Domesticated felines have been kept as pets throughout the centuries for many different reasons. Today the UK has an estimated population of 10.9 million cats (PDSA, 2020), and maintaining their nutritional and health needs is extremely important to ensure they live a happy and healthy life. The World Health Organisation (WHO) describes nutrition as ‘the intake of food, considered in relation to the body's dietary needs,’ with good nutrition being described as a ‘well balanced diet combined with regular physical activity’ (WHO, 2021).

The nutritional needs of felines

Domestic felines require specific dietary components in comparison to domestic canines. Felines are obligate carnivores; a term which defines their inability to synthesise vitamin A, arachidonic acid and taurine, meaning they require a dietary source of these obtained only from animal protein. Taurine is a sulfonic acid abundant in the natural food of felines, such as small rodents and birds, and is abundant in animal tissues but absent in plants, hence vegetarian diets are not suitable for cats. See Table 1 for comparison and reasoning.

Table 1. The nutritional needs of cats — comparison and reasoning

| Nutritional need of feline | Reasoning | Nutritional need of canine | Reasoning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intake of external taurine (Sanderson, 2013) | Taurine deficiency can lead to retinal damage, cardiac disease, growth issues and low fertility (Royal Canin, 2006) | Non obligate carnivores | |

| Higher quantities of fat and protein (Sanderson, 2013) | Failure to provide nutrients correctly could lead to

|

Comparatively lower or higher levels of niacin/B6 | |

| Amino acid arginine and vitamins Niacin and B6 (Sanderson, 2013) | Reduced immunity Increased susceptibility to disease Reduced productivity Impaired physical and mental health | ||

Further resources for nutritional guidelines and full listing of exact values of components required can be found at the following resources listed in the Bibliography:

|

|||

In addition to ensuring these nutrients are provided, it is also imperative to ensure that the specific and unique requirements of felines are tailored to with regards to assisted feeding techniques. As they are prey animals, they traditionally do not like to eat in view of other animals. They often prefer shallow, small dishes for nutritional intake because of the importance of their whiskers in both balance and exploring the spaces around them. These simple resources and techniques are often overlooked, but factors such as timing, location, method and amount of feeding must be considered, for example not placing bowls near to washing machines or thoroughfares for human traffic (Chandler and Takashima, 2014). Furthermore, when considering the provision of nutritional intake, stress factors must also be considered. When encountered in hospitalised patients, stress is often counterproductive to maintaining a good body condition score (BCS). This is often because of enhanced glucogenesis by animals that are either ill and/or injured, that will often mobilise protein because of alteration in hormones in times of stress (Brunetto et al, 2010). Deciding which route to take can often be challenging for the veterinary professional. Table 2 details a basic overview of the metabolic differences between simple and stressed starvation in relation to metabolic reactions.

Table 2. Metabolic differences between simple and stressed starvation Barendregt et al, 2008

| Simple starvation | Stressed starvation |

|---|---|

Shorter periods =

|

Occurs not only due to starvation but when also exposed to metabolic response to trauma, sepsis and clinical illnessNormal responses overridden by neuroendocrine and cytokine effects of injuryResult =

|

Initial steps should be taken at 1–2 days of hospitalisation to assess nutritional needs, write food orders and monitor nutritional intake when formulating the choice of foods for each particular patient (WSAVA, Global Nutrition Committee (GNC), 2013). The WSAVA nutrition guidelines further go on to describe the assessment and evaluation of dietary needs. Each animal should be reassessed daily to determine the optimum route for feeding, whether that be oral feeding, syringe feeding or tube feeding (Freeman et al, 2011). Constant and ongoing nutritional assessment and evaluation is especially important in sick and hospitalised felines. These cases are often overlooked as the need is felt to stabilise their condition prior to nutritional intervention, however these cases are most at risk from malnourishment and concerns, such as insulin resistance, muscle wastage, poor immune system function, delayed wound healing and hepatic lipidosis (Bolton, 2017).

Which foods are best?

