Anecdotally veterinary nurses are not being utilised to their full capacity in clinical practice. Veterinary nurses are trained and assessed for competency in admission and discharge of patients, pre-operative checks, using clinical equipment, and medical and surgical care, as per the New Zealand Qualifications Authority (n.d.). This list is not exhaustive but indicates the scope of tasks for which veterinary nurses are trained. In many clinics, however, veterinary nurses have reported that the veterinarian is completing these tasks instead of veterinary nurses.

Discussion of the role of the veterinary nurse, and the execution of specific tasks in practice is not a new issue. Molyneux (1998) listed the skills veterinary nurses in practice should be undertaking which included sample collection, processing and analysing, intravenous (IV) catheter placement, and urinary catheter placement. Following this, at a presentation at the 3rd AVA/NZVA Pan Pacific Veterinary Conference, veterinarian Dr Karen Koks (2010) talked about the under-utilisation of veterinary nurses in practice, and how to make better use of veterinary nurses. Her suggestions for utilising veterinary nurses better included organising practice areas into ‘zones’ whereby veterinary nurses would perform all the clinical tasks in that zone, except for diagnosis, surgery, and prescribing. This would include placing IV catheters, running blood tests, and monitoring anaesthetics. This topic was addressed in 2012 at the New Zealand Veterinary Nursing Association annual conference by veterinarian Dr Linda Sorensen (2012), who stated in her address that ‘the goal of the nurse-centred clinic is to fully utilise the nursing staff within legal limits’. Dr Sorensen stated that this requires a shift in perspective from veterinarians, who need to be willing to delegate clinical tasks to their veterinary nurses. Veterinary nurses also need to be willing to take on the added responsibilities.

In this study the incidence of regular tasks completed by veterinary nurses, and the expectations of their role in clinical practice according to veterinary nurses and veterinarians in New Zealand was measured.

Methods

A structured web-based survey was distributed to New Zealand Veterinary Nursing Association (NZVNA) members via email, in the New Zealand Veterinary Association (NZVA) e-newsletter, and on social media.

The survey consisted of 38 multi-choice questions and a comments section. The questionnaire was divided into four main sections. In Section One, respondents were asked to give their demographic information such as age, gender and ethnicity, level of qualification, place of employment, and level of income. In Section Two, respondents were asked about the tasks undertaken in veterinary practice on a regular basis. In Section Three respondents were asked about their ‘wellness’, in terms of stress and compassion fatigue they feel they experience in their work, and how they cope with stressors (paper in review). This led on to Section Four, asking about the respondents' current awareness of voluntary registration for veterinary nurses, and their NZVNA membership status. The questions were predominately multi-choice or matrix questions with numerous questions allowing for comments.

