Previous research relating to student veterinary nurse (SVN) support in practice has been published in the Journal of Veterinary Medical Education (Holt et al, 2021, 2022). The aim of this twopart article is to disseminate the key information from this previously published work and draw on the combined experience of the current authors relating to the role of the clinical supervisor and the training practice team within the clinical learning environment (CLE).

Student experience

The experiences a student has in the CLE are critical in preparing student human nurses (SHNs) for their career, allowing opportunities to put theory into practice, develop clinical skills, and build professional identity and confidence (O'Mara et al, 2014; Arkan et al, 2018; Parvan et al, 2018; Ramsbotham et al, 2019). While no such research for SVNs could be identified by the authors, the two professions' practical training can be considered comparable. This is evidenced by the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (RCVS) Standards Framework for Veterinary Nurse Education and Training, which adopted the structure and format of the Nursing and Midwifery Council Standards of Proficiency for Registered Nurses (RCVS, 2021). Therefore, the veterinary nursing profession can currently look to the literature available in SHN experiences of the CLE to help signpost key advice for clinical supervisors.

The supervisory relationship that SHNs have in the CLE has been cited as the most influential factor in determining student satisfaction levels (O'Mara et al, 2014; Papastavrou et al, 2016; Parvan et al, 2018). There is evidence in SHN research which demonstrates that there can be poor supervisor practice, including a lack of feedback and appropriate communication, as well as poor teaching skills with no structure, leading to either reduced learning opportunities, or ‘throwing students in the deep end’ (Gray and Smith, 2000; Arkan et al, 2018; Kalyani et al, 2019). Poor clinical supervisor practice can cause confusion in student expectations and professional identity, especially when the clinical supervisor is an inappropriate role model and expresses negative attitudes towards their own career (Kalyani et al, 2019).

Clinical supervisor role and attributes

Research available in other comparable professions and countries has examined the ideal qualities for a clinical supervisor to demonstrate, based on clinical supervisor and student opinions. Within this research, there was strong agreement identifying clinical competence and reasoning, enthusiasm, positive interpersonal skills and support of the learning environment as key skills and attributes which are vital to the clinical supervisor role (Figure 1) (Chitsabesan et al, 2006; Sutkin et al, 2008; Fluit et al, 2010; Foster et al, 2015; Francis et al, 2016; Perram et al, 2016; Faithfull-Byrne et al, 2017). It is evident that some of the skills and attributes identified as desirable go beyond the clinical competencies expected of qualified veterinary professionals.

