Planning patient care is an integral part of veterinary nursing practice. Part one of this article introduced how the Orpet and Jefery Ability Model (OJAM) (2007) can be used to facilitate a nursing-focussed approach to this planning and care, encouraging veterinary nurses (VNs) to take a holistic view of their patients. During this second part, the themes arising from using this particular framework will be examined, followed by a conclusion of recommendations for future practice.

Aims

While published reflections on the design and implementation of care plans based on the OJAM (2007) almost uniformly identify the advantages of utilising this framework for planning patient care, they have all also raised common difficulties in integrating such an approach within veterinary practice (Lock, 2011; Wager, 2011; Brown, 2012). The aim of this article is to explore these outcomes further by utilising the experiences of 56 registered VNs (RVNs) in practice during their implementation of a framework for planning patient care as part of a learning activity in a continuing education course. It is proposed that by doing so it may be possible to further establish the positive effects of utilising the OJAM (2007) and to discover what solutions, if any, have been found to the challenge of incorporating the use of this model into the demands of daily life in veterinary practice.

Methodology

During the module of the Royal Veterinary College (RVC) Graduate Diploma in Professional and Clinical Veterinary Nursing (GDPCVN) titled Applied Clinical Nursing, students, all of whom were RVNs, were asked to use a framework such as the OJAM (2007) to plan a patient's care within their practice and then reflect on this experience. A thematic analysis of the discussion forum posts of three student intakes, comprising 56 RVNs in total, on this module was performed. This examination of how students approached the task of implementing a framework for planning care and the subsequent outcomes of doing so, revealed the following themes.

Emotional response to implementing the documented planning of patient care in practice

Despite all of the GDPCVN students being RVNs with at least 1 year's post-qualification clinical experience, the emotional response to the task of implementing the documented planning of patient care in their practice was striking, with the following words frequently recorded:

To the knowledge of the authors, attitudes such as these in response to utilising a care plan framework in veterinary practice have not previously been documented. It is acknowledged however, that any change to practice can be stressful, as it creates an overall sense of uncertainty, which subsequently results in worry (Hibbert, 2011).

Girotti (2011) and Hibbert (2011) also document other themes regarding reactions to change in veterinary practice, which may be applicable here. It is suggested that another element of resistance to change is that it often represents the unfamiliar; as familiar practice represents security, there may be a fear of insecurity when altering the way things are normally done (Girotti, 2011). If this is the case in relation to the emotional responses detailed above, it raises the question, why should there be such unease regarding care plans, when it would be possible to assume that their use in practice should be routine, due to the fact that they have been an integral part of the VN qualification since 2006? The authors propose that this unease may be evidence of the assertion made in part one of this article, which is that while the concepts of models and care plans continue to be advocated by veterinary nursing academics (Orpet and Jeffery, 2006; Orpet and Welsh, 2011), their existing uptake and use in clinical practice is actually minimal.

However, the question of what is the root cause of this apparent lack of use of care plans by practising RVNs in the clinical setting remains. One possible answer is that the concepts, theories and models primarily taught to student VNs during their training are those imported from the human nursing professions, namely the Roper, Logan and Tierney Activities of Living Model and Orem's Self-Care Deficit Model (Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, 2011). In the authors' experiences, both student and qualified VNs alike find the application of these human-based models to veterinary patients challenging and often the experience of attempting to use such non-veterinary-specific concepts can be sufficient to discourage VNs further investigating the possible use of care plans thereafter. One GD-PCVN student wrote:

‘These [Orem and RLT] were used in our VN training and I found them very difficult to use and did not really understand them. I am ashamed to say [I] tried to shy away from them [care plans] since.’

Further support of these assertions can perhaps be drawn from the fact that, to the authors' knowledge, there is no published evidence to suggest that Orem's Self-Care Deficit Model in particular has ever been utilised within clinical veterinary practice. Even within the academic literature it is acknowledged that VNs are generally sceptical of this model's applicability and usefulness to their practice (Davis, 2007).

Utilising the Orpet and Jeffery Ability Model (2007)

Perhaps serving as further evidence to support the assertions made in the preceding section, the OJAM (2007), as described in part one of this article, was consistently selected by the GDPCVN students for use over other available care plan frameworks; 94% of the GDPCVN students selected the OJAM (2007) to help design and implement their care plan. The most frequent reason cited for this was that it was the framework these students felt that they could most ‘relate to’ in terms of their own nursing practice because it is veterinary specific. This is consistent with the reflections of existing published accounts of the use of care planning in practice (Lock, 2011; Wager, 2011; Brown, 2012).

