References

Clinical presentation and management of liver lobe torsions in domestic rabbits

Abstract

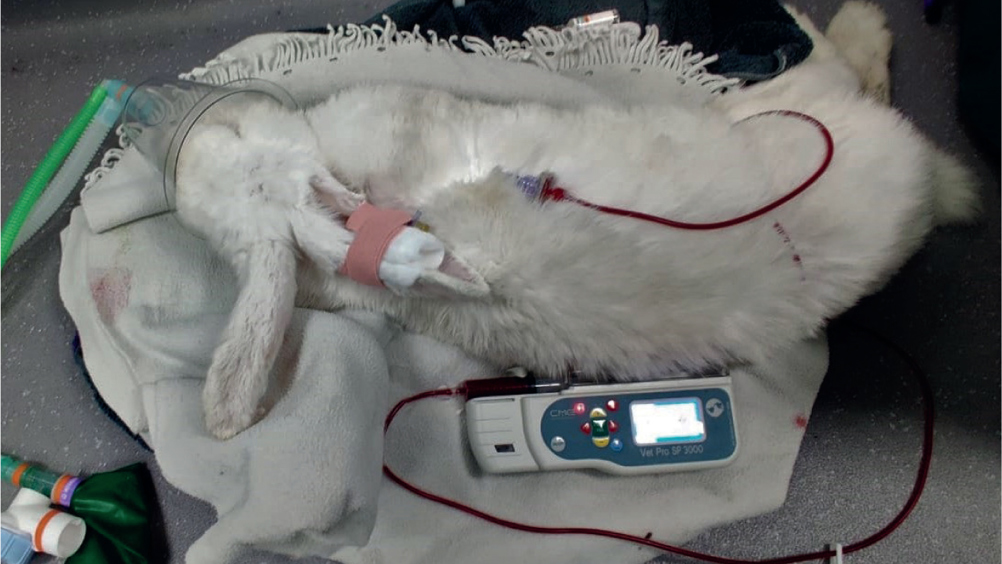

Rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) are common household pets, and make endearing companions for both the young and old. Rabbit medicine has advanced greatly in recent years, and we are now able to recognise, diagnose and treat many conditions and presentations that may have previously been poorly understood. One of the conditions that is increasingly recognised is liver lobe torsion, which can prove difficult to recognise in clinical practice, especially if the team has not encountered the condition before. The purpose of this article is to highlight liver lobe torsions in rabbits, their presentation and treatment options and nursing care, and describe a successful case seen at the clinic.

A liver lobe torsion is when one or more of the liver lobes twist, with some reports documenting this including the gall bladder (Massari et al, 2012). Liver lobe torsions are documented in a variety of species including dogs (Schwartz et al, 2006), humans (Umehara et al, 2009), cats (Nazarali et al, 2014), horses (Bentz et al, 2009), guinea pig (Waugh et al, 2021), otters (Warns-Petit, 2001), camels (Ibrahim et al, 2021), ferrets (Vilalta et al, 2016) and rabbits among others.

The condition of liver lobe torsion is considered rare in rabbits, but the author believes that the condition is likely to be underdiagnosed, especially in this species because of the difficultly in recognising clinical signs. A study in 984 laboratory rabbits showed that 0.3% of asymptomatic rabbits had suffered from a liver lobe torsion (Weisbroth, 1975), highlighting that these can be subclinical. A rabbit's liver comprises four lobes, the caudate lobe and three cranial lobes called the right, medial left and lateral left lobes. The most commonly affected lobe is the caudate lobe, accounting for 62.5% of liver torsions documented at one clinic (Graham et al, 2014), however, torsion of other lobes is documented (Graham and Basseches, 2014). The reason for the torsion is not fully understood, but in dogs suggested causes include large breed predisposition, previous gastric dilatation and volvulus, neoplastic changes, trauma and vigorous jumping (Bhandal, 2008). Predisposing factors are not fully described in rabbits, however, theories include the absence of hepatic supporting ligaments, trauma, episodes of gastrointestinal stasis resulting in gastric dilatation and stretching of the left triangular ligament, and bacterial or parasitic hepatitis (Summa and Brandão, 2017).

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting The Veterinary Nurse and reading some of our peer-reviewed content for veterinary professionals. To continue reading this article, please register today.