The patient presented with a 2-day history of vomiting, anorexia and lethargy. On admission, she was trembling and panting. There was a previous history of a gastrointestinal foreign body.

Signalment

Species: Canine

Breed: Labrador crossbreed

Age: 11 years 11 months

Sex: Female neutered

Weight: 23.6 kg

Patient assessment

On physical examination, the patient was quiet and lethargic but responsive. Her mucus membranes were pink and moist and capillary refill time was two seconds. The patient was tachycardic and panting. Her temperature was 38.9°C and she experienced pain on abdominal palpation.

Veterinary investigations

The veterinary surgeon requested a comprehensive blood profile including electrolytes, haematology, biochemistry and a canine pancreatic lipase (cPLI) test. The cPLI was abnormal, her urea was 11.9 nmol (1.70–7.40 nmol), alkaline phosphatase (ALKP) was 580 nmol (12–83 nmol) and phosphate was 2.50 nmol (0.80–1.80 nmol). The veterinary surgeon diagnosed acute pancreatitis, but the presence of a gastrointestinal foreign body could not be ruled out. Supportive treatment, including intravenous (IV) fluid therapy, analgesia, antacids and antiemetics, was initiated.

Two hours following admission, the patient's condition deteriorated; an ultrasound and radiograph were carried out. At this stage, the patient was believed to be in the early stages of septic shock resulting from septic peritonitis.

Discussion of nursing interventions

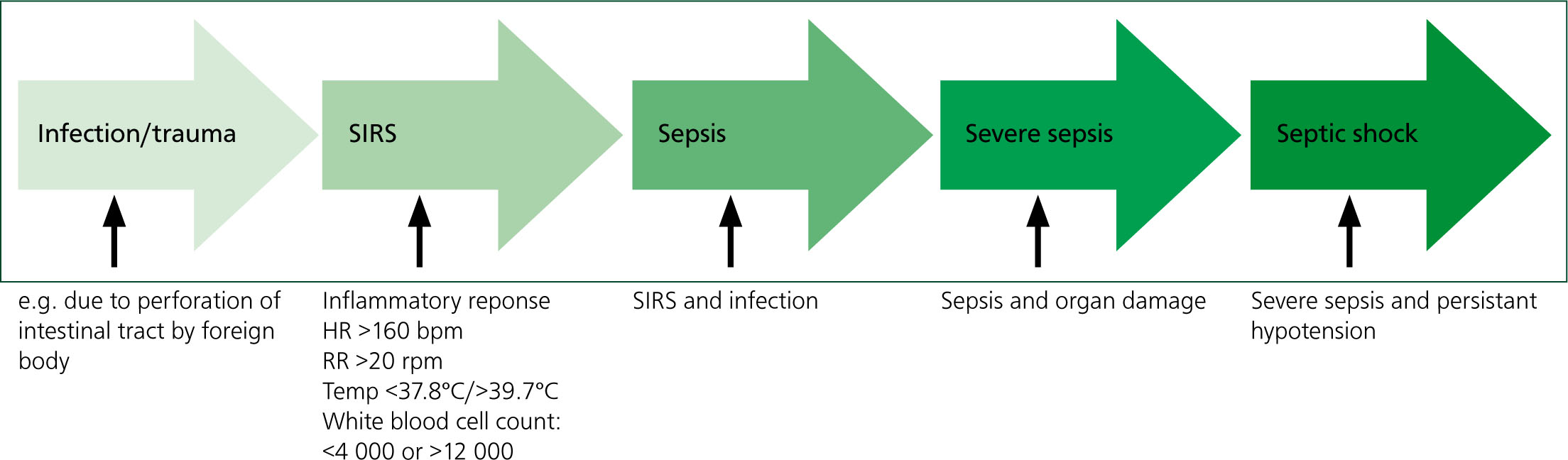

Sepsis is an inflammatory condition resulting from bacterial contamination, and is commonly observed following perforation of the gastrointestinal tract by a foreign body (Swayne et al, 2012). Sepsis is potentially fatal; if left undiagnosed, secondary multi-organ dysfunction is likely to occur, resulting in death (Bentley et al, 2007).

