The VN Futures scheme set up by the British Veterinary Nursing Association (BVNA) and the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (RCVS) has identified several issues in veterinary nursing today. These are organised into themes affecting the profession, which have produced a number of ambitions for the future (VN Futures Action Group 2016):

- Creating a sustainable workforce

- Structured and rewarding career paths

- Confident, resilient, healthy and well-supported workforce

- Proactive role in One Health

- Maximising nurses' potential

- Clarified and bolstered veterinary nurse's (VN) role via a reformed Schedule III.

The VN Futures working groups are aiming to address these. You may have seen the issue being referred to as the three ‘Rs’, as the below are the initial factors that were raised as issues in veterinary nursing:

- Recruitment

- Returning to work

- Retention.

However, the ambitions appear to show a hidden theme relating to the identified issues. In many senses, veterinary nurses are not a visible profession to clients, to veterinary colleagues and, sometimes, even to each other in the veterinary nursing community. The areas in which veterinary nurses lack an identity are apparent in terms of choice of uniforms, the lack of representation in financial aspects of the veterinary practice, and in their visibility, or lack thereof, in the media.

Veterinary nursing uniforms do not always differentiate them from other staff, so visually they can become lost. This can be seen anecdotally through a search of Google images. The move towards coloured scrubs to identify staff is advantageous in terms of comfort and gender neutrality of uniforms, but needs to be advertised to clients and staff alike to promote the different roles. This is rarely done in the veterinary world, when compared with human care; but it is essential to promoting the veterinary nurse's role (Davidson, 2016). While many veterinary nurses are attached to the traditional colour of green for their uniforms, is it still relevant today, and does a single colour achieve the aim of making veterinary nurses visible?

Veterinary nurses also lack a recognisable media image, and their roles are hard to capture on the numerous veterinary TV shows. This is owing in large part to historic portrayals of medical staff on fictional TV series, which continue to influence TV shows created today.

Financially, the veterinary nursing role is lost as skills are rarely allocated to registered veterinary nurses (RVNs) on veterinary invoices. In the author's experience, this is widespread, and has been supported in the response to Davidson and Marsh (2017). Therefore, the client does not see where the veterinary nurse has contributed to their pet's care. Instead, a veterinarian's name appears beside every skill listed, hiding the veterinary nurse's input. The income they generate is rarely apportioned to either individual veterinary nurses, or the veterinary nursing team.

Why is this an issue? A lack of visibility means that veterinary nurses risk not being recognised by employers, clients, and even the rest of the veterinary nursing community. This lack of visibility leads to a lack of recognition for our work that impacts the entire industry.

In the first of two parts, this article will consider the issues surrounding the veterinary nurse's image, through what they wear and how nurses are perceived in the media.

History of the nurse and veterinary nurse image

The traditional nurse image is of a human nurse, wearing a starched dress with a white cap and sleeve cuffs. This image is still used to identify nurses today, as can be seen from the call button displayed in Figure 1 from an NHS hospital in 2016.

This is no longer a relevant image, and is not representative of the veterinary nurses' NHS counterparts. However, its continued use means that human nurses also struggle with their identity such that their roles are not easily identifiable by what they wear. Perhaps promoton of the veterinary nurse role through uniform identification should look towards the NHS model, where posters are being used to depict the uniforms and roles to patients, visitors and staff.

Is green the only colour?