As a result of this overwhelming use of the OJAM (2007) by the GDPCVN students, please note that all of the subsequent identified themes relate solely to the use, and in some cases modification, of this particular model.

Recognition and enhancement of the unique role of the veterinary nurse

A recurring theme during the GDPCVN students' reflections having been asked to design and implement a care plan was the positive effect it had on the GDPCVN students' perceptions of their role as VNs:

It would therefore appear that use of the OJAM (2007) did, as proposed in part one of this article, facilitate the adoption of a more ‘veterinary nursing approach’ to the VNs' work. This approach can perhaps be characterised as one where the VN instigates and takes responsibility and ownership of his or her own veterinary nursing practice, rather than following the instructions and orders of the veterinary surgeon (VS) alone, in what has sometimes been referred to as the ‘hand-maiden’ role (Pullen, 2006; Brown, 2012).

The possible implications of such a shift in practice are potentially very powerful. In the reflections of the GDPCVN students, the viewpoints as detailed above seem to be inextricably linked to increased feelings of pride and job satisfaction. As highlighted by Lock (2011), a high level of job satisfaction stemming from a greater utilisation of the nursing skills of VNs in practice can have far reaching effects, including improved retention of VNs to the profession and increased client satisfaction. This analysis of the GDPCVN students' experiences can therefore serve to also support Lock's (2011) assertions that care planning can provide a medium to achieve all of these things.

Improved individualised and patient-specific care through use of the client questionnaire

As demonstrated by Tzeng et al (2002), there can be a link between increased job satisfaction and improved patient results. In the experiences of the GDPCVN students this would appear to be the case; in parallel to the positive outcomes being experienced by the RVNs were observations of how they perceived that use of the OJAM (2007) had positively impacted on patient care:

These, and numerous other similar comments, all draw attention to how the use of the OJAM (2007) to plan the nursing of patients has the potential to result in improved care, in particular through the increased understanding of the individual needs of the patient. This supports existing case studies in the veterinary literature, where nursing guided by a model of care has yielded similar outcomes (Joiner, 2000; Davis, 2006; Wager, 2011; Brown, 2012).

Interestingly, this increased understanding of an individual patient's needs was generally attributed to the extensive initial patient assessment, generally in the form of a client questionnaire, which as illustrated in part one of this article, is an integral part of the OJAM (2007):