Results

Demographic analysis

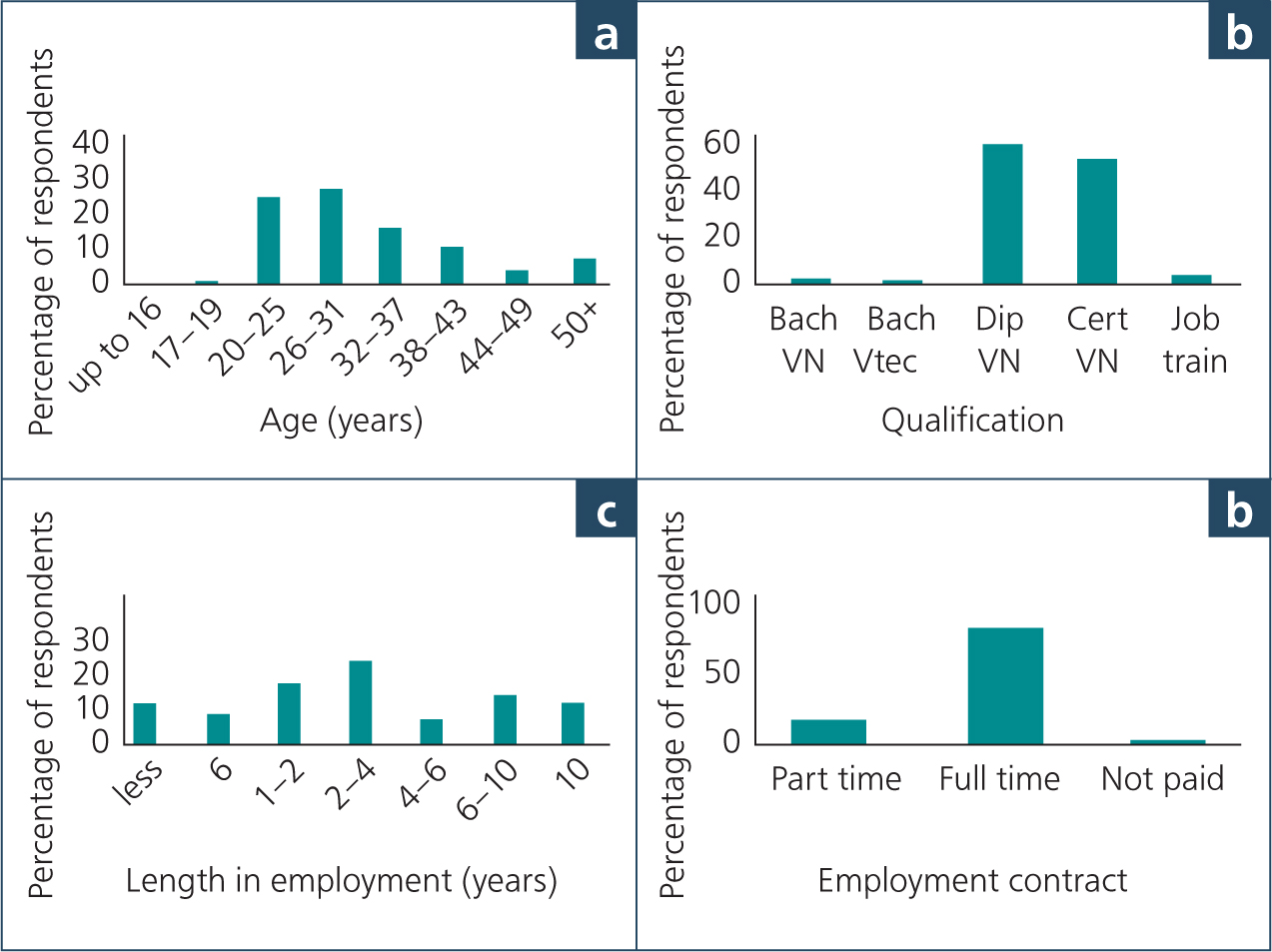

The survey was made available to 1479 veterinary nurses, with 288 surveys completed, representing 19% of the self-identified population of veterinary nurses. Female respondents represented 99% of respondents and most were aged between 20 and 31 years of age (Figure 1a). Of those, 52% (n = 129/247) reported having a minimum qualification at Diploma level (Figure 1b). Eighty-two percent (n=203/248) work full-time (25+ hours per week; (Figure 1c)), with 60% (n=151/248) having been in their current workplace for at least 2 years (Figure 1d).

