2012a) and profess their commitment with the declaration taken on registration. Further to this, veterinary nursing has achieved criteria equivalent to that needed to be part of the Health and Care Professionals Council (HCPC, 2012), such as practice based on evidence and standards in conduct, performance and ethics. The HCPC regulates numerous public healthcare professions, including radiographers, paramedics and physiotherapists.

Reasons for statutory regulation of the VN

The key reasons that statutory regulation of VNs is being sought include: protection of the public and ultimately the protection of patient's welfare under the care of qualified VNs (Jeffery, 2010). A VN's acceptance of the responsibility for animal welfare is seen throughout laws and codes relating to the profession, as discussed below.

Since 2012, every newly qualified VN makes a declaration on admission to the professional register, in which they promise to ‘ensure the health and welfare of animals’ committed to their care. This statement is seen again in the Code of Professional Conduct for Veterinary Nurses (Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, 2012a). This responsibility for welfare is also seen in The Animal Welfare Act (2006) section three, which states that a person is responsible for an animal whether on a permanent or temporary basis; this applies to qualified VNs in practice.

The public are increasingly aware of their rights as consumers and advances in technology have allowed instant access to information such as reviews and news reports, which could affect practices and the profession. The profession was reminded of this with the release of Panorama's ‘It shouldn't happen at a vets’ (British Broadcasting Corporation, 2010), which identified unqualified staff, although legally, working under the title of Veterinary Nurse. Despite ease of access to information, it is suggested that the public lack knowledge of the role and skills of qualified VNs (Branscombe, 2012).

Regulation of VNPs abroad

The Republic of Ireland regulates its veterinary profession through the Veterinary Council of Ireland (VCI), registration with the VCI is required to work under the title of Veterinary Nurse in Ireland (VCI, 2012) as instructed by the Veterinary Practice Act (2005). Each VN must follow the VCI Code of Professional Conduct for Veterinary Nurses (VCI, 2011) and achieve a minimum of 12 credits in continuing veterinary education over the period of a year. Credits are allocated depending on the method and hours of continuing veterinary education undertaken.

Regulation of public healthcare in the UK

Regulation of nurses in public healthcare in the UK has been present since the establishment of a nonstatutory register in 1887, and statutory regulation did not occur for general nursing until 1919 (Nursing Registration Act, 1919), 30 years after the development of the voluntary register. Nurses and midwives are currently regulated under their own professional body, The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) as instructed by The Nursing, Midwives and Health Visitors Act 1997 (Nursing, Midwives and Health Visitors Act, 1997; Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2010).

Public healthcare nurses’ professional responsibilities are guided by The NMC Code of Conduct (Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2008) which has similarities with the Code of Professional Conduct for Veterinary Nurses (Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, 2012a). These codes include that care of patients (or the health and welfare of animals) should be the first concern of nurses or VNs. Like the Code of Conduct for Veterinary Nurses (Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, 2012a), The NMC Code of Conduct covers subjects on competence, confidentiality, consent, delegation, record keeping, impartial advice and upholding the profession. This code may provide guidance for future developments in the regulation of the VNP.

Support for statutory regulation from the veterinary profession

The support of VNs and veterinary surgeons working within the profession will have a substantial influence over the progress in regulation of veterinary nursing, as they can extend their attitudes to others. In 2011, just over 34 000 veterinary surgeons and VNs were registered with the RCVS (Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, 2012b). Examining the legislation that was identified in this literature review, in relation to upholding duty to animal welfare, it could be hypothesised that these professionals would support regulation. However with 2500 signatures on the e-petition to regulate VNs under statute, this equates for approximately 7% of the joint profession. It is important to identify if and why there is a lack of support within the profession, to be able to make improvements.

In May 2012 a veterinary surgeon's letter, opposing the statutory regulation of VNs and the protection of the title, was published in the Veterinary Times (Zakharova, 2012). The veterinary surgeon refused to support the title restriction until recognition was given to unqualified persons working under the title of Veterinary Nurse. Zakharova (2012) misunderstood the reasons for restriction of the title, believing that it protected VNs interests, instead of animal welfare. Partridge, another veterinary surgeon, mistook the regulation of VNs as a method of increasing the number of Schedule 3 activities (of the Veterinary Surgeons Act) which VNs could undertake (Partridge and Badger, 2010; Veterinary Surgeons Act, 1966).

Wyse (2012), a new graduate veterinary surgeon who supported veterinary nursing regulation, replied to the letter by Zackarova (2012) noting that unqualified VNs have often lacked underpinning knowledge. With a belief that the title should be protected she made the point that, ‘We (veterinary students) receive very little training with VNs and almost nothing on what qualified VNs are trained to do’ (Wyse, 201: 23). It can be argued that Wyse (2012) would be unable to identify the required knowledge of a VN, as the veterinarian admitted a lack in training in the subject.

