With more owners choosing routine veterinary care, which allows for early detection and treatment of illnesses and diseases, it is becoming increasingly common to see geriatric rabbits in the veterinary practice. As pets age, special considerations are taken in regard to nutritional needs, comfort level, health status, and quality of life (Figure 1). Veterinary nurses play a key role in educating clients on the special needs of these patients. In the past, the average lifespan for domestic pet rabbits was considered 5 to 7 years (Meredith and Lord, 2014). Improved quality of care, ideal diets, routine veterinary visits, and elective altering are thought to be associated with increased lifespan, in some individuals as old as 10–14 years (Harcourt-Brown, 2002). The authors consider rabbits to be geriatric starting at 7 years of age.

General nutrition

The ideal diet for pet rabbits is unlimited grass-based hay, green leafy vegetables, and limited high-quality, hay-based pellets (Bradley, 2004). As they age, geriatric rabbits are fed the same foods, with proportions and amounts adjusted based on condition. If the geriatric patient is sedentary or not active and burning calories, which can lead to weight gain, it may require less pellets and more hay. Generally, rabbits should be fed 1/8–1/4 cup of hay-based pellets per day or as per package instructions (Mayer and Donnelly, 2012). If the patient is experiencing muscle wasting, more pellets and the addition of alfalfa hay may help maintain weight (Lennox, 2010).

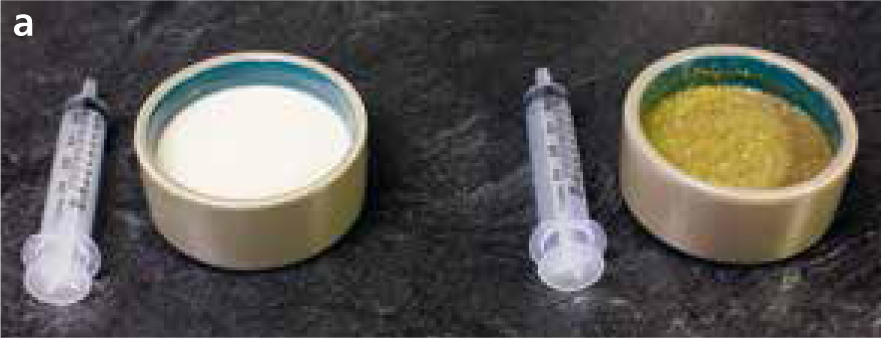

Patients with decreasing appetite for any reason may benefit from additional nutritional support in the form of commercial hand-feeding formulas offered via a syringe or bowl (Figure 2a and 2b) to increase caloric intake and support gastrointestinal (GI) health (Lennox, 2010). Companies like Oxbow and Lafeber make such formulas.

Some owners may inquire about supplements for their rabbits. A few companies offer supplements for older rabbits (Figure 3). While there is little scientific evidence-based medicine for the benefit of supplements, some owners see benefit for such products, e.g. joint support supplements containing ingredients such as glucosamine, turmeric powder, and ginger root can be given to help reduce inflammation (Tiraloche et al, 2005).

All rabbits require a higher volume of water intake than other companion animals (Quesenberry et al, 2003). Adequate hydration is important to aid ageing kidneys, as chronic renal disease is common in older rabbits. If the patient is not taking in adequate amounts of fluids this can slow and damage kidney function (Mayer and Donnelly, 2012). Ways to increase fluid intake include offering both a water crock and bottle (Figure 4), increasing the amount of greens as tolerated, and soaking greens in water prior to feeding (Figure 5).

Housing and environment

Rabbits experience varying levels of disability as they age. Decreased vision may make abrupt changes in the cage or hutch stressful and confusing; for these pets it is important to keep the location of the food, litter box, and hide spots consistent. Rabbits with mobility issues benefit from anti-skid mats over any slippery surface. Cutting out one side of the litter box makes access easier (Figure 6). Ramps may aid older rabbits who still enjoy moving from level to level.