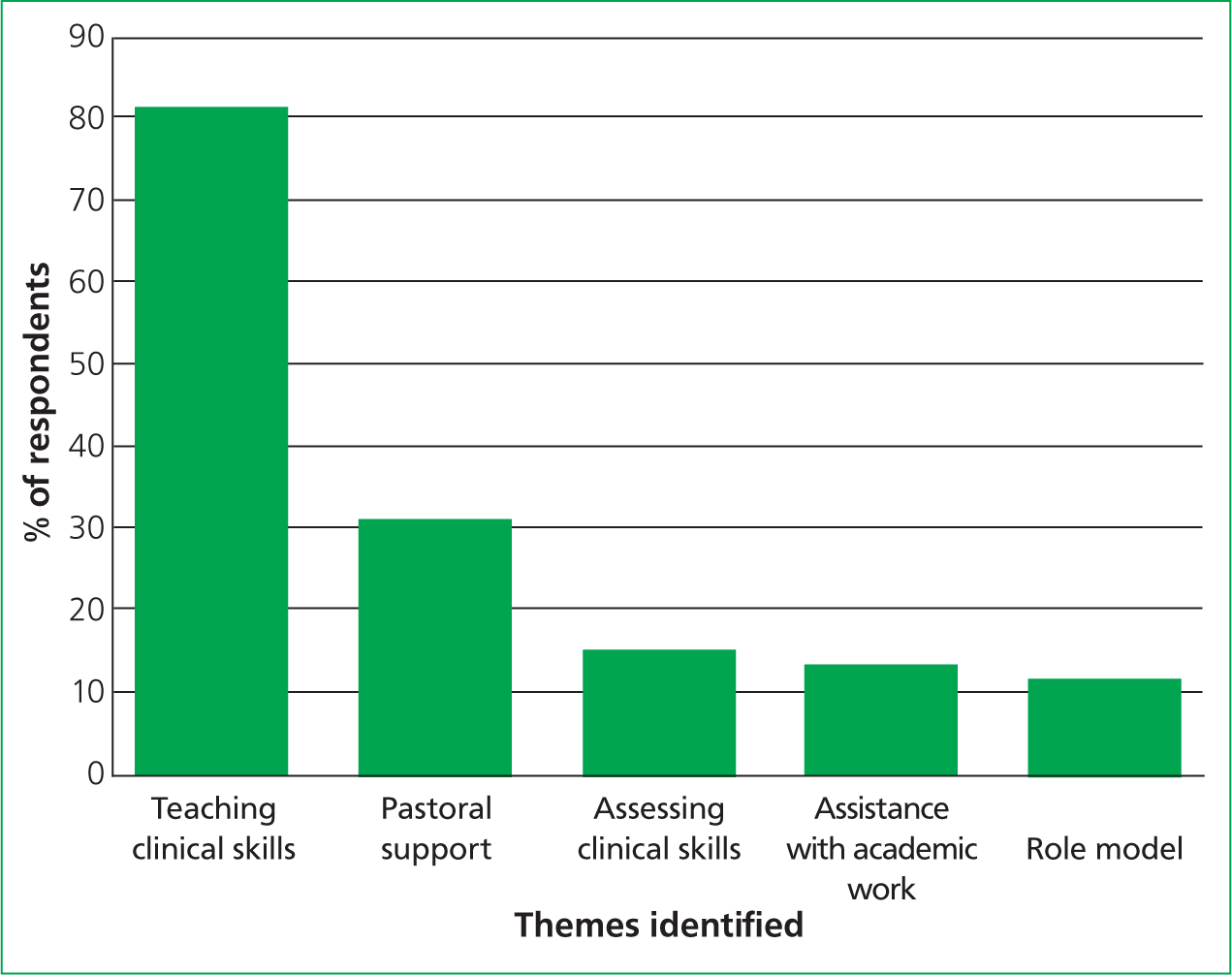

Clinical supervisors in UK veterinary practices were asked to describe associated role responsibilities in their own words. The themes identified are detailed in Figure 2. These findings are positive, in that most of the SVN clinical supervisors have identified teaching clinical skills as an important aspect of the role. However, appropriate interpersonal skills, enthusiasm and adequate training for the role are also important to achieve the desired practice for student support (Chitsabesan et al, 2006; Sutkin et al, 2008; Fluit et al, 2010; Foster et al, 2015; Francis et al, 2016; Perram et al, 2016; Faithfull-Byrne et al, 2017).

Clinical supervisor training

When reviewing the opinions of clinical supervisors in human nursing, a high level of importance was consistently placed on the need for education and the further development required for an individual to be successful in the role. (Maxwell et al, 2015; Nyoni and Barnard, 2016; Oprescu et al, 2017; Ryan and McAllister, 2017; 2019). This is echoed in the opinions of veterinary nursing clinical supervisors, with 47.5% of those surveyed stating that they did not feel well prepared for the role after training (Holt et al, 2021). In addition, three themes were identified by an open question asking for recommendations for future training as detailed below (Holt et al, 2021).

Theme 1: Clinical Supervisor Course Content was identified by 55% (n=44). There was a large call for more content on supporting students' learning and how to encourage struggling students.

‘Personal support for the students as some need encouragement at different times, I don't feel this is prepared for in training…’

(Respondent 29)

There was also a call for more training and information about use of the online logs for recording clinical skill achievements. More guidance on what cases can be used for specific skills was also called for.

Theme 2: Clinical Supervisor Course and continuing professional development (CPD) Design was identified by 23.7% (n=19). Generally, there was a call for longer initial training with support from experienced clinical supervisors. Some suggested that the training should lead to a formal qualification. Targeted CPD with support and discussions with other clinical supervisors was also deemed valuable.

‘I find sessions with other clinical coaches so important to speak to other CCs [clinical coaches] to whom you can pass on your experiences or gain ideas from…’

(Respondent 2).

