Over recent years, the veterinary nursing profession has advanced. With changes to the clinical working environment, there is a renewed drive to provide the best quality care to patients, and an increase in the application of evidence-based medicine (EBM) and evidence-based veterinary medicine (EBVM). In this rapidly changing environment, it can be challenging to know if the care being provided is beneficial and whether it is in line with current EBM/EBVM. This is where, as veterinary nurses, we can put clinical governance to use to help us to plan, measure and improve current clinical practices (Health Quality and Safety Commissions (HQSC), 2017).

Clinical governance forms a comprehensive approach, which encompasses quality improvement (QI), EBVM and clinical audits, to help build reflective practice. It opens up the opportunity for productive discussion into how a practice can provide high-quality patient-driven care (HQSC, 2017). Clinical governance should allow for the transparent discussion of care between all members of the veterinary team; this process should help protect the patient by highlighting areas for improvement and allowing for the reporting of errors in a non-judgmental environment (Mosedale, 2019). By combining QI and EBM/EBVM, we should be able build precise and clear standards of care that are to be delivered to every patient, every time (HQSC, 2017).

Evidence-based medicine and evidence-based veterinary medicine

Before looking at the implementation of QI and the use of clinical audits, it is important that we understand what EBM/EBVM is. This way, we can optimise patient care and client interactions, with an understanding of how EBM/EBVM works with QI, allowing a comprehensive approach to clinical governance and best practice guidelines.

EBVM and EBM have been defined in numerous ways, but it is commonly referred to as a structured, clear and meticulous approach to decision-making used by experts in a clinical environment, that aims to incorporate clinical expertise and evidence sourced from external research (Arlt and Heuwieser, 2016).

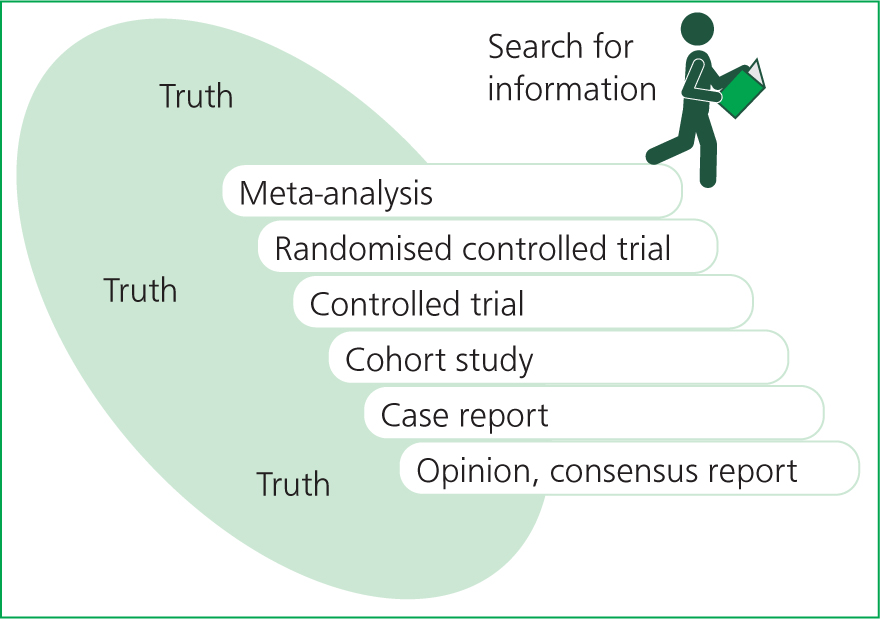

It is important that as veterinary nurses, we can take an evidence-based approach to our work in clinical practice; this includes sourcing and critically appraising bodies of evidence and research. One way we can do this is by using the ‘staircase of evidence’ approach when sourcing EBVM/EBM (Figure 1).

The basis of the ‘staircase’ method is to illustrate how evidence can be ranked from strongest to weakest. Other metaphors are also used to display this hierarchy of evidence, typically displayed as a pyramid with the strongest evidence at the tip of the pyramid and the weakest at the base. Arlt and Heuwieser (2016) published this alternative ‘staircase’ version, which proved in their study to provide a clearer representation of how the search for evidence should be carried out in comparison with pyramid metaphors.

