Feline ovariohysterectomy (spay) is a common routine procedure recommended for female cats in order to control population growth (Andersen et al, 2004). It is therefore a routine procedure carried out daily in veterinary practice. Anecdotal observations suggest that post-operative pain relief from feline ovariohysterectomy is generally not as well monitored in terms of assessing pain when compared with procedures such as orthopaedics. Pain scoring however is a useful tool which should be used more routinely by veterinary nurses in practice for both hospitalised and routine procedures. A study by Coleman and Slingsby (2007) found that only 8% of practices used a pain scoring system routinely.

There are a number of different types of pain scales including the visual analogue scale (VAS), the dynamic interactive visual analogues scale (DIVAS) as well as simple descriptive scale (SDS). This study looked at two of the pain scale models (DIVAS and SDS) used in practice. This blind study compared the use of each pain scale model pre and post operatively on feline patients undergoing surgery for ovariohysterectomy, to ascertain pain score level accuracy. By assessing this area of post-operative care a deeper understanding can be developed of the importance of assessing pain level after routine procedures particularly in felines, which are considered more challenging to assess (Barratt, 2013).

Literature review

Pain scoring has been identified as an area in the past that has required further development. A historical study by Lascelles et al (1999) concluded that 68% of veterinary surgeons felt that nurses had insufficient knowledge of pain; the study also found that veterinary surgeons themselves gave different species a different frequency of analgesic with dogs receiving more than cats despite the same procedure being carried out. The issue of individual differences in observation can also make pain scoring inconsistent and a subjective process. Capner et al (1999) found that female veterinary surgeons assigned higher pain scores to surgical procedures than males. This perhaps showed that female veterinary surgeons showed more empathy towards patients than male veterinary surgeons (Capner et al, 1999).

More recent research demonstrates a similar trend. Coleman and Slingsby (2007) conducted a study which found that veterinary professionals gave lower pain scores to cats undergoing surgical procedures when compared with dogs undergoing similar procedures. The study determined that empathy for cats was less than for dogs, and that knowledge of pain assessment needed to improve. The study also found that only 8% of practices up until 2007 were using a pain scoring system despite it being considered a useful clinical tool.

Barratt (2013) discussed the difficulties surrounding cats and pain scoring and the lack of validation within feline pain score systems to date. Despite the lack of validation in cats, pain scores still encourage frequent evaluation of patients, as well as assisting in standardising such methods of assessment. The Colorado State University scale (http://www.vasg.org/pdfs/CSU_Acute_Pain_Scale_Kitten.pdf) is the first dynamic and interactive visual analogue scale to assess acute pain in felines (Barratt, 2013) and is similar to the Glasgow composite measure pain score used in dogs. There are several studies (Slingsby and Waterman-Pearson, 1998; Muir and Gaynor, 2002) on the Colorado pain scale that support the scale in terms of its effectiveness and its incorporation of both physiological and behavioural assessment into one scale.

Crompton (2014) carried out a review on current pain score research and found that the use of pain scales should be an integral part of an animal's post-operative evaluation, reflecting Coleman and Slingsby (2007) whose findings determined that 80% of nurses found pain scales useful in providing quality nursing care. Factors which are important in aiding pain assessment include the use of physiological signs as well as behaviour. The use of behaviour for pain assessment is embedded into the VAS scale making this the most popular choice of pain scale; the Colorado State University scale is included within this category (Crompton, 2014). A human study supporting use of the scale was carried out by Bijur et al (2001) which concluded that a VAS scale when used for acute pain was deemed reliable with 90% of pain ratings accurately assessed within 9 mm. However, Holton et al (1998) criticised the scale stating that the use of a 100 mm line which represents a scale from ‘no pain’ up to ‘worst possible pain’ is inaccurate for individuals to score effectively the pain of a patient. Grant (2006) agreed, criticising the Colorado scale for the ease of ‘jump’ from one number to the next.

Different pain scores may also suit certain practices due to time constraints and staffing issues, in addition all veterinary staff should receive training on the use of pain scores which they will be using and should be confident in its application in order for it to effectively assess level of pain accurately (Rooney, 2014). A further consideration is the difficulty in detecting pain within each individual due to differing natures, pain experiences, conditions and pain thresholds (Bloor, 2012). The study reiterates the importance of vigilance within the veterinary nursing team. Suggestions include that one nurse is responsible for the pain score of the patient or that there is agreement between various nurses to ensure no pain is missed due to subjective interpretation or observer error (Bloor, 2012).

