The terms ‘obese’ and ‘overweight’ are based on an animal's current bodyweight relative to an ideal bodyweight. Although using an animal's body fat index (BFI) as a measure of ideal weight is more accurate than bodyweight, bodyweight remains easier to measure in a routine practice setting (Toll et al, 2010). An animal's current weight divided by an estimation of its ideal bodyweight is defined as its relative bodyweight (RBW). A dog is considered obese when its RBW is greater than 20%, and overweight with its RBW is greater than 10% (Toll et al, 2010). According to a 2010 UK veterinary practice survey, slightly over 59% of dogs were classified as overweight or obese (Courcier et al, 2010). Being overweight or obese is a disease and is thought to be the most prevalent form of malnutrition found in veterinary practice (Brooks et al, 2014). Canine obesity increases risk and prevalence of metabolic disorders, endocrine disease, reproductive disorders, cardiopulmonary disease, urinary disorders, dermatological disease, and neoplasia (Table 1) (German, 2006; Toll et al, 2010). A 25% lifetime reduction in food intake has demonstrated a significantly increased median lifespan, and delayed the onset of clinical signs associated with chronic disease (Kealy et al, 2002). A successful obesity treatment protocol should incorporate a plan for both weight loss and weight maintenance.

| Metabolic alterations | Functional alterations |

|---|---|

| Anaesthetic complications |

Decreased immune function |

| Endocrinopathies | Other diseases |

| Diabetes mellitus |

Altered kidney function |

Patient management

In order to develop a successful canine weight loss plan, the following steps are critical:

Diet and medical history

Obesity cannot only predispose a dog to multiple diseases, but can also be a result of a disease or disorder, such as hypothyroidism or other endocrinopathies. A thorough medical history provides an understanding and background of previous illnesses. A diet history should be taken at each visit. When a diet history is combined with a medical history, trends can be monitored and illnesses can be detected earlier. Diet history should include more than simply the name of the food and the amount being fed per day. It should also include the flavour and form, number of times fed per day, treats, dental chews, supplements, food used for medications and any human food consumed (Pet Nutrition Alliance, 2018a). It is a way to better understand how the client, pet and household interact with food (Michel, 2009). Obtaining such detail from a client takes practice and may at first seem time consuming. The process can be made more efficient by using a diet history form (American College of Veterinary Nutrition (ACVN), 2016). A history form such as the example provided by ACVN (Appendix 1. http://www.acvn.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/ACVN-Diet-History-Form.pdf) allows a conversation to occur between the owner and the veterinarian or veterinary nurse. This provides a better understanding of owner preferences in regards to feeding their pet.

Household and activity Level

The ACVN diet history begins with a discussion of the pet's household. Is the pet mainly indoors and sedentary? Alternatively, is it mainly outdoors and active? Or is it indoors but walked frequently? Are there small children in the house that provide access to frequent snacks for the dog to find on the floor? Are there other pets that are fed separately? Are the pets fed together? What other food sources are available to the pet? These are all very important questions that help determine the correct energy demands of a pet in the nutritional plan.

Diet, supplements and medications

Gather information on the specific diet brand, form, amount and frequency. Include questions surrounding nutritional supplements and any medications given to the pet. If medications are given disguised in food, how much and what is being given? There are times that pet owners will not have this information on hand or recall the exact brand of food or supplements given (Michel, 2009). They will need to check the label of the food and provide the information later. Owners often underestimate the amount of measured food given. If the owner is not sure of the amount, the clinic can send the owner home with a measuring cup and have the owner provide this information after the visit.

Treats

Owners have different terminology for treats and sometimes determining if a pet is getting treats can be very difficult and not always straightforward. Questions surrounding treats should be asked several times in multiple different ways (Michel, 2009). According to Michel (2009), treats include commercial treats, human food, table scraps, dental treats, and food provided for environmental enrichment.

Current weight and weight trends

A weight should be recorded at every visit in addition to the pet's body condition score (BCS). This allows for monitoring of both feeding and weight trends (Pet Nutrition Alliance, 2018a).

