The wild European hedgehog (Erinaceus europaeus) is a nonterritorial nocturnal species of mammal with a flexible diet consisting of a wide range of invertebrates, as well as small vertebrates and carrion. It is a frequent visitor to domestic gardens looking for shelter and food. As a result, injured and debilitated animals are often found by the public and brought into veterinary surgeries for treatment and rehabilitation. Hedgehogs carry a variety of parasites and burdens are likely to be high in already diseased patients. These parasites may contribute to on-going disease syndromes or cause clinical parasitoses in their own right. Some also have limited zoonotic potential. Veterinary nurses need to be able to help the veterinary surgeon diagnose parasitic infections in hedgehog patients and assess their significance

Parasites carried by hedgehogs can be broadly categorised into endo and ectoparasites.

Ectoparasites

Hedgehogs may be infected by mites, fleas and ticks.

Mites

A number of different species of mite may cause mange in hedgehogs. There have been relatively few studies establishing prevalence of these parasites in the UK, but a study in 2001 found prevalence of clinical mange in hedgehogs brought into clinic to be 6% (Bunnell, 2001).

- Capariniatic mange — Caparinia tripilis is a typical psoroptid mite with short tarsal hooks but body spines are absent. They have short mouthparts and feed on skin and epidermal debris. Adult mites are just visible to the naked eye and are often active. Infestations are often well tolerated but dermatitis with scaling, crusting, alopecia and quill loss may be observed, especially in the presence of concurrent disease or in immune compromised individuals. Crusting often occurs around the eyes and ears and affected animals will be prone to secondary bacterial infections and myiasis.

- Demodectic mange — although Demodex erinacei infestations are common in hedgehogs, clinical cases are uncommon and infection appears to be well tolerated.

- Sarcoptic mange — hedgehogs may be infested with Sarcoptes scabiei or less commonly Notoedric spp. leading to sarcoptic mange with associated crusting, alopecia, otitis, quill loss and pruritus. Infestations in hedgehogs, like sarcoptic mange in other species, have some zoonotic potential for transient infection and possibly more persistent infections in the immune suppressed.

- Otodectes cyanotis — ear mites can affect hedgehogs and cross contamination with cats is likely with the parasite able to survive for up to 12 days away from the host. Although some infestations in hedgehogs are subclinical, infections causing otitis are common. Less commonly infection can occur around the perineum causing mange.

With the exception of O. cyanotis and Notoedric cati, all hedgehog mite infestations are relatively host specific, but the mites have the potential to survive for days off the host and some can cause limited skin irritation in humans. Barrier hygiene and thorough disinfection of hospitalisation facilities therefore, must be performed if hedgehogs with mange are to be hospitalised. Diagnosis of mite infections can be achieved by direct visualisation of the parasite in the case of C. tripilis or O. cyanotis or by deep multiple skin scrapes. Treatment of infection with ivermectin by spot on solution or subcutaneous injection at 0.2 mg/kg every 14 days for 6 weeks is effective at eliminating most mite infestations. Topical ceruminolytic ear preparations may also be useful in clearing heavy infestations of O. cyanotis, but these are not as useful in hedgehogs as cats and dogs because of their smaller ear canals.

Fleas

Most flea infestations on hedgehogs are the host specific hedgehog flea Archaeopsylla erinaceid and are generally well tolerated by the host. They are also potential hosts for Ctenocephalides spp., Nosopsyllus fasciatus and Pulex irritans that may also infest other species. Heavy flea infestations parasitising sick casualty hedgehogs have the potential to debilitate the patient further and, with the exception of A. erinacei, establish breeding populations in the practice. Hospitalised hedgehogs should not be treated for fleas unless visible burdens are present. Pyrethrum powder and nitenpyram have been used successfully if treatment is required (Beck et al, 2005). Permethrin should be avoided. A sample of fleas should be examined under the microscope to see if species are present that may lead to persistent infestation in the practice and require environmental treatment. A number of flea identification articles and keys are available (Wright, 2018). Hedgehogs infested with Pulex irritans have zoonotic potential but in the UK this flea is very rare.