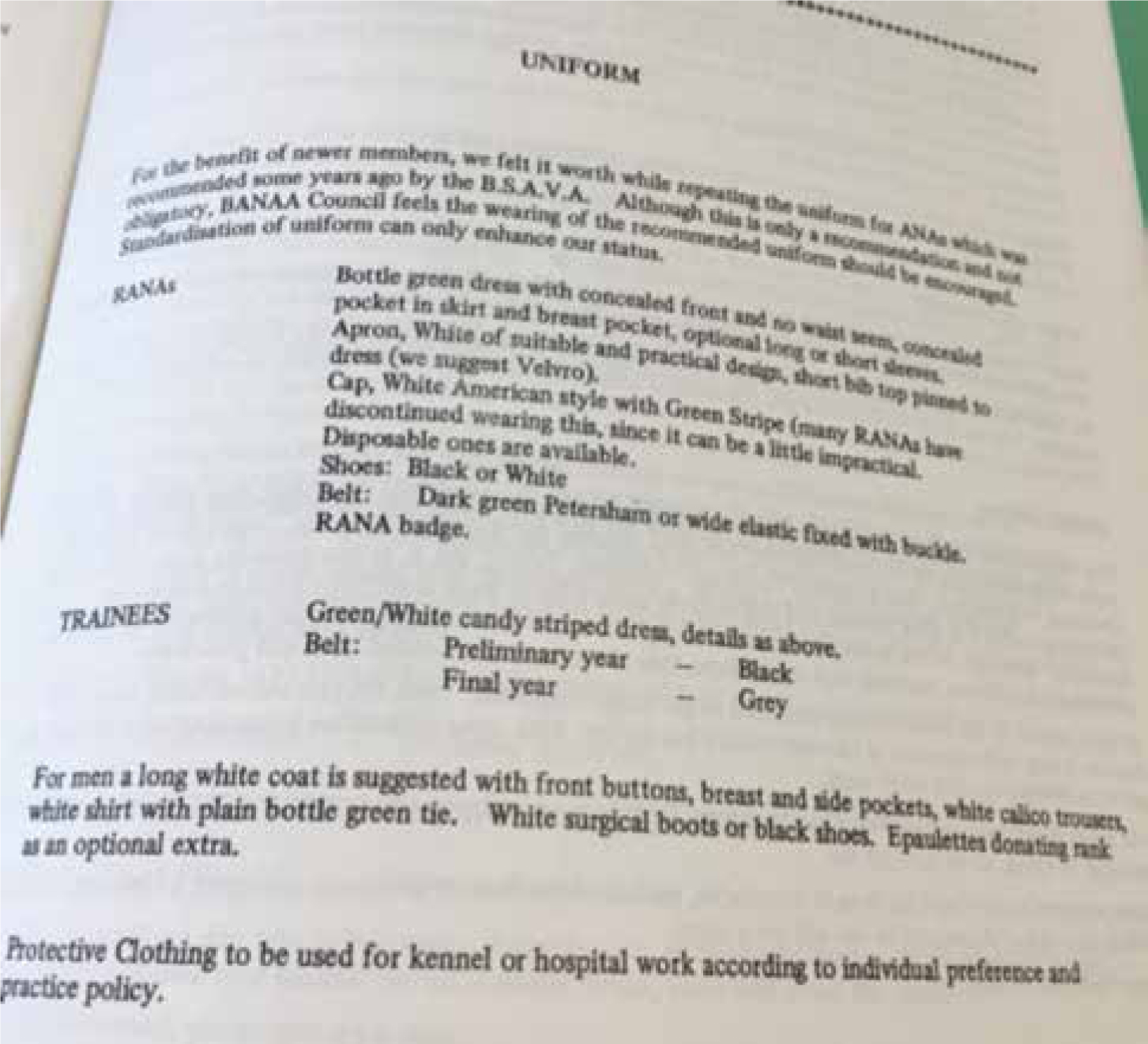

The history of the traditional veterinary nursing ‘greens’, and the bottle green colour favoured for their uniforms, comes from a decision taken by the British Small Animal Veterinary Association (BSAVA) at some point in the 1960s (Figure 2). The BSAVA Congress in 1969 had the first nursing presence from the British Animal Nursing Auxiliaries Association (BANAA), the forerunner of the BVNA (1986).

While the BVNA did not enforce the uniform colours, it did recommend them (Davidson, 2017). Research for this article has suggested that the colour was chosen because frogs are green and RANA is Latin for frog (anecdotal), or that the green chosen reflects the colour of drapes in theatre (Davidson 2017; Figure 3).

Further research is required to establish the origin of the colour choice from the BSAVA. As part of an overview on the image of veterinary nurses, it would be prudent to understand how the industry has arrived at the current situation. Only some use the green colour and dress style uniforms — and they are not obligatory, and their impact on promoting the image of veterinary nurses is not fully known. However, it would appear to be limited if articles such as these, discussing the lack of accessible veterinary nursing image, need to be written.

The preference for a single colour to promote the varied role of a veterinary nurse seems rather limiting. Research for this article, as well as previously identified blogs, online searches, and anecdotal evidence from veterinary practices, have confirmed the presence of a need for uniforms that are suitable for the multiple roles veterinary nurses perform in practice. A single colour does not cover the role of a uniform to serve as an identifier of the wearer, as Wocial (2014a) states:

‘A uniform serves as a mechanism by which the public identifies the role of the wearer.’