A flurry of research was conducted around the late 1990s to early 2000s when pain scoring was just starting to be introduced into the veterinary field, and due to advancements in the nursing profession, in particular the desire for more evidence-based research, this field of study is seeing a revival. This study aims to compare the use of two feline pain scoring scales implemented in practice to evaluate accuracy in assessing pain between the two models.

Methods

Ethical consent was gained by Askham Bryan College. 14 entire female cats were selected, age range 6 months to 3 years and weighing between 2 to 4 kg. Each cat was randomly assigned to a pain scale either the ‘Colorado State University feline acute pain scale’ or the ‘Vetergesic composite pain scale for cats’, seven cats within each category.

Prior to surgery each cat underwent a pre-operative pain score measurement alongside a health check. Any patient that showed signs of pregnancy was removed from the study. A kennel was randomly assigned to each cat. The cats were given time to settle into their new surroundings before the pre-operative pain score was carried out.

Each cat was pre-medicated using a ‘triple combination’ of medetomidine (Domitor, Pfizer Animal Health), butorphanol (Torbugesic, Zoetis) and ketamine (Narketan, Vetoquinol) given intramuscularly. All cats were then intubated and maintained under oxygen and isoflurane and reversed using atipamizole (Antisedan, Zoetis). The surgeries were carried out by several veterinary surgeons. One person performing all the procedures may well have controlled any confounding variables in regards to suture tension and length of surgery, however this was not possible and all procedures took a similar length of time. A pre-emptive analgesic of a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) (meloxicam) was also administered subcutaneously prior to surgery.

Each cat was clipped and cleaned on the left flank and underwent an ovariohystercetomy. All received intra-dermal stitches using the same suture material.

Post operatively, the cat's pain level was scored at 30 minutes post extubation followed by every hour for 3 hours. Each pain score reading was carried out by the same observer ensuring reduced error and increasing validity of the study.

The two pain scales had different numerical ranges. The Vetergesic pain scale ranged from 0–24, the Colorado State University scale from 0–4. In order to compare the data effectively, the Colorado pain scale was converted into a scale which matched the Vetergesic pain score by multiplying the results by six. Statistical analysis was performed using ‘Minitab’ using non parametric tests (Mann-Whitney U).