Conclusion of the literature review

The literature supports the notion that VNs should be regulated by statute to protect animal welfare and the interests of the public. A credible example to guide veterinary nursing regulation would be that of the VCI, which prevents those not registered with the regulatory body from practicing under the title of Veterinary Nurse.

The evidence collected suggested that veterinary surgeons’ knowledge and support of the VNP may have been minimal due to a lack of education on the subject. Having an understanding of the professional status of VNs will allow newly qualified veterinary surgeons to confidently and correctly delegate Schedule 3 activities (of the Veterinary Surgeons Act, 1966), uphold the declaration taken on registration and follow the Code of Professional Conduct for Veterinary Surgeons (Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, 2012c). Team work may also be more efficient with an improved understanding of each other's roles.

An improved understanding among veterinary surgeons is indispensible to the progression of the VNP as a whole, in practice this may lead to more job satisfaction for VNs through the points discussed above and employment may become more economical with VNs being used to their full capabilities. Outside of the work environment veterinary surgeons may be encouraged to become involved in and advocate for the future development of the VNP.

Therefore research was conducted into student veterinary surgeons’ (SVS) knowledge and support for VNP regulation and how this related to their studies at each UK veterinary institution, using the hypotheses listed below.

Methodology

The population of SVS studying in their final year (2012 to 2013) in the UK were chosen to take part in the survey (n=840). This population was chosen as SVS from earlier years of study may not have received formal education on the VNP. A questionnaire was piloted on a population of 21 recent veterinary graduates from the Royal Veterinary College and Bristol University. A final descriptive questionnaire was then distributed to the population of SVS through their institutional email addresses. Of the population it was hoped that a 20% response rate would be achieved to ensure a reliable sample (n =168).

This study was approved by the Royal Veterinary College ethics committee and was ethically reviewed and approved by the University of Edinburgh, University of Liverpool and University of Bristol before being released to SVS. The three remaining universities granted the survey to be sent to SVS without undertaking their own ethical review. Responses were confidential, consent was given for collection of the data and respondents could withdraw from the study if they wished.

To evaluate hypotheses one and two, nine closed ended questions were asked to obtain a ‘knowledge score’ of the VNP. These questions included the topics of: Schedule 3 (amendment 1991) of the Veterinary Surgeons Act 1966; VNs’ responsibilities for their actions; veterinary nursing regulation and disciplinary jurisdiction. A figure was given to the respondents for correctly answered questions, this became the knowledge score. To evaluate hypothesis 3 a ‘support score’ was obtained by asking if respondents supported statutory regulation of VNs and restriction of the Veterinary Nursing title, figures were assigned depending on their responses. Results were entered into Excel (Microsoft, 2010) and imported into Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS, IBM, Statistics 20) for data analysis. Hypotheses were tested using the independent samples T test, Mann Whitney U test and Kruskal Wallis test. Significance was taken at p≤ 0.05.

