Good nutrition is believed to be fundamental in promoting a state of wellbeing, prolonging life and preventing diseases in companion animals. Nutrition can also be used to help manage animals with various medical problems. In human healthcare, the importance of leading a healthy lifestyle and making good dietary choices are the focus of many public awareness campaigns (Michel, 2006). As people are pursuing healthier lifestyles and being very selective in what they eat, some are demanding the same assurances for their pets. To many people, feeding their pet is considered an expression of love and care with many owners using their own preferences to influence the food selection and feeding practices of their pet (Wakefield et al, 2006).

In recent years, there has been growing interest in the feeding of unconventional diets such as raw, vegetarian and home prepared diets to companion animals (Michel, 2006; Handl, 2014). BARF diets, often referred to as ‘Biologically Appropriate Raw Food’ or ‘Bones And Raw Food,’ were popularised by Billinghurst in 1993. Such diets typically consist of 60–80% raw meaty bones and 20–40% a wide variety of foods including fruit and vegetables, offal, meat, eggs, or dairy foods. In contrast, the ‘prey model diet’ is designed to resemble the presumed diet of carnivorous ancestors of dogs and involves consumption of whole prey, including organs, bones and muscle (Figure 1).

Prior to domestication, the diet of dogs and cats consisted largely of raw food. Once cohabiting with humans, raw food remained the staple diet for cats whereas dogs survived on by-products of human consumption, i.e. table scraps (Weeth, 2013). The nutritional inadequacy of these diets is cited as being responsible for the shortened life span and nutritionally-related digestive, musculoskeletal problems encountered at that time (PFMA, 2010). Yet, current justification for the feeding of this diet stems from the belief that these species are healthier when fed as if still in the wild.

This article explores the nutritional adequacy and food safety issues related to feeding raw meat-based diets to companion animals and considers approaches for communicating with pet owners about the concerns regarding these unconventional diets.

Raw food diets: purported benefits and risks

In developed countries, the categorisation of raw meat-based diets as ‘unconventional diets’ is testimony to widespread availability and use of nutritionally complete, and balanced manufactured diets (Berschneider, 2002; Weeth, 2013) with an estimated 90% of dogs and cats in developed countries consuming complete and balanced manufactured pet foods for at least half of their diet (Laflamme et al, 2008). Such dietary advancements are cited as a contributory factor in the reduction of nutritional-related health issues and increased longevity (Rahaman and Yathiraj, 2000). The popularisation of processed foods has also been suggested as a possible explanation to the increased prevalence of diseases such as diabetes mellitus, however, other factors such prolongation of life, increase in obesity and decreased physical activity may also explain these trends (Rand et al, 2004; Zoran and Rand, 2014). The feasibility that raw meat-based diets can meet the criteria for being complete and balanced is questioned by veterinary nutritionists although unsubstantiated claims by proponents allege that via unique feeding regimens, a balanced diet is achieved over a prolonged period of time as opposed to on every meal.

Whether due to concerns over health and safety, difficulties interpreting food labels or a perceived lack of a suitable commercial pet food product, homemade and commercial raw diets are growing in popularity (Cave and Marks, 2004; Remillard, 2008; Freeman et al, 2013a). Reported motivations for feeding a raw diet can be multifactorial and include:

As with all aspects of patient care, an evidence-based approach to decision making should be used wherever possible, however scientific evidence to corroborate raw food diets is lacking. Proponents of feeding raw meat-based diets, including some veterinary health professionals, support the use of these diets to achieve good health including a healthier coat quality, reduction in dental disease and elimination of halitosis. Anecdotal reports make claims that raw meat-based diets can successfully control a number of medical conditions including chronic urinary, digestive, allergic and metabolic disease (Stogdale and Diehl, 2003). A study conducted in the USA and Australia by Laflamme et al (2008) revealed that 98.7% of dog owners and 98.5% of cat owners considered their pet to be healthy. 16.2% of dogs and 9.6% of cats were fed bones or raw food as a component of their main meal. An analysis of the relationship between owners' perceptions of health with diet was not performed yet it can be assumed that the majority, if not all animals fed this diet, were considered healthy by their owners. Yet claims that raw feeding is nutritionally superior to processed foods are unfounded and the nutrient content, digestibility and benefits to health remain largely unknown.