BCS and body fat index (BFI)

The BCS subjectively evaluates body fat (Freeman et al, 2011) and takes into account its body frame (Toll et al, 2010). There are multiple scoring systems available; however, WSAVA has adopted the 9-point scale (Figure 1) (Freeman et al, 2011). In addition to multiple scoring systems, the BCS is a learned skill based on defined criteria (Toll et al, 2010). Caution should be taken to ensure that all members in a practice are using the same BCS scale and criteria in recording measurements. When the BCS is proficiently learned it can be a reliable indicator for determining body composition in dogs up to 40% body fat (Mawby et al, 2004; Toll et al, 2010).

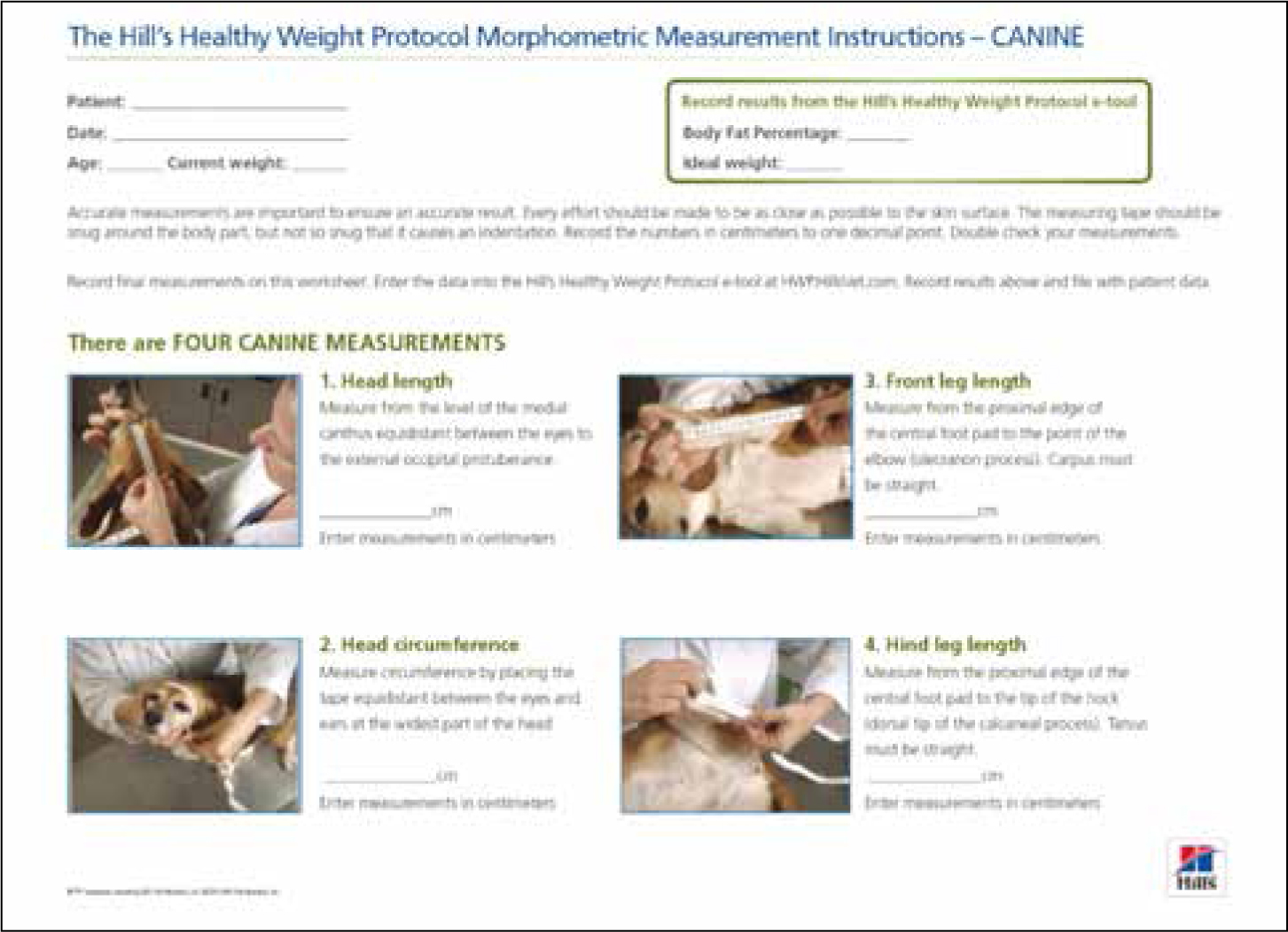

For pets greater than 40% body fat, morphometric measurements and the BFI appear to be more accurate (Figure 2) (Witzel et al, 2014). In order to determine the BFI, a series of morphometric measurements is conducted. Once the measurements are obtained, the data are entered on an e-tool provided through Hill's Pet Nutrition to obtain the pet's BFI (Hill's Pet Nutrition, 2012c).