Common medical conditions in geriatric rabbits

Renal insufficiency

Many disease processes can damage the kidneys, including toxins, infections, urolithiasis, and any disease resulting in chronic dehydration (Lennox, 2010; Harcourt-Brown, 2013). In some cases, the actual cause of kidney disease may not be known.

Diagnostic work up (blood work and diagnostic imaging such as radiographs and ultrasound), and treatments (fluid therapy and treatment for specific underlying disorders such as urolithiasis), is similar to that in other domestic pets. The authors typically sedate rabbits for diagnostic work-ups; sedation calms the patient and makes procedures less stressful for both the patient and the veterinary nurse. If a geriatric patient has stiff or painful joints, sedation will help relax the patient and make the experience less stressful while manipulating the joints for a blood draw and radiographs. In the US, radiographs are taken with the veterinary nurse restraining the patient while the patient is sedated (Figure 7). The veterinary nurse must wear proper personal protection equipment (PPE) to reduce exposure to radiation. Sedation also helps the diagnostic work-up process go smoothly so that it can be done efficiently and with the least amount of physical restraint required. When sedating a patient for a work-up, the veterinarian should prepare a drug protocol for the patient. For sedation, the authors use: midazolam and hydromorphone, with additional drugs such as alfaxalone and dexmedetomidine if needed.

Keeping the patient hydrated is extremely important in chronic renal insufficiency patients. When a skin turgor test is performed, keep in mind that geriatric patients often have thickened skin, or skin that is loose secondary to marked weight loss, and can therefore present a false dehydrated status (Figure 8). Blood work can provide supporting evidence for dehydration. Hydration may be maintained via several routes depending on diagnosis and severity: intravenous fluids; subcutaneous fluids (Figure 9); hand feeding with a reconstituted nutritional support supplement; offering wetted greens; and providing a water bottle and water crock. Those needing long-term fluids at home may use a GIF-tube (as sold by Patterson Veterinary) placed subcutaneously, which allows owners to administer subcutaneous fluids at home without needles.

Cardiac disease

Cardiac disease is reported in rabbits, and in most cases is diagnosed when the rabbit is in cardiac failure. Rabbits often present with varying degrees of increased respiratory rate and effort (Harcourt-Brown, 2002; Lennox, 2010). Owners may also often note symptoms such as hindlimb or generalised weakness, exercise intolerance, and weight loss. On presentation, pallor, tachycardia, muffled heart sounds, cyanosis, heart murmur, arrhythmias and crackles may be observed (Mayer and Donnelly, 2012). Diagnostics to confirm cardiac disease include radiographs and echocardiogram. Care must be taken during handling of the cardiac patient, especially when attempting venepuncture or positioning for radiographs. Sedation of a geriatric patient is extremely beneficial and discussed in more detail below. When using sedation only for radiographs on geriatric rabbits, which is common in the US, obtaining a dorsoventral rather than a ventrodorsal radiograph is less stressful and will cause less discomfort while manipulating joints (Lord et al, 2011).

Mobility issues

Mobility complications are one of the most common issues for geriatric rabbits; rabbits may become less mobile due to pain or lethargy. Painful rabbits often groom less or not at all, resulting in urine and faeces accumulation around the perineum and a rough ungroomed coat. Other medical issues such as dental disease and obesity can lead to an ungroomed perineal area (Figures 10 and 11).

Decreased mobility is also associated with pressure sores, pododermatitis, obesity, muscle atrophy, and bladder sludge, or the accumulation of microuroliths in the bladder (Meredith and Lord, 2014). Normal ambulation causes minerals in the urine to mix and suspend; it is thought that long periods of inactivity cause minerals to accumulate in the ventral bladder while liquid urine is eliminated, resulting in thicker, more dense urine that is difficult to void (Figure 12). Large accumulations of sludge appear to be uncomfortable and are associated with urine dribbling and scalding (Lennox, 2010).