‘I feel there should be a more detailed course to become a clinical coach. Perhaps even a certificate.’

(Respondent 33)

Theme 3: Institute Communication was identified by 13.7% (n=11). Some respondents called for more support from the institute the student was attending.

‘Better communication between clinical coach and training centre’

(Respondent 52)

‘Have more visible support for coaches especially to those who don't have internal support’

(Respondent 23).

There is currently no nationally standardised curriculum for clinical supervisor education and development in the veterinary nursing profession. It is up to the individual accredited education institutes (AEIs) to interpret the RCVS guidance on the requirements for an individual to become a clinical supervisor (RCVS, 2021). This includes the requirements that they:

‘receive relevant induction, ongoing support, education and training which includes training in equality and diversity’.

Plus the requirement that:

‘All clinical supervisors must complete clinical supervisor training and be issued with certificates of attendance. Subsequent clinical supervisor standardisation should be completed a minimum of every 12 months with further training and support for those identified as higher risk.’

It has been assumed that much of the teaching for SVNs in the CLE is performed by staff who have no formal training on the principles of education (Williams, 2016a). Veterinary nursing students are considered to present similar challenges as those discussed for students in other healthcare disciplines (Sibson, 2011a, 2011b; Cottrell, 2013). This will require the veterinary nursing clinical supervisor to demonstrate the non-clinical skills highlighted by other clinical professions such as excellent communication, enthusiasm, providing clear feedback and building rapport (Sibson, 2011a, 2011b; Williams, 2016a, 2016b).

Given the importance of the clinical supervisor role to the future of the profession, and to reducing student attrition rates, increasing student satisfaction and developing professional identity and confidence, careful consideration should be given when practices select individuals for this role. Those who feel pushed or less keen to undertake this role can have reduced self-reported confidence (Batt-Williams and Yon, 2022), which could have negative consequences for student training and professional development. In addition, AEIs should ensure clinical supervisor training, CPD and ongoing support is provided that comprehensively incorporates all the requirements and challenges of the role.

Guidance for clinical supervisors

Educational institution assessment of Day One Skills

Although Day One Skills (DOS) are defined by the regulatory body, the RCVS, the approach to tracking them is not standardised, with each AEI taking a different approach. The RCVS Nursing Progress Log tool is optional for AEIs to adopt (Guthrie, 2016) and there are other formats in use including the Clinical Skills Log. In the authors' experience, a clinical supervisor could be working with more than one AEI, depending on where students are attending, which can create challenges when interpreting guidance and advice.

Clear communication between the clinical supervisor and each student's AEI is essential. Familiarity with the online tool used to log practical competency of DOS (e.g. Nursing Progress Log or Clinical Skills Log), and an overview of each student's curriculum, is also important because AEIs will differ in their requirements.

AEIs have a significant role in providing clinical supervisors with support and setting targets, and the advice provided will differ between institutions; hence the AEI should be the first point of contact for clinical supervisors with course and support queries. All clinical supervisors are required to attend a standardisation event at least annually, as per the RCVS (2021) guidance. Standardisation events are provided by AEIs, with the expectation that training standards are maintained, and the latest guidance is being followed by all clinical supervisors and training practices.

Student induction and setting expectations

Clinical supervisors are an integral part of SVN training, mentoring them through their clinical skills and development of professional identity. They uniquely ensure the nascent veterinary nurse develops practical competency, in addition to supporting the application of their academic knowledge. First experiences within a CLE are likely to be a daunting prospect for most SVNs and have been reported to create anticipatory fear in student human nurses (Gray and Smith, 2000; Rajeswaran, 2016). The clinical supervisor can alleviate this fear by ensuring that the first few weeks are structured to include practice orientation, staff introductions, health and safety inductions and general practice protocols and routines. The clinical supervisor can advise the team when a new SVN is starting so they can be mindful and welcoming. Assigning a ‘buddy’ in this stage, a more experienced student or newly qualified registered veterinary nurse (RVN), for example, can support a sense of belonging. Remember responsibilities towards the SVN regarding equality, diversity and inclusivity and ensure tailored training to support each student's requirements.

