Ophthalmic disease is common in the veterinary patient population. Early identification can prevent life-threatening, vision-threatening and globe-threatening disease and nurses are well placed to both monitor and identify eye disease. This workshop discussed four essential clinical skills to aid in the early identification and prevention of disease:

- Assessing ophthalmic pain

- Measuring intraocular pressure

- Measuring tear production

- Using your phone as a clinical tool in eye disease.

The author is always happy to answer queries or offer advice by WhatsApp or phone (07782219868).

Assessing ophthalmic pain

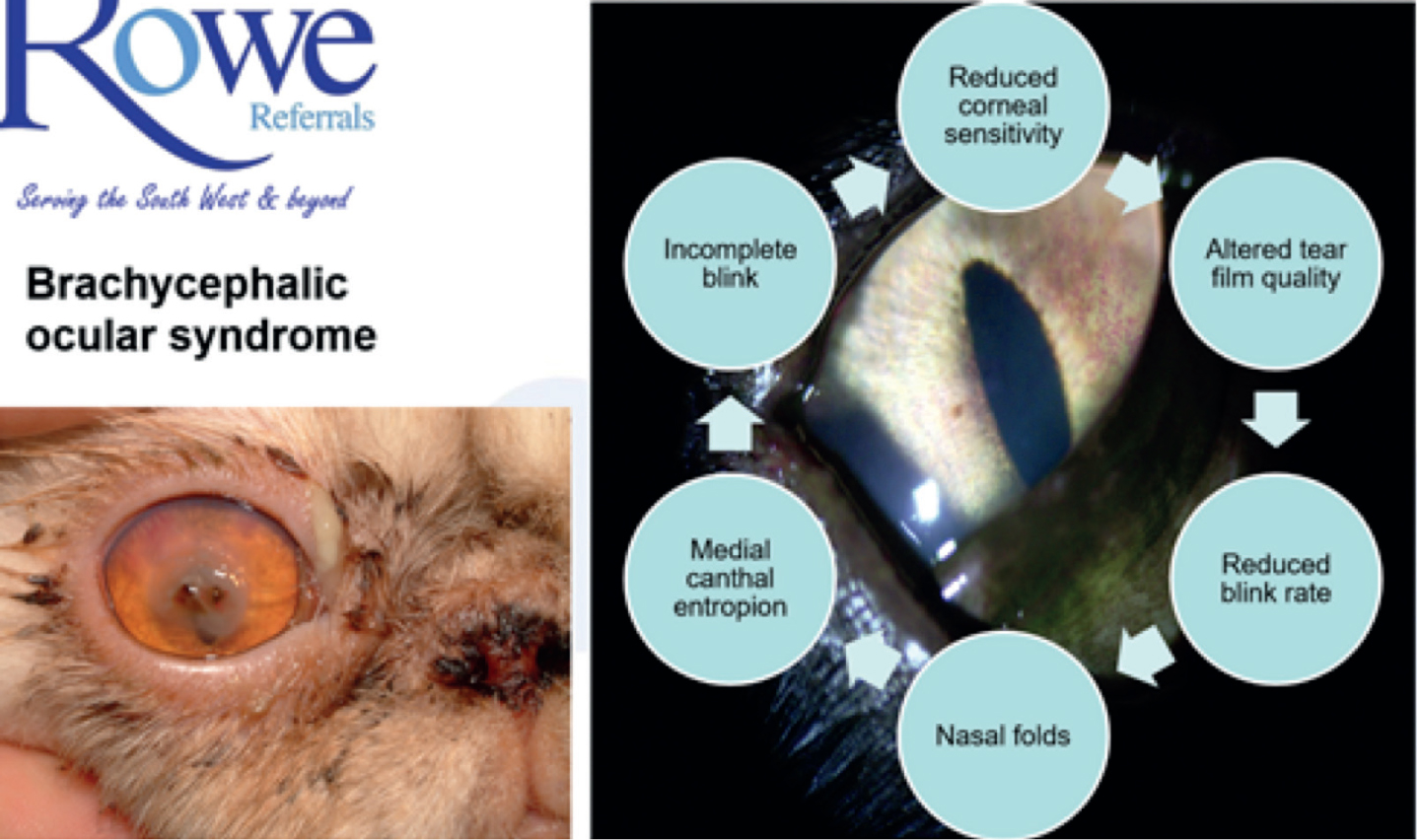

Demonstration of ocular pain is species and patient specific. Prey species tend to hide ophthalmic pain well as do certain dog breeds, notably many of the terriers. Of increasing importance is the reduction in corneal sensation we see associated with brachycephalic ocular syndrome (BOS). BOS affects small breed brachycephalic dogs and cats (Persians and to a lesser extent Burmese). Increased corneal exposure, poor blinking and chronic entropion leads to reduced corneal sensation which means that serious ocular surface disease (entropion, corneal ulceration and corneal sequestrum formation) may go unnoticed by owner and clinician alike. For this reason all small brachycephalic patients require good client education, life-long tear film supplementation and intensive corneal support during surgical interventions (e.g. neutering, dentistry).

