We have all been there — on day 1 after qualification, everything has changed. Suddenly you have gone from student to a fully qualified veterinary nursing professional. This is what you have been waiting for — the chance to work with animals, owners and colleagues as a fully formed member of the team — no longer having to wait for approval you are now able to make your own decisions. Why is it then that so many veterinary nurses and veterinary surgeons go on to find stress, upset and disillusionment within the profession? What is it that changes once people are qualified? Does anything change? Or it is more likely that people believe once qualified the questions and uncertainty felt as a student will somehow disappear, but reality is that doubts and questions can remain and even increase after qualification. All veterinary staff know that working with sick animals will be emotionally draining; do they think that they can cope with it and then find a few years later that, like a continuous trickle of water, it can wear down even the toughest of individuals?

Williams and Robinson reported in 2014 that most veterinary nurses thought their job was stressful. Owners may find themselves in an upsetting situation where a loved pet is ill or injured, often suddenly, and veterinary nurses are central to the care given to both the owner and animal. Veterinary nurses need to be able to combine the knowledge and practical skills of nursing, alongside good people skills in communicating effectively with owners and colleagues. Ridge (2016) reported that many recently graduated veterinary surgeons were disillusioned with the profession. Clark et al (2016) stated that the current training of veterinary students in the UK limits their abilities to manage uncertainty, unpredictability and undecidability and that problems arise when veterinary surgeons are ‘confronted by the precariousness of everyday practice’ (Clarke et al, 2016:603).

Human medicine is no different to the veterinary profession. A report from the General Medical Council (Monrouxe et al, 2014) stated that doctors found the transition from medical school to intern stressful. They felt unprepared for the change in responsibility, having to multitask, not knowing where to ask for help, and possibly having to work in or with an unfamiliar environment or facilities.

But what is meant by being prepared for practice? Working in veterinary practice encompasses so many different facets — knowledge of animals, anatomy and physiology, animal husbandry, nutrition, behaviour, medical and surgical nursing, anaesthesia, communication skills — the list goes on and on. Where does the reality of practice fit into this? Monrouxe et al (2014, 2017) defined being prepared for work as a doctor as personal readiness, knowledge, skills and attitudes including psychological and emotional aspects and professionalism. However, they developed this further to include lifelong learning, development and adaptation — enabling students to work with the challenges of a career. So, knowledge of the subject was part of this training need, but not all. Being prepared personally means knowing the subject matter and how to care for an animal and owner, but also how to care for yourself and recognise the emotional and psychological effects that the work and people bring.

Historically veterinary nursing training has focused on the animal and the owner and less so on the nurse. Knowledge of diseases and nursing care is all about what the nurse will do for the patient. Training in communication focuses on working with the owner and understanding the owner's needs. Very little training focuses on the needs of the nurse — what their own individual personality is; how they will deal with different situations; and the effect that some of the more stressful cases will have on them personally.

So, the question must be asked — how can you prepare students for the day to day challenges of working in practice, allowing them to care for the patients, develop their nursing skills but also develop their own confidence in working with animals, owners and colleagues? Moving from the familiarity of a practice where people have worked as a student, to a new job which could also be away from family and friends is stressful. Students need to be ready for these challenges and know that they are not alone.

A study carried out by this author (Fraser, 2015, 2016) found that the type of problems faced by veterinary nurses in practice included time management, dealing with complaints, emotional or moral difficulties, and work–life balance (See Table 1). This questionnaire based study asked qualified veterinary nurses about their own experiences of practice and education. Looking specifically at how the reality of practice should be taught to students, respondents did believe that this subject matter could be taught both as a subject in its own right, or integrated within other subjects such as ethics. Deeper analysis of these results identified that respondents believed that students needed to understand the requirements of practice, be able to cope with physical, technical and emotional aspects of practice, be aware of support that is available to them and have realistic expectations of life in practice. An interesting point was that many respondents felt that as a student they had been cushioned from the reality of practice.

| There are a variety of different challenges/stressors in veterinary practice |

|---|

| The need to be engaging and responsive to clients |

| Care about our patients |

| Good communication |

| Long hours/social isolation |

| Unexpected clinical outcomes/lack of control of these cases |

| Unrealistic expectations of clients |

| Litigation/RCVS |

| Personality/personal morals/moral stress |

| Expected to cope? |

So how do you prepare students for practice and ensure that they have realistic expectations but keep their enthusiasm for the profession? How can students feel empowered and ready to work in practice, able to cope with whatever happens?

