Events in 2020 were overtaken by the global COVID-19 pandemic and the veterinary industry was no exception. Focus was drawn away from exotic parasites and replaced with concerns about a resurgence in domestic parasite infections following a reduction in routine parasite control. In 2021 this trend still continues and we are seeing new themes such as environmental contamination come to light.

Key themes and hot topics

This time last year, the key themes were:

- Angiostrongylus vasorum lungworm and reduced routine preventative treatment amidst COVID-19 restrictions

- Giardia spp.

- Domestic parasites.

So far in 2021 the key themes are:

- Environmental contamination from flea control products

- Imported dogs and exotic parasite infections

- Tapeworms, pet travel and Brexit.

The hot topics in 2020 came as a surprise to everyone. Focus was expected to be on exotic parasites as was the trend for all previous years, but instead things took a U-turn after oversees travel largely stopped because of the COVID-19 crisis. Instead, we saw a renewed interest in domestic parasites, especially Angiostrongylus vasorum, dog tapeworms (Echinococcus granulosus), Giardia spp. and Toxocara spp. (Figures 1–4).

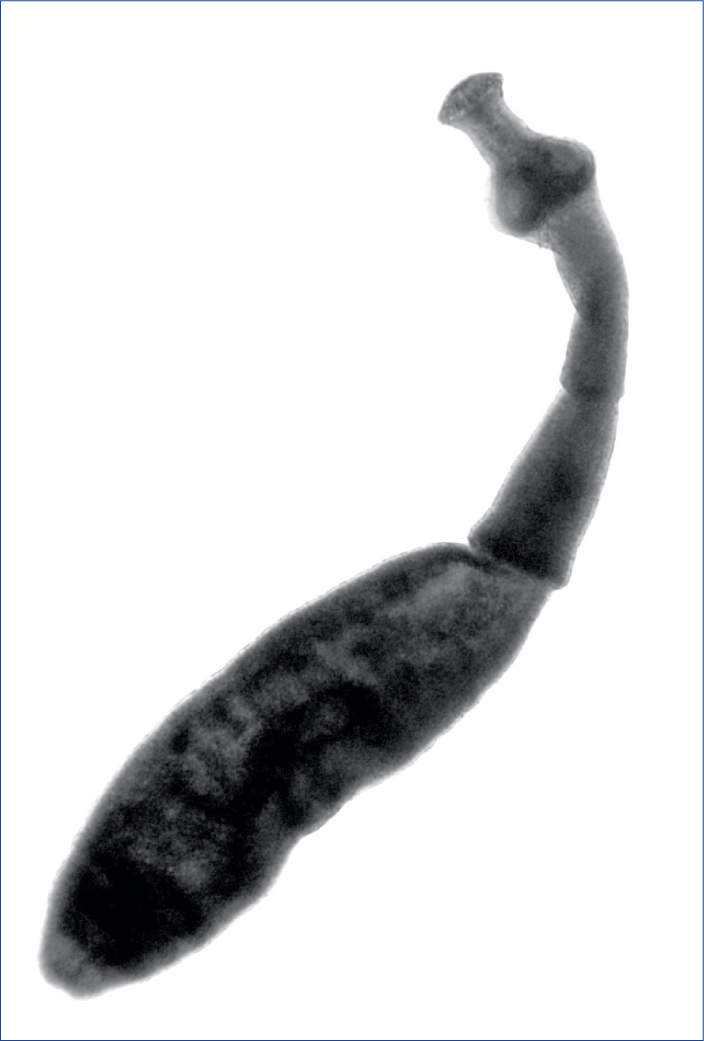

This time last year, we were mid first lockdown. But before this, life was mostly continuing as normal for many of us. A wet and mild winter and spring resulted in an influx of giardiosis which continued all the way into summer until we had a significant warm dry spell to stem the infection rates. As we went into lockdown, most veterinary practices adapted and implemented systems to manage appointments with social distancing and the ongoing supply of medications throughout lockdown. Despite this, many pet owners were reluctant to visit their veterinary surgeon or register new puppies with a veterinary practice. With many people getting puppies for the first time during lockdown, this meant that no parasite prevention plan was set up for many puppies. This has had ramifications for all domestic parasites, but A. vasorum lungworm was of particular note when an increase in angiostrongylosis was seen as a result (Figure 1). A published study has shown a continuing lack of awareness by dog owners about A. vasorum and the risks it poses to their dogs, with only half of dog owners aware of lungworm and only 13% actually knowing what it is (Woodmansey, 2019).

Environmental contamination from flea control products

Environmental contamination from flea products is a topic that was first picked up towards the end of 2020 following an article that identified that some insecticides have caused environmental contamination. After fipronil and imidacloprid contamination was found in UK waterways, there were strong suggestions that the source may be flea prevention products. Perkins (2020) discussed this contamination, noting the need for more research to establish to what extent companion animal flea products do contaminate the environment. Suggestions are that products may be contaminating waterways via pet bathing, swimming and washing of items (Perkins, 2020). Further research is needed into all potential sources of waterway contamination including, but not limited to, the veterinary industry. ESCCAP UK & Ireland held a roundtable discussion in March 2021 with parasitology and environmental experts to explore these issues and find areas of consensus, the results of which will be published this summer.

Imported pets and exotic parasite infections

As international travel ceased during 2020, it was thought this would give the UK a break from the threat of exotic parasites. Instead, attentions were turned to domestic parasites. However, lockdown proved the perfect opportunity for many people to purchase or adopt a dog as so much time was being spent at home. As animal welfare is such a hot topic, many people turned to rescue organisations, both in the UK and abroad, to find their perfect pet. During lockdown, the UK saw large numbers of rescued cats and dogs imported from abroad and the numbers of dogs entering the country with heartworm and Leishmania infantum infections rapidly increased throughout 2020.