The concept of the ‘triad of ocular pain’ helps us to pick up subtle signs of ophthalmic pain and also allows us to differentiate pain from conditions which while looking painful are not. This triplet of clinical signs is associated with ophthalmic pain and/or discomfort and applies to all species. Note that not all patients show all signs, and different sorts of ophthalmic pain will affect the outward signs shown. The signs are as follows:

- Blepharospasm (which includes increased blink rate)

- It is normal for both eyelids to blink at the same time (conjugate blinking) — unilateral blinking (winking) may be a sign of ophthalmic pain

- Note that this can be subtle and, if the patient is aware they are observed, hidden

- Note that reduced blinking due to nerve damage (facial paralysis) will give the appearance of increased blink rate in the normal eye

- Severe ophthalmic pain will lead to a closed eyelid and the increased facial muscle tone ‘the pain face’

- Lacrimation (increased tear production)

- Ocular surface pain, such as that caused by entropion or superficial corneal ulceration, tends to cause more lacrimation than intraocular pain

- Note that poor tear drainage can lead to tear overflow (or ‘epiphora’) which can mimic lacrimation

- Tear production can be quantified using the Schirmer tear test. Elevated tear production should always be assumed to be due to ocular pain

- Note that keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS) and BOS reduce the ability to increase tear production in response to pain — beware the normal tear production in the apparently painful eye

- Photophobia (aversion to light)

- Intraocular pain, such as uveitis and glaucoma, tends to cause more photophobia than ocular surface pain

- Note that mydriasis (pupil dilation) can also cause photophobia.

Chronic ocular pain shows many of the signs we associate with chronic pain caused by arthritis or dental disease notably:

- Temperament changes

- Altered sleep patterns

- Reduced appetite

And where vision is also affected:

- Disorientation

- Loss of house training.

Note however that, in general, all of the companion animals we deal with cope remarkably well with blindness (Figure 1), whereas the blind painful patient will often cope very poorly.

We use a modified pain scoring system for our patients which can be downloaded at www.theeyephone.co.uk (see also for more tips).

Measuring intraocular pressure

Disease affecting the intraocular structures are often vision threatening and in some cases life threatening. Intraocular disease often leads to changes in intraocular pressure (IOP) making the ability to measure IOP accurately a very important clinical skill.

Three commonly available techniques are applicable to veterinary patients:

- Rebound tonometry (The Tonovet, Icare®)

- Single use probes are bounced off of the cornea. The probe bounces quickly off a hard eye and more slowly off a soft eye

- No local anaesthetic required

- Must be used horizontally

- Affected by corneal pathology

- Our instrument of choice (Figure 2a)

- Applanation tonometry (Tonopen, Reichart)

- The tip of the instrument contains a small raised button which is pushed back into the tip when pressed against the cornea as the cornea is flattened (or ‘applenated’).

- Probe tip must be precisely applied at 90 degrees to the cornea

- SIngle use protective covers are essential

- Local anaesthetic required

- Corneal ulceration is more likely with repeated or inexpert use

- Despite being the gold standard for accuracy the risk of ulceration with repeated use means that we no longer routinely use this instrument in our clinic (Figure 2b)

- Indentation tonometry (The schiötz tonometer, Riester)

- A metal rod rests on the cornea through a hole in a corneal foot plate. The rod is allowed to indent the cornea and its movement measured, a soft cornea is indented more than a hard cornea

- Must be used vertically and with local anaesthetic

- Accurate and inexpensive (<£100) however requires a sedated or biddable patient and practice to use safely and accurately

- I always have one of these instruments to hand as a backup as it requires no batteries and is robust and, with practice, can give accurate results (Figure 2c).