Ticks

Hedgehogs are common hosts for Ixodes hexagonus and Ixodes ricinus ticks and may be parasitised by both nymph and adult forms. These can be removed manually using a tick removal device and often general anaesthetic is required to achieve this comprehensively. Although hedgehogs may act as a reservoir for tick-borne pathogens including Borrelia burgdorferi, there are no reports of tick-borne disease in UK hedgehogs. Hedgehogs pose no direct zoonotic tick-borne pathogen transmission risk but it is important to remember that unfed ticks may fall off hedgehogs and then attach to people or pets in the practice. Nymphs are only 1–2 mm long (Figure 1) and can easily be missed. As a result gloves and gowns should be worn while removing ticks and then immediately disposed of. The surface used for the procedure should be thoroughly cleaned afterwards.

Endoparasites

A wide range of endoparasites parasitise UK hedgehogs including helminths (roundworm, lungworm and fluke) and protozoa.

Protozoa

Isospora erinaceid, Isospora rastegaievae and Eimeria spp. commonly parasitise hedgehogs, with one study finding 76% of UK hedgehogs infected (Whiting, 2012). They are species specific with most cases being subclinical, although heavy burdens can cause clinical disease. Clinical signs include weight loss, diarrhoea and haematochezia. Diagnosis is by detection of oocysts by direct faecal smear or sugar faecal flotation and can be treated with a 7-day course of sulphonamides. Environmental hygiene with licensed coccidiacidal disinfectants is essential to prevent numbers building up in the environment and leading to reinfection, especially if groups of hedgehogs are being rehabilitated together.

Nematodes

Nematode infections are very common in hedgehogs with a recent study finding 80% of UK hedgehogs sampled to be infected (Whiting, 2012). The most common are Capillaria spp. (threadworms, prevalence of 56% and 66% in studies) and Crenosoma striatum (lungworm, prevalence 23% and 71% in studies) (Gaglio et al, 2010; Whiting, 2012).