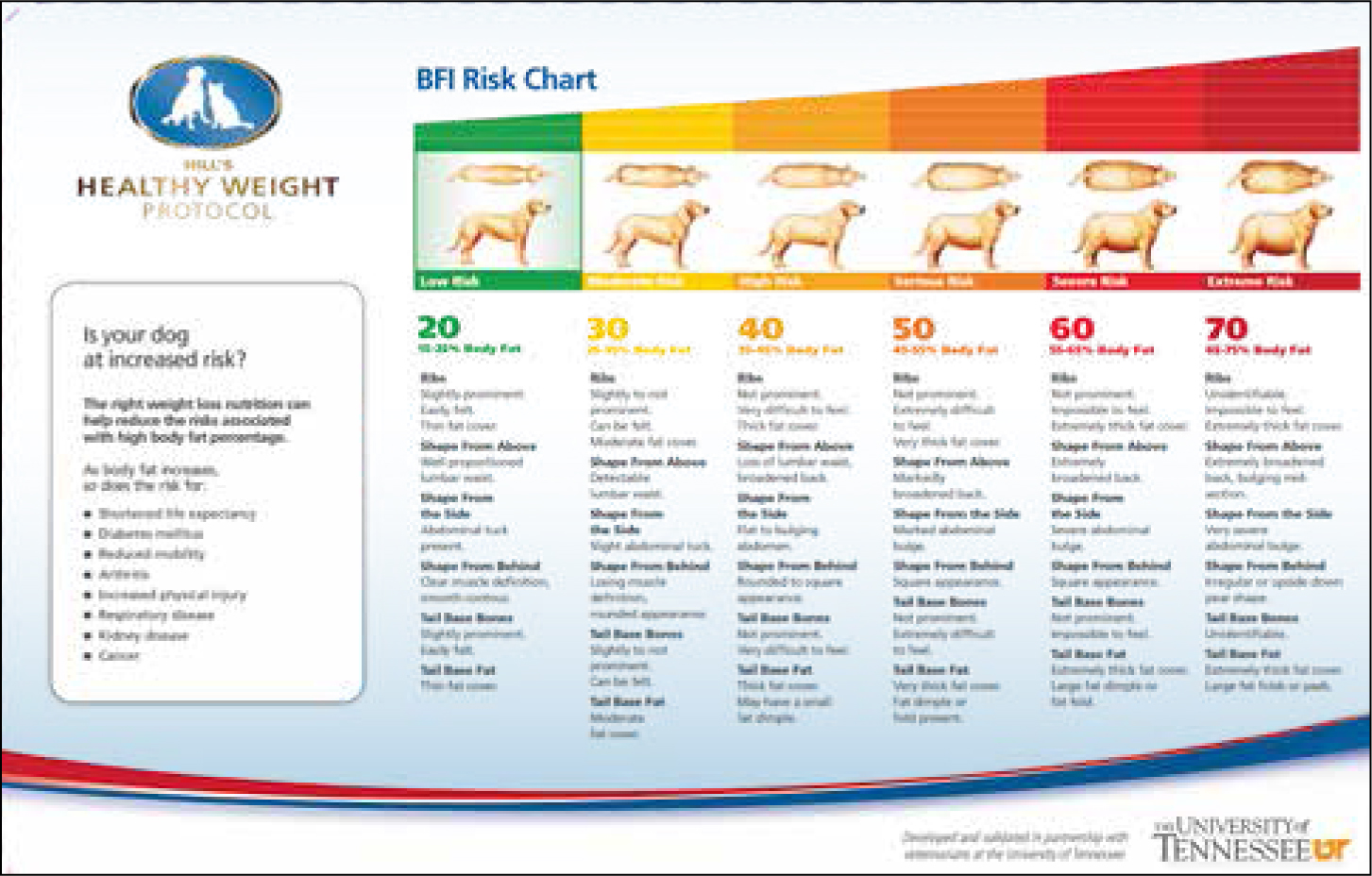

A dog's BFI may also be estimated or explained using similar criteria as a BCS using the Hill's Pet Nutrition BFI Risk Chart (Figure 3).