The ‘staircase’ depicted in Figure 1 along with an image of a person reading represents how the search for evidence should start at the top and be worked down, with an awareness that with every downward step taken, the less reliable the evidence may become. We always aim to use the highest form of evidence available; this being metanalysis or systemic reviews, with opinion pieces and consensus reports at the bottom (Table 1) (Arlt and Heuwieser, 2016).

Table 1. Classes of evidence

| Class of evidence | Type of evidence | Description |

|---|---|---|

| I | Systematic review/meta-analysis | An amalgamation of evidence collated from all relevant randomised controlled trials |

| II | Randomised controlled trial | Experiments where study participants are randomised to a treatment or control group |

| III | Controlled trial without randomisation | Experiments where study participants are non-randomised to a treatment or control group |

| IV | Case-control/cohort study | Case-control study: comparisons of participants who suffer with a condition (case) with ones who do not suffer with a condition to determine characteristics and predictions about a conditionCohort study: observational study of a group/s (cohort) to monitor or determine the development of an outcome/s of diseases |

| V | Systematic review of qualitive or descriptive studies | An amalgamation of qualitive or descriptive studies that aims to answer a clinical question |

| VI | Qualitive or descriptive study | Qualitive study: collection of data on subjects or human behaviours to understand how and why decisions are madeDescriptive study: provides background information on the what, where, and when of the topic of interest |

| VII | Expert opinion or consensus | Authoritative opinion from an expert committee |

Types of clinical audits

Clinical audits are a large part of QI. They are used to help assess how similar clinical practice is to recommended practice or guidelines. Clinical audits are not a new development and have been used successfully across a wide range of specialties, such as the automotive, aviation and human healthcare industries (Evans, 2014). In the veterinary industry, QI is being used more frequently and practices are beginning to see the advantages that can be gained from conducting audits. One such advantage is the ability to highlight areas that may not be being carried out as successfully as initially believed.

Some of the main types of audits that can be applied in practice are process, outcome, structural or significant event audits (Mosedale, 2019). Each can be used to measure various practices, but all can help to create guidelines, protocols or checklists. Some examples of how to use these different audits are outlined in Table 2.

Table 2. Types of audit

| Audit type | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Process audits |