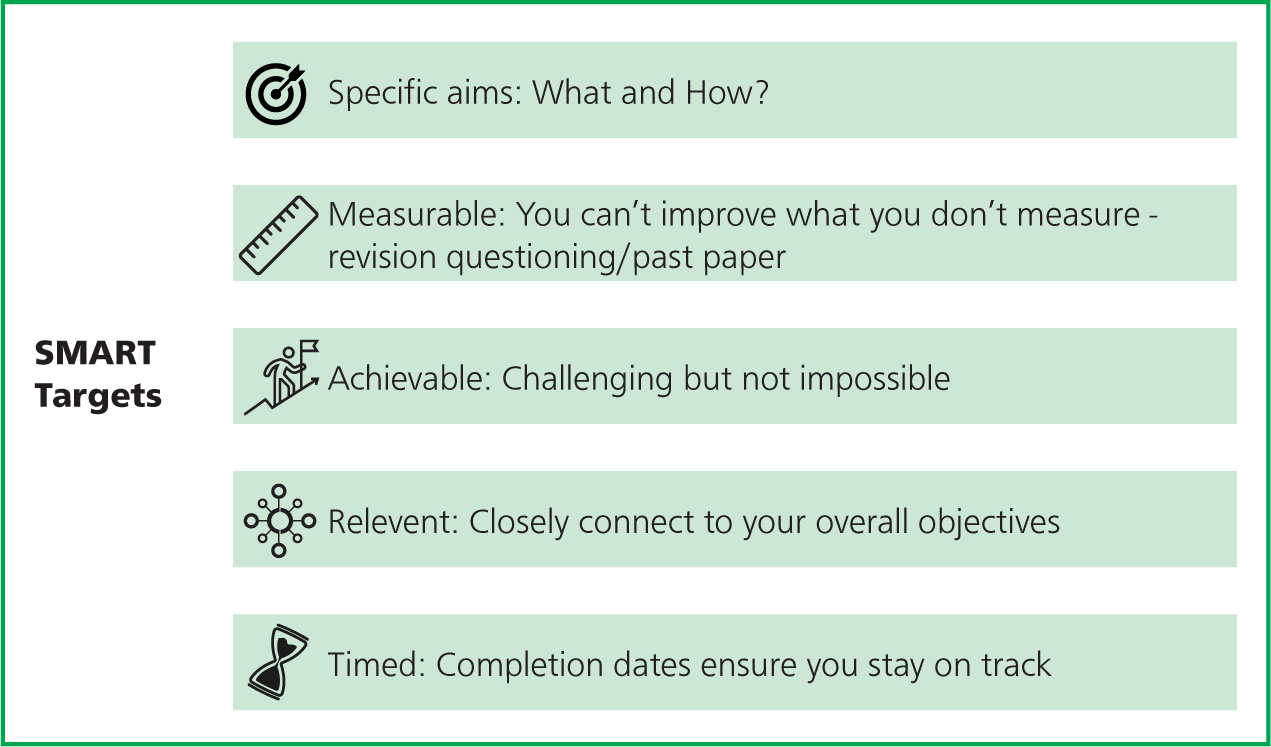

Once the student has begun training in earnest, it is important to gain an understanding of how they are settling in and performing. Gather feedback in this regard from the team and look to identify specific examples of where the student has performed well or where improvements can be made. These points can then be discussed and documented with the student. Set up regular meetings with the student and look to gain further support through signposting where necessary to the associated AEI. Structure goal-orientated discussions, where the SVN identifies what they would like to achieve, facilitated by the clinical supervisor. Use the GROW model for coaching as well as setting SMART targets that are easily achievable to start building motivation (Figure 3).

The GROW model allows a consistent, structured approach to plan each conversation in advance:

- Goals write them down and find out what the student wants from the session

- Reality encourage self-reflection, ask open questions, try not to give answers (What is happening? What effect does it have? What skills do you need to develop?)

- Options allow the student time to consider their preferred approach and plan

- Wrap up identify steps and objectives, write an action plan, i.e. a tutorial record.

A collaborative practice approach should also be taken to supporting students, with more experienced clinical supervisors mentoring newly trained clinical supervisors. The second article in this series will provide more detail on how the practice team can also be involved with student support.

