Veterinary nursing in the UK is taking some of the first crucial steps towards professionalization with the recent introduction of registration of members, impending disciplinary procedures and amendments to the law which specifically refer to the work of veterinary nurses. Each of these developments is significant and each is an essential component in the evolution towards professional status, but there are several other crucial elements that veterinary nurses need to implement before they can secure this status (Branscombe, 2010;Clarke, 2010;Banks, 2010/11). One well-documented condition is that a profession has its own unique body of knowledge and evidence base on which to base its clinical and professional practice (Hern, 2000;Mahony, 2003;Holmes and Cockcroft, 2004;Pullen, 2006).

Peer-reviewed journals such as The Veterinary Nurse provide a hugely significant advancement for veterinary nursing's endeavour towards professional recognition. Published case reports can assist veterinary nursing practitioners to gain a deeper knowledge and understanding of their clinical veterinary nursing practice, share and foster good practice and start to build an evidence base on the care that should be provided to patients (Dias, 2010; Jamjoom et al, 2010). There is an undercurrent of negative attitude held by some medical journals that case reports do not provide a robust source of evidence base compared with primary research studies, but there are those that argue that despite their anecdotal nature, case reports still play a hugely important part in the development of a profession, and provide a noteworthy method of sharing knowledge and generating an evidence base (White, 2004; Jamjoom et al, 2010). The authors of this article believe that at this stage in the journey toward professionalization, publishing case reports provides a powerful way of creating a knowledge base and will help define the role of the veterinary nurse in particular in relation to patient care. Case reports have the potential to provide a number of different groups within any profession tangible benefits; for student veterinary nurses such reports can help develop students' knowledge and understanding about specific conditions (Jamjoom et al, 2010) and provide them with opportunity to develop skills in academic and scientific writing. For practitioners they provide a means of creating a record of clinical practice and to convey unusual or challenging patient presentations to their colleagues (White, 2004). When published in journals, such as this, they help others in the profession develop specialist knowledge and highlight issues which can then be further explored through research studies (Cohen, 2006).

Traditionally, patient care reports are called ‘case’ reports by the majority of other professions, including the veterinary and paramedical professions. The authors of this article suggest that veterinary nurses, in their endeavour to move towards a more holistic and patient-focussed approach to the delivery of their nursing care, should steer clear of using the term ‘case’ which identifies patients by their condition rather than recognizing them as sentient beings with specific requirements of their own (which may or may not be related to the disease or disorder they present with). Referring to a patient as ‘the GSD with the fracture’ could be considered to foster a medical approach (Orpet and Welsh, 2011) and it is becoming more widely recognized in veterinary nursing that the medical model is an out dated and inappropriate way to approach patient care (Jeffery, 2006; Pullen, 2006). If the terminology used by the profession contributes in part to the way we provide care for our patients, then the authors recommend that the vocabulary we adopt fosters a more patient-focussed approach. As a simple example, a typical title for a case report might be ‘Case report of diabetes insipidus’, whereas a more patient-focussed approach would be to use a title such as ‘Patient care report of the nursing care provided to feline patient with diabetes insipidus’. Therefore, it is suggested that the terminology patient care report (PCR) would be a more appropriate way to refer to these types of report.