|

|

| Outcome audits |

|

|

| Structure audits |

|

|

| Significant event audits |

|

|

Conducting an audit

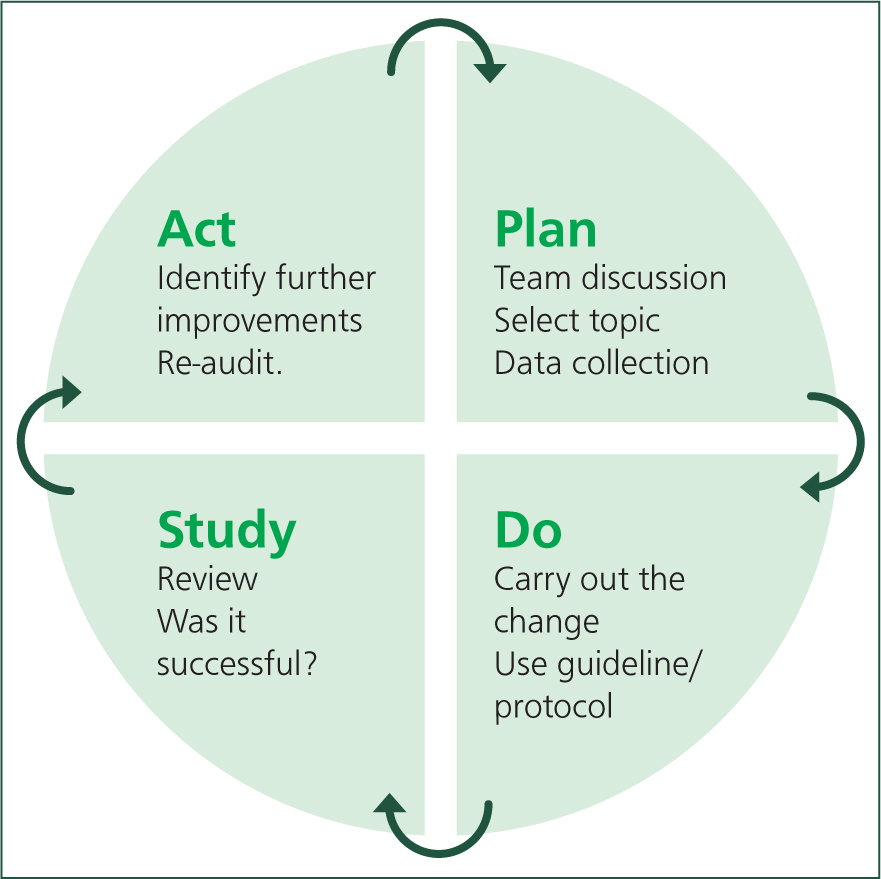

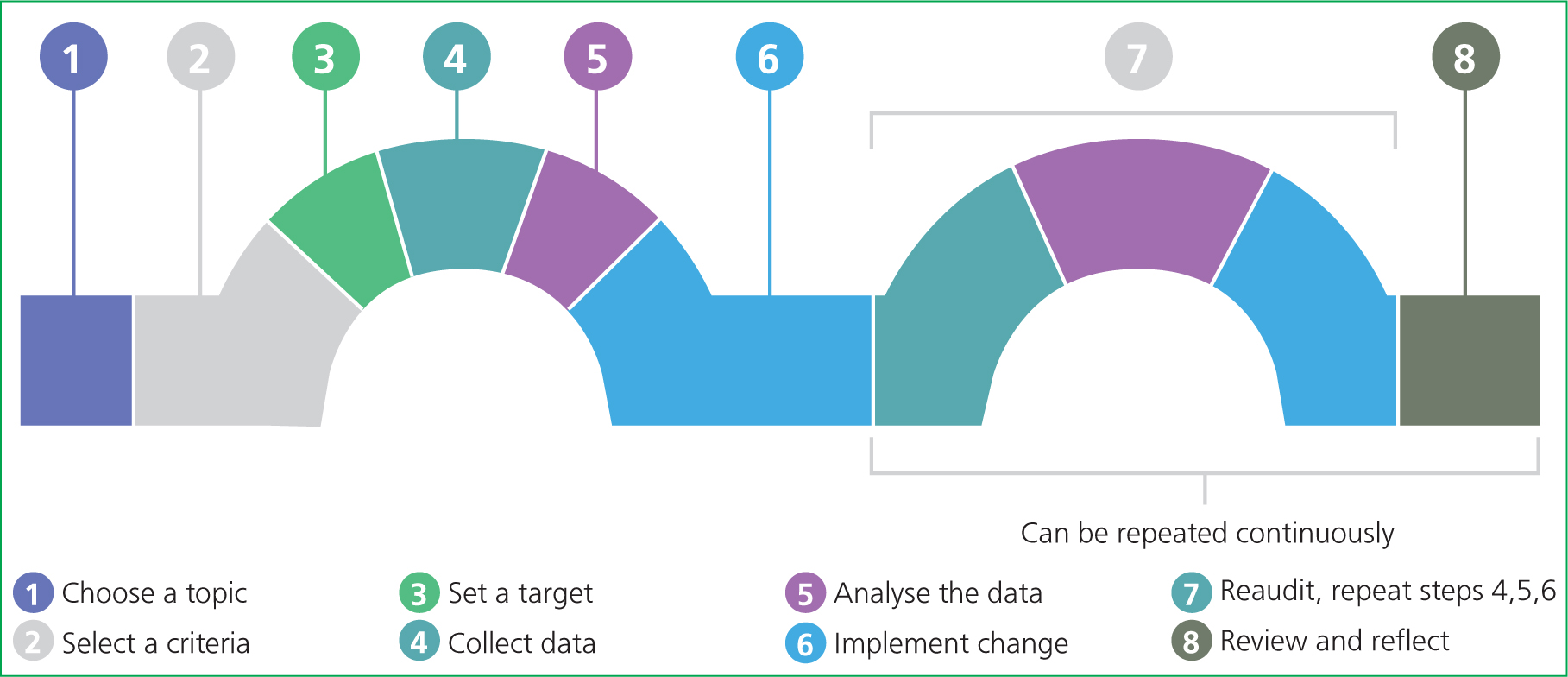

Typically, clinical audits occur in a cyclical process. In human healthcare, plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles have been used successfully (Figure 2). However, RCVS Knowledge (2019) provides a linear version of this cyclic process (Figure 3), which follows a similar pattern.