Models of learning

There are several models that can be used to explain the stages in which students learn and develop new skills.

Decisions of competence are made by clinical supervisors relating to the practical skill performance of SVNs. Levels of competence in clinical skills can be defined using the concept that has been accredited to multiple authors and is known as the Conscious Competence Model (Keeley, 2021):

- Level 1 — Unconscious incompetence

- Student is unable to evaluate their own skill level (Caution required)

- Level 2 — Conscious incompetence

- Student is aware of their lack of ability in relation to the desired level

- Students can either become motivated to learn or stagnate here if not supported appropriately

- Level 3 — Conscious competence

- Student is ready to be confirmed competent in the skill, but it still requires concentration and attentiveness when they perform it

- Level 4 — Unconscious competence

- This would relate to an advanced qualified professional post registration

- Skills become innate or second nature.

Clinical supervisors need to assess fairly the acquisition of skills, within the CLE. Online tools, such as the Nursing Progress Log (NPL) have been created to document the journey to becoming competent at the DOS required. The AEI is responsible for standardising this process and ensuring consistency between the individual training practices.

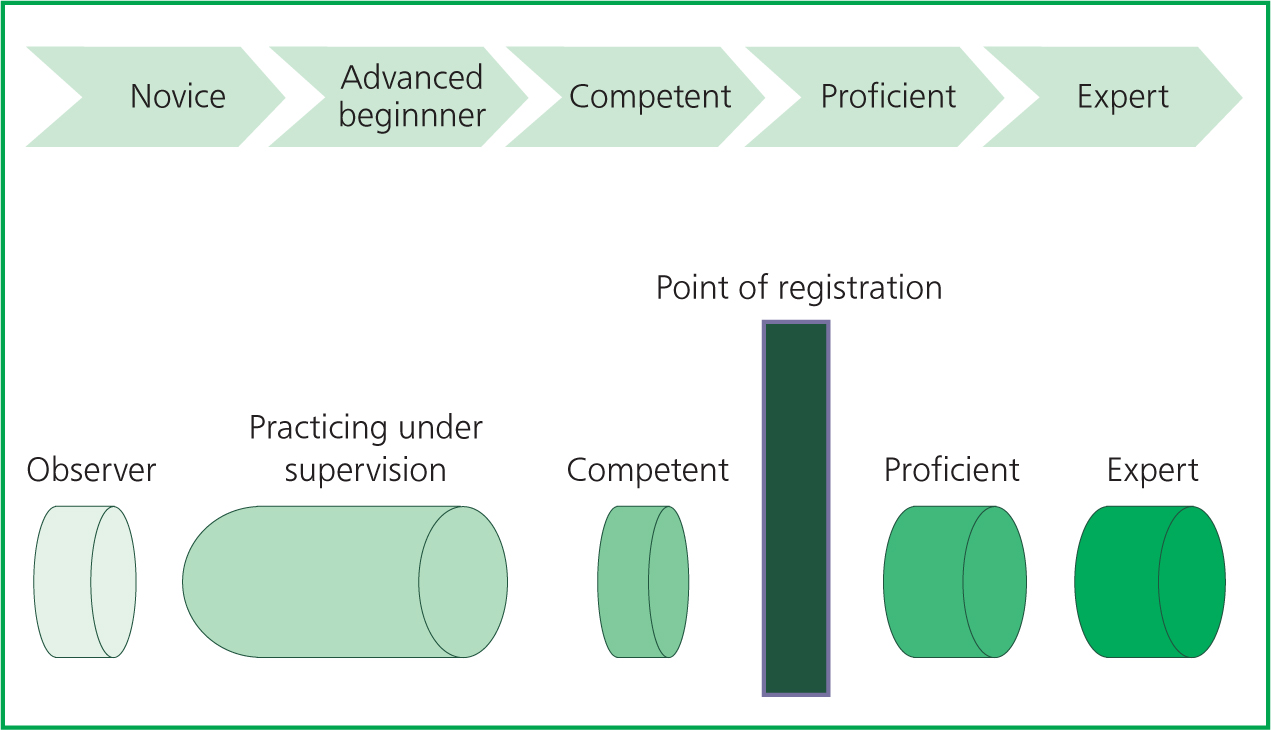

The Dreyfus Model of skill acquisition has been applied to nursing theory and documents a progressive transition in skill based on experience (Figure 4) (Benner, 2004; Dreyfus, 2004). The novice or nascent student starts with little or no experience and can only observe or follow instructions given. Competence develops after having considerable experience during the ‘advanced beginner’ stage of the Dreyfus model, which is documented as experiential learning on the SVN online log. Post qualification, the newly registered veterinary nurse will progress to proficient, with the final stage being to become expert in the field.