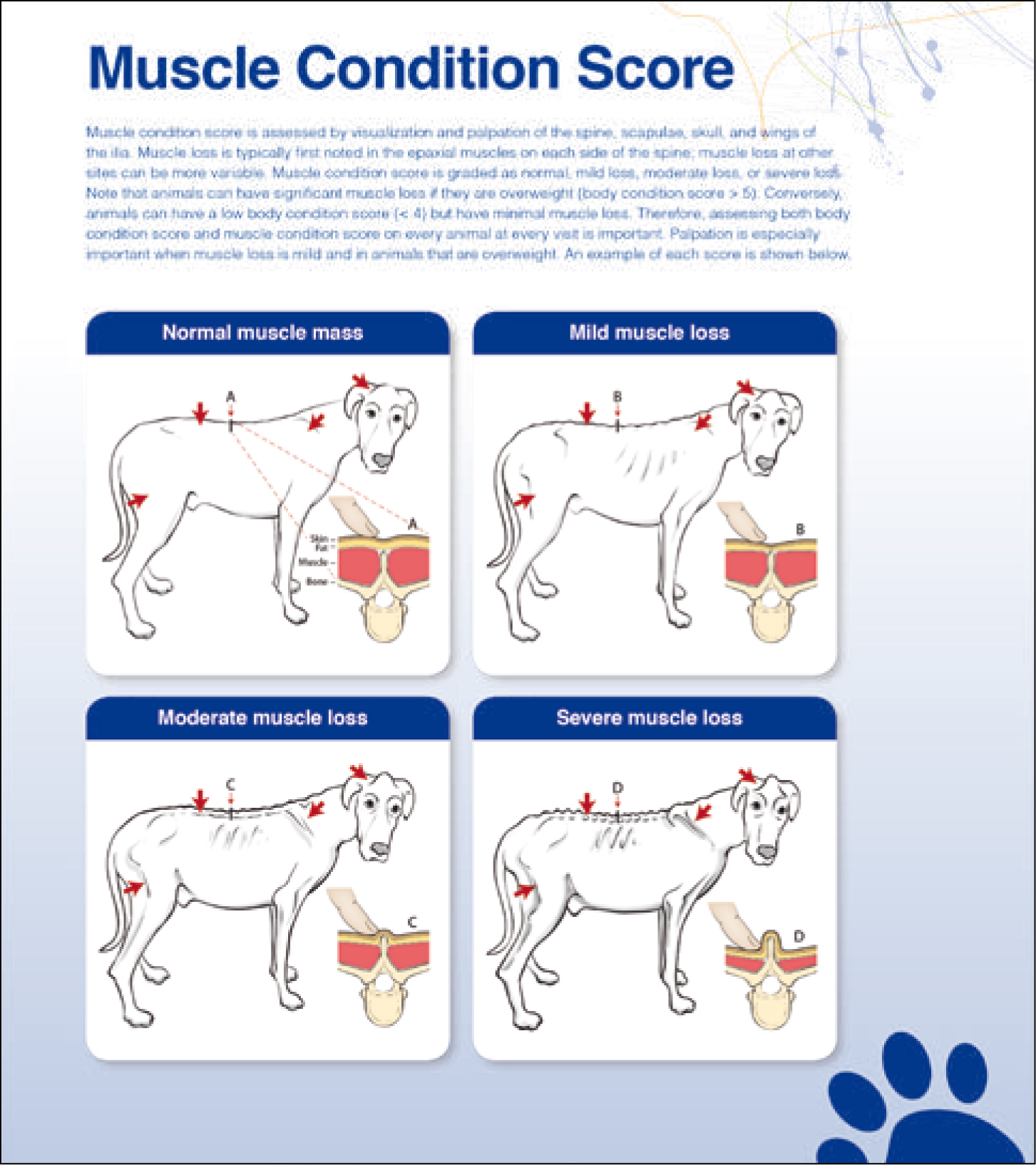

Muscle condition score (MCS)

The assessment for lean body mass is the MCS (Figure 4). The MCS should be used in conjunction with the bodyweight and BCS/BFI (Pet Nutrition Alliance, 2018a). Determining the MCS involves visual examination and palpation over four bony prominences (Freeman et al, 2011):

Development of a feeding and exercise plan

Once the percent body fat (%BF) is estimated with the BCS and/or BFI, an ideal bodyweight (BW) can be determined. (Toll et al., 2010)

Ideal BW = current weight X (100 – %BF)/80

Once an ideal bodyweight is calculated, the caloric demands and food choice are made. This can be done using a standard nutritional calculation (Tables 2 and 3).

| Using ideal bodyweight to determine initial food dosage for controlled weight loss |

|---|

| The following steps represent the process for estimating the initial amount to feed for weight loss using ideal bodyweight: |