If a veterinary nurse was required to wear one colour of uniform for the whole of their career, would that in itself not lead to confusion about their role and expertise? An appropriate uniform is key to veterinary nurses being visible to clients and the public.

‘Uniforms also can function within an organisation to create group identity’ (Wocial, 2014b).

This would confirm that the choosing of uniforms for the needs of each veterinary practice or group of practices is appropriate, and that advertising your chosen colour scheme is the best way to promote veterinary nursing via uniforms (Davidson, 2016). This would reflect the current NHS model where individual hospitals or entire primary care trusts can choose their own uniform colours, and then use posters to share identification of staff (Davidson, 2016).

How can veterinary nurses contribute to promoting an easily identifiable, strong and positive image of the RVN's professional role via what they wear? This includes what they wear, how they wear it and how they act.

The progress of uniforms into practical items to wear has created a visually homogenous veterinary care team, and it is noted in the human field that the same has happened:

‘We all wear scrubs and when we enter a room the family really doesn't know what area [we're] coming from’ (Lehna et al, 1999).

As veterinary nurses are carrying out separate roles from other staff, they do need to define who they are, for clients and staff alike. Many clients assume that only veterinarians wear scrub-style uniforms, as this is an image often portrayed via the media — again linked to historic portrayals of medical staff.

‘What a person wears sets the stage for further interaction and projects a professional image’ (Lehna et al, 1999).

Veterinary nurses should bear this in mind when deciding on a uniform policy for styles, colours and uniform presentation. Appropriate care and presentation of their uniform is as important as the colour and style.

Veterinary nurses also need to be aware that by prescribing to wear a recognisable veterinary nurse uniform, they are expected to meet the ‘group norms’ of the prescribed attire (Lehna et al, 1999). This raises the question, what are the group norms of qualified veterinary nurses? As the role progresses, with research and the production of academic articles, they are establishing a body of work that sets out the expected professional standards of a veterinary nurse. Post-qualification skills are also being established via the VN Futures programme. Joseph and Alex (1972) confirm that:

‘The uniform is a device to resolve certain dilemmas of complex organisations — namely, to define their boundaries, to assure that members will conform to their goals.’

Perhaps it is time to acknowledge that the veterinary practice today is a ‘complex organisation’, where adhering to a single colour or style to represent the veterinary nurse role is no longer practical. The working life of a veterinary nurse today would be almost unrecognisable to the veterinary nurse of the 1960s, which was the era in which the decision was made to suggest a single colour as the role's main identifier. The visual identifier needs to progress as the role has progressed.

Beyond colour

In looking at what components of nurse attire indicate professionalism, Lehna et al (1999) has identified research which has shown that it is not only the presence of a uniform that dictates who looks professional. Patients in the human field in the USA demonstrated that a clean and well-presented uniform was an important part of a positive image. Accessories also counted, and it was noted that the presence of both a stethoscope and the nurse's badge contributed to the overall impression of professionalism. This would suggest that veterinary nurses should be making the effort to wear their RCVS badges wherever possible.

Where veterinary nurses are relying on the visibilty of their role coming from the traditional green colour uniform, they need to consider whether they dilute the power of their medical uniform by wearing it in non-clinical settings? There are Department of Health (2007) guidelines that support changing into uniform at work and wearing it only in clinical settings—covering up if there is a need to go on a house visit or travel in uniform. The NHS guidelines have noted that the main concern about uniforms being worn outside of a clinical setting is public perception of hygiene and professionalism (Department of Health, 2007). If veterinary nurses are to improve the respect for their profession, is making sure they wear their uniform appropriately not part of this?

The way veterinary nurses conduct themselves is also key to promoting their professional status and professionalism. What they say and how they say it is as important as how they look. A positive interaction with a veterinary nurse will promote that they are caring, responsible professionals. If clients hear them being rude about patients or other clients, this has a negative impact on their image — both within and outside of the work place.

It would appear that there are more factors which contribute to creating a recognisable nurse uniform than colour alone. Cleanliness, accessories, context and conduct, are all key to promoting the veterinary nurse role.