Results

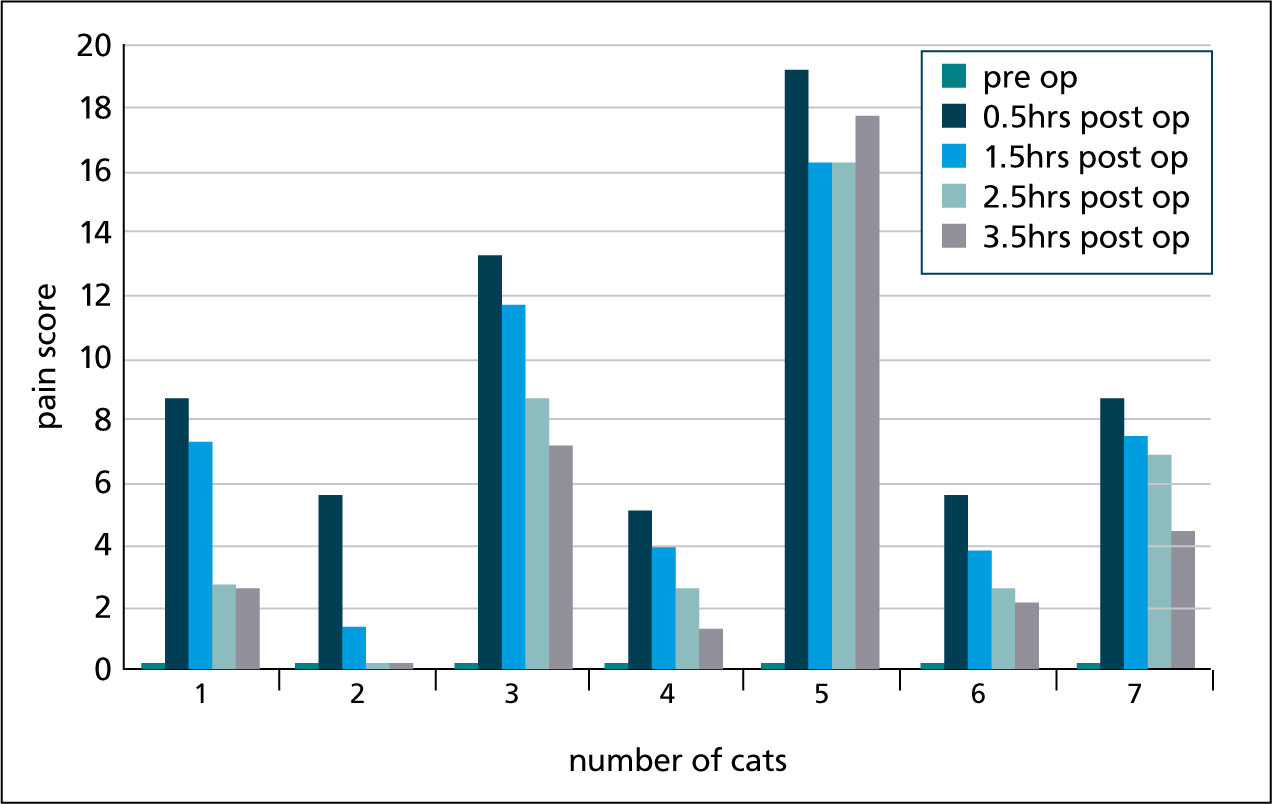

Colorado pain

scale Over the time period in recovery six out of seven cats' pain score decreased over each of the five checks. The highest pain score for all cats was assigned at 30 minutes post ovariohysterectomy with cat number five showing a slightly higher pain score at 3 hours 30 minutes than its previous two pain scores (Figure 1).