This question was discussed at the 2017 VetEd conference, where many lecturers and veterinary educational professionals from UK, Ireland, other countries in Europe, USA and Canada came together to examine the different methods currently implemented to prepare both veterinary and veterinary nursing students for the reality of practice. VetEd is a national/international conference originally set up by the UK Veterinary Schools Council (VSC) to bring together educators from UK veterinary schools, but in recent years this has expanded to include both European Vet Schools (Utrecht and Dublin) and veterinary nursing educators.

Delegates attending the VetEd conference in 2017 identified various initiatives from their own teaching (Table 2) including making alterations to the admissions process, spending time and/or modules on wellbeing/resilience, peer mentoring programmes and reflection.

| Initiatives/teaching methods identified at VetEd workshop (2017) |

|---|

| Mindfulness |

| Reflection |

| Resilience |

| Use of role play |

| Mentoring programme |

| Specific module on workplace demands for veterinary professionals |

| Specific week devoted to mental health, wellbeing and coping strategies |

| Communication courses |

| Ethics and regulation gradually incorporated into course material |

| Closed door sessions where students can talk about practice in confidence |

| Admission process |

Wellbeing and resilience have both been highlighted in the veterinary profession by the Mind Matters initiative, British Veterinary Nursing Association and Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons and are now included in many veterinary training programmes (Mind Matters, 2017). However, there is still some resistance to this from students who may not fully understand the importance of such classes. Incorporating wellbeing and mental health topics into other subjects may be needed to engage students with the subject matter (VetEd, 2017).

Whitcomb (2014) describes the concept of the formal curriculum (what training is planned), the informal curriculum (what is being taught) and the hidden curriculum where students learn about professionalism and values through their experience of education. It is therefore suggested that the hidden curriculum plays a central role to the training of students about the reality of practice. Respondents to the study by Fraser (2016) clarified that while they agreed the reality of practice could be taught, it would only be successful if lecturers had experience of practice and were honest about their own experiences of practice. However, the hidden curriculum can also be found to deliver negative aspects of training. Opinions and bias can be transferred to students, and care needs to be taken to maintain an independent position, informing students to then allow them to make their own decisions about their career.

Ridge (2016) reported that mentoring from peers and colleagues in practice was a useful support mechanism. Peer support was also implemented by some of the organisations attending the VetEd conference. This is a useful mechanism for students as it gives them the chance to learn from others who will have gone through the same experiences and are not seen to be judgemental. Spielman et al (2015) examined a peer support programme within a veterinary school that focused on pastoral care rather than academic matters. Students were generally positive about the programme but felt that confidentiality was a possible problem due to the small numbers of people involved. The same problems could be found with veterinary nursing programmes that may have even smaller cohorts than veterinary programmes.

Students need to be aware of the challenges that are faced in everyday practice: to understand that it is normal to find some cases difficult, or emotionally draining; to know that there will be cases where they may not agree with the course of action taken by a colleague or an owner; to know that complaints will be made about them and to know that mistakes will happen no matter how good a veterinary nurse they are and to know that this happens to everyone at some point in their career.

Catherine Oxtoby of Veterinary Defence Society (VDS) has highlighted the second victim syndrome where the nurse or clinician caring for a patient when something goes wrong, can go through a process of self-trauma as they reflect on what happened (Clark, 2017). While training cannot change the unpredictable nature of working with animals and the fact that things will go wrong, it could give nurses the skills needed to deal with problems when or if this happens.