If colour is important, then communicating the colour worn for individual roles is important in practice. A poster to show the colours that staff wear can help to raise client awareness of the different roles there are in their veterinary practice (Davidson, 2016). This would appear to be one way to raise more awareness of the veterinary nurse's status via their uniform, versus prescribing to one colour or style.

The professional status of nursing often is subjected to both internal and external debate. Wynd (2003) states that in the 1990s, it is acknowledged that the ‘establishment of a scientific foundation for the discipline of nursing advanced slowly and ongoing disagreements among nurses about educational requirements also contributed to difficulties in defining nursing as a profession.’

This has had an impact on the image of veterinary nursing. While discussions were taking place to ensure that the basis of the human profession was sound, the image portrayed by nursing uniforms was stuck in the traditional, female-centric image. This was compounded by the move towards showing the medical industry on TV, and the role that doctors played in promoting their own role. This is particularly apparent in terms of the advent of medical TV shows in the USA.

The media image of nursing

The media and its portrayal of veterinary nurses, as well as its power in shaping the public's view of the veterinary nurse, cannot be overlooked. There is evidence of a set formula for the portrayal of the human medical professions on TV in the USA, which is still used today (Turow 2012). It would seem that this has influenced the public's view of veterinary nurses.

It would appear that the roles of human nurses were overlooked when the template of 1950s USA TV shows was moulded by the American Medical Association (AMA) — a doctors-only organisation. According to Turow (2012), there was an AMA advisory committee of ten male doctors to advise on scripts for TV shows. There was no equivalent for nurses, perhaps because the nursing profession was still establishing its education path and overall role (Wynd, 2003). The advisory committee had two main goals for the TV image of doctors:

- Preserve the doctor's role as teacher of responsible behaviour

- Preserve the ‘godlike’ image of the physician as unquestioned ruler of the health-care setting.

This left space only for nurses as ‘ancillary and ill-defined helpers’ of the doctors (Turow 2012). This template for medical TV shows has altered little in recent years. TV medical programmes now show the personal lives of staff, and the struggle with work–life balance, but the nurse's role is still secondary to the doctor's (Turow, 2012).

This has led to ‘nursing invisibility’ (Trepanier and Gooch, 2014), where nurses are not contributing to patient care on screen, and they became messengers for the doctors. The tasks that are usually undertaken by a nurse are often then done by a doctor for the TV cameras, including high-impact tasks such as defibrillation (Trepanier and Gooch, 2014) — thus confirming the nurse's role as that of a secondary hand maiden to the doctors.

Could this ‘visual loss’ (Stanek et al, 2015) be part of a hidden curriculum that results in fewer viewers recognising and identifying with the role of the veterinary nurse?

If their uniforms do not mark them as separate professionals in the veterinary team, are the actions shown on TV noted as nursing tasks? When watching veterinary TV shows, it can be hard to differentiate between veterinarians and nurses. Perhaps others in the industry could differentiate, but members of the public may not be able to. While the RCVS Schedule III survey will be out in early October 2017, the industry is discussing what tasks RVNs are, and should be, doing. Do they also need to look at how the industry advertises these skills to the public so that the role is appreciated? Would the public know to look for veterinary nurses:

- Placing an IV

- Taking blood

- Monitoring anaesthesia

- Carrying out minor surgical procedures?

These are traditionally seen as veterinarian roles on TV. When there are anaesthesia or emergency situations on veterinary TV shows, does the public know that it is more likely to be an RVN wearing the stethoscope and monitoring the anaesthetic? An RVN giving IV medication? As these are portrayed as doctor roles in human TV shows, it is unlikely that viewers will recognise that it is a veterinary nurse doing these roles on veterinary TV shows.

This creates part of the ‘hidden curriculum’ — the part of learning that is not expressly taught for students or the public (almost like subliminal messages about the person or profession). The hidden curriculum appears elsewhere in the nurse's depiction on TV. Stanek et al (2015) note that the hidden curriculum shows themes of the portrayal of nursing:

- Hierarchy: nurses rarely shown doing own roles

- Work–life balance: nurses have to demonstrate total commitment to the role via unpaid overtime and sacrificing personal life for the role

- Role modelling: negative and positive of the nurse's role.

The hidden curriculum is also evident in education; it is:

‘more or less, the collective messages that students unknowingly pick up from the faculty and administration’ (Larkin, 2017).

