As animals age, changes to multiple organ systems occur that require knowledge from the veterinary team to facilitate adjustments. The changes to these important systems are often not evident to pet owners; studies have shown that clinically significant changes have occurred in up to 30–80% of ‘healthy’ geriatric dogs (Willems et al, 2017). Pet owners often miss common changes and on veterinary examination and laboratory test, changes such as polyuria/polydipsia, changes in urination habits (like stranguria or pollakiuria), weight changes, orthopaedic changes, dental disease, and liver and kidney enzyme elevations are discovered (Willems et al, 2017).

Veterinary teams need to ensure that pet owners are educated on the importance of regular physical examinations and closely observing their pets, watching for changes to appetite and behaviour at home. Prior to coming to the hospital for any anaesthetic event, geriatric pet owners should receive directions tailored to their pet's specific needs. Any fasting for these animals should be reduced to only 4–6 hours (Grubb et al, 2020). A small meal can be offered in the morning to help reduce gastro-esophageal reflux. All chronic medications such as thyroid, behaviour modification, steroids, antibiotics, and analgesics should be given as normal. Cardiac patients should not receive their angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors the morning of anaesthesia and insulin should be discussed with the veterinary surgeon (Grubb et al, 2020). Stress and anxiety should be avoided as much as possible and can be reduced by administering gabapentin (30–60 mg/kg in dogs; 10 mg/kg up to 100 mg/cat in cats) 1–3 hours prior to arrival at the hospital. It is important for the team to ask about and then record the use of gabapentin, as morphine and hydromorphone have been shown to increase gabapentin activity, and gabapentin can decrease the activity of morphine and hydromorphone (Cirribassi and Ballantyne, 2019).

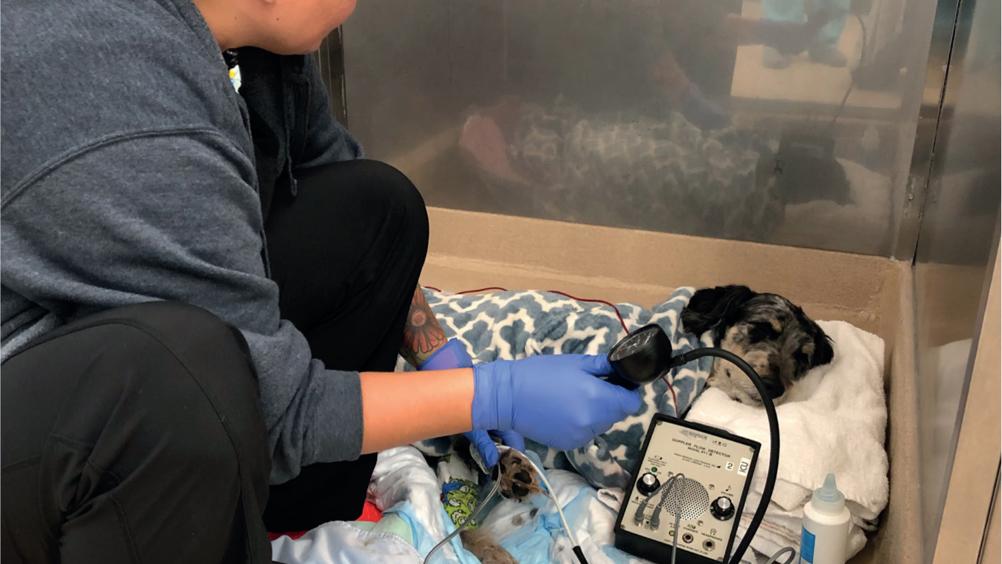

When these pets present to the hospital and require anaesthesia, a geriatric-focused clinical examination should be performed. In addition to a complete patient history and physical examination, and prior to any anaesthetic event, a blood pressure measurement (Figure 1) and ophthalmic examination should be completed (Willems et al, 2017). These pets should also have a full complete blood count and blood chemistry panel, urinalysis, and thoracic radiographs considered prior to anaesthetic induction (Robertson, 2018).