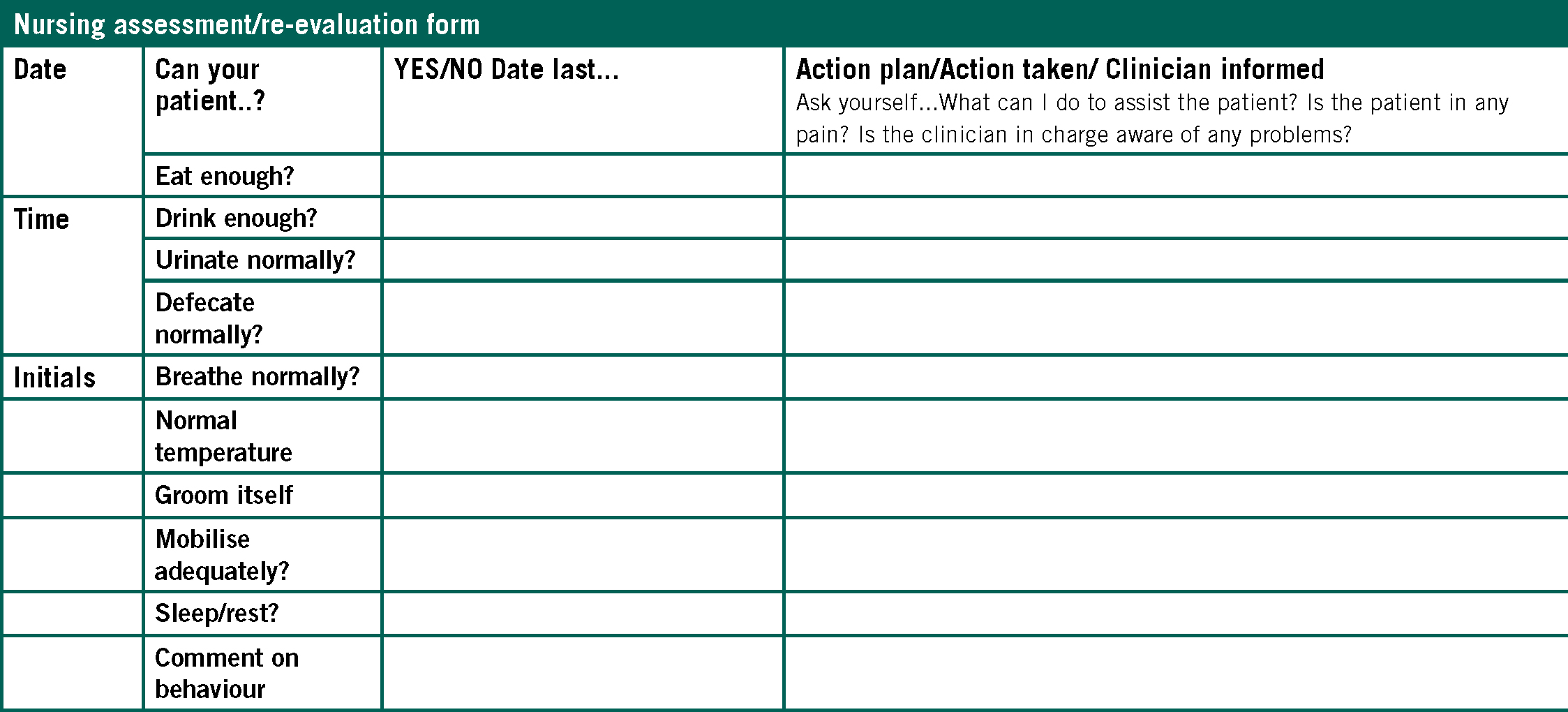

This analysis of GDPCVN student experiences must therefore help to endorse the use of the OJAM (2007) with its significant focus on a nursing assessment of the patient taking place at admission. This supports the points made in the veterinary literature that comprehensive data collection is essential prior to planning patient care and that it is chiefly the nursing assessment interview process of the OJAM (2007) which greatly enhances the holistic care provided to patients (Davis, 2007; Lock, 2011).

Length of time taken to complete the planning of patient care

Despite all of the universally positive outcomes explored so far, it must be acknowledged that perhaps the most frequent observation of all made by the GDPCVN students is that planning patient care is time consuming. This led many of them to conclude that the use of care plan documentation is impractical for practice, with an additional risk being that they may neglect patient care in order to complete the paperwork. Some attributed this to the repetitive format of the documentation they selected to use. Such observations are by no means surprising, given that each of the reflections on the use of the OJAM (2007) by RVNs in practice to date all recognise these same issues (Lock, 2011; Wager, 2011; Brown, 2012).

The time consuming nature of documenting the planning of patient care in practice has to be a significant concern for the profession, if as suggested by Lock (2011) and supported here, it simply makes the process unfeasible for routine use in clinical practice. The overwhelming benefits of the OJAM (2007) as established throughout this article cannot be of any consequence to veterinary nursing if the application of the model cannot be modified in such a way that it can actually be used by practicing VNs; otherwise it is doomed to be rather like a prescription diet which is of no use if the patient will not eat it.

What then is the solution to this problem? One possible answer is that this issue could be a diminishing one if the OJAM (2007) was routinely adopted by practicing VNs. Several of the GDPCVN students support the assertions of Brown (2012), by reflecting that if they were to use this approach to their nursing practice regularly, they would become more efficient. One GDPCVN student said:

‘With each plan I will learn more and improve in speed and also develop a quicker train of thought in relation to the nursing care needed.’

This viewpoint is supported by Benner's (1982) application of the Dreyfus model of skill acquisition to human nursing, which have become known as the stages of clinical competence. Benner (1982) recognises that a nurse's speed and mastery of nursing tasks increases as their experience progresses them from novice to expert.