The near impossible challenge of balancing and ensuring completeness in raw meat-based diets is highlighted by Freeman and Michel (2001) whose study analysed five raw food diets (two commercially produced and three homemade) for nutritional adequacy, and demonstrated a number of nutrient deficiencies and various imbalances with potentially serious health implications. The results of this study were dismissed by advocates who argued the validity of these findings in light of the limited sample size and lack of long-term evaluation on health of the animals fed those diets (Gaston, 2001; Johnson and Sinning, 2001).

Nutritional deficiencies and nutrient imbalances can go undetected for months or even years before any clinical manifestation becomes apparent (Chandler, 2014); yet these diets can have serious implications for younger animals, even when fed for only a short period. A published case report by Taylor et al (2009) in which an 8-month puppy developed osteopenia and myelopathy further illustrates the risks of feeding raw meat-based diets during ‘critical’ periods such as growth when animals are experiencing high nutritional demands (Freeman and Michel, 2001). Further published case reports raise additional concerns regarding the nutritional inadequacy of these raw meat-based diets and the development of clinical problems including hypervitaminosis A, pansteatitis, nutritional osteodystrophy, osteomalacia and nutritional secondary hyperparathyroidism (Niza et al, 2003; Polizopoulou et al, 2005; Dillitzer et al, 2011; Verbrugghe et al, 2011).

Anecdotal reports highlight further risks including dental fractures, intestinal perforations and obstruction related to feeding raw meat-based diets but the overwhelming concerns centre on the risk of pathogens and foodborne illnesses. Proponents of raw feeding allege that dogs and cats are immune to such pathogens (Billinghurst, 1993). However, there are numerous reports confirming food-related infections from both raw foods and manufactured diets due to Salmonella, Escherichia coli, Neospora, Toxoplasma, Campylobacter and Cryptosporidium spp. in dogs (Joffe and Schlesinger, 2002; Stiver et al, 2003; Weese et al, 2005; Strohmeyer et al, 2006; Schotte et al, 2007) with young and immunosuppressed animals at an increased risk of illness and death (Weeth, 2013). It is important to note that animals fed a contaminated raw meat diet can also serve as a source of household environmental contamination posing a public health risk, particularly for the young and immunocompromised individuals (Yin, 2007; Remillard, 2008; Finley et al, 2006).

Evaluating the evidence

To truly offer a balanced and informed analysis of the evidence on the potential risks and benefits of feeding raw meat-based diets would require the availability of data from high quality studies. Unfortunately there is very little data available to formulate a balanced analysis. Much of the information used to support one view or another on the merits and dangers of feeding raw meat-based diets are based on low quality studies composed of anecdotal reports, case reports and case series (Freeman and Michel, 2001;, Taylor et al, 2009; Dillitzer et al, 2011; Freeman et al, 2013a, Freeman et al, 2013b). On the major issue of safety related to bacterial contamination, the evidence is more robust and more numerous (Weese et al, 2005; Strohmeyer et al, 2006; Finley et al, 2007; Buchanan et al, 2011; Nemser et al, 2014), but comparative studies on the impact on the health of domestic animals that consume raw meat-based diets are still lacking.

From a nutritional completeness point of view the major concern with raw meat-based diets is the presence of nutrient deficiencies and excesses. To date, there are only a small number of studies that have attempted to analyse raw meat-based diets for nutritional completeness (Freeman and Michel, 2001; Taylor et al, 2009; Dillitzer et al, 2011). In each of these studies important imbalances have been identified (Freeman and Michel, 2001; Taylor et al, 2009; Dillitzer et al, 2011) that could have serious implications for growing animals in particular. In the study by Dillitzer and colleagues (2011) where the recipes for raw meat-based diets provided by pet owners were analysed for completeness and balance, there were major imbalances found in 60% of recipes studied which does suggest that it is possible to formulate a raw meat-based diet that meets nutritional requirements, but that there are problems in most of these diets. It is also worthy to note that despite the identification of nutritional imbalances in many of these diets, there are only three reports (Taylor et al, 2009, Kohler et al, 2012, Sontas et al, 2014) that could link the unbalanced diet with a clinical problem (e.g. rickets, hyperthyroidism). As the trend for feeding these diets grows, more nutrition-related problems may be reported. Difficulties in ensuring a complete and balanced raw meat diet can be overcome with the provision of comprehensive advice and education from the veterinary healthcare team.