Modifications of the environment to benefit rabbits with decreased mobility are discussed above. Rabbits with severe mobility issues, that are unable to use a litter box, can be maintained on absorbent padding that is changed frequently, with careful attention to hygiene of the perineum.

Geriatric rabbits benefit from routine grooming of their perineal area to avoid matting and accumulations of faeces and urine. Regular complete shaving of the perineal area may greatly enhance the ability of owners to keep this area clean (Figure 13).

Underlying disease conditions should be identified and treated in these patients. Some geriatric rabbits may benefit from long-term pain management, which most often includes NSAIDs and, in some cases, opioids (Barter, 2011). Alternate modalities such as laser therapy and acupuncture have been described in rabbits as well (Gaynor and Muir, 2015).

Special considerations for handling for diagnostic testing and anaesthesia

Sedation is extremely beneficial to help reduce patient stress and struggling during handling and diagnostic testing. The authors prefer midazolam 0.50 mg/kg combined with an opioid. The drugs are combined into a single syringe and administered intramuscularly (IM) in order to reduce stress and handling. After injection, allow the patient to rest comfortably for 5 to 10 minutes prior to handling. When drawing blood from older, potentially arthritic patients, take care to gently manipulate the limbs (Figure 14).

Geriatric patients with known or suspected renal or cardiac disease require extreme care when administering anaesthesia. Patients with mild underlying renal disease can experience acute renal failure if anaesthesia or a surgical procedure causes decreased blood pressure leading to hypoperfusion of the kidney.

Stress-free handling, a balanced anaesthetic protocol (combination of pre-medications, induction and maintenance agents), avoidance of drugs known to strongly affect blood pressure or to raise cardiac rate, careful monitoring, and intravenous (IV) fluid therapy before, during and after anaesthesia, can improve outcomes.

Euthanasia

Determining quality of life of prey species can be especially difficult due to their natural instinct to hide signs of illness. A quality of life scale will aid clients in decision making. Once a client has decided it is time for euthanasia, it is important to keep communication clear and nonintrusive. Discuss each step of the process and answer any questions the client may have. Confirm with the client whether they want to be present for part of the process, the entire process, or would prefer to visit beforehand and not be present for euthanasia at all. Take care of all charges, paperwork, and body care decisions prior to euthanasia to allow clients to focus solely on their pet once the process begins.

The euthanasia process should be as painless and stress free as possible for both the patient and the client (Box 1). In dogs and cats, the most common method of euthanasia is an IV injection of pentobarbital. This method is not recommended for rabbits and smaller exotic pets, as IV administration is more challenging (an exception is for a patient where IV or intraosseous (IO) catheterisation has already been established for an earlier procedure). The authors find that placing an IV catheter is time consuming and stressful for the patient. For euthanasia, administer a combination of anti-anxiety, analgesics, and anaesthetics by simple IM injection. IM injections cause only minor and brief discomfort and can be performed in front of the owner without distress to the patient or owner. The patient then can fall asleep peacefully in the owner's arms within 5–10 minutes (Figure 15). The authors prefer a combination of midazolam, an opioid, ketamine and medetomidine/dexmedetomidine at high enough dosages to induce complete anaesthesia. Once the patient is completely anesthetised and no longer responding to stimuli, pentobarbital can be humanely administered IV, intracardiac (IC), or intraperitoneal (IP) (McLaughlin and Strunk, 2016).

Some owners ask whether or not their pet's bonded companion rabbit should be present for the euthanasia or to view the body after death. The benefits of this are unclear. The authors prefer not to have the bonded companion present for the actual euthanasia, which can be distracting for all involved. However, many owners seem comforted by the thought of providing closure for the bonded companion, and the authors have seen no disadvantages or poor outcomes from this practice.

Conclusion

With proper care, starting at the beginning of the rabbit's life and to the end, rabbits can live long, healthy lives. Ensuring that geriatric rabbits are screened for underlying diseases and provided with proper husbandry and care at home are key steps to providing optimal quality of life for the rabbit's last years.