Cats are increasingly living much longer lives; it is now not uncommon for cats to live into their late teens. Consequently this means older cats are more frequently presented into veterinary practice for treatment and care. One of the more common conditions seen in older cats is chronic kidney disease (CKD) (International Cat Care, 2013).

Nursing care of patients with CKD is well established but it is the author's opinion that this is currently limited to the management and nursing care of the disease process. Patients with CKD are also likely to experience pain — both physically and emotionally. Pain is a complex process and as well as being in physical pain from the disease process, patients with CKD may also be experiencing emotional pain during periods of hospitalisation and during diagnostic tests. The emotional side of pain may be experienced as a consequence of physical pain but it could also be experienced independently (McMillan, 2003). This is referred to as emotional pain, in humans this type of pain can be caused by conditions such as anxiety and grief. While animals may not experience grief in the same way as humans they are likely to suffer from anxiety and a decreased level of mental wellbeing when suffering from chronic conditions such as CKD.

Pain monitoring and management have advanced during recent years but this has largely been limited to the monitoring of acute post-operative pain (Flecknell, 2008). Pain scoring charts have been developed for use in both cats and dogs however validation has only been achieved in dogs. Pain management in cats has also fallen behind that of dogs due to misconceptions in how to monitor pain and the side effects of analgesic drugs (Robertson and Taylor, 2004).

Hellyer et al (2007) believe however that pain management is fundamental in all patients regardless of the reason for presentation.

Pain

Pain is defined as a sensory and emotional experience caused by actual or potential damage to tissue (The International Association for the Study of Pain, 1994). The sensory aspect of pain can be caused by illness or injury and is usually referred to as physical pain. Physical pain can lead to a negative emotional experience (e.g. distress) and can affect a patient's behaviour and wellbeing. Physical pain can cause many negative side effects both physiologically and emotionally (Sparkes et al, 2010) as shown in Table 1.

| Physiological | Emotional |

|---|---|

| Increased cardiac output | Distress |

| Secretion of stress hormones | Depression |

| Anorexia | Anxiety |

| Impaired respiration | Fear |

| Raised blood pressure | Frustration |

Both the physiological and emotional side effects can result in the patient suffering. Suffering is often seen as the experience caused by physical pain (Reid et al, 2013). However suffering can also occur independently of physical pain and can be a result of emotional pain (McMillan, 2003).

In animals, this side of pain is often overlooked (Grant, 2006). McMillan (2003) agrees and suggests that the emotional side of pain is often neglected; veterinary professionals pay more attention to the physical causes of pain. Reid et al (2013) also suggest that veterinary scientists have been slow to recognise the importance of using tools to measure this side of pain in relation to a patient's quality of life.

Pain in CKD

The term CKD is used to describe the irreversible and progressive loss of kidney function (Alguire and Darling, 2012).

The main roles of the kidneys are to help maintain fluid balance and excrete waste products. In doing this the kidneys help maintain the body's natural homeostasis. Another important role is the regulation of circulation. Many of the clinical signs of CKD are therefore associated with impairment of these functions (Aguirre and Darling, 2012) (Box 1).

A cat suffering from CKD is likely to be experiencing both physical and emotional pain due to the number of side effects associated with the disease; vomiting, dehydration and anorexia for example. Pain can cause further complications as many of the negative side effects can lead to further deterioration and affect the patient's wellbeing.

Cats suffering from CKD will inevitably at some point undergo a period of hospitalisation diagnostic tests or to provide more intensive support such as fluid therapy. The nurse's role during this period is usually to assess food intake, monitor fluid therapy, take measurements of vital signs and conduct diagnostic tests as required. However none of these nursing interventions measure the cat's mental wellbeing, whether they are stressed and whether emotional support is adequate. The cat's behaviour is not assessed for indications of physical or emotional pain.

Physical pain management

In the last two decades the appreciation and understanding of physical pain in animals has developed significantly (Reid et al, 2013). It is now well established that animals have similar neural pathways as humans (Hellyer et al, 2007) and that they feel pain even if they do not have the ability to verbalise it (Grant, 2006). This has meant that the treatment and monitoring of pain has advanced notably in recent years.