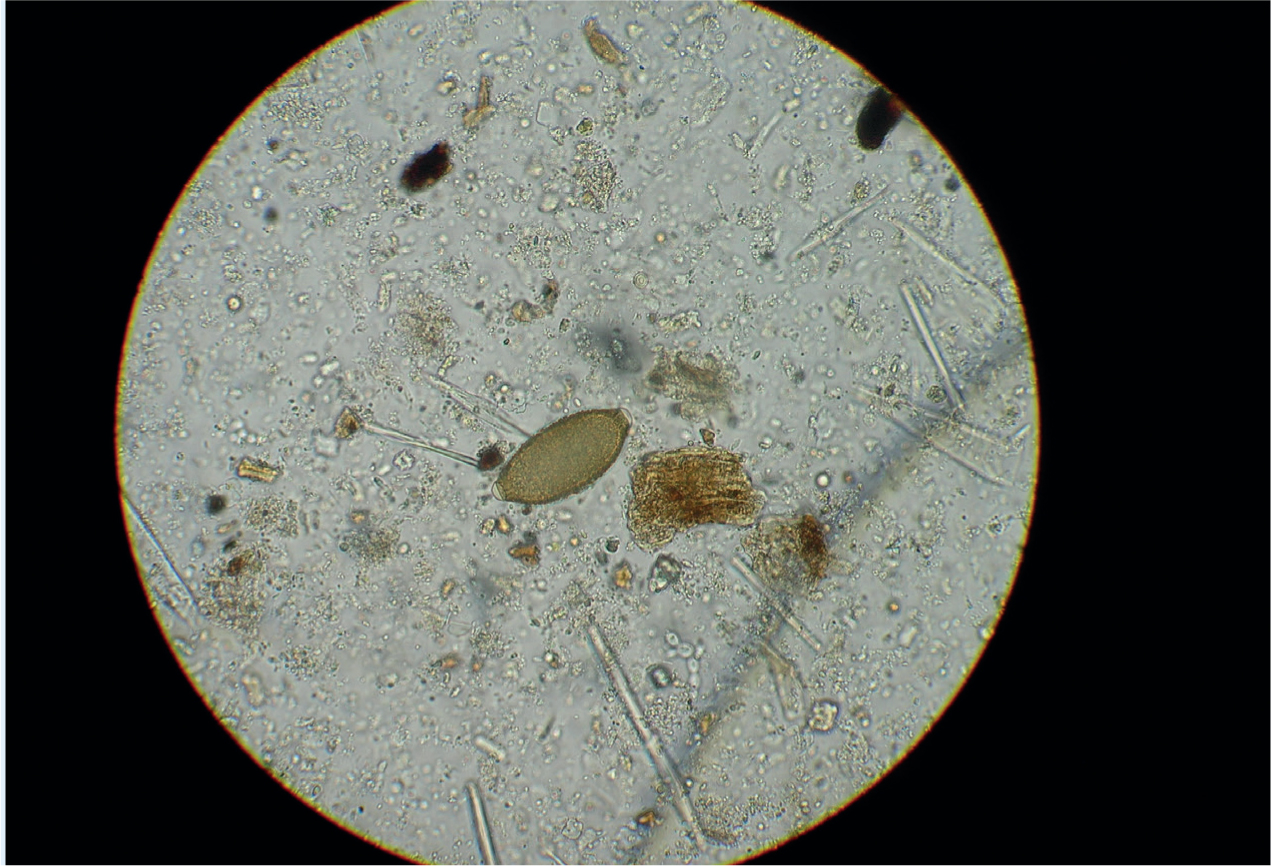

Capillaria ovoreticulata and Capillaria erinacei are intestinal roundworms of hedgehogs. The adults are 10 mm long hair-like worms and are often found incidentally at postmortem examination. Bipolar eggs are passed in the faeces (Figure 2) and can be detected through faecal flotation, but can be difficult to distinguish from Capillaria aerophila eggs. Mixed infections often occur, and this must be considered when respiratory and intestinal signs are present. Transmission can be direct through the ingestion of eggs once they mature to the larvated stage or through the ingestion of earthworms that may act as paratenic hosts. Infections are often subclinical, but in juveniles or in animals with concurrent disease burdens may become sufficient to cause diarrhoea and weight loss. Treatment is with fenbendazole at 100 mg/kg orally daily for 7 days or by weekly ivermectin injection. The possibility of direct transmission creates the possibility of transmission to other hospitalised hedgehogs so good environmental hygiene is essential.