| Two alternative methods for estimating resting energy requirement (RER) |

|---|

|

|

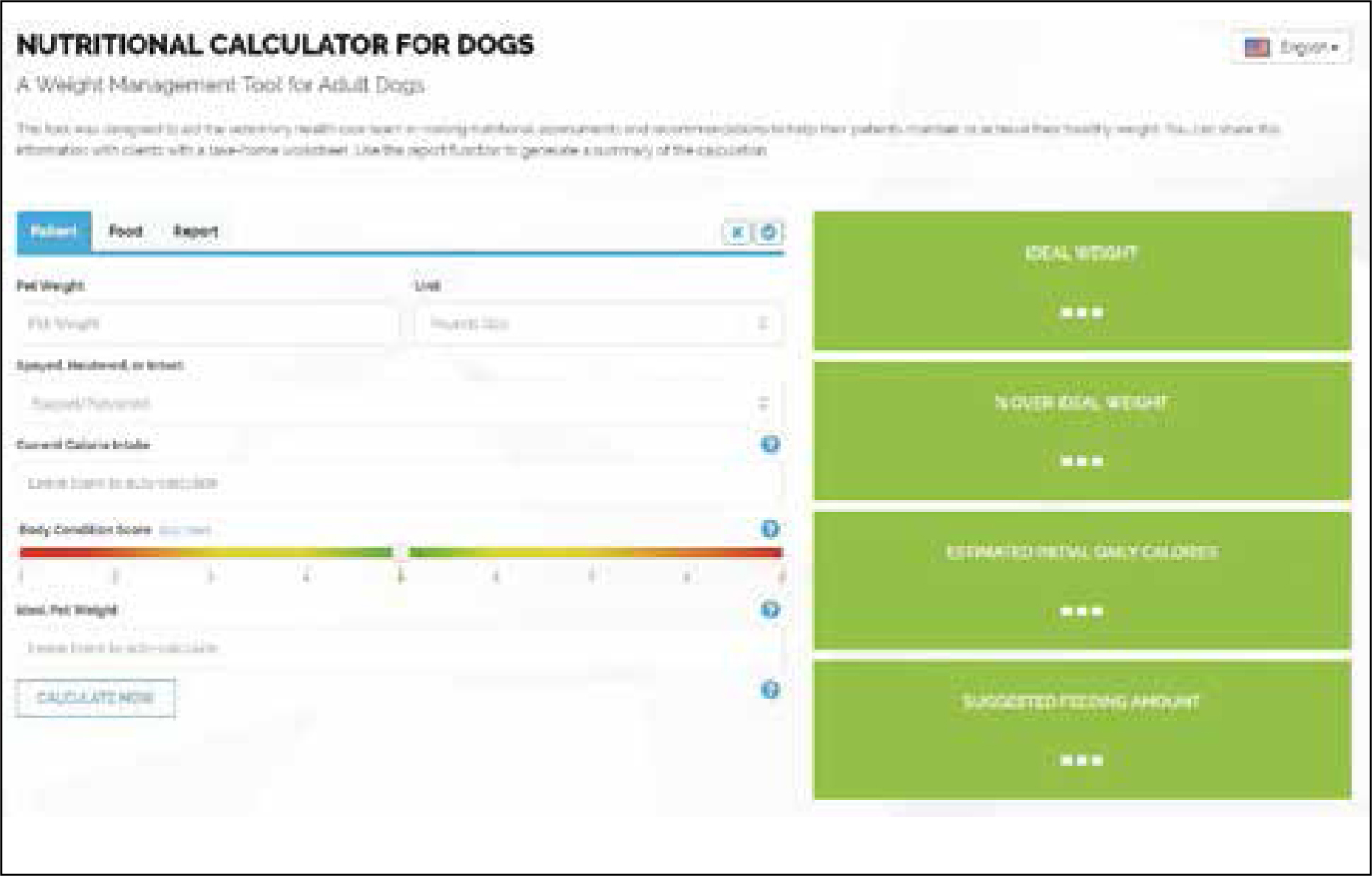

The Pet Nutrition Alliance has developed an on-line nutritional tool to help ease the confusion of the calculations described in Tables 2 and 3 (Pet Nutrition Alliance, 2018b) (Figure 5).

A food with a reduced energy density should be considered as opposed to reducing the amount of a dog's normal food. The reasoning is that most maintenance foods are nutritionally balanced according to the calculated intake to meet a healthy/normal weight pet's nutritional needs. If the amount of a diet is reduced the intake of energy is reduced but also the total amount of nutrients (Toll et al, 2010). Toll et al (2010) recommends feeding an energy restricted food that still delivers sufficient amounts of protein, essential fatty acids, and vitamins/minerals needed for normal physiologic processes and lean muscle mass maintenance.

An exercise plan should be incorporated into a weight loss programme. All exercise should be introduced slowly determined on what a dog can tolerate. Fifteen to 30 minute walks, five to seven times a week, are a good start (Toll et al, 2010). Daily energy requirements of dogs increase by 5–7% when walking a total of 5 km/day (Toll et al, 2010).

Nutritional coaching and weight rechecks

All members of the veterinary healthcare team can help the client feel at ease as they begin the weight loss journey with their pet. It is important that active communication with the client continues after the appointment and that recheck weigh-ins are proactively scheduled. Efforts of continued communication will demonstrate ongoing support of the client while building trust with the client and the veterinary healthcare team (Linder, 2017).

Weight rechecks are an essential part of a successful weight loss programme, accomplishing the following (Toll et al, 2010):