However pain management has largely focussed on acute physical pain — the sensory side of pain (Flecknell, 2008). Pain management in cats has also fallen behind that of dogs, with the following being identified as the most common reasons for this:

Dohoo and Dohoo (1996) and Coleman and Slings-by's (2007) research also found that higher pain scores were given to dogs than cats and there is also the view that more empathy is felt for dogs because they express pain in a clearer way (O'Connor, 2011). Feline patients have developed survival techniques to prevent them from showing visible signs of pain and distress (Bryant, 2012); however pain can be observed through more subtle signs (Table 2).

| Behaviours to consider when assessing pain |

|---|

| Posture |

| Facial expression |

| Ability/willingness to move |

| Ability/willingness to use litter tray |

| Ability to lie down and sleep |

| Appetite |

| Demeanour |

| Mental status |

| Attention to wound |

| Vocalisation |

Physical pain in general is managed with pharmacological intervention but many pain relieving drugs can be harmful to kidneys; opioids can cause prolonged effects as they are cleared by the kidneys in urine and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can cause alterations in renal blood flow (Kipperman, 2012).

Traditionally pain was assessed by looking at physiological parameters such as increased heart rate respiratory rate, and blood pressure. These parameters will usually increase when an animal is in pain due to the stress response that pain causes. However more recently the use of pain scoring systems has meant that pain can be analysed using behaviour observations alongside physical observations.

Research suggests that the current use of pain scoring charts is still low (Coleman and Slingsby, 2007) however many veterinary nurses agree that they would be useful in the assessment process.

Emotional pain management

Currently there are no specific recommendations for evaluating emotional pain experienced in patients, however emotional pain, as physical pain, can alter a patient's behaviour and many of the behaviours displayed with both types of pain are similar (Table 2). It might be logical, therefore, to assume that a pain scoring system developed for assessing physical pain may also be of use to assess emotional pain. However this means that if emotional pain is detected methods of alleviating and managing it need highlighting to direct nursing care.

Three areas which should be considered in feline patients undergoing periods of hospitalisation are: the environment; the use of pheromones; and nursing care.

Environment

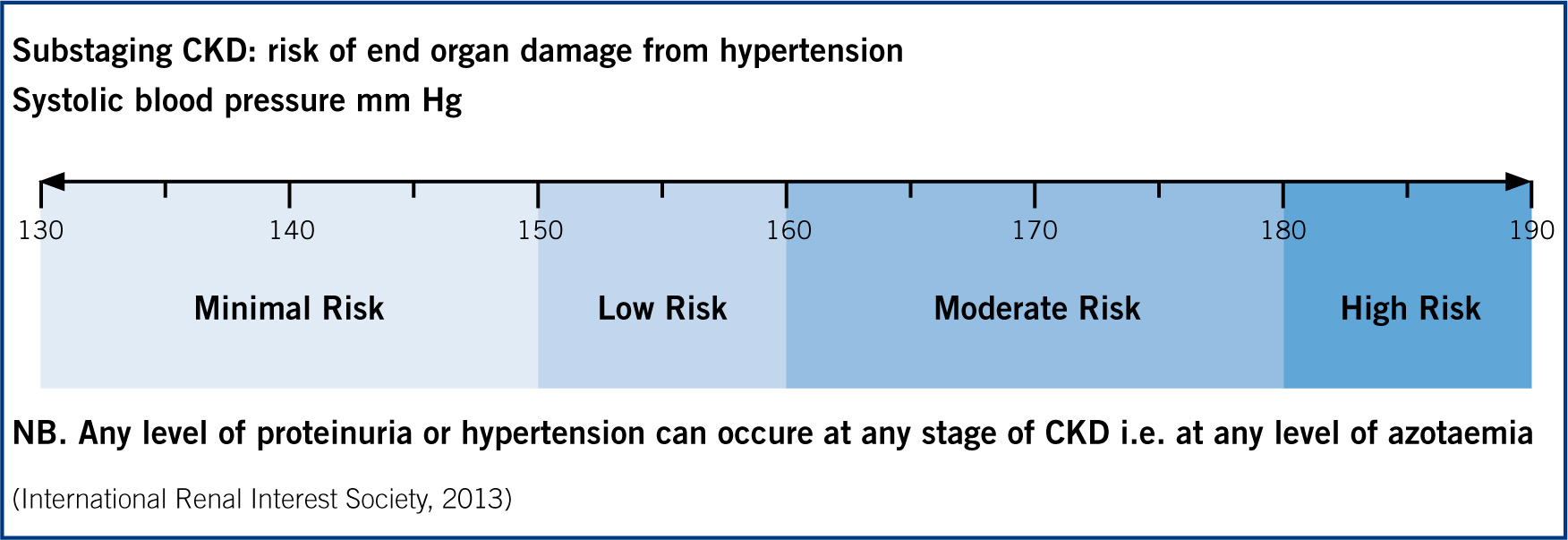

Cats by their very nature will feel distress when visiting the veterinary practice or during periods of hospitalisation as they are not a naturally social species and are highly territorial (Sparkes, 2013). Guidelines can be taken from schemes such as the Cat Friendly Clinic run by the International Society of Feline Medicine (ISFM) to try and make the veterinary environment less stressful for feline patients. Stress has the ability to increase heart rate, respiratory rate and blood pressure (Quimby et al, 2011). This is a particularly important consideration when assessing physical parameters of patients with CKD especially the increase in blood pressure. Raised blood pressure is one of the key indicators in staging kidney disease (Figure 1).