Planning

When beginning the auditing process, prior to looking at any data or numbers, it is important to involve the team members who may be affected by changes implemented from the audit. We work in a multidisciplinary environment so it may be necessary to involve more than just veterinary surgeons and nurses; for example, receptionists and support staff may also be impacted and, potentially, it may be necessary to look across specialties such as anaesthesia, theatre and emergency medicine teams (Mosedale, 2019). Team support is vital to the whole auditing process, without which it will be difficult to make changes where needed. Holding a team meeting can be a good place to start so ideas and concerns can be voiced. The topic selected needs to be relevant to the practice, measurable and carried out regularly enough to gain the most benefit from audit. It should also be an area that the team has voiced they feel needs improvement (Mosedale, 2019).

During the planning stage, a target or standard needs to be set. This is essential for ensuring a well-planned out audit, making the whole process easier and giving the team something to aim for (Mosedale, 2019). If possible, standards or targets can be set using EBVM. However, owing to a lack of available EBVM, this is not always possible. If this is the case, internal targets can be set using retrospective data. For example, the number of animals pain-scored over the last month could be looked at using this as a guide to set a target. It may be that only 50% of animals received a pain score before analgesia was administered, so a target of 80% could be set. A timeframe needs to be established within which to hit the set target; this will depend on the topic selected and the type of audit being used. An outcome audit may look at monthly neutering outcomes and a process audit measuring whether pain scores are used post-operatively on surgical patients could span approximately 1–2 months. Whatever way this is decided, time frames need to be sensible; initially measuring over a 6-month period may not be practical as people may forget or lose interest, and only looking at data from 1–2 weeks may not be representative of overall outcomes.

It is important to mention that when selecting an area to audit, the right questions must be raised. This should not be research; audits should not be used to compare treatment interventions, outcomes of novel treatments nor census work (Hexter, 2013). Audits should measure how closely best practice is followed rather than used to figure out what best practice is. When creating a guideline or protocol later in the audit process, best practice can be sought using EBVM research, pre-prepared guidelines or protocols from external sources (Hexter, 2013). Once again, taking pain scoring as an example, we would aim to audit whether or not a pain-scoring system is used before administration of analgesia — not which pain score provides the most accurate score in painful animals.

Data collection and analysis

Once an audit plan has been created and agreed on by the wider team, a smaller team of auditors can be tasked with data collection. How you collect data may depend on what you are auditing. It may be helpful to ask team members to complete a questionnaire to establish gaps in training. If using a questionnaire, keep it simple and allow for anonymity so people do not have to feel embarrassed if they are unsure of how a task should be performed. Also consider incentives or rewards to maximise participation. You may alternatively use self-reporting, which does come with some limitations as it relies on staff reporting after they have completed a task. If this method is used, make sure the reporting system is simple rather than time-consuming to use; this will ensure maximum uptake (Thakore, 2020). Retrospective data can be collected. This might involve using practice management computer systems or gathering and checking paperwork; for example, looking at neutering outcomes at postoperative checks or looking through paperwork at the process of dangerous drug-recording. Some practices have now moved to computerised patient records so knowledge of looking for data on these types of systems may be required (Thakore, 2020).