Undertaking of clinical tasks — veterinary nurse responses

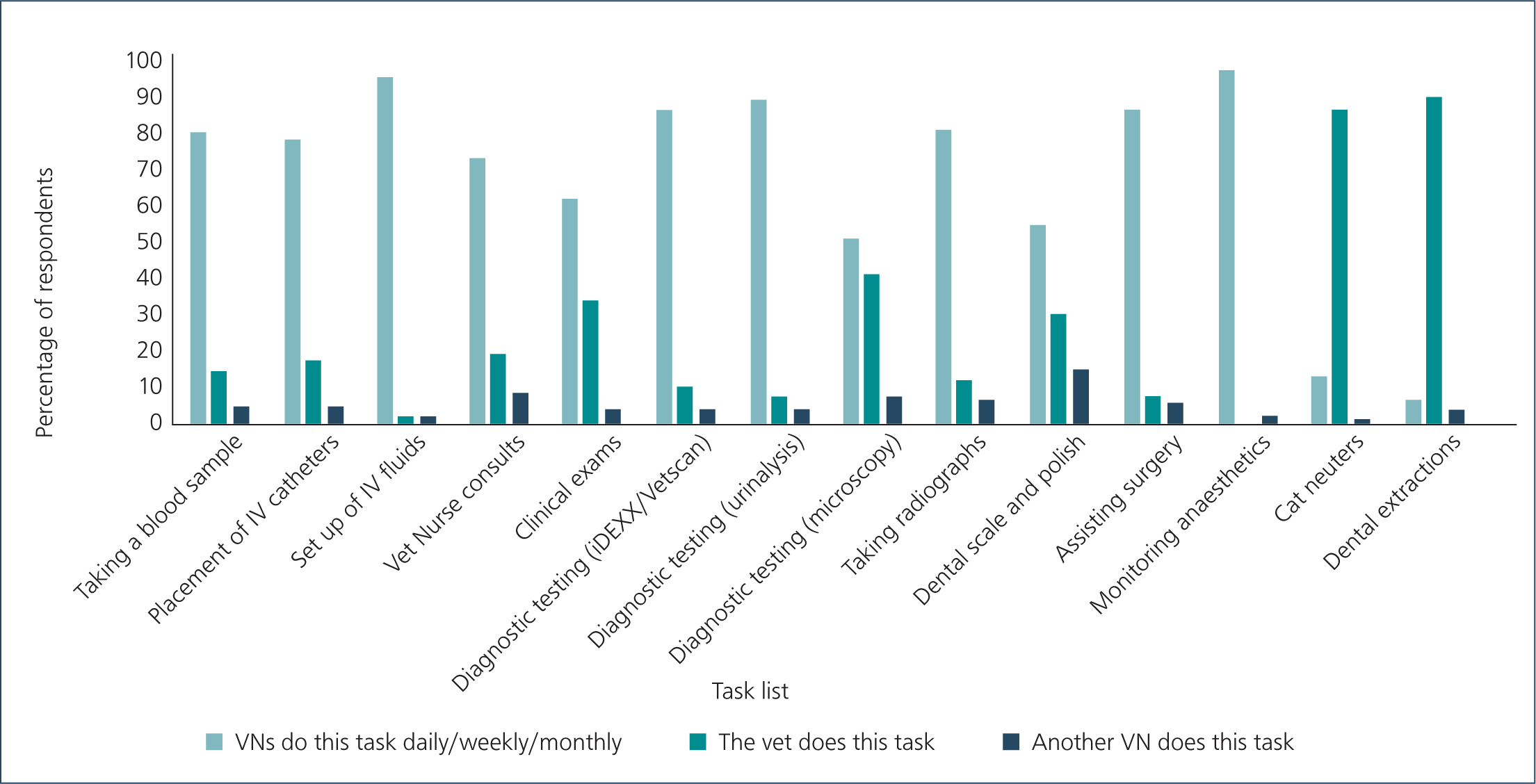

Survey respondents were provided with a list of clinical tasks veterinary nurses are routinely trained to perform as part of formal veterinary nursing education. At least 80% of the time, 7 of the 12 veterinary nursing tasks were reported to be completed by veterinary nurses (Figure 2). Two of the tasks (microscopy, and dental scale and polish) had a lower rate of completion by veterinary nurses, at 52% and 55% respectively. Cat neuters and dental extractions were performed by 13% and 6% of veterinary nurses with up to 40% reporting having had training (either formal or informal) in these tasks.