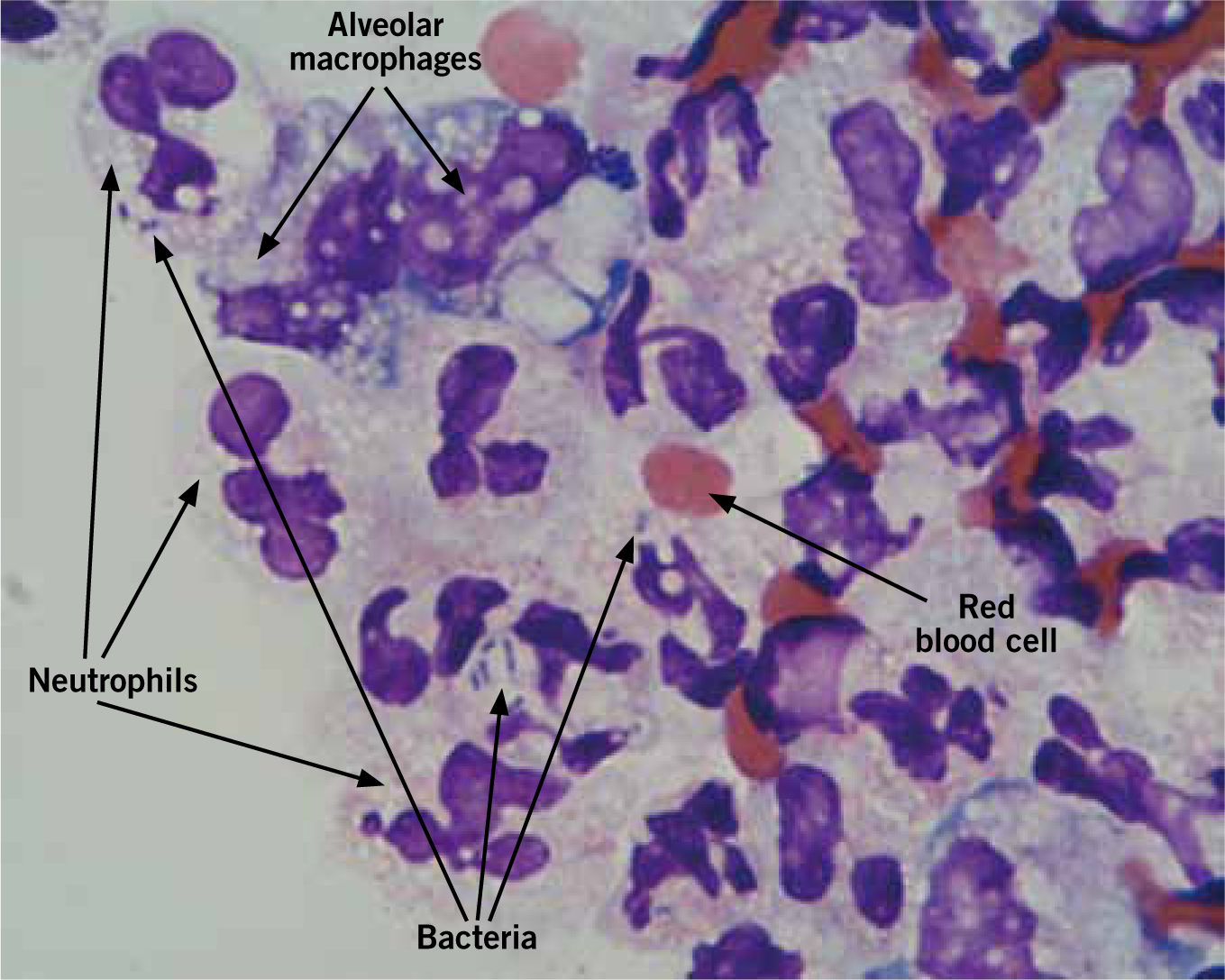

As already alluded to, the major concern with raw meat-based diet centres on bacterial contamination of the diet and the risk posed to both pets fed these diets and the pet owners that use this approach to feeding their pets (Figure 2, Table 1). Contrary to claims made by some authors (Billinghurst, 1993), dogs and cats are not immune to food-borne pathogens (Chengappa et al, 1993; Stiver et al, 2003; Morley et al, 2006; Selmi et al, 2011). A number of studies have clearly demonstrated the risk posed by raw meat-based diets (both home prepared and commercially available) by culturing pathogens from these diets (Freeman and Michel, 2001; Weese et al, 2005; Strohmeyer et al, 2006; Finley et al, 2007; Nemser et al, 2014). Of increasing concern is the presence of pathogens that pose a zoonotic risk and how pets fed raw meat-based diets are being implicated in spreading these pathogens in home environments (Sato et al, 2000; LeJeune and Hancock, 2001; Finley et al, 2006; Weese and Rousseau, 2006; Finley et al, 2007; Lefebvre et al, 2008; Leonard et al, 2011). Further repercussions have been highlighted in a recent study by Schmidt et al (2015) in which a group of healthy, non-antimicrobial-treated Labrador dogs were found to be carriers of multi-drug resistant bacteria, with the consumption of a raw meat diet identified as the main risk factor. Such findings reiterate the potential zoonotic and animal welfare risk. Given these serious concerns, it is vital that pet owners that opt to feed raw meat-based diets are made aware of the risks to both their pets and their families and the veterinary profession has a duty to provide guidance and support in reducing these risks. However, currently, there are no evidence-based guidelines to ensure risk reduction should owners opt to feed raw meat-based diets.

| Test | Result | |

|---|---|---|

| CULTURE | Moderate, mixed growth of 1. Beta haemolytic Escherichia coli and 2. Pseudomonas spp. Isolate 2: Pseudomonas aeruginosa | |

| SENSITIVITY | 1 | 2 |

| Enrofloxacin | S | R |

| Amoxycillin/Clavulan | S | R |

| Ampicillin | S | R |

| Amikacin | S | S |

| Carbenicillin | S | R |

| Cefovecin (Convenia) | S | R |

| Cefsulodin | R | R |

| Ceftazidime | S | S |

| Cefuroxime (Zinacef) | S | R |