However, it should be recognised that a ‘day one competent’ person is the standard set by the RCVS as the minimum for a newly qualified nurse to practice a skill safely and autonomously under the direction of a veterinary surgeon (Figure 5). Newly qualified nurses will not be as proficient or expert as an experienced professional.

Previous research in human nursing has identified a ‘failing to fail’ phenomenon (Hughes et al, 2016; Davenport et al, 2018). This relates to the supervisor giving the student the ‘benefit of the doubt’ when conducting assessments and can be related to personal or professional reasons (Docherty and Dieckmann, 2015). However, it has been recognised that the issues appear generic and, therefore, equally applicable to veterinary nursing students (Sibson, 2011a). Clinical supervisors should have the confidence to demonstrate skills, appropriately assess them, declining competency or referring SVNs back to the AEI, as required, as an essential safety net for the profession (Batt-Williams and Yon, 2022).

Supporting the struggling student

Regular documented meetings will identify the individual level of support required and will help the clinical supervisor and student develop an appropriate relationship. This is particularly important as it will help identify any pastoral needs alongside progress and performance concerns. A student who is experiencing poor mental health and wellbeing will find it more difficult to learn at the appropriate pace, so identifying factors affecting their progress early on is vital (Davenport et al, 2018). While clinical supervisors are not required to be counsellors, there is a responsibility to prioritise the wellbeing of students within the RCVS Framework Standard 1.2 (RCVS, 2021). Veterinary nurses may also refer to their practice human resource policies and protocols and or the AEI, if appropriate to the student's employee status.

Ascertain gaps in clinical competency rather than clinical knowledge. Consult with the AEI, as they can provide support to clinical supervisors in establishing a plan for appropriate teaching strategies that will nurture self-confidence. Clinical simulations, for example, allow students to apply learning in a controlled clinical environment, facilitating immediate feedback, peer modelling and opportunities to practice skills. Ensure all feedback is documented and signed by both parties to enable tracking of progress and performance, and provide evidence of support and guidance. This can be used to refer back to with the student to reflect on progress, or repeated concerns. It is also highly advisable to upload these documents to online learning logs to facilitate access by the AEI.

Clinical reflective journalling by the student can be an effective way to facilitate learning for nursing students (Hwang et al, 2018). This can help students to cope with stressful clinical cases and can facilitate coping strategies (Nelms Edwards et al, 2019). Reflective models such as Gibbs can be used to guide and improve students' critical reflective thinking when considering their case involvement (Ardian et al, 2019).

Benefits of becoming a clinical supervisor

Understanding the benefits of undertaking a job role can help contribute to the levels of empowerment and job satisfaction experienced by an employee by increasing engagement with that role (Kanter, 2008). Kanter's 1977 empowerment structures of an organisation are still relevant today and can be linked to an individual's need for opportunity and power to succeed, opportunity for development and power to access the tools to achieve this in an effective manner (Spence Laschinger et al, 2010). Currently, the role of clinical supervisor can be carried out by either RVNs or veterinary surgeons and with many RVNs stating that they do not feel fully utilised by management, delegating the role of clinical supervisor to RVNs could therefore help to create a more satisfactory working environment (Batt-Williams and Yon, 2022; Vivian et al, 2022). The RVN must be aware that the clinical supervisor has additional workload responsibilities, such as mentoring, teaching and coaching; however, research suggests that the role allows for the development of a nurturing, open and positive working environment for all those involved and therefore can be beneficial to the professional development of an individual (Morrison and Brennaman, 2016; Batt-Williams and Yon, 2022). At the same time, delegating this role to RVNs could relieve workload pressure from veterinary surgeons (Davidson, 2017).

