Canine leishmaniosis, caused by Leishmania infantum, is one of the most important vector-borne diseases of dogs in the Mediterranean basin (Baneth et al, 2008). It is also undoubtedly one of the most difficult of such diseases to identify and to manage. This is due to the variety of presentations and prolonged time before clinical disease in some cases, and because treatment does not always lead to a parasitological cure (Solano-Gallego et al, 2011). There is clear evidence that infected dogs have been introduced into the UK, even since before the start of the Pet Travel Scheme (PETS) as it was the one infection that could manifest after the quarantine period, and infected cases have continued since the start of PETS (Shaw et al, 2009). 403 cases of canine leishmaniosis were diagnosed in dogs in the UK between 1997 and 2012 (Fox, M. 2008, personal communication). There may be a lack of awareness in the UK for diagnosing and treating canine leishmaniosis and PETS does not afford any protection against the disease. With increasing numbers of dogs travelling abroad from the UK each year, this disease is becoming ever more relevant for the UK. The following information discusses some of the concerns that UK veterinary practices have in deciding how to deal with this disease.

Transmission

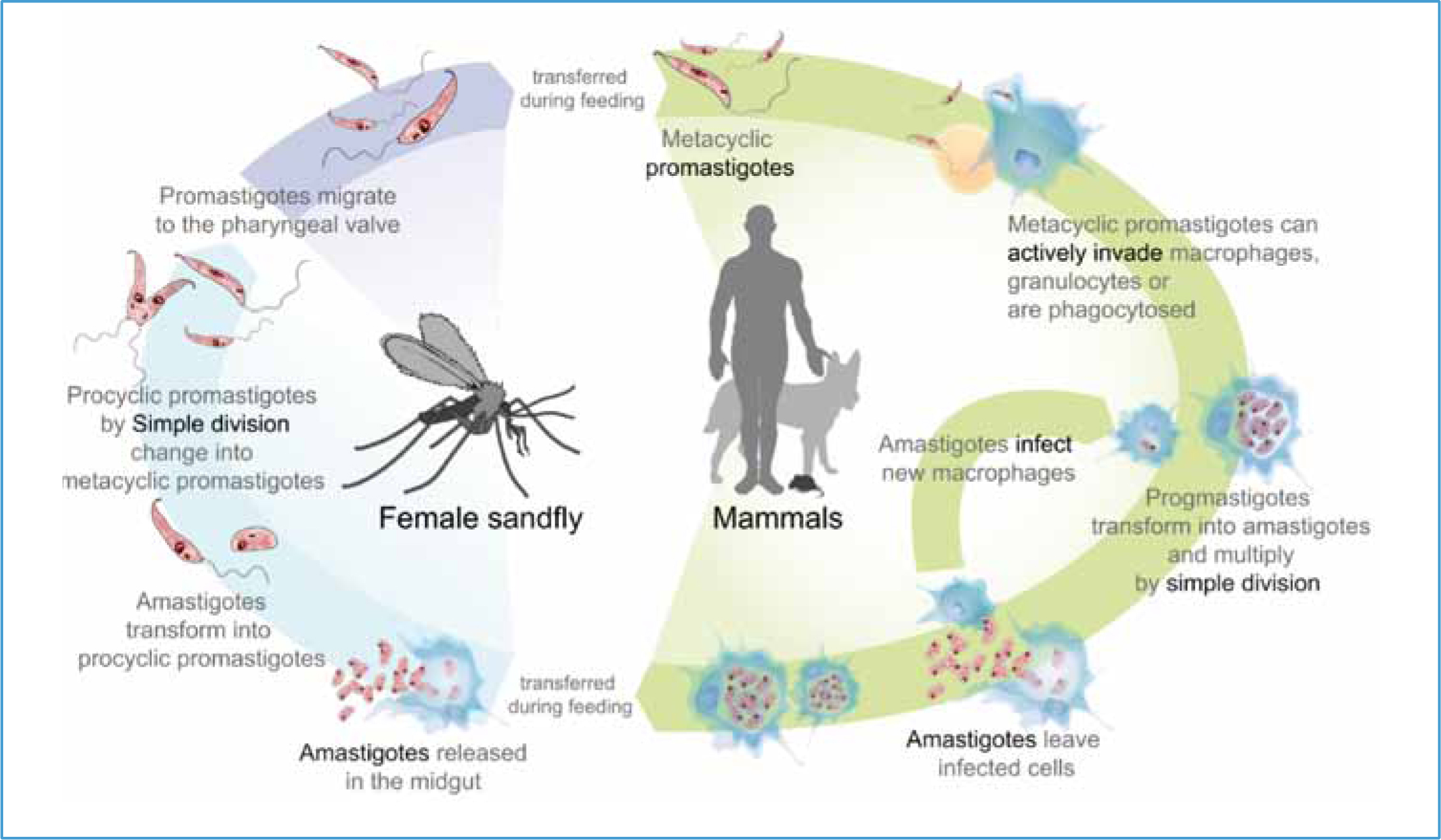

L. infantum is transmitted through the bite of the sandfly. The protozoa parasites are present in the superficial dermis of infected dogs, either within macrophages or free in the tissue. During a blood meal the sandfly takes up the parasites that ‘fall’ into the well of blood created by the insect's mouthparts. After approximately 6–12 days, the parasite replicates and becomes infective (subcutaneous metacyclic promastigote stage). This parasite stage migrates to the salivary glands of the sandfly and during a subsequent blood meal, promastigotes are released into the superficial dermis of the dog. These are then taken up by resident macrophages and can disseminate systemically, causing disease (Figure 1).

The skin, not peripheral blood, of infective dogs is the reservoir of parasites for the sandfly vector. Other biting and/or sucking arthropods appear not to be involved in transmission. Other transmission routes have been described, even though their importance in the epidemiology of infection is not always clear. Vertical transmission from infected bitch to puppies has been confirmed. Blood transfusion between foxhounds in the US has resulted in transmission of leishmaniosis, and sharing of needles has been hypothesised as another route of transmission, but only proven experimentally (Petersen, 2009).

The vector is not currently found in the UK and so transmission from infected dogs is unlikely at present. Effects of climate change could mean that sandflies might populate that UK in the future, with sandflies already established in southern Germany (Ready, 2010). Leishmaniosis is endemic through the Mediterranean region and the approximate northern edge of the area endemic for transmission is shown in Figure 2.