Undertaking of clinical tasks — veterinarian responses

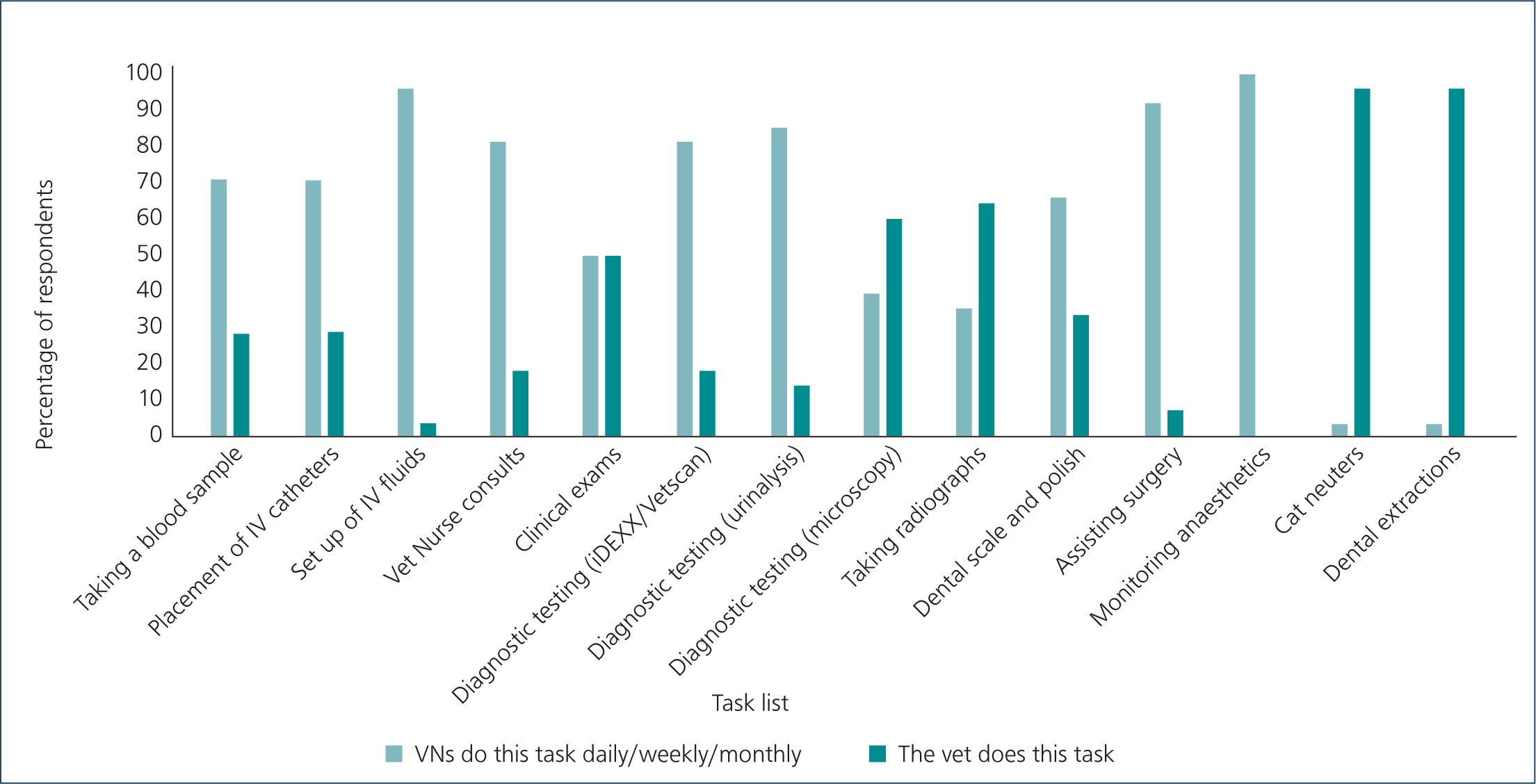

Many veterinary nursing tasks show a high level of veterinary nurse involvement and a low veterinarian involvement (Figure 3), e.g. setup of IV fluids is completed by a veterinary nurse was reported by 96% of nurses. Whereas others were undertaken by a similar percentage of veterinary nurses and veterinarians, e.g. clinical examinations are completed by 50% of veterinary nurses. Some veterinary nurse tasks show a higher level of veterinarian involvement (e.g. taking radiographs is reported by veterinarians to be undertaken by veterinary nurses 36% of the time, and veterinarians 64% of the time).