The Royal Veterinary College (RVC) has been looking at its hidden curriculum. While this is diferent at every educational provider, the RVC found an interesting shift in students. Students were asked to rank attributes of professionalism:

‘Some attributes valued highly in the first year, such as social justice and altruism, were ranked low by the fourth year and replaced by professional autonomy and professional dominance, which both ranked highest’ (Stephen May in Larkin, 2017).

This is of interest as professional dominance could be interpreted as dominance over the rest of the veterinary team, showing that before graduation, student veterinarians are already working in the hierarchy, where veterinarians are dominant over veterinary nurses. This may reduce the team-building ability of new veterinarians, as well as encourage the subordination and invisibility of the veterinary nurse role. As veterinary nurses support so many veterinarians during extramural studies, it would be hoped that these relationships would be stronger than the hidden curriculum.

It is apparent that the hidden curriculum from education and TV greatly influences veterinary nurses' working lives. When in stressful situations, we go to what is familiar. The hidden curriculum is so familiar to veterinary colleagues and the public, people often do not even realise it exists. This is true for both staff and clients. When faced with a pet having treatment, owners' minds may go to the images they know from TV shows. These often consist of an older male veterinarian leading a team of females, whose roles are not clearly identifiable.

Conclusion

It would appear that veterinary nurses need to review how the veterinary nursing role is seen by their colleagues, and by those who see them in the media. Is sticking to a single colour for a veterinary nursing uniform helpful in promoting the role? Would an approach involving communication of the role, and help identifying veterinary nurses in individual practices, be more successful than an industry-wide adherence to a tradition that no longer reflects the veterinary nursing role?

Veterinary nurses should also be aware of how they present themselves, as cleanliness, accessories and attitude are as important as choice of clothing. Focus should shift away from a single colour across the industry, and towards individual practices and employers working with their teams to devise uniform policies which reflect the appropriate image. This would include:

- Colours that are role appropriate

- Clean and damage-free uniforms

- Accessories limited to those which are needed for the role

- RCVS badge worn where appropriate

- Clear difference between uniforms for different roles

- Method to show clients what chosen uniforms mean, e.g. posters, blogs, website

- Appropriate presentation and hygiene

- Personal conduct when interacting with clients and colleagues (Finkleman and Kenner, 2014).

Employers should also consider the presentation of staff on websites, social media and TV/radio/press.

The current TV image of the veterinary world will be hard to change; but if every RVN takes a stand within their own role to educate the public, this can be translated back onto TV screens, and people's minds.

Veterinary nurses are present and key figures in the veterinary industry; but in many ways, they are hidden as their image does not portray their skill sets. It is more difficult to recruit to a role that is hard to visualise; therefore, the pool from which prospective students are drawn will remain within its traditional demographic. Part two of this article will discuss further the issues of being hidden financially, and the impact this has on retention, as well as the ability to return to work.

KEY POINTS

- The VN Futures ambitions appear to have shown a uniting but hidden theme of the invisibility of veterinary nurses.

- The traditional green coloured uniform may not be identifying the veterinary nurse role clearly.

- Practices can choose their own uniform identifiers and share this information with clients via posters or social media posts.

- The promotion of nursing roles in the media are held back by the original template of 1950s human medicine TV shows.

- These issues combined mean it can be hard for clients to identify who is the veterinary nurse in a veterinary team.

- Each veterinary nurse can take responsibility for promoting their role in practice by presenting themselves well and working with their practice to advertise the role with posters and social media posts explaining uniform identifiers.

CPD Reflection Questions.

- 1. Review 3 photos from your practice website/social media and write down what are the identifiers for veterinary surgeons, veterinary nurses and other staff that can be seen in that photo. Include uniform, badges, name badges, accessories, actions or activities. NB — as you know the staff it may help to get someone who does not know them/does not work in a veterinary practice to help you — it will only take a few minutes!

- 2. Using the list made from No. 1 do you think these identifiers are clear for clients? How could you help clients recognise staff from uniform alone?

- 3. Make a list of common nursing tasks and equipment used. Watch an episode of a veterinary TV show that you do not usually watch — it could be from the UK or overseas. How many times do you see a veterinary surgeon do the tasks listed and how any times do you see a nurse do them? Keep count and compare totals at the end.

- 4. Once you have completed these short tasks consider No. 1 again and see if your website or social media photos could improve its representation of the veterinary nurse role.