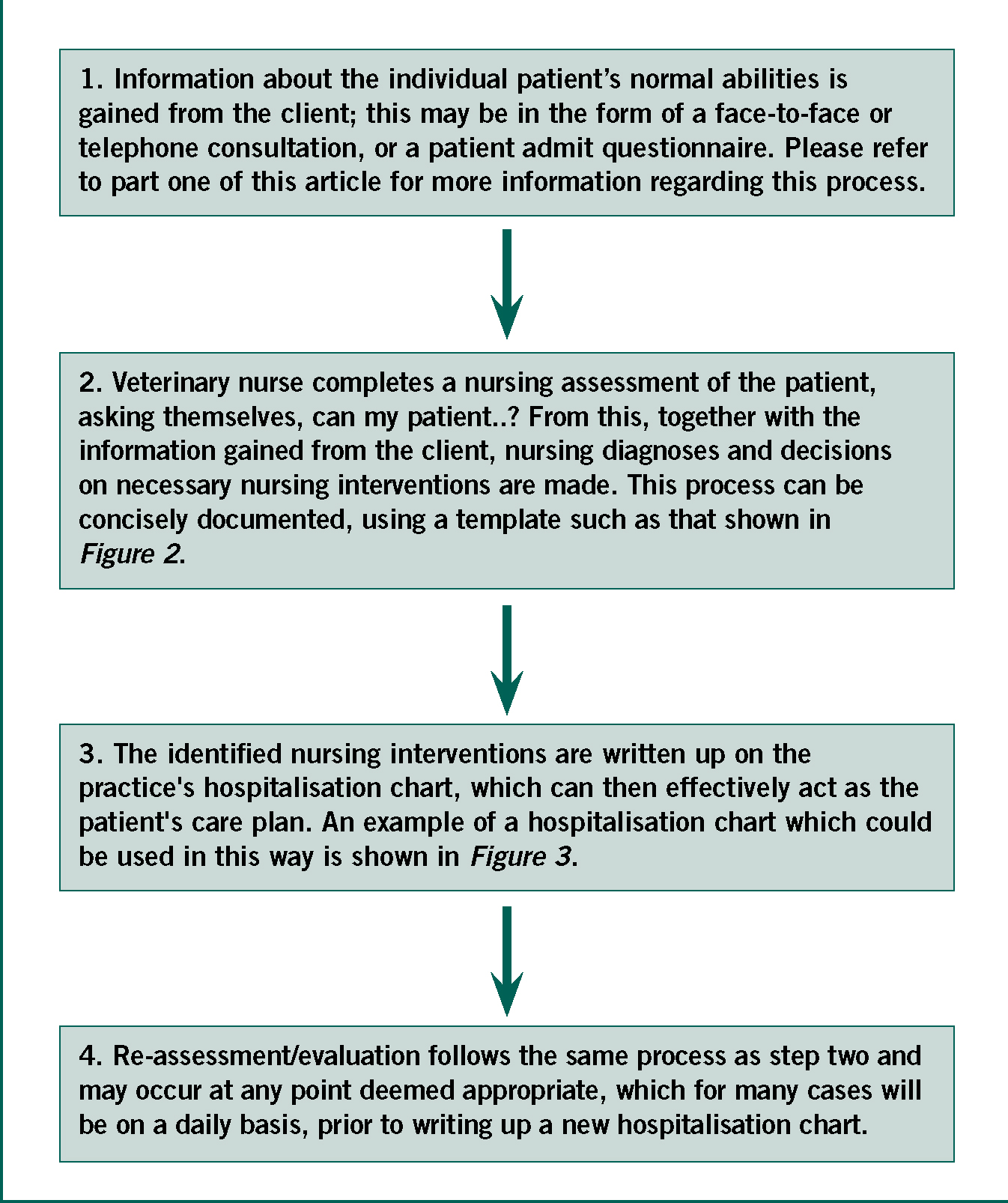

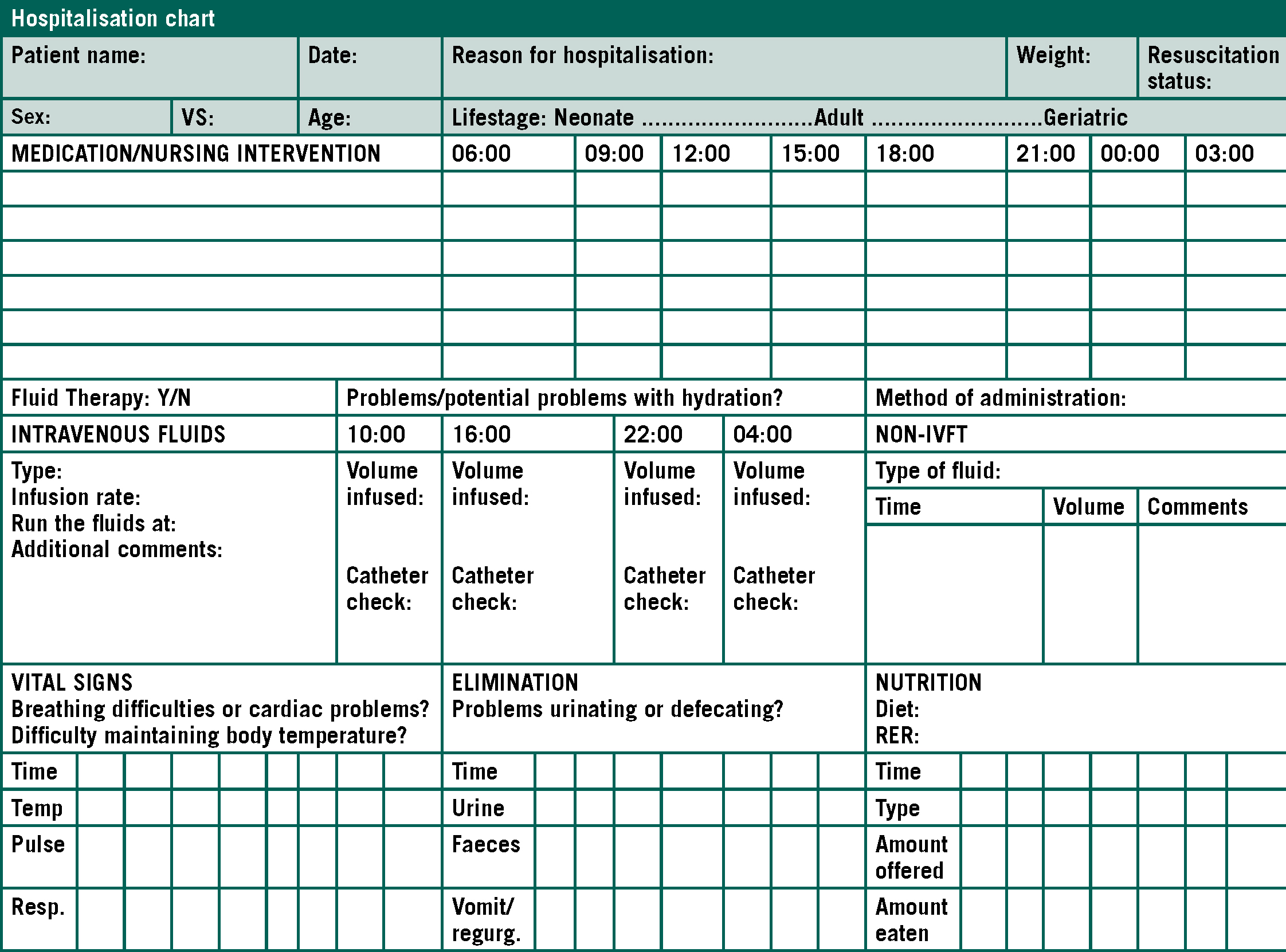

The other aspect of reducing the quantity of paperwork and thus time traditionally associated with documenting the planning of patient care is to devise innovative local adaptations of the proposed templates of the OJAM (2007), as outlined by Wager (2012). While the need for such adaptations is acknowledged by Orpet (2008) and encouraged by Davis (2007), veterinary nursing literature to date has yet to provide VNs with many specific examples of how this might be achieved. Inspired by the work of Orpet (2011) and innovations developed by GDPCVN students in response to this challenge, the authors therefore propose a suggested process for integrating the use of the OJAM (2007) into clinical practice. This is shown in Figures 1 to 3.

Conclusions and recommendations for future practice and further research

The aim of this article has been to explore the experiences of RVNs in practice during their implementation of a framework for planning patient care in order to build on the existing literature (Joiner, 2000; Davis, 2006; Lock, 2011; Wager, 2011; Brown, 2012) and thus enable a greater level of clinical expertise in this area of veterinary nursing to be shared. Through doing so, it has been possible to show that, in the case of the GDPCVN students, use of the OJAM (2007) is preferred over human nursing models and that use of this veterinary nursing model has the potential to positively enhance both the veterinary nursing role and improve patient care. A significant contributing factor of the latter is the attention paid by the model to the importance of nursing assessment.

Despite this, it has also been concluded that among the GDPCVN students, there appears to be an initial general level of unease regarding the use of care planning in clinical practice. While various reasons for these feelings have been discussed, if they can be attributed to initial encounters with human nursing models during training, then it may be time to consider the helpfulness of such models remaining as part of the VN training landscape. This subject may be of interest for further qualitative study, as would a quantitative assessment of how many veterinary practices are actually utilising care plans, and if so in what format and with what outcomes.

Finally, it is asserted by the authors that it is a priority for the profession to embrace the use of a veterinary specific framework to planning patient care in practice in order to change the way we think about and nurse our patients for the better, by identifying and developing a unique and patient-focussed approach, while also encouraging evidence-based nursing interventions. Part of this embrace needs to be the adoption of the OJAM (2007) into VN training and subsequently practice, which itself has a growing evidence-base supporting its use. In order to achieve this, VNs need to call on their inherent ingenuity and resourcefulness in order to devise the local modifications which will mean that documenting the planning of patient care becomes a feasible and practical reality in clinical practice, something which it has been shown here can only serve to benefit patients, VNs and practices alike.