Clinical manifestation

Not all infected dogs will become ill. It is known that many dogs that are continuously exposed to the parasite in endemic areas remain asymptomatic (so called ‘resistant’ dogs) and this resistance to disease development is associated with a strong cell-mediated immune response. These resistant dogs are still infected with the parasite and may act as reservoir hosts.

When a dog becomes ill, symptoms can be very varied and include generalised enlargement of lymph nodes, scaly dermatitis, anaemia, anterior uveitis and renal dysfunction (Table 1) (Figure 3). Presenting signs may be associated with cutaneous changes which may initially be small areas of alopecia, or may be associated with systemic infection. The wide variety of presenting signs mean that it is impossible to define one or two pathognomic signs for clinicians to identify, other than the cutaneous lesions which may be present. A history of travel from endemic areas may assist in reaching a diagnosis and relevant questions should therefore be included in the history. A symptomatic leishmaniosis dog can transition to a resistant infected dog based on its current overall health status.

| Enlarged lymph nodes | Skin lesions, silvery crusting on the ears/face |

| Generalised hair loss | Conjunctivitis/uveitis |

| Lameness | Epistaxis |

| Anaemia | Kidney failure |

Diagnosis

In both endemic and non-endemic areas, clinically suspect dogs are tested by fine needle aspiration of lymph nodes and/or bone marrow in order to perform cytology and polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Blood PCR is not recommended as it lacks a certain degree of sensitivity as the organism is not reliably found in the blood. Indirect diagnosis through serology is also routinely carried out, but there are problems in interpreting results and antibody titres. This is because infection with Leishmania spp. is not synonymous with disease and asymptomatic dogs may present as seropositive despite not being considered ‘diseased’. As a rule, if the antibody titre for Leishmania spp. is four times higher than the usual laboratory cut off, the patient is considered positive and diseased. This reduces the over diagnosing of seropositive dogs. Sero-conversion (the period from infection to production of antibodies) can take several months following infection (Solano-Gallego et al, 2011). Samples can be sent to specialised laboratories including Acarus (www.langfordvets.co.uk/diagnostic-laboratories/diagnostic-laboratories/pcr-acarus/list-acarus-tests) and Testapet (www.testapet.com). While leishmaniosis remains a rare diagnosis in the UK, 403 cases have been diagnosed between 1997 and 2012 (Fox M, 2008, personal communication).