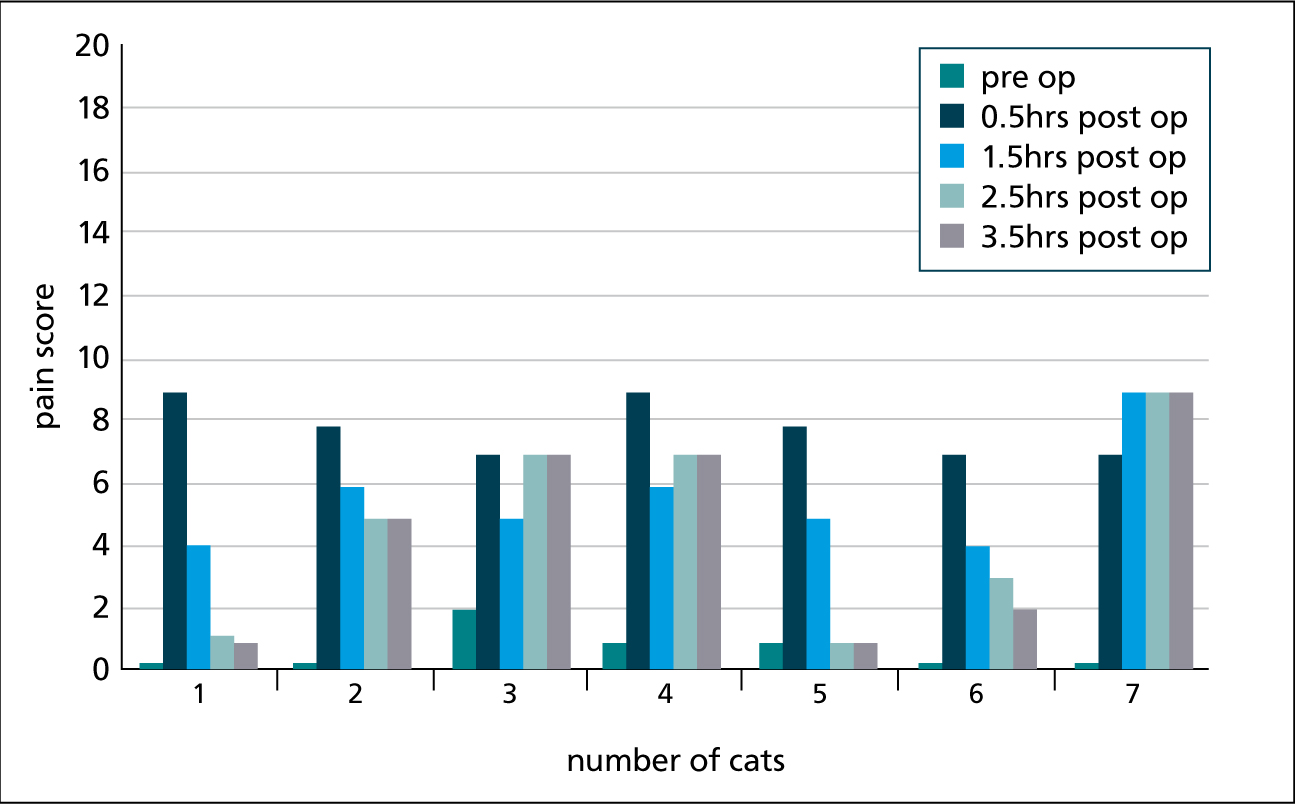

Vetergesic pain scale

The highest pain score for six out of seven cats was assigned at 30 minutes post ovariohysterectomy. Four out of seven cats' pain score decreased over the five time intervals with cat number three, four and seven showing a higher pain score at 2 hours 30 minutes and 3 hours 30 minutes (Figure 2).

Comparison of the scales

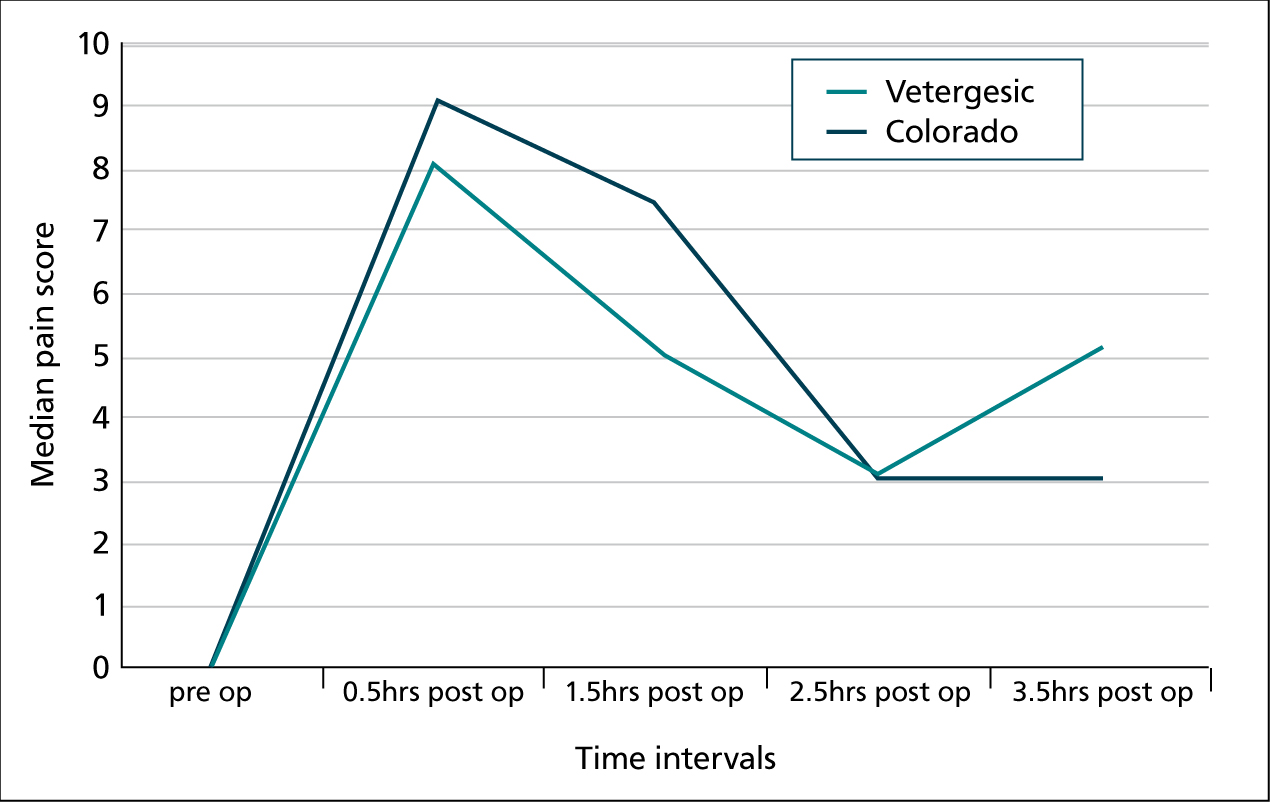

The accuracy of the pain scale rating was then compared for each of the pain scales used (Figure 3). At each post-operative pain score, the results produced a p value of >0.05. This suggests that there is no statistically significant difference between using the Vetergesic pain scale and the Colorado pain scale and that they are therefore both an accurate reflection of the cat's level of pain during each time interval assessing pain of cats undergoing ovariohysterectomy.