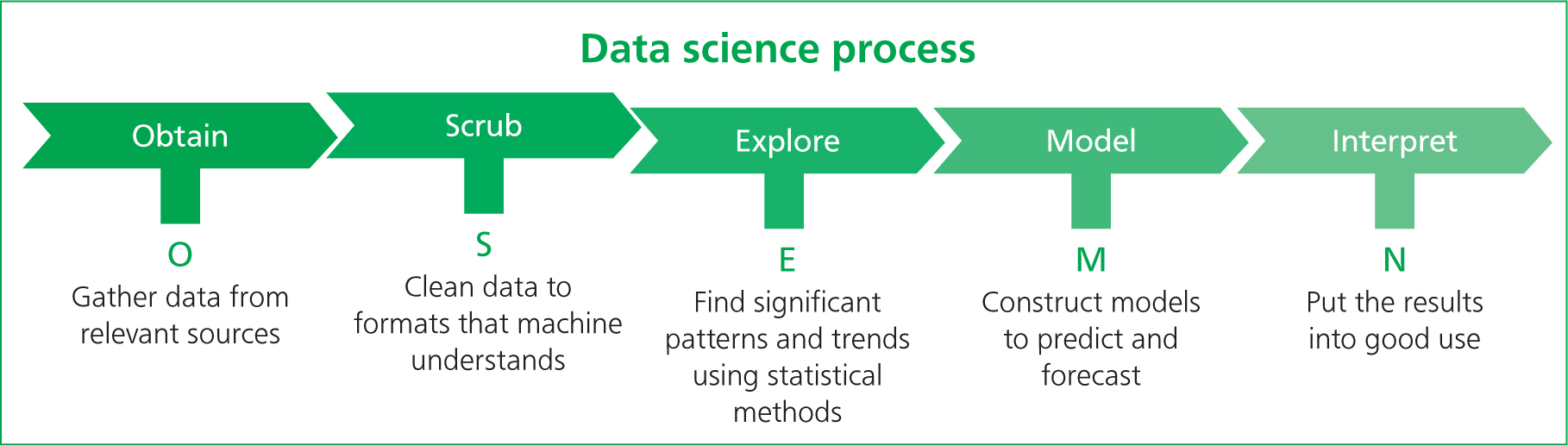

When approaching this part of the audit process, it may be useful to apply a scientific data collection and analysis model to ensure we are maintaining scientific integrity. The OSEMN framework (Figure 4) is simple and can be adapted to help in the clinical auditing process of collecting and analysing data (Lau, 2019).

The process is started by obtaining the data, which may be done in various ways: observations, interviews, questionnaires, group discussions or external sources (Lau, 2019). Once data are obtained, it can be ‘scrubbed’. This helps us to decide which data are relevant and which are not, aiming to make the analysis of the data collected relevant to our topic (Lau, 2019). This may involve the conversion of data into other formats such as using Excel spread-sheets to streamline and formalise the data (Lau, 2019). This can aid in the exploration of collected data, looking for correlation and trends within the data and testing the variable used. For example, you may find that patients that are pain-scored after surgery have an increased chance of being administered with top-up analgesia than when compared with those that have not received a pain score (Lau, 2019). This step uses the process of correlation. It is important to remember, however, that correlation between certain variables is not always an implication of causation. Therefore, during this step, remember to use some caution but also curiosity as means of identifying where some data may not be lining up as expected (Lau, 2019). Modelling the data may be slightly less relevant when being applied to clinical auditing. However, it can help us to predict future data sets, so we may find a correlation between pain-scoring and top-up analgesia given. This modelling phase can be used to predict that if we implement a system where every animal that has undergone surgery receives a pain score, then the number of animals receiving the appropriate top-up analgesic should increase (Lau, 2019). This then falls in line with the interpretation of the data; the predictive model and ‘scrubbed’ data can be used and presented to the wider team (Lau, 2019). The data need to be easily interpreted by all team members in a clear and transparent format — this allows for fully open discussion of the results between all members of the team (Lau, 2019).

Once the required data have been collated, the OSEMN framework can be applied. It may be helpful to use bench-marking; this takes the practice's data and compares it to a national database of standardised data or against data obtained from internal clinic structures, such as other branch practices. There are already some databases available through RCVS Knowledge (2019) that can provide benchmarks. Vet Audit provides a national audit for neutering complications, the canine cruciate repair registry and an antimicrobial resistance audit via the RCVS Knowledge (2020) website. These can be used to compare data once collected.

It is important to be transparent with these data and discuss them openly with the team. If targets were not met, begin a discussion as to why; for example (Mosedale, 2019):

- What barriers prevented people from meeting the set target?

- Is additional training required?

- Is there enough available equipment to carry out the task?

- Were staffing levels appropriate for the task to be completed?

- Were there time management issues?

Implementation and monitoring

During these discussions, an action plan should be made regarding how to overcome as many of the barriers to completing the task as possible. Once a plan has been created, this can be implemented as a set of standards, a protocol or a guideline (Mosedale, 2019). It may be worth putting memos out to any staff who could not be present at these meetings or having members of the audit team verbally tell any absent members how they plan to move forward, putting up poster reminders or implementing a checklist — all of these actions combined could help to remind staff of the new changes and improve compliance (Thakore, 2020).

We should also plan to re-audit. Time frames for re-auditing will most likely depend on the results from the initial audit. If benchmarks or targets were not met, a shorter time frame of 3–6 months may be appropriate. Once the protocol or guideline is established, re-auditing may be done bi-annually or annually — but again, this will depend on the topic being audited and the results.