RVN utilisation, whether it is for Schedule 3 delegation or role development, should be considered on an individual basis of competence, experience, and confidence (RCVS, 2022). Veterinary professionals, the clinical supervisor and management personnel must therefore always be mindful that it is carried out correctly and not just to fill a void of satisfaction (Vivian et al, 2022).

Considering current concerns around RVN retention in practice (Johnson, 2021; Vivian et al, 2022), it is important to maintain a sufficient number of experienced RVNs to ensure a bank of nurses who can pass on their knowledge and expertise to new generations (Coates, 2015; Imrie, 2021; Vivian et al, 2022). Undertaking the role of the clinical supervisor enables individuals to develop and promote professionalism through being an active role model in the practice (Morrison and Brennaman, 2016). As discussed, being on hand to demonstrate best practice of clinical skills and assisting with academic work are key functions of this role, which can help to increase perceptions of professional identity of the individuals involved (Page-Jones and Abbey, 2015). The paper by Page-Jones and Abbey (2015) seeks understanding about career identity and its impact on individuals and organisations in the light of industry consolidation. Findings suggest that career is central to identity for many veterinary professionals who tend to have a strong sense of self; this is particularly evident around self as learner, technically competent teacher and educator, ethical and moral, and dedicated and resilient. Consequently, mismatches between ‘who I am’ and ‘what I do’ tend not to lead to identity customisation (to fit self into role or organisation). Clinical supervisors can demonstrate professional communication between colleagues and with clients, provide pastoral support for students who are just beginning to learn their way around the practice and help alleviate concerns that may develop during the learning journey (Davies et al, 2011). Time since graduation should not be overlooked when selecting individuals to become a clinical supervisor. New graduates are often able to provide a more empathetic outlook which is linked to the recent achievement of the similar educational journey, while those with longer lengths of service are more likely to cope with problems that arise within the workplace (Sygit, 2009; Morrison and Brennaman, 2016). Overall, the enjoyment of teaching allows a clinical supervisor to learn from and build on a student's knowledge, develop critical reflection skills and create an atmosphere where all contributions are valued (Davies et al, 2011; Morrison and Brennaman, 2016).

The lead author approached two current clinical supervisors for their comments on the benefits of undertaking the role. Their responses, which can be seen below, demonstrate the positive benefits they have personally identified.

Georgina Haddrell (RVN) stated:

‘Empowers me as I am supporting and passing on my knowledge and skills as well as helping someone grow in their development and training. Professionally I think people respect you for helping and supporting others through training. I am also passionate about developing veterinary nurses' skills and helping keep them in the profession.’

Amy Homer (MScVAA, RVN, PGCertPain, GradDipVN, NCertACC, PGCAP) stated:

‘For me, I find the benefit of being a clinical supervisor is that I get to actually see nurses progress and that I can support them through not only the theoretical but also the practical elements. This is a part of my role that I gain a lot of professional and personal satisfaction from — I have always had the attitude that we all were training once, and that our students should have a friendly and non-judgemental environment to learn in, that allows mistakes (as they make us learn!) but in a supportive way.’

Conclusions

To develop the clinical skills and professional behaviours appropriate to the veterinary nursing profession, student veterinary nurses require appropriate support to navigate the complex clinical learning environment. The clinical supervisor plays a key role in providing this support alongside the practice team and accredited education institutes. A structured, measured and individualised approach should be devised for each student, in line with the requirements of their programme. It is important to consult with the associated AEI regularly to ensure appropriate goal-setting and flag any pastoral, progress or performance concerns early to facilitate timely support. While the clinical supervisor role can be challenging, there are rewards too, such as increased job satisfaction and a sense of professional identity.

KEY POINTS

- Supporting student veterinary nurses in the clinical environment can be challenging and must be managed carefully, considering the individual needs of the student.

- A supportive and professional clinical supervisor is vital for the professional development of student veterinary nurses.

- With careful planning and preparation, the clinical supervisor can support the learning environment to create a safe space for students to develop confidence and skill acquisition.

- The role of the clinical supervisor does pose challenges but can also be extremely rewarding both personally and professionally.