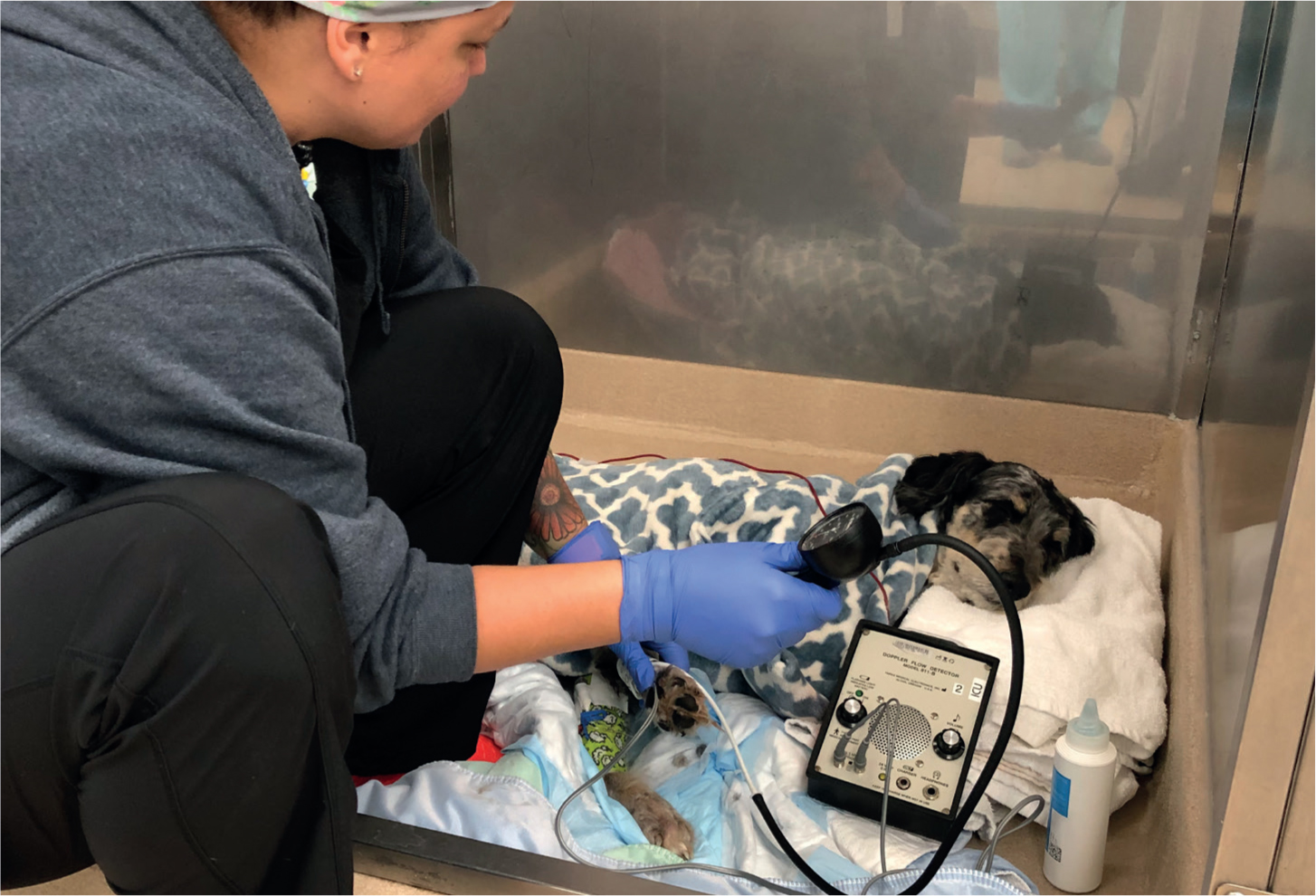

Once examined, an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score 1–5 should be assigned to each patient (Waring, 2017). This score can be used to guide discussions regarding premedication, anaesthetic protocol, and recovery plan, and these can be adjusted as needed. The veterinary team should use the nursing process during all steps of the anaesthetic process — assessment, planning, implementation and evaluation — to ensure that changes are recognised and emergency plans are ready (Caldwell, 2020). Emergency drug doses including any reversal drugs should be checked and all tools and equipment ready pri- or to induction to ensure a smooth event and recovery (Figure 2) (Robertson et al, 2018). All patients, regardless of age, should have an intravenous (IV) catheter placed and maintained during deep sedation or anaesthesia (Grubb et al, 2020).