Barriers to auditing

There can be quite a few barriers to auditing when it is initially suggested. Some may think that it is a way of monitoring how they do their job; others may not believe there are any issues with the current practice; and others may feel ambivalent towards change (Evans, 2014). A literature review carried out by Johnston et al (2000) looked at 93 published audits, which included a variety of clinicians' experiences and views of the auditing process. This review highlighted that some staff perceived the auditing process as a way of lessening clinical judgement and owner-ship, there was also discern over audits creating a hierarchy among more senior staff and/or management that could potentially lead clinicians to feel territorial or isolated professionally. However, despite these negative views, plenty of positive advantages were also highlighted such as improved communication between local and wider teams, improved patient care, increased professional satisfaction, and more effective administration (Johnston et al, 2000).

A lack of knowledge and curiosity of the scientific process and the methodologies behind conducting data collection, analysis and presentation can be a potential barrier to implementing clinical audits for veterinary nurses. It can be a daunting prospect to initiate QI within practice when prior training is not readily available to everyone. The use of a mentoring system could be a way to overcome this barrier. Clinical mentors are well established in most scientific communities and have been found to be an essential role in developing medical human professionals (National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM), 2019). Mentors can provide a working relationship that provides guidance, advice, experience and support within clinical practice, and are typically long-term roles, which can be beneficial for both the mentee and mentor (NASEM, 2019). It may be valuable before implementing clinical audits to seek out another veterinary nurse with experience in auditing or prior knowledge of the scientific process who can advise and guide during the initial implementation process.

Managing a team with differing personalities is a challenge but forcing people to change could potentially create a hostile and unpleasant working environment. There are suggestions that change can cause a grief-like reaction for some people so it may be that small changes initially will be more beneficial in the long term, allowing the team to ease into change and alteration to their working environment (Thakore, 2020). Managing all of this can be difficult, so it must be considered that everyone is motivated by different objectives. While some share a vision of future change, others may be fact- and figure-driven so until the initial audit is completed, they may take longer to get on board with the idea (University Hospital Bristol (UHB), 2017).

Being transparent with data and discussing it openly with the team can help. For instance, if there are not enough qualified nurses to complete the task, could a veterinary nursing assistant be trained to aid or complete the task and report to a qualified nurse? If the veterinary surgeons are time-limited in consultations, could an appointment be made in nurse consultations where the procedure can be carried out and results-reported to the veterinary surgeon prior their main consultation?

It may be that there is a lack of equipment, or that the available equipment is damaged. This can be rectified and, once an audit has been carried out, requests for certain equipment can be made. The initial audit can be used as proof that inadequate equipment is creating a barrier to meeting a target (Mosedale, 2019).

Trying to audit too much in one go can also become a barrier, as taking it all on at once can make the process difficult. QI should be about small incremental steps and not trying to leap from one point to the next (Evans, 2014). These small steps can help encourage the team to build collectively on ideas; specifically, regarding what obstructs and encourages individuals when making changes to the current working system (Evans, 2014). There may be simple solutions to some issues and, after the initial audit, reservations will start to ease or disappear. Physical evidence can be useful to prove that there are problems or that development is required (UHB, 2017). However, some barriers — such as staffing levels — may not be so simple to overcome.

Conclusion

The future of veterinary nursing is changing and with a drive for a more evidence-based approach, how we can alter our stance in practice and provide every patient with the same standards of care needs to be considered. The implementation of QI, clinical auditing and mentoring systems could be a route towards changing how we perform in our roles; from referral to primary care nurse settings, every-one has something to gain. The QI processes are well established in human healthcare and other industries; as the profession advances, the application and benefits that can be found across the veterinary sector must be considered.

The use of fellow veterinary nurses as mentors within the profession would be a step forward as we become advocates of the scientific process, creating clinical curiosity and a movement towards more evidence-based nursing practices. This approach will only be of benefit, both to current and future registered veterinary nurses, and to the animals under our care.

KEY POINTS

- Clinical audits are a part of quality improvement, which aim to improve current protocols and guidelines and compare care provision against pre-set standards and benchmarks.

- Clinical audits are not research; when auditing, the focus is on how a procedure is being carried out, not what ‘best practice’ is.

- When initially undertaking clinical audits, there may be barriers such as staff concerns, lack of equipment, insufficient time and inadequate planning.

- Full team involvement and clarity during the process can help to improve auditing outcomes and aid in the successful implementation of changes to protocols and guidelines.

- Clinical audit can be used to shape and create guidelines, protocols and checklists.

- The use of peer mentors can build on veterinary nurses' involvement within the veterinary scientific community.