Initial stabilisation of the patient should always be the primary step, including under the veterinary surgeon's direction administration of any pain relief, starting fluid therapy, and scheduling any further medications or imaging. Key nutritional factors of a feline diet are indicated in Tables 1 and 3. Once the patient is stable enough to initiate even simple methods of assisted feeding such as hand feeding, the nutritional components, including the macro-nutritional components, must be examined in close detail (Villaverde and Fascetti, 2014). Broadly speaking, approximately 60–70% of the immune system function of both cats and dogs takes place in the intestine, and the intestinal structure or mucosa must remain intact for proper immune development (Corbee and Van Kerkhoven, 2014). Regardless of the nature of the patient illness being treated, the first 14 days after trauma or onset of illness is of primary importance for the correct absorption of fluids, essential nutrients and energy (Corbee and Van Kerkhoven, 2014), and the choice of which diet to use must be made on the basis of both the scenario in question and the composition and contents of the foods available. Following initial injury, if there is a wound present the body will start to initiate the inflammatory and healing process of haematosis, inflammation, proliferation and maturation. Platelets will adhere to the site of injury with white blood cells aiding the healing process. All cells need appropriate energy and glucose levels to function and perform their role adequately. Without these components, healing can be impaired as a result of poor cell function.

Table 3. Change in biological processes simple vs stress starvation Barendregt et al, 2008

| Biological process | Change in simple starvation (>72 hours) | Change in stress starvation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increased | Decreased | Increased | Decreased | |

| Metabolic rate | ||||

| Protein catabolism (relatively) | ||||

| Protein synthesis (relatively) | ||||

| Protein turnover | ||||

| Nitrogen balance | ||||

| Gluconeogenesis | ||||

| Ketosis | No change | |||

| Glucose turnover | ||||

| Blood glucose | ||||

| Salt and water retention | ||||

| Plasma albumin | No change |

Omega-3 fatty acids, particularly long chain polyunsaturated acids, and prebiotics as well as taurine, arginine and vitamins niacin and B6 (pyridoxine), can help to shorten the recovery period and promote optimal wound healing (O'Dwyer, 2017). The first 14 days of recovery following trauma are essential to provide these nutrients and ensure correct functioning of both the gastrointestinal and immune systems. Functioning of white blood cells and neutrophils to help stem and fight off infection require adequate nutrition and glucose to remain functional (O'Dwyer, 2017).

Additional components for maintaining both wound healing and the overall recovery of the patient include macro-nutritional components, the main ones being protein, fat and carbohydrates. As well as providing the energy requirements needed for hospitalised patients, a high loss of lean body mass may well result in lower overall energy expenditure and hence predispose animals to weight gain (Villaverde and Fascetti, 2014).

If a tube is required to be placed, the appropriate measures and monitoring of nutritional intake can be initiated. Dependent on the type of tube placed, if this is the case, the most appropriate diets to use, especially for oesophagostomy (O) tube feeding are specially formulated diets, such as Royal Canin Convalescence Support diet or Purina Veterinary Diets, which can also be used for nasogastric (NG) tube feeding. These specially formulated diets are designed to fulfil the patient's needs, and can be easily prepared for feeding via a tube with the addition of warm water when weighed out according to manufacturers' guidelines. The Royal Canin convalescence diet is useful as a diet for hospitalised patients that require tube feeding because of the components and composition of the diet. An increased protein level helps to provide the energy required for restoration of lean body mass, and an increased energy concentration enables smaller volumes to be consumed while ensuring a reduced workload for the intestines. The addition of an antioxidant complex, such as taurine, helps to neutralise free radicals and helps to support the health of cells. Commercially canned diets can also be used, however the lumen diameter of the tube should always be taken into consideration and information taken from the below reference indicates that no more than 10 ml of food should be administered at one time. As a general rule, it is considered that a volume of no more than 10 ml/kg (including water used to flush the tube) should be used (All Feline Hospital, n.d.; Hodshon and Tobias, 2014). If tubes get blocked, they can be unblocked by flushing them with water — and regular flushing can help keep them unblocked. The tube should always be flushed prior to dietary administration with approximately 12 ml of water to facilitate easier administration, and also to check the tube for any signs of displacement (All Feline Hospital, n.d.; Hodshon and Tobias, 2014).

The diet chosen to provide nutrition during assisted feeding must be sufficient to maintain lean body mass, and must be able to provide the resting energy requirement (RER) to allow for the correct number of kilocalories (Kcal) per day (WSAVA, 2013).

Furthermore, it is also important to ensure that hydration levels and blood pressure are stable before initiating the intervention of assisted feeding (Freeman, 2015).