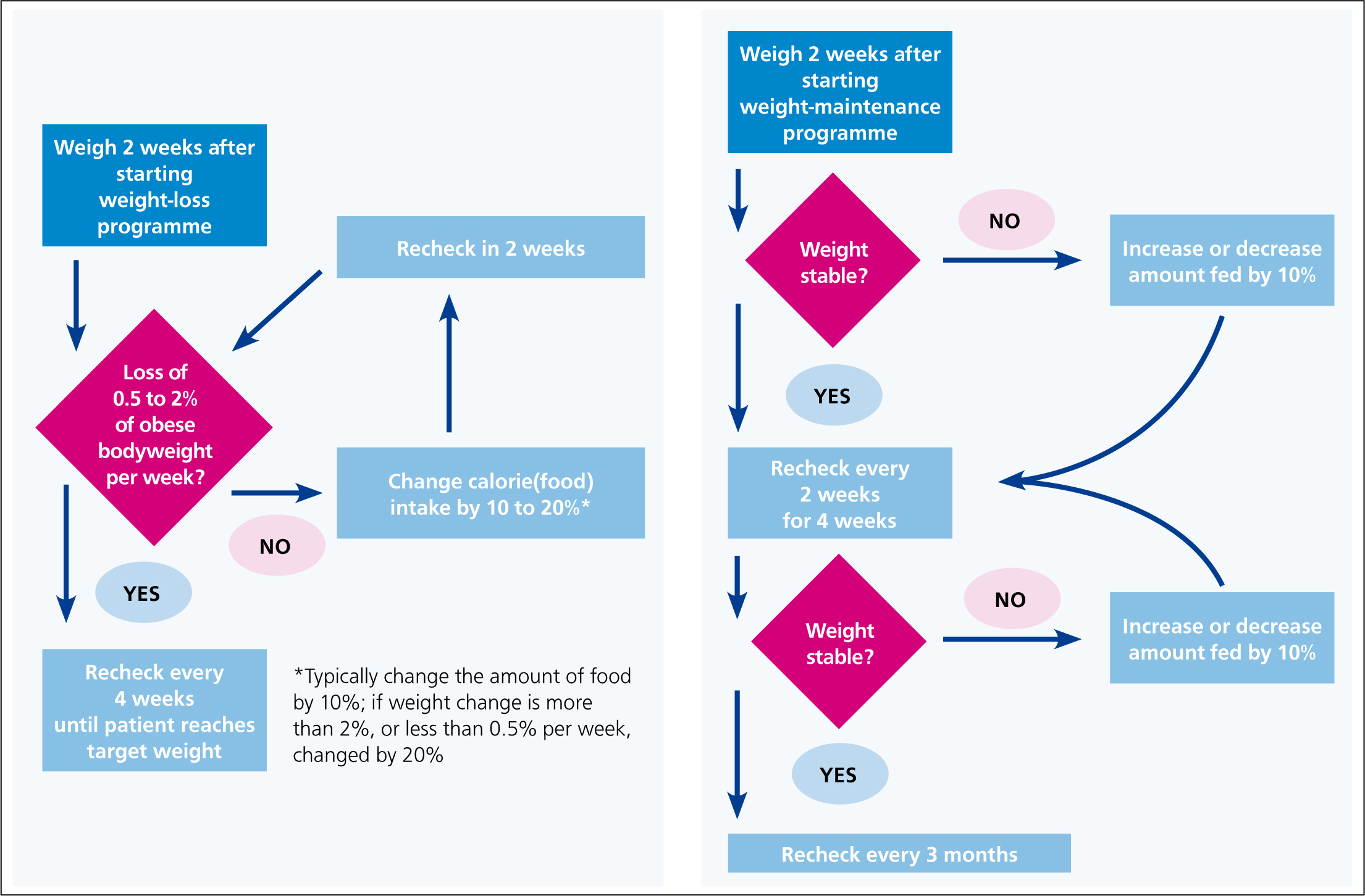

Schedule the first weight recheck for 2 weeks after the nutritional plan begins. Make feeding adjustments based on the algorithm in Figure 6.

Weight loss for obese and overweight canines should range from 0.5 to 2.0% of initial bodyweight per week (Toll et al, 2010). These guidelines are helpful not only in making adjustments to feeding and exercise plans during weight loss, but also in communicating to the client the anticipated time for their pet to reach its goal weight. Once the goal weight is achieved, it is vital that a supervised weight maintenance programme is initiated. The weight maintenance programme includes continued nutritional coaching and weight rechecks.

Conclusion

Canine obesity is becoming an epidemic problem in modern industrialised societies. Overweight and obese dogs are predisposed to diseases and disorders that ultimately shorten their lifespan. Simply instructing owners to decrease the amount they are feeding their pets is not a successful approach. In order to be successful, one must obtain a complete nutritional history and assessment, and perform a physical examination that includes a BCS and MCS. Finally, it is essential to provide a flexible nutritional plan with scheduled rechecks and ongoing coaching.