When the body identifies an infection, a controlled inflammatory response is established to eliminate the invading pathogen (Breton, 2012). The inflammatory cascade is a mediator-driven system. It begins when immune cells are activated as a result of cell injury to produce cytokines, which act as mediators in the inflammatory cascade. These mediators can be classified as pro or anti inflammatory, and they have different effects at different stages (Aldrich, 2007). Cytokines are produced by macrophages and are activated in response to cell injury. Tumour necrosis factor and interleukin 1 are the main pro-inflammatory cytokines. When these are released into the body, clinical signs such as anorexia, hypotension, pyrexia and tachycardia can be seen (Aldrich, 2009). This is termed the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) (Mittleman Boller and Otto, 2009) (Figure 1).

In 1997, Hauptman et al conducted a study to establish the specific parameters indicative of canine SIRS. They concluded that, when a patient has two or more of the following clinical signs, SIRS can be confirmed: a heart rate over 160 beats per minute; a respiration rate above 20 respirations per minute; a body temperature of less than 37.8°C or more than 39.7°C; and a white blood cell count of less than 4 000 or more than 12 000. Using these parameters, it can be concluded that the patient in this study was positive for a SIRS.

Multiple elements must be considered when nursing a patient in septic shock. These include: administering antibiotic and analgesic regimens based on vital signs monitoring and pain assessments; implementing advanced monitoring including blood testing; and blood pressure monitoring to ensure adequate fluid therapy. Finally, behavioural changes, the ability to urinate and defecate, and comfort for recumbent patients should be considered (Lanz et al 2001; Crompton and Hill, 2011; Breton, 2012).

The patient was nursed intensively before surgery and this study focuses on fluid therapy, pain assessments and basic monitoring.

Basic monitoring

In 2012, Breton stated that septic patients should be assessed every 4–6 hours, and this should include evaluations of heart rate, respiration rate and effort, temperature, mucous membrane colour, capillary refill time and behavioural changes.

The patient was monitored every 30 minutes for the first 3 hours and hourly thereafter. She began to deteriorate, showing early signs of septic shock — tachycardia, increased systemic blood pressure, brick red mucous membranes and fever. The later stages of sepsis lead to tachypnea, severe hypotension, depression and multi-organ dysfunction. Therefore, the author recommends that basic vital signs should be monitored every 15–30 minutes in unstable septic patients.

Breton (2012) identified that blood glucose monitoring is important in septic patients, considering that hypoglycaemia is a concern because of anorexia. Breton (2012) further stated that, although once daily monitoring is acceptable, more frequent monitoring is recommended should hypoglycaemia be suspected. In this case, doing this was not considered; further monitoring of glucose levels could have provided the veterinary surgeon with valuable information and led to the administration of IV dextrose which may have proved beneficial to the patient.

Septic patients can quickly progress to shock, and blood pressure (BP) monitoring can be used to identify hypoperfusion and hypotension. The patient was hypertensive, which is unexpected in shocked patients; changes in BP are detected by baroreceptors and hypertension leads to compensatory peripheral vasodilation (Boag and Hughes, 2005). Other factors, particularly pain, can lead to a high BP (Pachtinger, 2013). Since compensated shock may produce parameters that are not noticeably abnormal, BP monitoring must be carried out frequently to detect the decompensated stages (Porter et al, 2013). The patient's BP was monitored once; in hindsight, she could have benefited from further readings.

BP monitoring can be implemented using indirect methods including using a Doppler flow monitor (Figure 2) or an oscillometric device (Figure 3), or direct techniques using arterial blood pressure measurements (Bosiack et al, 2010). A Doppler flow monitor was used to monitor this patient's BP; direct techniques are seen as gold standard for care since they allow trends in pressure changes to be closely monitored (Pachtinger, 2013). Most patients, however, will not tolerate catheter placement unless anaesthetised or critical so catheters are unsuitable for most conscious patients (Clapham, 2011).