Results

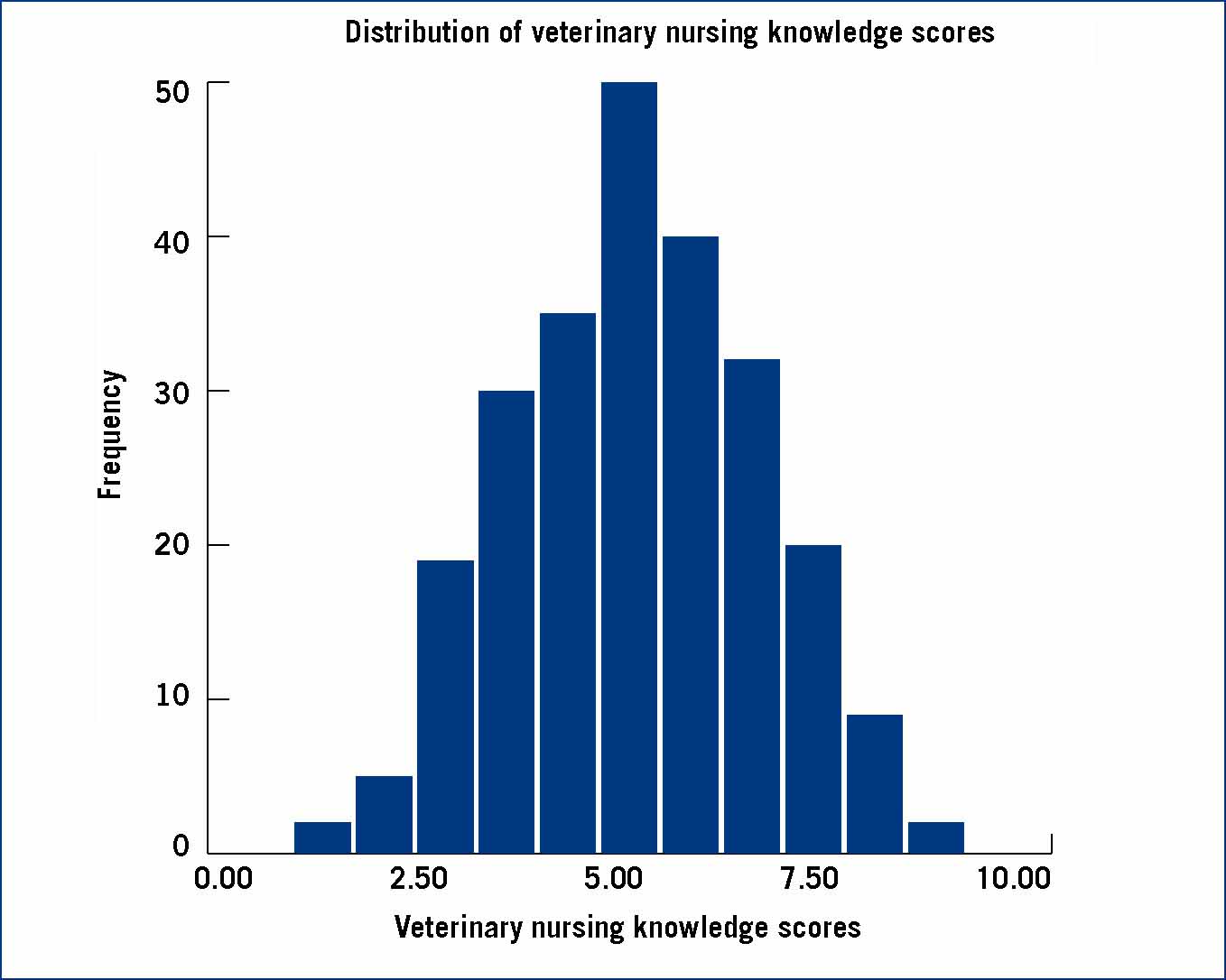

Overall 245 (response rate of 29%) respondents completed the final online survey. 117 (47.8%) respondents studied at universities that also offered veterinary nursing courses and 128 (52.2%) respondents studied at universities that did not. The mean veterinary nursing knowledge score was 6.1 (standard deviation of 1.96) (Figure 1). The median veterinary nursing support score was 2 (minimum 0, maximum 2).

For hypothesis one the Kruskal-Wallis test revealed the difference in veterinary nursing knowledge scores at the seven veterinary institutions was not statistically significant (p = 0.26). For hypothesis 2, an independent-samples t-test revealed no significant difference in knowledge scores of respondents attending universities with or without veterinary nursing courses (p = 0.207). A Mann-Whitney U Test revealed a statistically significant difference in student support scores at universities with (Md = 2) and without (Md = 2) veterinary nursing courses (p = 0.016). Cohen's effect size indicates a small effect (r = 0.15).