When and how should feeding be carried out?

The exact timings and specificities of when assisted feeding should be carried out should be based on a number of factors. External and intrinsic factors such as stress, nausea and pain must first be addressed and controlled (Taylor and Korman, 2014), and then simple methods of assisted feeding could first be trialled based on each individual case. Simple barriers to reduced dietary intake include the type of food bowl used, the temperature of the food and the type of food, and are often factors that can cause food aversion (Taylor and Korman, 2014).

Feeding techniques — enteral

Enteral nutrition utilises a functioning gastrointestinal tract and can be provided through either a naso-oesophageal (NO) (Figure 1) or O tube (Figure 2) (Table 4). NO tubes can be placed without a general anaesthetic in tolerant patients, however they are often limited by the fact that few diets are able to pass through the thin lumen of the tube (Taylor and Korman, 2014; Frye et al, 2015). For patients where food aversion has become an issue because of syringe or simple hand feeding, where a novel diet has been introduced during illness, or where there is some sort of barrier to being able to provide oral provision of nutrients, enteral nutrition is the best route available to the veterinary field (Taylor and Korman, 2014; Frye et al, 2015).

Table 4. Comparison of enteral feeding tube routes

| Tube | Indications | Requirement for general anaesthetic | Minimum/maximum length | Period of placement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NG tube | Where short term (7–10 days) assisted feeding is requiredFunctional oesophagous, stomach and small intestine required | No | Range from 4 French to 10 French | Short term |

| O tube | Nasal, oral or pharyngeal disease | Yes | 12 to 14 French | Weeks to months |

| Gastrotomy tube | If contraindications for entral feeding such as severe vomiting or ileus | Yes | 20 to 24 French | Long term |

| Jejunostomy | When vomiting is a persistent clinical sign | Yes | 5, 8 or 10 French |

O tubes are often used in veterinary practice. They are also known as esophagostomy (E) tubes, and can be used for short- or long-term feeding.

On a practical basis, O tubes are suitable for use in patients with a healthy, functioning and unobstructed gastrointestinal tract. They can be placed quickly and easily under general anaesthesia, and have a suitably large diameter to allow for feeding of larger particles (Figure 3) (Schoor, 2015). Cats should be fed >6 g of protein per 100 kcal, regardless of life stage or health status. Recovery diets including Royal Canin Recovery, Hill's A/D or Hill's feline i/d meet these recommendations and are easily available. Diets may need to be blenderised or diluted, dependending on the size of the tube used (Schoor, 2015).

Feeding techniques — parenteral

Parenteral nutrition is typically used only as a last resort because of the increased risk of complications and infection. It is used to administer nutrition and describes the administration of nutrients via a route other than that of the gastrointestinal tract, usually via the bloodstream, and is typically discussed as either total or partial parenteral nutrition. Typically, parenteral nutrition should be used with animals that have gastrointestinal dysfunction, or in animals whereby enteral nutrition may have an increased risk of aspiration (Baldwin et al, 2010). Parenteral nutrition can further be divided into total and partial parenteral nutrition, and commercially available products can be used.

Total parenteral nutrition

Total parenteral nutrition is indicated in generally debilitated animals, where the gastrointstinal tract is not functioning adequately. This would be in cases such as prolonged ileus and malassimilation (Raisis, 2007). The products used for this are hyperosmolar, and therefore the concentration is unsuitable for administration via a peripheral vein, so are generally administered using the jugular vein (Chandler, 2012). The use of total parenteral nutrition in feline patients was evaluated to determine both the frequency of complications and the risk factors for any complications. The complications were categorised into a number of factors. The most common complication was hyperglycaemia. There was an increased risk of this in cats provided with energy above the RER (Crabb et al, 2006). Further evidence indicated that while useful for providing the energy needs required by the patient, the risk of mechanical complications was less when the catheter was placed in the jugular vein compared with the saphenous vein. They are also generally less accessible to the patient, so reduce the chances of complications caused by patient interference (Queau et al, 2011).