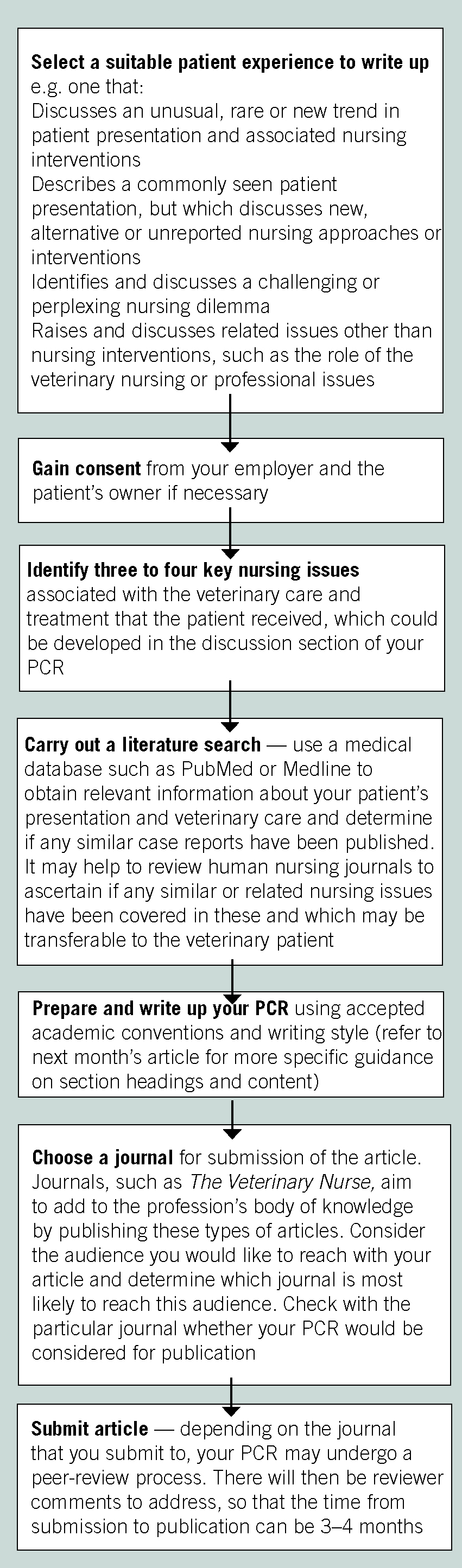

For those new to writing for this type of publication, the task of preparing this type of report can be daunting and time consuming. As Budgell (2008) points out, these types of reports should ideally written by those working in clinical practice, but too often clinical practitioners have little experience or confidence in writing for academic journals and struggle to find the time to write up their experiences in a format suitable for peer-reviewed journals (White, 2004). The aim of these guidelines is to help all veterinary nurses, and particularly those working at the front line of veterinary nursing practice, master some of the conventions of academic writing and become more efficient at writing high quality and reliable reports to a publishable standard. It should be noted that these are guidance notes, intended to help the novice writer achieve a document of a certain academic standard. They should not be considered the definitive word on writing PCRs and any veterinary nurses considering writing up such reports should check first with the publisher for any specific requirements (Figure 1).

What are PCRs?

PCRs provide a written account of a practitioner's observations and experiences while nursing a particular patient. These reports should not only identify the patient's presenting problems and description of what was done, but also show how the author has integrated and applied theory and an evidence base into the nursing care provided for the patient while under their care. Crucially, PCRs should demonstrate that the author has critically evaluated the nursing intervention that took place and provide some recommendations for future practice. When authors provide not only a written description of what happened, but also provide a critical evaluation of the nursing care provided to a particular patient (by jusification and discussion of alternatives to the care provided using an appropriate evidence base), PCRs have the potential to enable veterinary nurses to gain fresh and improved insight into clinical practice. This could be described as a way of undertaking reflective practice. As advocated by Schön (1987) and many others since, reflection of one's personal and professional practice helps develop one's own, and also the audience's knowledge and understanding of clinical and professional practice. Burns and Bulman (2000) advocate, reflection is a way to stimulate a more critical approach to clinical practice and McBrien (2007) suggests that reflection on daily activities can be self empowering and help members of a profession gain control over some of the issues and complexities of their day-to-day work.

Which patients should PCRs be written about?

Those new to writing PCRs report that they find it difficult to know which patient experiences warrant writing up for publication. PCRs should reflect aspects of the VNs clinical work which were either entirely managed by them or in which they had significant involvement. The authors recommend that those new to writing this type of report should select a patient experience which is sufficiently complex to allow adequate analysis, but not one with multiple problems or that is so overly complex that it becomes too difficult to write a well-structured, reflective review within any word limit imposed by the publisher. The most informative PCRs are not necessarily about the most unusual or complex patients. Sharing good practice about the care of patients seen every day will stimulate further discussion and hopefully start to create an evidence base for patient care.

What should the focus of a PCR be?

The focus of a PCR should be based around how the patient was managed and provide a critical evaluation of the nursing intervention carried out. It may be appropriate to focus the report on one particular nursing domain, for example, a surgical PCR should primarily centre on the nursing considerations of the patient related to the pre-, peri- and post-surgical period rather than digressing into any considerations relating to the anaesthesia. PCRs should not be a lengthy description of the diagnosis and/or treatments given by the veterinary surgeon but should instead focus on discussion of the nursing interventions taken and the care provided. Discussion and reflection of some of the complex problems faced while nursing the patient should be provided with exploration of alternative approaches to nursing care that might have been taken.

What academic style and presentation is expected?

Published PCRs should follow accepted academic conventions using suitable language and vocabulary. PCRs should be written in the third person, in past tense. The structure of the report should be coherent, logical and organized, using headings and subheadings to break the report up into appropriate sections (see next month's follow-up article). As with any published material, the content should be entirely the author's own work to avoid plagiarism, and statements, opinions and the ideas and work of others should be referenced appropriately. Work should be spell and grammar-checked (UK English). Proof reading is essential as word processing programs do not always pick up spelling or grammatical errors. Individual journals will specify the minimum and maximum number of words permitted.

Are there conventions that need to be adhered to?

There are certain conventions which are particular to writing any medical/veterinary case reports and these should be followed:

Photographs, radiographs, illustrations and tables may be included in PCRs. If they are clear and accompanied by a legend they can be an excellent addition. However, the anonymity of any clients, colleagues or patients must be maintained (i.e. do not include any information or identifiable features) unless consent has been obtained to use the images.

Authors are also advised to obtain permission from their employers and/or the supervizing veterinary surgeon before submitting a PCR for publication.

Conclusion

PCRs have the potential to make a significant contribution to the development of a patient care evidence base so desperately needed by veterinary nurses today in their journey toward professional status. PCRs should ideally be written by those working in clinical practice as a way to share and develop best practice in patient care. However, many veterinary nurse practitioners are unfamiliar or inexperienced with writing this type of report for publication and are unclear of some of the formalities of academic writing. This article is the first of a two-part series and provides readers with an overview of some of the reported benefits of writing and publishing these types of reports particularly for any vocation progressing toward professionalization. Potential authors are also provided with some guidelines on the content and language style that these reports should contain.

In the next edition, part two of this series will provide readers with more practical guidelines and instruction to help them record and critically reflect on their experiences of patient care to help them create PCRs suitable for publication.