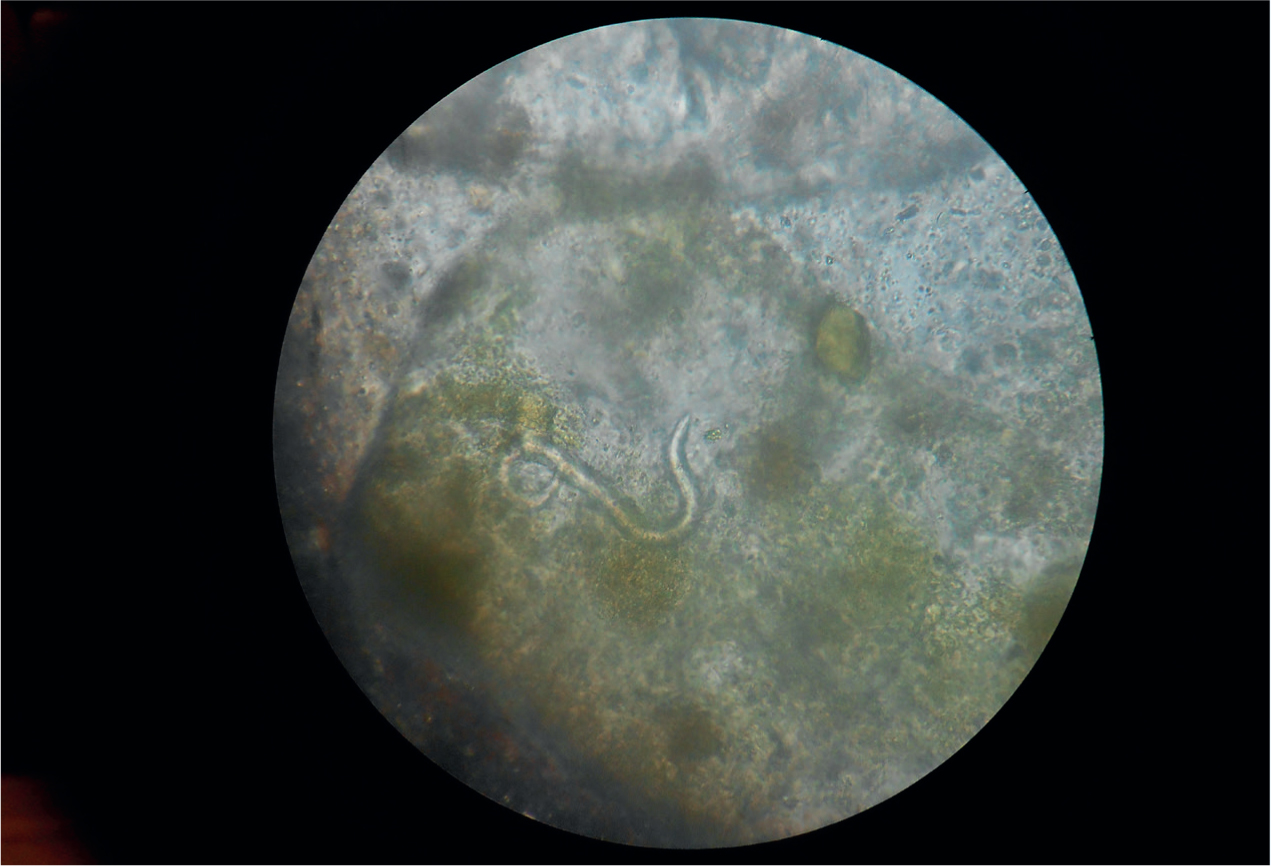

C. aerophila and Crenesoma striatum are lungworms of hedgehogs. C. aerophila shed bipolar eggs in the faeces (Figure 2) and may be seen in faecal flotation. C. striatum L1 larvae are also passed in the faeces and are approximately 300 µm in length (Figure 3). Detection of the larvae can be achieved by the Baermann flotation technique, but shedding of the larvae is intermittent and testing should take place over 3 consecutive days. Larvae can also sometimes be detected in a direct faecal smear. Most cases are subclinical or mild in healthy animals carrying low worm burdens with no clinical signs or rhinotracheitis. In hedgehogs, however, with concurrent disease or those approaching hibernation, morbidity can be very high, approaching 100% in some outbreaks. The high morbidity is associated with high levels of infection and as worm burden increases it is common to see broncho pneumonia with associated dyspnoea, weight loss, lethargy, ataxia and sometimes death. The prognosis for severe cases is poor. Levamisole 27 mg/kg is an effective treatment by subcutaneous injection for 3 days. Adverse reactions are sometimes seen however with hyperaesthesia, hyper salivation, hyper excitability, and dyspnoea so patients should be monitored for 30 minutes following administration, and supplemental oxygen and steroid administered if required. Patients that cannot tolerate levamisole can be treated with fenbendazole at 100 mg/kg orally for 7 days or weekly ivermectin. Severe cases will also need supportive treatment such as steroid, antibiotics for secondary infection, bronchodilators and supplementary oxygen. C. striatum requires arthropod intermediate hosts for transmission and so poses no risk of cross transmission in practice. Although C. aerophila can be transmitted directly it relies heavily on earthworm predation in hedgehogs to facilitate transmission as paratenic hosts and as such poses a low risk of transmission in practice. Basic barrier hygiene should still be implemented in infected animals as a precaution.