When finalising an anaesthetic protocol for geriatric pets, careful consideration is needed. For pets who are older than 12 years, the risk of anaesthetic death increases by as much as seven times (Grubb et al, 2015). This statistic is not meant to scare off veterinary teams, nor owners, but should serve as a reminder that close attention to these patients must be paid (Figure 3). Age can cause changes to multiple organ systems requiring adjustments from the veterinary nursing team (Table 1).

Table 1. Organ system changes and required adjustments by veterinary nurse

| System | Changes | Required adjustments |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiac |

|

|

| Respiratory |

|

|

| Central nervous system |

|

|

| Renal |

|

|

| Hepatic |

|

|

| Musculature |

|

|

| Metabolism |

|

|

Keeping all of these changes in mind, it is clear to see the importance of multimodal anaesthetic protocols where multiple classes of drugs can work together, at smaller doses, to achieve anaesthetic goals. When possible, drugs should be titrated to effect so that only what is needed by the patient is administered. If possible, medications that can be reversed should be used so that if the patient has a greater response than desired, the drug can be reversed (Grubb et al, 2015).

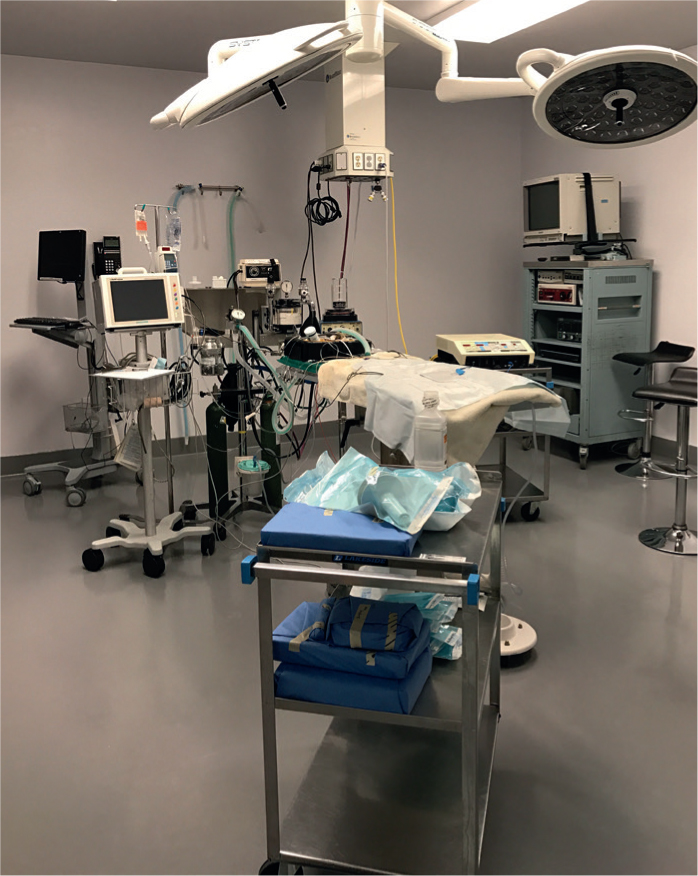

Once anaesthetised, close monitoring is required of all patients. At minimum, there should be a dedicated anaesthetist who is monitoring for patient movement and reflexes, pulse quality, heart rate, capillary refill time, mucous membrane colour, blood pressure, pulse oximetry, end-tidal CO2, and body temperature. All of these parameters should be recorded at least every 5 minutes. Anaesthetists should be comfortable with normal vital signs and how to troubleshoot abnormal responses (Figure 4) (Robertson et al, 2018). Treatment for tachycardia, bradycardia, hypoventilation, hypotension, and hypothermia should be discussed prior to anaesthetic induction, so that treatment can quickly and efficiently begin should any of those abnormalities occur.

Care should be given to patient positioning both intraoperatively and postoperatively. The team must use caution not to overstretch joints or create pressure points during long procedures. Padding and support should be given in the operating room, and generous bedding given for recovery. These animals may need extra support when standing and walking again after a period of recumbency (Robertson et al, 2018).