Treatment

The current recommended treatment protocol is a combination of the antimoniate N-metilglucamine (Glucantime®, Aventis; 100 mg/kg daily, subcutaneously) and allopurinol (Zyloric®, Aspen; 10 mg/kg daily, per os). The use of oral miltefosine (Milteforan®, Virbac) has been associated with a greater risk of disease recurrence, but can be an alternative when dogs/owners do not tolerate Glucantime® (Andrade et al, 2011). There are currently a lack of independent studies to confirm the efficacy of domperidone (Janssen Pharmaceutica): Leisguard®, ESTEVE, and other immune-modulating therapies. Follow-up to treatment should include evaluation of total protein and albumin to globulin (A:G) ratio, urine analysis (proteinuria) and antibody titres. Ideally, bone marrow PCR should be carried out twice at 6 month intervals to confirm parasitological cure. It is important that treated dogs are not under dosed as this may lead to treatment failure. This occurs in some parasite endemic areas in order to reduce treatment costs for the owner. Where treatments are not available in the UK they can be obtained from overseas with a special import licence (www.vmd.defra.gov.uk). While applications are processed quickly, there is obviously a delay between diagnosis and treatment where importation of medicines is necessary. Depending on the clinical presentation, ancillary care and nursing should be provided as appropriate.

Transmission prevention

A vaccine is available for sero-negative dogs that has been shown to be effective in protecting up to 68% of dogs from disease (but not from infection) (Oliva et al, 2014). Vaccinated dogs sero-convert over many months making it difficult to differentiate vaccinated dogs from naturally infected dogs. If vaccinated dogs are subsequently infected, they can have lower parasitaemia with less infectivity to sandflies (Oliva et al, 2014). Vaccination, together with other preventive measures such as remaining indoors from dusk to dawn and the use of insecticides and repellents, should be considered in situations where a dog is travelling to endemic areas. The downsides to vaccination are the cost and that vaccinated dogs are difficult to distinguish serologically from infected dogs as sero-conversion will occur in both situations. The latter may cause difficulties in interpretation of blood results in the event of subsequent investigation of disease.

In endemic areas, where dogs are at continued risk of infection through sandfly bites, routine application of effective repellents and, when possible, keeping dogs indoors during the night, are the two major recommendations for avoiding infection. All blood donor dogs must be screened for L. infantum antibodies and infected bitches should not be used for breeding (Solano-Gallego et al, 2011). These same precautions should be recommended for infected dogs in non-endemic areas, including the UK, if they have travelled to endemic areas. There is currently no convincing evidence that culling infected dogs is effective in reducing the prevalence of L. infantum infection in dogs or the zoonotic risk in endemic areas. In non-endemic areas, practitioners should evaluate each individual case, based on client compliance, patient response to treatment and follow-up evaluation before considering euthanasia as an option.

Owners planning to take their dog to endemic areas should obtain advice about preventing transmission prior to travelling. Advice should include the option of vaccination particularly if the animal will be resident in the endemic area for an extended period, together with other management strategies used by owners in endemic areas including the use of repellents and keeping dogs indoors from dusk to dawn (Table 2).

| Establish the travel plans for the pet hence know where client is travelling to (or from) |

| Sleep indoors in the evening when sand flies are active and feed |

| Use synthetic pyrethroid insecticide repellents |

| Consider pet vaccination based on a risk assessment of how long the pet will be in an endemic area |

Zoonotic risk

Humans are at risk of infection in endemic areas through the bites of sandflies. There appears no identified risk of transmission from infected dogs directly to humans. Immune competent individuals mount an effective cell-mediated immune response and do not develop disease. Young children and immune compromised adults may become ill and require treatment.

Conclusions

Canine leishmaniosis is a difficult disease to manage and therefore infection should be avoided where possible. Standard procedure at present is to diagnose, evaluate, treat and monitor the response to treatment. Euthanasia of an infected dog should not be considered until full evaluation is carried out and other options explored. The UK is not currently high risk for canine leishmaniosis as the vector is not yet present, however climate change poses a risk that this will change in the future and veterinary practices should be prepared. Regardless of whether L. infantum becomes endemic in the UK, increasing numbers of UK dogs are travelling to endemic areas and infection rates in the UK are likely to increase. It is important that veterinary professionals familiarise themselves with the clinical signs to aid detection, along with a number of other important exotic diseases.