Perspectives on clinical task allocation

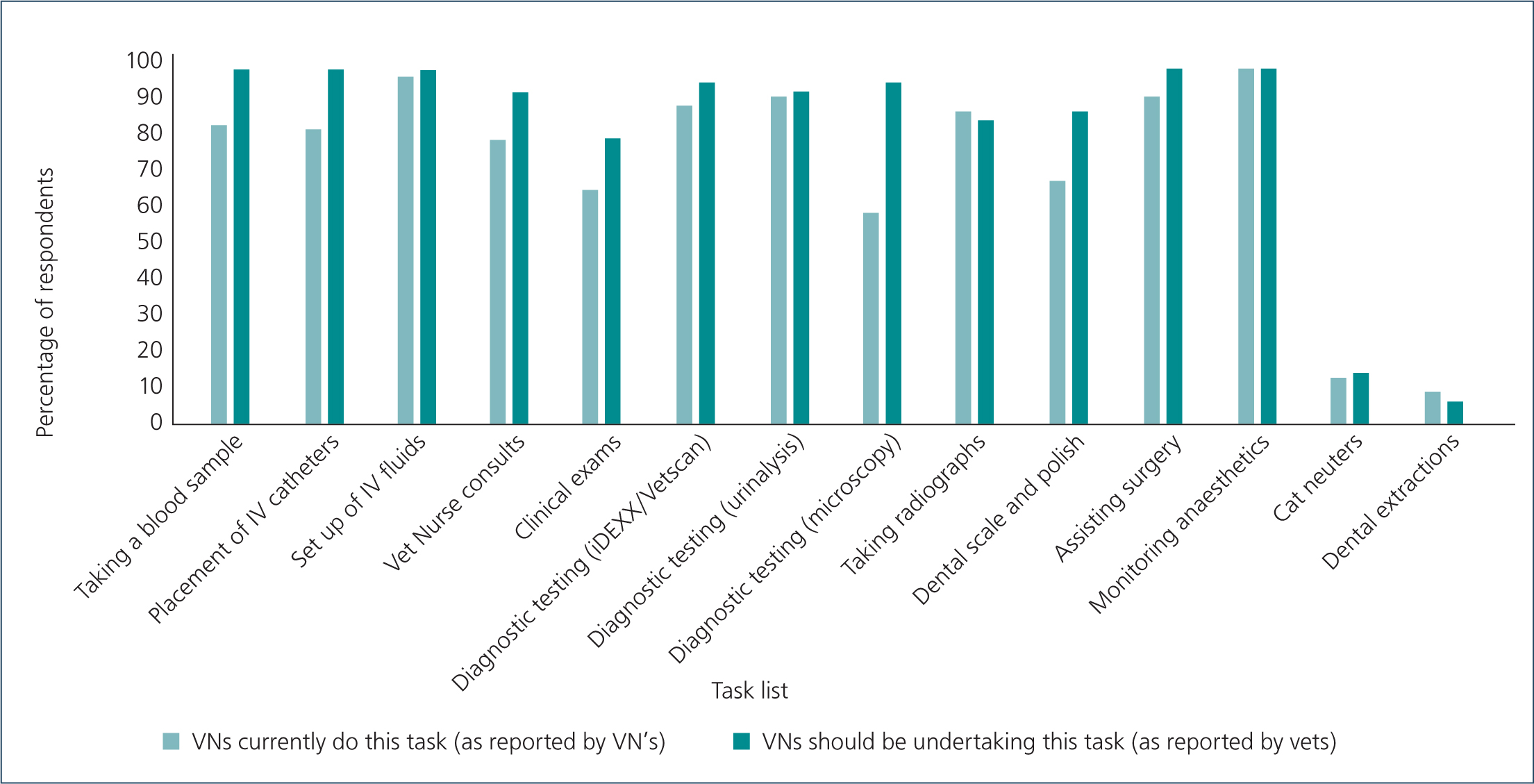

Veterinarians reported that veterinary nurses should be undertaking clinical tasks (Figure 4). Most veterinarians (> 90%) reported veterinary nurses should be undertaking tasks such as taking a blood sample, placement of IV catheters, and microscopy. For example, 100% of veterinarians reported that a veterinary nurse should place the IV catheters, but only 78% of veterinary nurses reported completing this task. Similarly, for diagnostic testing — microscopy, 96% of veterinarians reported that a veterinary nurse should be completing this task, but only 51.5% of veterinary nurses complete this task.