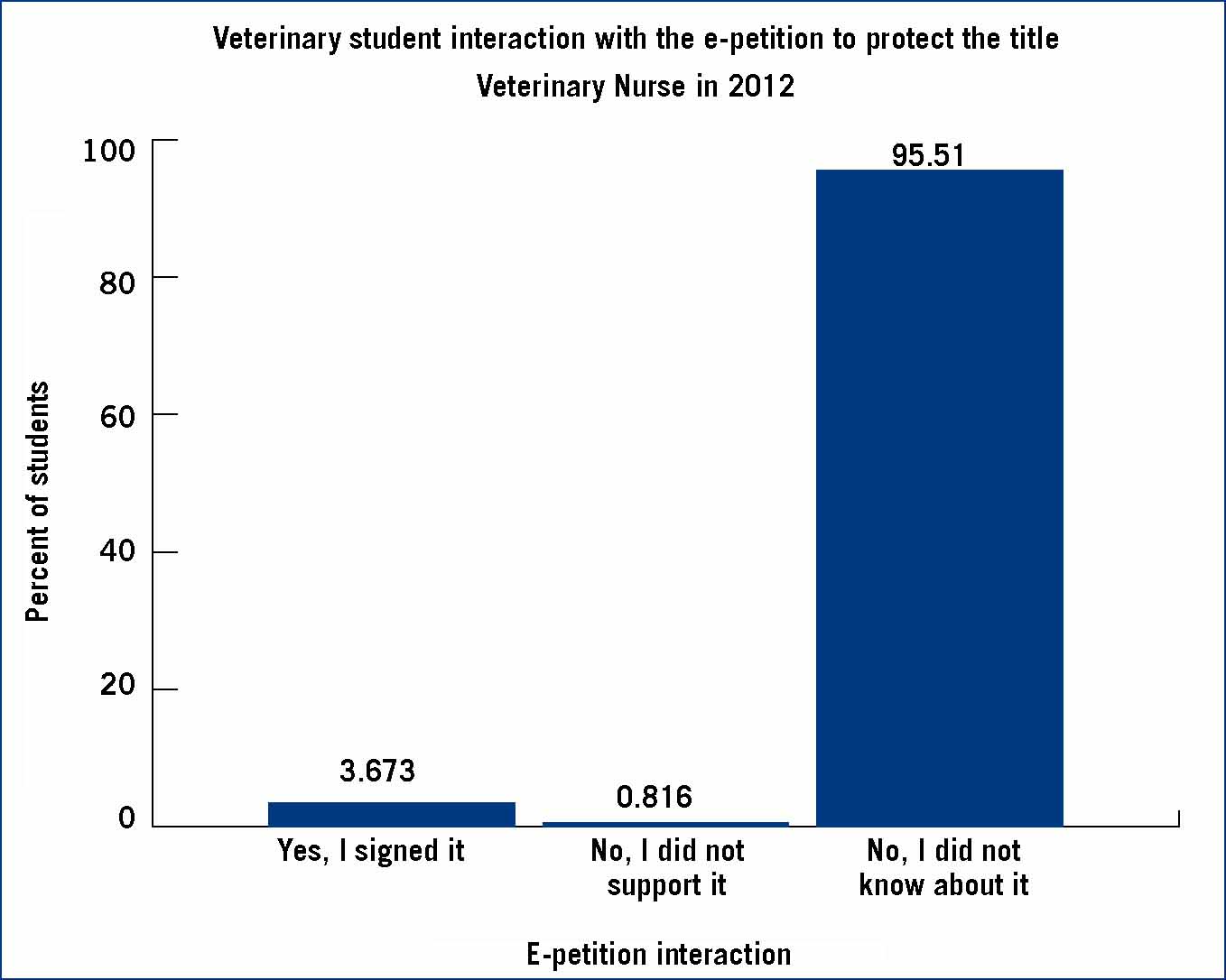

In regard to the e-petition to restrict the title Veterinary Nurse, nine (3.7%) respondents signed the petition, two (0.8%) did not sign the petition as they did not support it and 234 (95.5%) had no knowledge of the petition (Figure 2). Of respondents 240 (97.96%) agreed that VNs should be regulated by law and 236 (96.33%) respondents agreed that the title of Veterinary Nurse should be restricted to those with the appropriate qualifications and registration.

Discussion

Hypotheses one and two were disproven by the data collected, therefore the university attended or the presence of a veterinary nursing course, does not influence SVS knowledge of veterinary nursing. Knowledge scores for the VNP were evenly distributed amongst the population of final year SVS. Hypothesis three was proven (p=0.016) and therefore SVS support scores differ significantly between universities offering veterinary nursing courses and those that did not. A suggested reason for increased SVS support at universities with veterinary nursing courses is that with recent encouragement of interprofessional learning, the SVS would have increased awareness of the VNP (Branscombe, 2010).

The study looked briefly into how the respondents interacted with the BVNA e-petition to protect the Veterinary Nursing title in 2012 (HM Government, 2012a), which closed to signatures 1 month before this research commenced. The majority of respondents had no knowledge of the petition, although all involved in the veterinary profession were urged to sign the petition (Branscombe, 2011), suggesting the appeal was unsuccessful in reaching the whole veterinary profession. Despite this, findings are encouraging, as the majority of SVS supported development of the VNP.

After the initial review of literature for this report the RCVS announced a proposal for the future statutory regulation of VNs (Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, 2013) under the RCVS. The regulatory proposal includes removal of the list of VNs, preventing those struck off the register of VNs from performing Schedule 3 activities of the Veterinary Surgeons Act 1966 (Veterinary Surgeons Act, 1966). Additionally during the research period, the first registered VN was removed from the register as a result of ‘dishonesty and a failure to maintain accurate records’ (Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, 2013). This has professional importance as this individual will still legally be able to practice under the name of Veterinary Nurse until new legislation is in place.

The study could have been improved by including data from qualified veterinary surgeons; however this may have proved difficult as specific literature on qualified veterinary surgeon support and knowledge of the VN profession was limited. To the best of the authors’ knowledge no similar study had been conducted on the SVS of the UK.

Possible future study

The research recognised a need to identify knowledge of and support for the VNP within the population of qualified veterinary surgeons. Identifying what variable affects a veterinary surgeons support for the profession and whether this occurs in earlier or later stages of training may also be valuable.

Conclusion

It can be concluded that SVS knowledge of the VNP is evenly distributed in the population of UK final year SVS, and this is not influenced by the university a SVS attends or the presence of a veterinary nursing course. The presence of a veterinary nursing course at a university increases a SVS support for the VNP, and overall veterinary student support for the VNP is high.