Partial parenteral nutrition

Partial parenteral nutrition describes the provision of nutrients intravenously for animals that are unable to tolerate enteral nutrition (Chan et al, 2002). Partial parenteral nutrition is sometimes referred to as peripheral parenteral nutrition, and can be administered via a peripheral vein, this differs from total parenteral nutrition, which is administered through a central jugular vein (Chan et al, 2002). A retrospective study conducted through examination of medical records evaluated and characterised the use of partial parenteral nutrition in dogs and cats. Records were evaluated and examined to determine signalment, reasons for use, duration of administration, hospitalisation, complications and mortality. The study determined that the most common complications were metabolic, including lipaemia, hyperbilirubinaemia and azotaemia, however the risk of metabolic complications was less than has been previously reported in animals receiving total parenteral nutrition (Chan et al, 2002).

Appetite stimulants

Once nutritional supplementation is in place and the patient is receiving a sufficient amount of nutrients on a daily basis, appetite stimulants can also be introduced as part of the treatment plan. They should, however, only be used as an adjunct to treatment and not as a substitute for treating the underlying complaint.

Appetite stimulants are often used to overcome food aversion and to induce appetite stimulation on a short-term basis. Common stimulants used include mirtazapine (an eighth to a quarter of a 15 mg tablet every 1–3 days orally). A dose rate 1.88 mg is recommended as the initial starting dose for oral mirtazapine and can be given as frequently as daily in young normal cats (Quimby, 2020). Also, diazepam (intravenous (IV)) at 0.2 mg/kg, has been discussed, although this should be avoided orally because of the possible idiosyncratic reaction and is generally only useful IV as an immediate appetite stimulant (Taylor and Korman, 2014). It has also been shown to cause and exacerbate liver issues (Brooks, 2013).

Mirtazapine has been used in both the USA and UK for around 10 years, however research has shown that caution should be exercised when using this drug in cats, as higher doses can result in an increased risk of side effects such as lethargy, gastrointestinal signs and cardiovascular signs (Ferguson et al, 2016).

Cyproheptadine is commonly cited as an appetite stimulant that can be used in veterinary practice, however it is a drug typically used to reduce serotonin uptake with a common side effect of stimulating appetite (petmd, 2015). It can be used in cats that have developed serotonin syndrome consistent with mirtazapine toxicity (Ferguson et al, 2016).