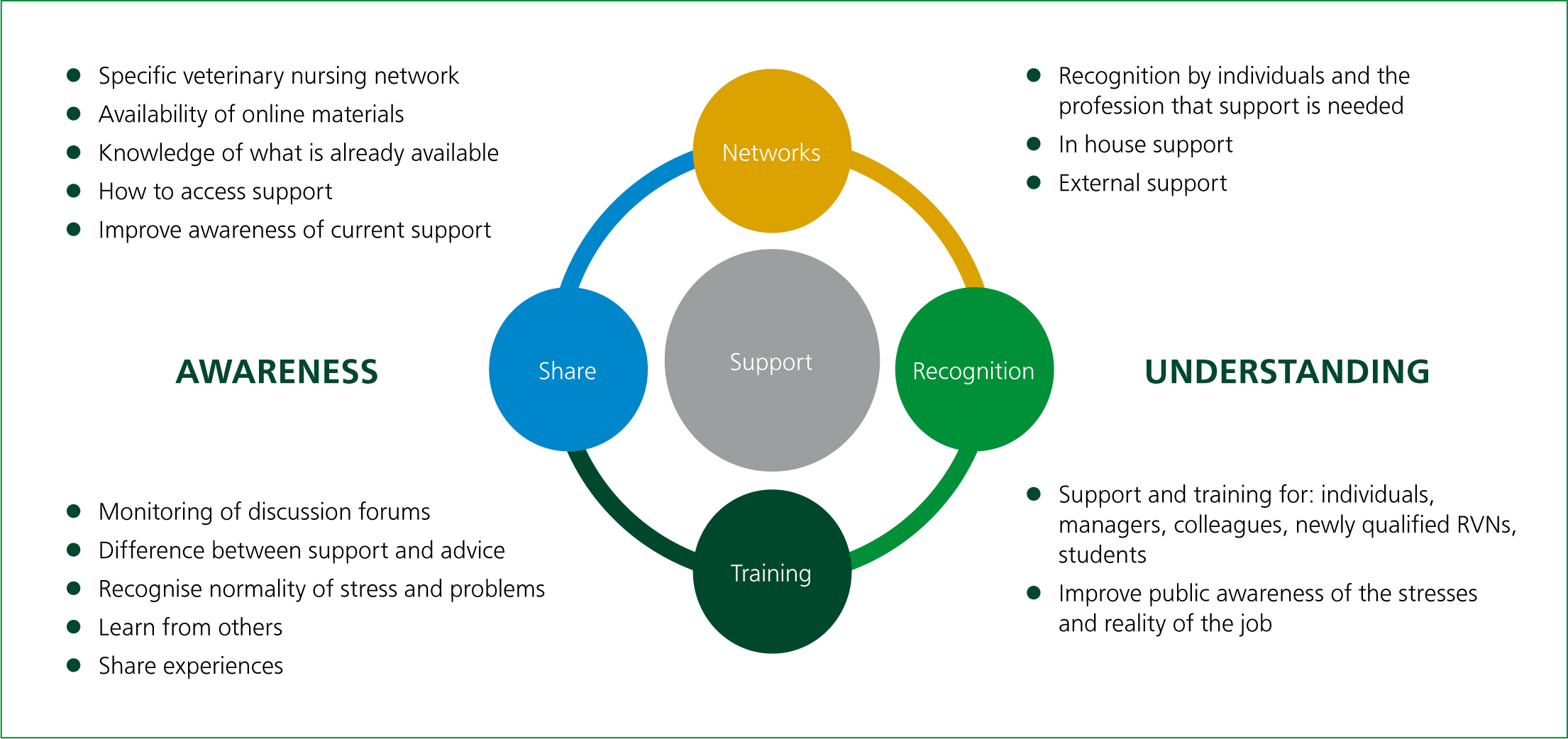

Looking forward, to support in practice, work by the author identified a number of different factors that veterinary nurses would like to see to put into place to help them in general practice (Figure 1).

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is clear that much is already in place to support veterinary nurses through training to prepare them for the transition to working in practice. The high profile of this subject, will hopefully lead to a greater understanding of the challenges that are faced in everyday practice and a greater willingness for all members of the practice team to be honest about their own experiences.

However, none of this work changes the underlying factors that make veterinary nursing stressful and challenging. Initiatives such as VN Futures are required to challenge the current environment in which veterinary nurses care for patients.

It is hoped that this paper has presented an overview of the different educational tools and support that can be incorporated into veterinary nursing education to enable veterinary nurses of the future to meet the challenges of working within this profession.