2021 is following the same trend and imported heartworm and Leishmania spp. cases from a wide variety of countries both inside and outside Europe continue to be reported to ESCCAP UK & Ireland. As well as heartworm and L. infantum, imported pets can harbour a wide range of parasites including tick-borne pathogens, Mesocestoides spp., Dirofilaria repens, Thelazia calliapeda and Brucella canis. Many of these parasites are zoonotic with the potential for establishment in the UK. Of particular note for zoonotic risk is Brucella canis, a Gram-negative proteobacterium, especially with regards to the risk to veterinary professionals coming into contact with infected dogs in practice, as well as new owners and charity workers. It is vital that veterinary surgeons and nurses remain vigilant for clinical signs that might indicate exotic parasite infection and that relevant screening tests are carried out for all imported dogs to ensure early diagnosis of all exotic disease (Figure 5).

Tapeworms, pet travel and Brexit

Lockdown has brought into focus the importance of routine parasite control, especially for fleas (Figure 6) and roundworm, as many vulnerable people have been forced to self-isolate in their homes, often with their pets. Even as lockdown ends, many elderly and vulnerable pet owners will spend a disproportionate amount of time indoors, putting them at higher risk of contracting zoonotic diseases such as toxocarosis and bartonellosis from their pets. However, flea infestations and concern about disease transmission should not be allowed to destroy the human–animal bond and so an effective parasite control strategy should be in place for all pets.

There has been a renewed interest in dog tapeworms in the UK, including risk assessments, the use of preventative treatments and also the compulsory tapeworm treatment required to travel to and from Northern Ireland to the rest of the UK. There is currently no part of the UK or Ireland that is endemic for Echinococcus multilocularis, and so there are concerns the mandatory treatment will result in over treatment given the frequent travel of dogs between the two areas. However, tapeworm treatment is a legal requirement at present, but will need renegotiating as further pet travel rules are discussed.

As Brexit legislation continues, exotic disease screening needs to be considered in any reshaping of pet importation. ESCCAP UK & Ireland continue to recommend four key steps (the ‘four pillars’) in all imported dogs. These are:

- Checking for ticks and subsequent identification

- Treating dogs with praziquantel within 30 days of return to the UK in addition to the compulsory treatment, and treating for ticks if a tick treatment is not in place

- Recognising clinical signs relevant to diseases in the countries visited or country of origin

- Screening for Leishmania spp., heartworm and exotic tick-borne disease in imported dogs.

The RSPCA and ESCCAP UK & Ireland have published protocols for assessing cats imported into the UK as rescues from abroad (Whitfield and Wright, 2020). While imported rescue cats are not as common as dogs, there is still the possibility of them introducing exotic pathogens that may affect them, their new owners and UK biosecurity. A consistent approach of clinical examination and testing can help to recognise exotic infection early and appropriate monitoring or treatment implemented.

ESCCAP UK & Ireland enquiry data

Each year, ESCCAP UK & Ireland provide an enquiry answering service for the public and produce quarterly reports of the topics raised in order to identify possible trends.

January to March 2020 (Q1) saw a big change in trends with domestic parasites topping the chart for the first time. Over 16% of Q1 2021 enquiries were regarding A. vasorum lungworm. The reduction in exotic parasite enquiries was likely related to the drop in foreign travel associated with the COVID-19 outbreak and less travel over the winter period. April to June 2020 (Q2) continued to have a domestic focus, with ticks, fleas, A. vasorum and Toxocara spp. roundworm dominating the enquiry chart. The sudden increase in tick enquiries may have been associated with tick bite awareness week and the increase in tick activity seen at this time of year.

In 2021, focus has remained with domestic parasites, especially flea control and the selection of flea products to minimise environmental contamination. Other areas of interest are dog tapeworms, both endemic and exotic and imported exotic parasites.

About ESCCAP UK & Ireland

ESCCAP UK & Ireland is a national association of the European organisation ESCCAP and brings together some of the UK and Ireland's leading experts in the field of Veterinary Parasitology. ESCCAP UK & Ireland provides country relevant information to veterinary and animal care professionals and pet owners in order to raise awareness about the parasite situations relevant to the UK and Ireland and to help protect against pet parasites. For more information please visit www.esccapuk.org.uk.

ESCCAP UK & Ireland is kindly supported in 2021 by IDEXX laboratories, Vetoquinol, MSD Animal Health and Elanco Animal Health.

Conclusion

The year 2020 did not turn out the way anyone expected and so far 2021 is proving just as hard to predict. The interest in domestic parasites is not going anywhere and it is vital that efforts are made to maintain routine parasite control programmes. Although so many fewer pets have been travelling abroad, the effects of imported exotic diseases are still being noted which emphasises the need for all travelled or imported dogs to be screened on arrival (back) in the UK. If legislation and control measures can be put in place during this quiet time of travel then we will be better prepared when the boarders reopen and pet movement increases once again.

Key points

- Increasing numbers of exotic pets are being imported to the UK bringing exotic disease with them.

- Domestic parasites are being favoured by fewer routine preventative treatments being administered as a result of COVID-19 restrictions.

- As fewer pets have travelled abroad on holiday since 2020 we have seen a renewed focus on enquiries regarding domestic parasites.

- Research on environmental contamination with insecticides has reignited concerns around potential contamination with flea control products.