The detection of the pulse in the Doppler method can be subjective and therefore open to inconsistences so must be interpreted alongside other parameters measured (Clapham, 2011). Bosiack et al (2010) compared indirect and direct BP monitoring techniques in 11 dogs. Although only a small sample group was used, they concluded that the indirect methods did not meet the validation standards set out in human medicine, and that direct techniques were more accurate. They suggested that inconsistencies in indirect techniques were due to incorrect cuff selection and patient preparation. Practices should ensure nurses are adequately trained in using indirect techniques given their common use in first opinion practice (Clapham, 2011).

The patient's temperature was closely monitored throughout her stay. On admittance, her temperature was 39.9°C. This increased to 41°C, at which point a fan was used to reduce her temperature. A high temperature can cause tachycardia, tachypnea, panting and tacky, red mucus membranes (Mann, 2012). Pachtinger (2013) identified the importance of dfferentiating between hyperthermia and fever. Hyperthermia is seen following exogenous causes such as a rise in environmental temperature, and an increase in muscle activity, for example during exercise. Fever occurs following endogenous causes such as infection, inflammation or neoplastic processes.

Therefore, patients presenting with hyperthermia require active cooling measures when temperatures exceed 40°C. Those with fever, however, should not be cooled and the underlying cause should be treated. Cooling a patient with fever can lead to vasoconstriction, which can reduce heat loss (Mann, 2012). Using a fan on this pyrexic patient may have prevented appropriate heat loss and, in hindsight, should not have been used. Following analgesia, antibiotics and fluid therapy, her temperature started to decrease.

Pain assessment

Pain assessment in a patient with sepsis should be carefully considered, as correct regimens to treat it can help reduce the likelihood of morbidity and mortality (Murphy and Warman, 2007). Opioids are an appropriate choice in treating acute abdominal pain.

The patient was given two injections of methadone at a dose of 0.3 mg/kg 3 hours apart, but remained in pain. Multimodal analgesia seems to be the most effective method of treating chronic pain, but studies in acute pain are limited (Flaherty, 2013). Abdominal pain is activated by a stimulus such as penetration by a foreign body or an organ stretching. Free nerve endings called nociceptors are activated and an electrical signal is transmitted to afferent nerve fibres via an action potential. A and C nerve fibres exist to transmit the stimuli to the spinal cord, then to the brain (Mazzaferro, 2003). A fibres transmit fast, immediate pain and C fibres transmit slow pain in the form of a dull ache (Bloor, 2012). Since the pathophysiology of abdominal pain is complex, it could be argued that multimodal analgesia has its place in management of acute pain (Flaherty, 2013). Bloor (2012) stated that pain management should be classified as the fourth vital sign, since its effects on a patient's stress levels and recovery can be dramatic.

Pain assessment can be difficult, since response to painful stimuli can vary between individuals. Therefore, a holistic approach should be adopted, including detailed hospital forms, care plans and pain scoring charts. As pain can have detrimental effects on wellbeing, it is imperative that veterinary nurses can assess and identify changes in a patient's ability to eat, sleep, drink and express normal behaviour (Bloor, 2012). A care plan (Table 1) and a hospital chart, covering specific requirements and vital signs, were used when this patient was being nursed. These allowed pain to be identified and a second analgesic dose administered.

Table 1. Nursing care plan

| Patient's name …………………………………………. Date……………………………….…Age: 4 years Time: 9:30am VS: VN: ID No:To be completed once daily or more often following dramatic changes in patient's health or following surgery | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABILITY | Normal routine | Grade | Problem list | NURSING INTERVENTIONS (detail on hospital form with times) | Review time/frequency | Evaluation |

| Eat | Normally eats x2 daily dry food – Chappie from a metal bowl | 3 | Anorexic | Nil per os as potentially having surgery; check with VS hourly to see if situation changes | Hourly checks starting at 12:00 | 12:00 – still nil per os1:00 – still nil per os2:00 – nil per os3:00 – nil per os4:00 – nil per os5:00 – nil per os |

