Behavioural first aid advice for canine patients

Abstract

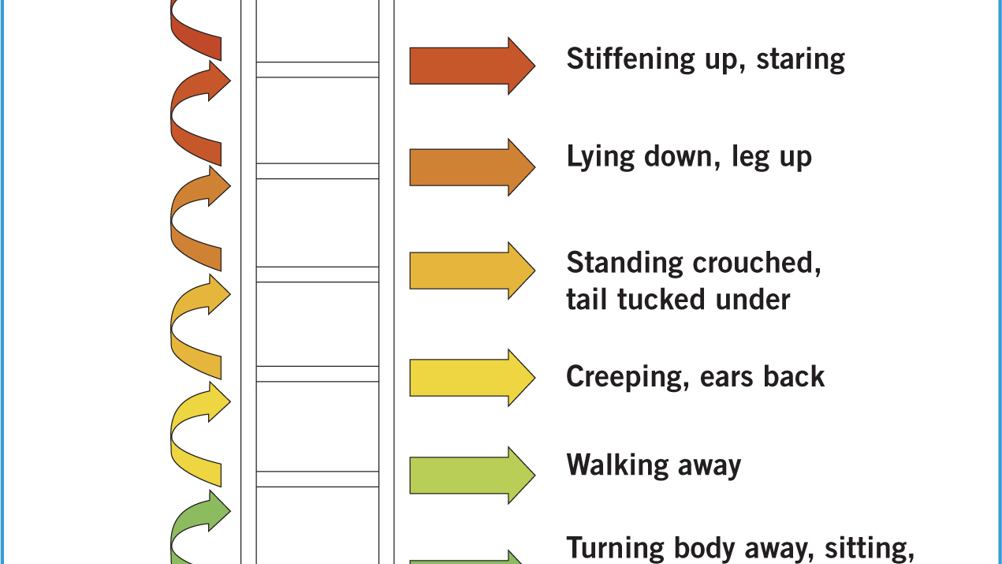

Despite the need for evidence-based advice regarding the behavioural health of their companion animals, owners may struggle to realise that this advice can be readily accessed from their veterinary practice. Many veterinary clients still rely, instead, on popular misconceptions perpetuated by the media and other pet owners. Furthering this problem is the reticence of some veterinary professionals to become involved in queries about patient behaviour, as they feel ill equipped to support the client and patient. This article forms part of a species-specific series of articles, intended to provide basic behavioural guidance that can be delivered by practice staff. This specific article focuses on enabling any veterinary practice to give basic support for the emotional and behavioural needs of their canine patients.

The Royal College of Veterinary Surgeon's Code of Professional Conduct for Veterinary Nurses (2017) requires both the health and welfare of veterinary patients to be maintained and the legal and ethical definition of welfare includes an animal's emotional and behavioural needs as well as its physical needs (Hedges, 2017). Although veterinary nursing courses are increasingly emphasising to students the importance of understanding the natural behavioural and environmental needs and the emotional complexity of patient species, practising nurses often find it difficult to source the necessary support, or sufficient time, to meet their patient's emotional and behavioural needs. A previous article introduced an argument for the introduction of first aid behavioural support for patients into practice routine. This article is intended to provide some practical solutions that will enable veterinary staff to offer preventative welfare and behavioural first aid advice to the owners of canine patients.

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting The Veterinary Nurse and reading some of our peer-reviewed content for veterinary professionals. To continue reading this article, please register today.