Trematodes

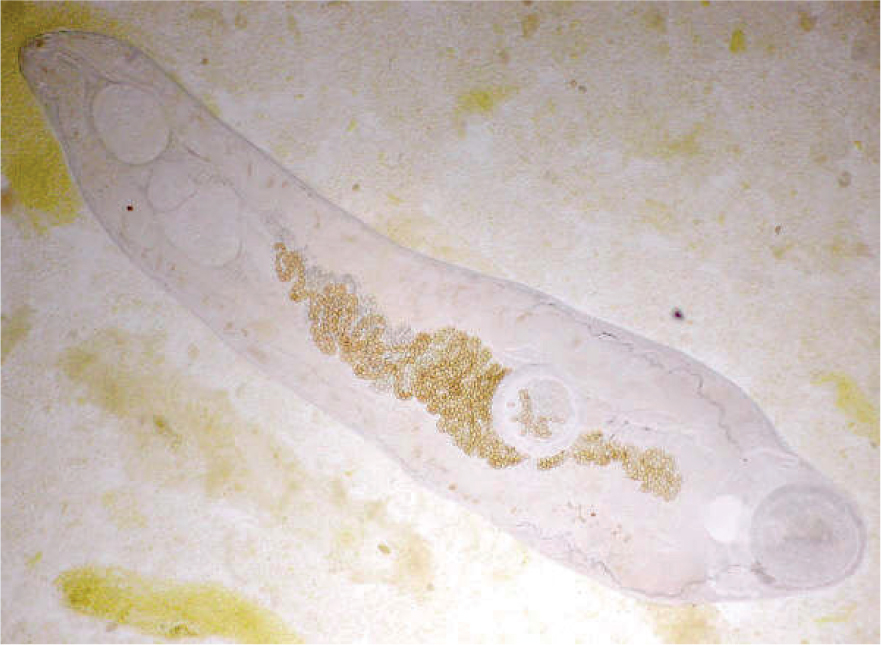

Intestinal flukes such as Brachylaemus erinacei frequently infect UK hedgehogs with prevalences of 23 and 55% having been found in studies (Gaglio et al, 2010; Whiting, 2012). Adult flukes inhabit the intestine and bile ducts, are 5–10 mm long and lancet shaped (Figure 4). Clinical signs of B. erinacei include weight loss in the face of increased appetite, restlessness and haemorrhagic diarrhoea. Severe cases can lead to progressive haemor-rhagic enteritis and inflammation of the bile ducts, anaemia and death. Diagnosis can be achieved by identification of trematode eggs in faeces, but like other trematode eggs do not float well in zinc or sugar flotation methods and sedimentation techniques are required. The eggs are operculate and contain a miracidium but are much smaller than many other trematode eggs (30 by 20 µm). Treatment is with praziquantel at 25 mg/kg orally every 48 hours until resolution of clinical signs or emodepside spot-on weekly. Supportive treatment is often also required for diarrhoea and liver function with antibiotics for secondary infection. In long standing or severe clinical cases, the prognosis is poor. The need for an arthropod intermediate host means there is no risk of transmission in the practice setting.