| Cephalexin (Ceporex) | S | R |

| Chloramphenicol | S | R |

| Ciprofloxacin | S | S |

| Clindamycin | R | R |

| Gentamicin | S | S |

| Imipenem | S | S |

| Marbofloxacine | S | R |

| Oxytetracycline | S | R |

| Pradofloxacin | S | R |

| Sulphonamide/Trimeth | S | R |

Communicating with clients

Veterinary nurses (VNs) and technicians play a key role in the provision of nutritional intervention and often provide an initial point of contact for clients when it comes to dietary advice. With the plethora of nutrition-related information available to pet owners, combined with recent pet food recalls and a growing interest in raw and unconventional feeding practices, it is essential for veterinary nursing practitioners to evaluate and discuss a diet's suitability with clients. However, the scope of advice given should be in accordance with the VN's knowledge, expertise and competence. As reported by Michel et al (2008), the Internet has become one of the widely accessed and primary sources of information on pet nutrition. With the many publicised myths and misconceptions, deciphering fact from fiction can be particularly difficult for owners as well as the veterinary healthcare team. Resources such as those provided by WSAVA (2012) can assist with this process, providing tips on effectively and objectively using the Internet.

While it is important not to judge clients who choose raw feeding as a sole or supplementary part of their pet's diet, it is essential to explore their motivations behind this decision and to do so with care and tact. The nutritional status of an animal can be grossly evaluated through assessment of bodyweight, condition and activity level. However this is no substitute for a full nutritional assessment (including the acquisition of a full dietary and medical history) of every patient at every visit (Baldwin et al, 2010; Freeman et al, 2011). When recording the dietary history, treats, table scraps and food used to administer medications should all be considered. A good quality, balanced diet suitable for the lifestyle, age and species of animal should comprise 90% of the daily caloric intake with no more than 10% consisting of treats or other foodstuff (Hand et al, 2010). Deviations from these guidelines risk the creation of major nutritional imbalances (Chandler, 2014).