| Drink | Normally drinks from ceramic bowl frequently throughout the day | 3 | Adipsic Dehydrated Vomiting | Place on IV fluid therapy x2 maintenance (Hartmann's, 500 ml bag), following blood results on x2 maintenance, monitor fluids are running hourly to ensure line patent. Carry out hourly temperature, pulse and respiration observations (TPRs) and write on hospital form. Check for any concerns e.g. swelling to foot/leg | Hourly checks | 1:00 – placed on fluids, running well. No abnormalities detected (NAD)2:00 Fluids running well – turned up to x3 maintenance following patient deterioration3:00 – fluids still on x3 maintenance4:00 – running well now on x25:00 – running well on x2 maintenance |

| Urinate | Taken for two walks a day but has access to the garden all afternoon/evening | 1 | Lethargic | Depressed and lethargic — reluctant to go outside. Ensure kennel is kept clean and tidy at all times, place incontinence pad to prevent urine/faecal scalds. Also patient on fluids, so ensure she isn't urinating on herself | Hourly checks for cleanliness | 12:00 – taken outside, urinated1:00 – no urine2:00 – no urine3:00 – no urine4:00 – no urine5:00 – no urine |

| Defecate | Taken for two walks a day but has access to the garden all afternoon/evening | 3 | Diahorrea, lethargic | Depressed and lethargic — reluctant to go outside. Ensure kennel is kept clean and tidy at all times, place incontinence pad to prevent urine/faecal scalds | Hourly checks | 12:00 – taken outside, no faeces1:00 – no faeces2:00 – no faeces3:00 – no faeces4:00 – no faeces5:00 – no faeces |

| Breathe | No usual problems | 2 | Panting | Monitor hourly vitals and record on hospital form. Inform the VS if increasing above normal ranges or decreasing below normal ranges | Hourly | 12:00 – panting1:00 – 92 rpm – vet informed2:00 – 80 rpm – vet involved in care3:00 – 39 rpm5:00 – 40 rpm |

| Maintain body temperature | No usual problems | 3 | Pyrexic | Monitor hourly temperature as currently high – possibility relates to pain, infection. Inform vet at every check | Hourly | 1:00 – temp 40°C – vet informed2:00-40.1°C placed fan to try to cool3:00 – 40°C 3:38 – 39.8°C3:50 – 40°C – following ultrasound4:00 – 39.8°C5:00 – 39.7°C |

| Groom | Not usually brushed but enjoys being stroked, especially by her ears and belly | 0 | No concerns | When taking hourly TPRs, ensure that she is stroked and talked to to encourage emotional wellbeing | Hourly | 12:00 – lethargic, but responsive to TLC1:00 – less responsive2:00 – lethargic and depressed – informed vet |

| Mobilise | Slower moving around since getting older but enjoys walks and TLC | 1 | May become depressed as not at home | Ensure has comfortable bed to lie on, take out for walks every 3 hours if bright enough. Ensure she isn't just lying on one side | Every 3 hours | 12:00 – on comfortable padded bed, lying in sternal position, seems comfortable, walked outside well3:00 – lying in sternal position, condition deteriorated, not taken outside |

| Sleep/rest | Sleeps frequently throughout the day but used to noise at home | 2 | Requires critical monitoring, less opportunity to rest | Take hourly TPRs until stable, then check every 3–4 hours to ensure she has time to rest | Check hourly then 3 hourly | 12:00 – on comfortable padded bed, lying in sternal position, seems comfortable1:00 – resting well before TPR2:00 – lethargic and depressed, vet involved in care3:00 – lying in sternal position, condition deteriorated |

| Express behaviour (including pain assessment) | Happy and quiet dog at home | 3 | Pyrexic, in pain, depressed | Check pain score every 4 hours; methadone given at 11:30am | 4 hourly | 2:00 – temp 40.1°C, panting, possibly in pain. Informed vet.3:22 – Given more methadone |

KEY: Grade: 0 = normal 1 = minor 2 = moderate 3 = major

A pain score chart was not used for this patient. Morton et al (2005) demonstrated that a such a scale is a valid method of pain assessment in dogs. In 2007, Coleman and Slingsby stated that veterinary nurses agreed that pain scales were a useful clinical tool. The use of a pain score chart in this case may have led to the analgesia regimen being altered to manage pain more effectively.