Discussion

The results of this survey support the importance of the issues reported by Molyneux (1998), Koks (2010), and Sorensen (2012): that is, veterinary nurses are capable of completing an array of patient care and surgical tasks and are willing to do this on a regular basis. In addition, the current survey indicated that veterinarians wanted veterinary nurses to complete more tasks in clinical practice, however, were not asked to suggest a reason for the current disparity between veterinary nurse and veterinarian tasks in clinical practice.

Theoretically, allowing veterinary nurses to perform their textbook role within a clinical setting improves wellbeing for veterinary nurses and veterinarians by enhancing job satisfaction and staff performance. This, in turn, increases retention and decreases issues such as compassion fatigue (Coates, 2016). From a business point of view, utilising veterinary nurses can increase profits by allowing the veterinarian to focus on their role rather than double handling tasks (Squance, 2014), or tying veterinarians up with clinical tasks they should be delegating (Sorensen, 2012).

A potential impact of increasing the tasks and responsibilities of veterinary nurses is that of stress, burnout and compassion fatigue (Chang et al, 2005). Negative mental health of both veterinarians and veterinary nurses needs to be a key factor in the planning and implementation of coordinating daily practice, and while it is likely that removing some tasks and responsibilities from veterinarians and handing this over to a veterinary nurse will decrease stress and burnout in veterinarians, it is also likely that this will simply shift this burden on to veterinary nurses. The mental health of the veterinary profession, and implications to this through changes in practice are an area of ongoing study both locally and internationally.

In 2017, the NZVNA implemented a voluntary register for veterinary nurses and technicians. Veterinarians have had mandatory registration since 1926 (Veterinary Surgeons Act, 1926). In 2017, 15% (216) of veterinary nurses had registered in 2017, jumping to 28% (422) in 2019 (New Zealand Veterinary Nursing Association, 2017, 2019a, 2019b).

Current guidelines regarding the limit to the tasks of a veterinary nurse in clinical practice is dictated by the Animal Welfare Act 1999 (Animal Welfare Act, 1999), and the impending amendment (Animal Welfare Amendment Act (No 2), 2015). For example, subgingival scaling is a key component of dental prophylaxis (Holmstrom et al, 2013), yet the new amendment has classified any procedure ‘below the gingival margin’, such as the veterinary nurse tasks of ‘scale and polish’, as being a surgical procedure only to be undertaken by a veterinarian or veterinary student. The Acts limit ‘significant surgical procedures’ to veterinarians and veterinary students, however, the 12 veterinary nursing tasks discussed are permitted through current legislation. Of interest (and potential concern) is the incidence of veterinary nurses reporting that they performed, but more likely assisted with, surgical procedures such as cat neuters and dental extractions in contradiction to the Animal Welfare Act. In addition, it is possible that the increase in responsibility of having veterinary nurses performing ‘veterinarian only’ tasks might increase general stress or compassion fatigue on veterinary nurses and potentially others employed in the same practice. Undertaking tasks outside a veterinary nurse's legal scope of practice may have potential repercussions to their ongoing clinical career should things go wrong (Brooke, 2011). It is apparent that clarity of role expectations within the various relevant legislation (and in the survey) is needed to identify clearly the role of the veterinary nurse in surgical procedures.

In the future, redistribution of this type of survey to veterinary nurses and veterinarians will allow us to investigate impact of registration on whether the increased accountability of registered veterinary nurses has had a positive effect, that is, a decrease in veterinarians performing veterinary nurse tasks.

Conclusions

Veterinary nurses are trained in tasks that they are not performing in clinical practice. The justification for this discrepancy is the subject of a future study with the aim of designing practical support for veterinary clinics to utilise the skills of veterinary nurses.