Opinions on the appropriateness of various diet options are frequently asked by pet owners. The best advice is that diets should be nutritionally complete, and be capable of meeting the nutritional requirements of each individual animal. Although not a guarantee, diets produced by well-known, reputable companies that have undergone feeding trials by equally reputable organisations may be best assurance that the food is good quality. Nutrient profiles should be checked against global resources including those published by the Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO), European Pet Food Industry Federation (FEDIAF) and National Research Council (2006). Concerns over a diet's suitability can also be addressed by submitting a representative sample of the diet to a reputable laboratory for nutritional assessment (Taylor et al, 2009). The difficulties in correcting an unbalanced diet are well documented (Freeman and Michel, 2001) and often beyond the skills set of many veterinary practitioners (Remillard, 2008) therefore advice should be sought where necessary from a boarded veterinary nutritionist.

In contrast to commercially produced pet food, raw feeding programmes claim to provide dietary micronutrient and macronutrient minimums over weeks rather than at each meal and this necessitates dietary rotation and good owner compliance. Owners must be warned that deviation from the prescribed feeding regimen or use of a recipe not tailored to individual nutritional requirements can lead to malnutrition and associated complications in pets (Rahaman and Yathiraj, 2000; Remillard, 2008). A case report by Verbrugghe et al (2011) clearly demonstrates the importance of pet owner compliance and the return of clinical disease if dietary correction is not maintained. It is essential to clearly communicate to pet owners the reasons behind why a prescribed dietary treatment is necessary and for all household members to recognise, accept and commit to accomplishing the proposed goal. It should be further noted that supplementation is not a guaranteed assurance against nutritional imbalances (Yin, 2007; Laflamme et al, 2008).

In order to address the public health risk from pathogen exposure and prevent zoonosis, food safety practices (i.e. careful cleaning of utensils and work surfaces) should be emphasised together with stringent personal hygiene (e.g. hand washing). To address the bacterial and parasitic risk, Freeman and Michel (2001) recommend cooking the food being offered and treating pets with an effective anthelmintic. Hospital guidelines and policies, such as those published by Tufts University (2015), prohibiting raw feeding in the clinical environment should be highlighted to clients together with an explanation surrounding the reasons why. It is also important to raise awareness of the association between raw feeding and development of fixed-food preferences and the subsequent difficulties in making any food changes (Hand et al, 2010). This can prove problematic for the veterinary healthcare team when feeding hospitalised patients.

Pet owners adamant on feeding a raw diet must be made aware of the associated concerns, controversies and potential health dangers surrounding this feeding strategy. It is also important to warn that nutritionally-related disease can mimic other forms of chronic illness (Weeth, 2013) and subclinical disease is a potential concern for patients fed raw or homemade diets. Freeman and Michel (2001) recommend routine veterinary examination two to three times per year to review nutritional integrity and facilitate early identification of nutritional risk factors. Weeth (2013) further endorses 6 monthly monitoring for animals with chronic disease. Appropriate advice and recommendations should be evidence based wherever possible and a record of the discussion clearly documented on the patient's medical record.

Conclusion

It is clear that the new landscape of feeding practices includes a segment of pet owners that are committed to feeding raw meat-based diets. The reasons for choosing this approach of feeding range from the belief that it is more natural and appropriate for animals to simply a distrust of manufactured pet foods. It is also apparent that many of the arguments used to support raw meat-based diets are not based on fact and involve misconceptions and misinformation. Even when misinformation is clarified, some owners still opt to feed raw meat-based diets. It is therefore important to educate pet owners about the risks involved both to the pet and also to themselves and their family. Nutritional inadequacies, excesses and bacterial contamination are the most serious potential consequences that must be clearly explained to pet owners. Ongoing research on the impact and risks of feeding these diets to companion animals should enable veterinarians and VNs to better inform clients about their options and ways to reduce risk of illnesses related to this type of feeding.