Measuring tear production

Measuring tear production is an essential clinical skill which allows early identification of many ocular surface disease:

Decreased tear production can be due to:

- Keratoconjunctivitis sicca

- Decreased corneal sensation — most commonly seen in brachycephalic ocular syndrome and diabetic patients (Figure 3).

Note that increased tear production is always due to ocular pain or discomfort.

Tear production should always be measured from the same location (the lower lateral eyelid) and the time of day noted to allow both the diurnal variation in tear production to be accounted for, and the lacrimal stimulatory effects of cyclosporine and tacrolimus to be accounted for.

Gentle eversion of the lower lateral eyelid allows the bent end of the tear strip to be placed in contact with the relatively insensitive eyelid conjunctiva prior to allowing the lid to be gently re positioned against the cornea. This reduces reflex tear production from inadvertent corneal touch as well as making the test better tolerated. The diffusion of tears along the test strip is measured in mm at 60 seconds after application. Eversion of the lower lateral lid prior to removal reduces the risk of the tip tearing off and being left in the eye.

Note:

- Eyelid anatomy will reduce readings where the eyelids are not in their normal close corneal contact, e.g. giant breed dogs

- Tear production should be symmetrical in the normal patient and ocular pain expected to increase it markedly

- Cats have an unusually stable tear film and it can thus be normal to have a tear reading of 0 mm/min in some patients.

Photographing the eye — using your phone to save patients lives. ‘The 21st century pen torch’

Ophthalmic photography should be considered an essential clinical skill. It allows both identification and monitoring of a number of important ocular diseases and is a useful screening tool for many others.

Assessing the reflection from the back of the eye (the ‘tapetal’ or more accurately ‘fundic’ reflection) allows rapid recordable assessment of:

- Pupil size, shape and responsiveness

- Anisocoria — asymmetric pupil size, is not normal and may be caused by serious intraocular and potentially life threatening systemic disease, e.g. uveitis (inflammation inside the eye) or retinal detachment due to hypertension

- Dyscoria — abnormal pupil shape, is not normal and may also be caused by serious intraocular and potentially life threatening systemic disease, e.g. uveitis and feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV)

- Mydriasis — dilated pupil/s, may be caused by stress, excitement or benign ageing changes but may also be the first sign of serious disease such as retinal detachment

- Miosis — constricted pupil/s, is one of the primary signs of uveitis. There are no good causes of uveitis with life threatening systemic disease not uncommonly causing uveitis

- Visual axis clarity

- The visual axis is the transparent corridor light travels from the front of the eye to the back, it should be expected to be symmetrical, any asymmetry may be clinically important

- Corneal disease such as KCS and corneal ulceration will block the fundic reflection and is often readily visible

- Aqueous humour changes, bleeding (hyphema), pus (hypopyon), fibrin (seen in uveitis as strands of greyish tissue), aqueous flare (seen in uveitis) and lipid aqueous (seen in diabetes and pancreatitis) will readily dull or in some cases obscure the fundic reflection

- Lens opacities will dull, obscure or obliterate the fundic reflection. This is in contrast to nuclear sclerosis, a normal aging change which gives the appearance of blue/grey pupil but will not dull the tapetal reflection. All diabetic patients should be expected to develop cataracts and to do so suddenly. This often requires emergency surgical treatment so client education is essential.

Technique

The easiest technique is to use the video mode on your phone selecting the light to be on while recording. Practice getting as close as you can to the patient's eye while remaining in focus (Figure 5). Aim to record:

- Both pupils at the same time. Swing the camera away from the eye and towards it looking to see a direct pupillary light response (the pupil contracting) and then between the two eyes (the swinging flashlight test)

- Each pupil on its own, zoom in to get the eye to fill the screen while still seeing the fundic reflection but remember not to get so close you can't focus.

Conclusion

Ophthalmic disease is second only to dental disease in prevalence in clinics and the veterinary nurse's role in early idenitification and prevention is key. It is hoped that these four key skills equip the nurse clinician to do this more effectively.

KEY POINTS

- Ocular pain is expressed variably by species and condition, using the concept of the triad of ocular pain (lacrimation, photophobia and blepharospasm) helps us to identify pain.

- Assessing the tear film should be multimodal and include assessment of corneal reflectivity, the presence of mucoid discharge, blink rate as well as the Schirmer tear test.

- Intraocular pressure measurement is essential for the identification and management of intraocular disease.

- Assessing the reflections from the back of your patients’ eyes (the ‘fundic reflection’) should be an essential part of the clinical examination rapidly identifying serious ocular disease.