Acanthocephalids

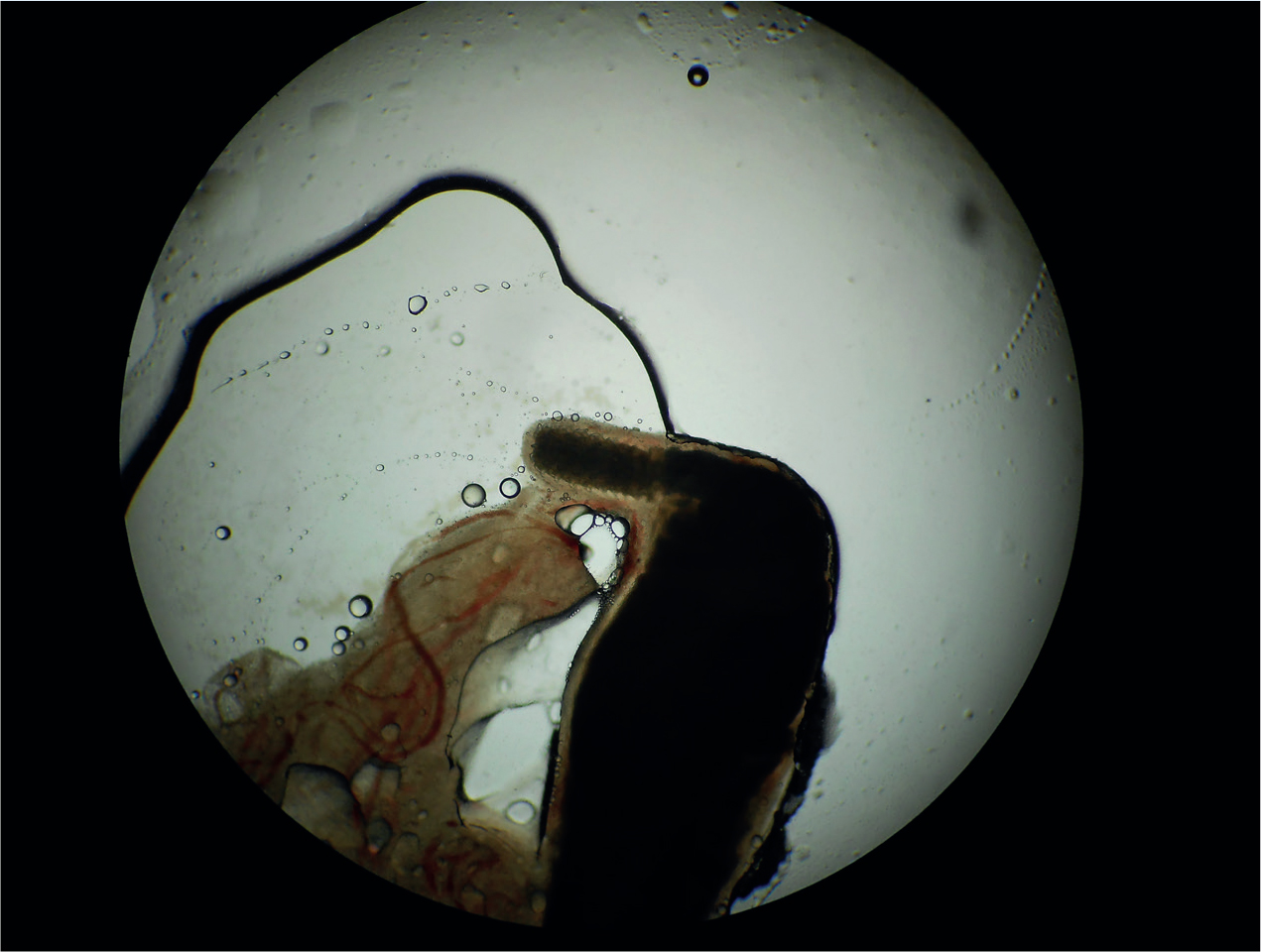

Thorny-headed worms may inhabit the intestines of hedge-hogs. Infections are often subclinical in adults but focal outbreaks of clinical infection in juveniles can occur with high levels of mortality. Adult worms may be passed in the faeces or found at post-mortem examination. They are 2–6 mm long with barbed heads (Figure 5) and the anchoring of these barbs in the intestinal wall can lead to ulceration of the mucosa, secondary bacterial infection, diarrhoea, emaciation and death. Infection may be diagnosed by the detection of larvated eggs in the faeces. The eggs are easily identified as the larvae already possess barbed heads, but the weight of the eggs requires sedimentation rather than flotation techniques for detection. The parasite can be eliminated with praziquantel as for fluke or with levamisole injections as for Crenesoma spp. lungworm, but supportive treatment is also required for the diarrhoea, antibiotics for secondary infection and anti spasmodics may also be required. The prognosis in clinically affected individuals is very guarded. The need for an intermediate host means there is no risk of transmission in the practice setting.

Conclusions

Veterinary nurses play a vital role in the rehabilitation and medical care of sick and injured hedgehogs. While parasites are often well tolerated by their hedgehog hosts, their potential to be transmitted between hedge-hogs, pets and people means that hygiene and accurate parasite diagnosis is important in keeping infections under control. When treating hedgehogs, accurate recording of weight for both drug dosages and to monitor response to treatment is essential.

KEY POINTS

- Veterinary nurses play a vital role in the rehabilitation and medical care of sick and injured hedgehogs.

- Parasitic infections in hedgehogs are common and often well tolerated.

- Most hedgehog parasites are not zoonotic but may be transmitted between hedgehogs or lead to infestations in practice.

- Good barrier hygiene and disinfection forms an important part of limiting transmission of parasitic infection.

- Regular recording of hedgehog weight is important both for drug dosing and to monitor response to treatment.