Fluid therapy

IV fluid therapy plays an important role in the management of the septic patient. Septic shock is a form of distributive shock in which there is a loss of systemic vascular resistance. The patient was initially placed on Hartmann's isotonic crystalloid fluid on twice maintenance (maintenance being 2 ml/kg/hour) to correct dehydration and electrolyte imbalances. The fluid rate was increased to three times maintenance when the patient began to deteriorate to reduce temperature and heart rate. Although the patient was hypertensive, the fluid rate remained high in an attempt to try to correct the signs of shock.

Fluid therapy is used in septic patients to treat hypovolaemia, hypoperfusion and hypotension (Pachtinger and Drobatz, 2008). In septic patients, there is an intravascular fluid deficit. For crystalloids to be given effectively in shocked patients, the rate must be high enough to account for the fact that 75% of the solution administered rapidly shifts from the intravascular space into extravascular space. Traditionally, the shock rate for dogs was 90 ml/kg given in increments over 20–30 minutes (Pachtinger and Drobatz, 2008). More recently, it has been suggested that smaller volumes of 20–30 ml/kg should be administered over 20 minutes since larger volumes may affect coagulation.

Patient assessment should be performed after each bolus of IV fluid therapy to assess the need for further boluses or placement onto maintenance rates (Mazzaferro and Powell, 2013). Assessment of the effects of IV fluid therapy is usually the role of the veterinary nurse, and monitoring vital signs can help identify if the rate needs to be changed. Alongside IV fluid therapy, nurses must monitor urine output to ensure patients do not become over or under infused. It was noted during the patient's treatment when urination occurred; however, volume was not recorded. Considering Mazzaferro and Powell's (2013) guideline, the patient could have been placed on a higher fluid rate and, had urine output been specifically measured, the veterinary team may had more information on which to base decisions about the correct fluid rate.

Future considerations

One topic highlighted in the study was that pain scoring could be used better within the practice. Although available to the staff, they are not routinely used. While pain scoring has been increasingly implemented in recent years, very little evidence is available to prove its usefulness to veterinary nurses. Since analgesia can often be overlooked, it is vital that nurses are not only able to recognise signs of pain in patients but are also able to document this as evidence. In 2007, Coleman and Slingsby conducted a study into the attitudes of veterinary nurses to pain assessment and the use of pain scales. They found that 80.3% agreed that pain scales were useful but only 8.1% used them routinely in practice. Nearly all (96%) of the nurses felt they could improve their knowledge of pain management.

Coleman and Slingsby (2007) also found that veterinary nurses who had been qualified for longer tended to assign higher pain scores than those with less experience. While it was suggested that this could be down to their greater nursing experience, it does highlight the need for nurses to be educated in this area. One starting point should be the inclusion of pain scoring in student nurse training.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the importance of veterinary nurses understanding the pathology of diseases. Although clinical judgments are the concern of the veterinary surgeon, the role of the nurse remains at the forefront of care. Recognising improvements or deteriorations in a patient's wellbeing and vital signs allows nursing care to be tailored individually.

The care of a septic patient can be challenging, so veterinary nurses must ensure they keep up with changes in medical nursing to ensure their techniques are relevant and up to date. Practices may not always be fitted with the most advanced equipment, but simple techniques can be introduced routinely to improve patient care.

Key Points

- Sepsis is potentially fatal: unrecognised it can lead to secondary multi-organ dysfunction resulting in high mortality rates.

- Understanding the pathophysiology of septic shock is vital to ensure care is specifically tailored to the patients individual needs.

- Pain management should be classified as the fourth vital sign.

- Fluid therapy is used in septic patients to treat hypovolaemia, hypoperfusion and hypotension.

- Basic monitoring is used by veterinary nurses to spot trends in a patient's recovery, so care can be tailored quickly and effectively.