Higher blood pressure values therefore could be incorrectly assigned, being due to patient stress rather than the effects of the stage of kidney disease.

Research carried out in adoption centres concluded that cats who were offered enriched housing and were handled in a more positive consistent way by the same handlers received lower stress scores using The Cat Stress Score (Kessler and Turner, 1997) than those who were provided basic accommodation and handled by a variety of shelter staff in an inconsistent way (Gourkow and Frazer, 2006).

This was backed up by Kry and Casey's (2007) research which found that providing a hide improved cats' welfare and that cats provided with a hiding place were likely to show more affiliative behaviour. This was suggested to be due to the cat being able to display natural behaviour, therefore reducing stress levels. This study again was conducted in a shelter environment but provides confirmation that the environment can affect a cat's wellbeing, suggesting that during periods of hospitalisation environment should be an important consideration.

Hides such at the Feline Fort, which have been designed by the Cats Protection League (CPL) could be used for hospitalised patients to provide them with a place of retreat (Figures 2 and 3). However during the BSAVA conference (2013) a survey carried out by the CPL asking whether veterinary surgeries provided a hide for feline patients found that 60% of veterinary practices did not (Cats Protection League, 2013).

Pheromones

The use of feline pheromones in practice has grown and diffusers are often placed in cat wards and kennels are often sprayed with the aim of reducing acute stress on the patients (Mills, 2013).

Products such as Feliway (Ceva Animal Health) are a synthetic copy of the feline facial pheromone which is used by cats to mark their territory (Ceva, 2014). Use of facial pheromones is therefore intended to make cats feel more secure in the environment and help reduce the stress experienced in situations where they may feel threatened (Ceva, 2014).

Emotional pain and stress can be linked and cats suffering from CKD are likely to be under stress, especially during periods of hospitalisation. The use of pheromones may help during their time in the hospital environment (Pageat and Gaultier, 2003; Hellyer et al, 2007).

Nursing care

Good nursing care through accurate assessment and a systematic holistic approach can be an analgesic in itself (Kipperman, 2012). Thinking about the patient and spending time understanding their normal behaviour can help in assessing the care given and help indicate how effective that care is. Many would argue that of the veterinary personel the veterinary nurse is best placed to assess pain in patients. Nurses usually spend more time with patients than other members of the team and are able pick up on subtle changes in the patient's behaviour.

Providing tender loving care (TLC) for example can deliver immeasurable benefits — in humans it helps to decrease distress by reducing the pain/distress/sleepiness cycle which leads to a demoralised state (Lascelles and Waterman, 1997); this is also likely to be true in animals.

Most nurses would argue they provide TLC every day, however in a busy practice this element of nursing care often gets neglected. As long as the patient has received its medications at the correct time, food and water have been provided and the patient assessments have been made, the nurse's job is considered done, and often time is not allocated for the nurse to provide patients with emotional support. Stroking and touch therapy can have a positive impact on mood for example (Lindley, 2006).

Interaction with the patient should be positive and not all actions should be negative. The use of needles should also be kept to a minimum if possible and staff should be trained in using minimal restraint for procedures should as blood pressure readings (Pittari et al, 2009).

The focus of the care should be to restore comfort as it can greatly offset the unpleasant feeling associated with disease (Kerrigan, 2012). The veterinary nurse can help to improve the patient's emotional wellbeing by providing companionship, social interaction along with mental stimulation (Kerrigan, 2012).

Conclusion

Pain has a sensory and emotional element and this should also be considered when providing care to patients. Both types of pain have the ability to cause suffering and both have a behavioural element which can be assessed.

Pain scoring charts, although designed for use in assessing post-operative acute pain in cats, could be useful in focusing the nursing care delivered to a cat with CKD. Pain scoring is a useful tool to aid assessment and should form an integral part of the care given to all patients. Further work would be beneficial to create a tool to assess pain in non-surgical cases and to achieve validation in cats so there is a gold standard to work towards.

Veterinary nurses are best placed to provide care that not only focuses on the disease process but also encompasses the mental wellbeing of the patient. Education on how to use pain scoring charts to contribute to the nursing process would help establish this. Pain scoring charts specifically designed to assess physical and emotional pain in diseases such as CKD may contribute to assessment of the patient's quality of life in the latter stages of the disease; further work in this area would be beneficial.