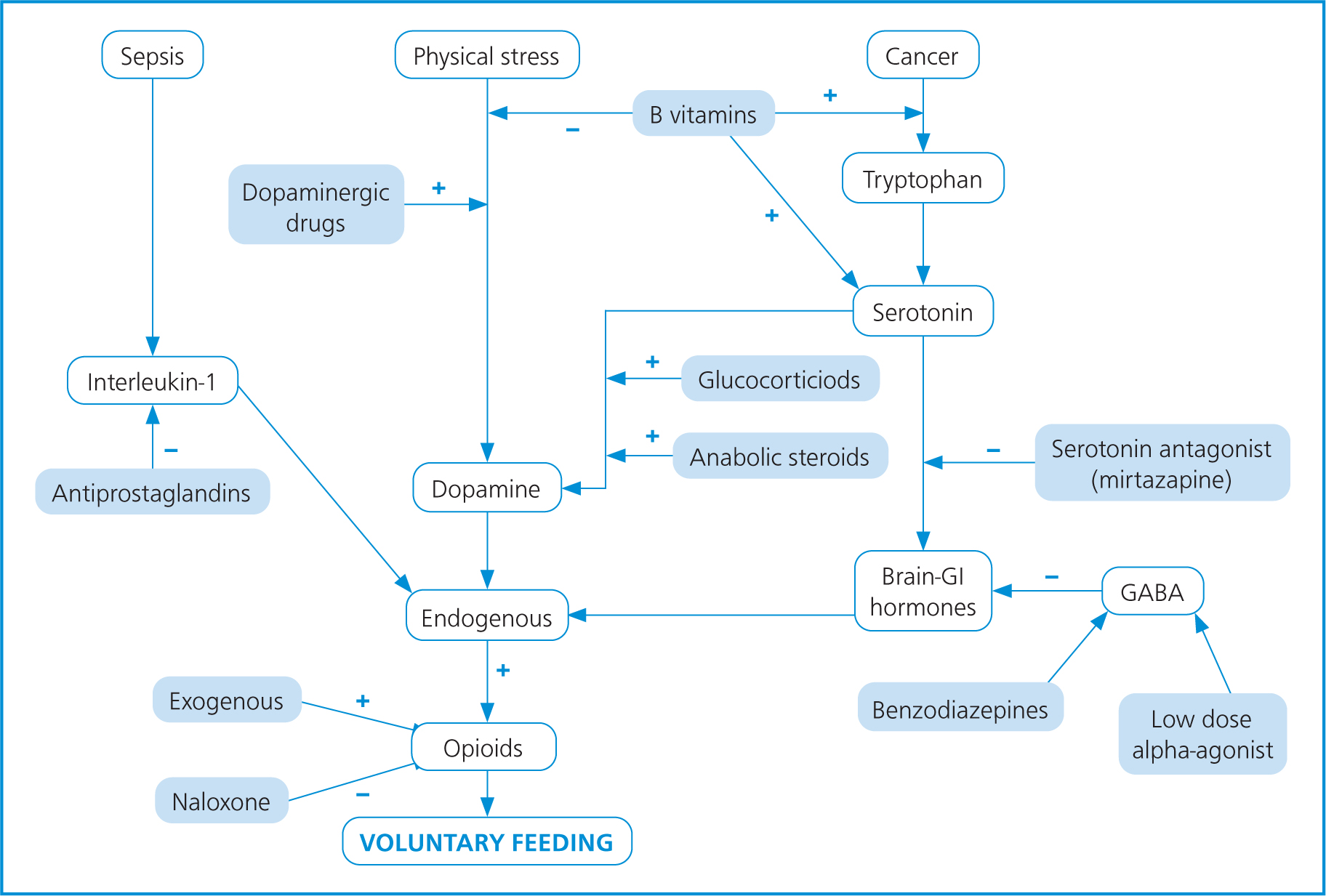

Appetite stimulants should be used only as a last resort and are generally not effective in very ill patients. They should only be considered in cases such as supporting nutritional intake in chronically ill cats or for short-term use in the diagnostic phase (Agnew and Korman, 2014). Figure 4 shows the various interactions of substances and factors which affect appetite regulation, and how these can affect the type of feeding and choice of drugs used. Please note, however, that exact dose and choice of drugs, including the instigation of any general anaesthetic for placement of a tube, is the remit of the veterinary surgeon.

Several studies from Quimby evaluated the use of appetite stimulants, especially in renal disease in felines (Quimby, 2020; Quimby and Lunn, 2013; Quimby et al, 2011). Renal disease typically presents with polyuria, polydipsia, decreased appetite, weight loss and vomiting. Typically, treatments involve medical management of these symptoms with management and monitoring of possible metabolic complications (Quimby and Lunn, 2013).

Cyproheptadine can be used as an appetite stimulant; however, mirtazapine is frequently used in the veterinary profession. It is not specifically a medication created for use as an appetite stimulant. Mirtazapine is a human drug used as an antidepressant; however, it has application in the veterinary profession because of its anti-nausea, antiemetic and appetite stimulating properties (Quimby and Lunn, 2013). One study conducted by Quimby et al (2011), used six stable chronic kidney disease cats owned by clients and six geriatric control cats to assess the pharmacokinetics of mirtazapine in chronic kidney disease. It concluded that chronic kidney disease delays the clearance of mirtazapine, however a previous dose of 1.88 mg had been shown to have an effect. There is a potential for accumulation with daily dosing of mirtazapine, however no evidence of drug accumulation was seen within the 48-hour dose interval.

Conclusion

Whenever a patient is admitted to the hospital environment, nutrition should be included as part of the initial assessment as well as the nursing care. Care should be taken to avoid stress in the patient, and induce the most accurate home environment possible. An up to date, accurate and concise feeding plan should be in place for each patient, tailored to their individual needs. Appetite stimulants can be used, however, it is important to remember that this should be done only as a last resort and efforts should be taken to investigate and pinpoint the cause of any inappetence. If assisted feeding is introduced, then the enteral route should be utilised unless there is a valid reason not to. Expertise, the patient's needs, and the client's needs should be taken into consideration before proceeding with an ongoing plan.

KEY POINTS

- Early nutrition in hospitalised patients ultimately leads to a quicker recovery.

- Simple techniques for providing nutrition should and can be initiated in the early stages, however this must not prevent more in-depth nutritional intervention taking place if needed.

- Felines have specific nutritional requirements that differentiate them from other species.