Discussion and limitations of the study

The Vetergesic composite pain scale for cats and the Colorado State University feline acute pain scale both used a different technique in order to effectively pain score feline patients. The use of a SDS by the Vetergesic scale uses factors such as mental state, feeding/appetite and activity of the patient. The use of DIVAS offers only a numerical scale of 1–4 to choose where the cat should be positioned.

It is important to note that each individual patient is different and that many cats attempt to hide pain due to their natural behaviour (Mercado, 2009). Responses to pain can vary significantly due to factors such as tolerance of pain, and also as a result of new environments (Wright, 2002).

This limitation can be seen in the results from the Colorado pain score (DIVAS) with cat number five having a significantly higher score at each time period than any other patient recorded. It was noted at the time that the cat was stressed, indicated by hiding behaviour.

A similar trend was seen in cats three, four and seven from the Vetergesic pain score (SDS). In particular, cat number seven showed an increase in pain score after the 30 minute post-operative check right up until its last pain score time interval. The SDS however allows for more factors related to stress and the environment than the DIVAS, so it was initially expected that this pain score would give higher results than the Colorado.

Conversely, when the median pain score was calculated for both the Colorado and Vetergesic scale at each time interval, the results were similar both following a decreasing trend up until the last time interval of 3 hours 30 minutes. A further limitation included sample size. Use of seven cats per pain score is not sufficiently large, so reliability of these results could be questionable.

From the statistical analysis comparing the accuracy of the pain scale rating between the two scales used, the p value was >0.05. This suggests that overall there is no statistically significant difference in accuracy between the two pain scales, giving veterinary professionals some confidence that whichever pain score scale they choose to utilise, they are as accurate as each other in assessing pain level. These results are in line with Slingsby and Waterman-Pearson (1998) and Waterman-Pearson (1999).

The increase in pain score at later time intervals may be due to the analgesic properties of butorphanol from the premedication dissipating, or the reversal of the premedication affecting pain levels. It could also lead to a discussion of whether monitoring pain for a longer period should be considered? At least one cat from each scale had an increase in pain score at later time intervals raising the question, should nurses monitor patients as closely as patients recently extubated at 3 hours post-operatively? Considerations should be made as to whether longer post-operative monitoring is beneficial for the patient or whether prolonged monitoring causes the increase in score due to handling and stress (Mercado, 2009). The global pain council set guidelines for canine post-operative monitoring recommending every 15 to 30 minutes and on an hourly basis thereafter for the first 6 to 8 hours (Hall, 2015).

The results show that the differences between the Vetergesic pain scale and the Colorado pain scale in scoring feline ovariohysterectomy patients are minimal regarding accuracy of assessing pain level. Ease of use should be assessed by each practice and whichever pain score technique is employed, staff should be trained in its use to ensure a standardised approach to pain assessment. It is important to bear in mind that there can be limited conclusions drawn within this study due to the small sample size.

Conclusions and suggestions for future research

The uses of feline pain scoring systems within the study were concluded to be of benefit to the ovariohysterectomy patient. By using such scales, it allowed detection of abnormal behaviours.

The results showed that despite the use of two very different scales SDS and DIVAS, both resulted in an accurate reflection of the level of pain. Ease of use should be determined within practice as both methods of pain scoring have equal strengths and weaknesses. Either way staff should receive adequate training in order to ensure either scale is used to its full potential.

Future research suggests increasing sample size to address individual variation within each patient as well as determining if the same results occur in regards to assessing accurately pain. In addition a comparison of other pain scales to one another would also be advantageous as well as determining how many practices are now routinely using pain scores of their hospitalised and surgical patients in order to increase animal welfare and practice evidence-based medicine.