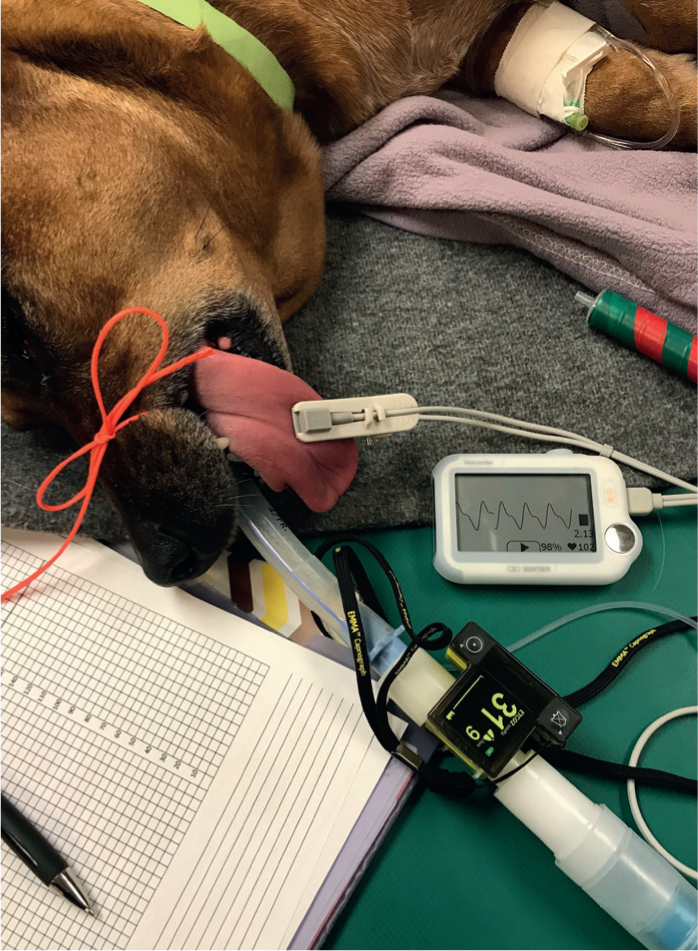

On anaesthetic recovery, close attention must be paid to the patient. According to the doctoral dissertation, The Confidential Enquiry into Perioperative Small Animal Fatalities, 50% of perioperative deaths occurred within 3 hours of discontinuing anaesthesia (Brodbelt, 2006). To the veterinary nursing team, this means that after discontinuing the close monitoring of general anaesthesia and after extubation the patient must be watched closely. Flow-by oxygen can be beneficial until the patient is awake and alert (Figure 5). All vital parameters should be monitored until they are normal; this includes heart rate, respiratory rate and effort, mucous membrane colour, capillary refill time, pulse quality, blood pressure and body temperature. Vital parameter monitoring should continue at frequent intervals (at least every 15 minutes) as the patient recovers. Active warming may be required during recovery and should be continued until the body temperature is normal, as well as checked after removing the heat source to ensure the patient is able to maintain a normal body temperature (Figure 6). IV fluids may not need to be continued beyond general anaesthesia and the decision on fluid therapy should be made according to the patient's perfusion, hydration, and blood pressure. Especially with geriatric and critical patients, a veterinary nurse should remain close by until the patient regains full consciousness and can sit in sternal recumbency (Robertson et al, 2018). Pain management must not be ignored at any point (Figure 7). Pain scoring should be used to determine patient need for additional or continued pain management as pain can deter healing and prevent the patient from returning to normal eating habits.

Conclusions

Hospitals should create not only anaesthetic drug protocols for geriatric patients, but also pre and postoperative care instructions for staff and pet owners to ensure high-quality care and monitoring outside of hospital. Pet owner anxiety exists around all anaesthetic events, but especially when the pet is older. The veterinary nursing team can address these concerns with thoughtful, empathetic, and knowledgeable answers, to reassure the owner that their pet will be given great care while in hospital.

KEY POINTS

- As pets age, multiple organ systems undergo changes that require adjustment prior to anaesthesia.

- Geriatric-focused physical examinations should be performed prior to creating an anaesthetic plan.

- Anaesthetic monitoring should be tailored to the specific changes that occur in geriatric and ageing pets.

- During the anaesthetic recovery period, geriatric pets should be monitored closely by a dedicated veterinary nurse.

- Client education both pre and postoperatively is instrumental in client compliance and comfort during the procedure.