Canine dermatological disorders are recognized by veterinary surgeons to be a major problem in small animal practice, with an estimated 15–30% of the dog population worldwide affected by skin conditions (Scott et al, 2001). Many skin condition are associated with pruritus and this is one of the most common reasons for visiting a veterinary practice (personal observation). Itching is upsetting for both the dog and the owner. An itch is an unpleasant sensation of the skin which produces the desire to scratch. While it is possible to suppress a reaction to pain, it is almost impossible to ignore an itch.

Pruritus can be elicited with many skin conditions. A practical diagnostic approach is required to establish the cause of the pruritus. In doing so, it is important to appreciate the phenomenon of ‘pruritic threshold’. This is the level of stimuli that will induce itching in an individual, and this can vary between individuals. Various skin problems can combine stimuli to exceed this threshold resulting in varied severities of itch.

This article looks at how a systematic approach can help with making a diagnosis and the role that can be played by the veterinary nurse.

Diagnostic plan

History

Good history taking followed by a thorough physical examination and appropriate diagnostic tests is necessary to diagnose the cause of pruritus in each case.

History taking by the veterinary nurse should include:

Breed

Certain breeds are more prone to atopic dermatitis, such as terriers (Westies, Fox Terriers, Cairns, Scotties and Staffies), Labradors and Golden Retrievers, Dalmations, Boxers, English Setters, Shar Peis and German Shepherds. Other breeds can be affected and this list can vary with geographical variations in populations. Food hypersensitivity can be seen more frequently in German Shepherds, Labradors, Shar Peis and Cocker Spaniels. Malassezia dermatitis is seen more frequently in breeds like Basset Hounds, while demodicosis is relatively more common in Westies, often in conjunction with atopic dermatitis (personal observation).

Age

The age of onset of signs is a good diagnostic indicator. Atopy generally begins between 6 months and 3 years of age, occurring rarely to in animals less than 6 months of age. The onset of pruritus for the first time in older animals would suggest a metabolic, endocrine, or neoplastic aetiology was more likely (Scott et al, 2001).

Seasonality

A seasonal incidence would suggest atopy or ectoparastism (Scott et al, 2001).

Pet's living conditions

Contagious diseases such as scabies, dermatophytosis, fleas, and cheyletiellosis could affect in-contact people or animals. Contact with wildlife may suggest fleas, scabies or dermatophytes as a cause (Scott et al, 2001).

Diet

As well as a dermatological history, a general health history should be taken noting signs like polydipsia, polyuria, appetite, lethargy and gastrointestinal signs. Gastrointestinal signs are often associated with food reactions.

Severity of pruritus

It is useful to ask the owner to score the dog's itch on an appropriate scale, e.g. 1–10. This is helpful because some conditions are more pruritic than others. It can also be used later to assess response to treatment.

Medication history

A careful record of any medication the dog is currently or has previously been on should be noted. These may be involved in the pruritus, but it is also important to know if any of these medications have been prescribed for an ongoing pruritus and what the response has been. A poor response to steroids could suggest scabies, pyoderma or a food allergy, whereas uncomplicated atopy is described as a steroid-responsive disease (Scott et al, 2001).

Physical examination

Following a thorough history taking, a physical examination should be performed of the skin and other body systems. Distribution and nature of lesions can be very helpful indicators of the cause of pruritus: lesions around the dorsal rear quadrant would suggest a flea allergic dermatitis; involvement of the elbows and pinnal edges would suggest scabies; scaling on the dorsum would suggest cheyletiellosis; while lesions involving the feet, carpal flexures, axillae, face and ears would indicate atopy. The lesion type may help in diagnosis, e.g. pustules in pyoderma, pemphigus folliaceous and papules in ectoparasite disease and hypersensitivity. The lack of lesions would be indicative of uncomplicated early atopic dermatitis. There are many causes of pruritus (Table 1).

| Ectoparasites | Hypersensitivity | Infectious | Miscellaneous |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fleas | Flea allergy dermatosis | Pyoderma | Neoplasia, e.g. Epitheliotropic lymphoma |

| Sarcoptes scabiei | Atopic dermatitis | Dermatophytosis | Contact irritant |

| Cheyletiella | Food allergy/intolerance | Malassezia | Pyotraumatic Dermatitis (hot spot) |

| Neotrombiculosis (harvest mites) | Contact | ||

| Pediculosis (lice) | Insect hypersensitivity | ||

| Otodectes (ear mites) | |||

| Demodex |

Diagnostic tests

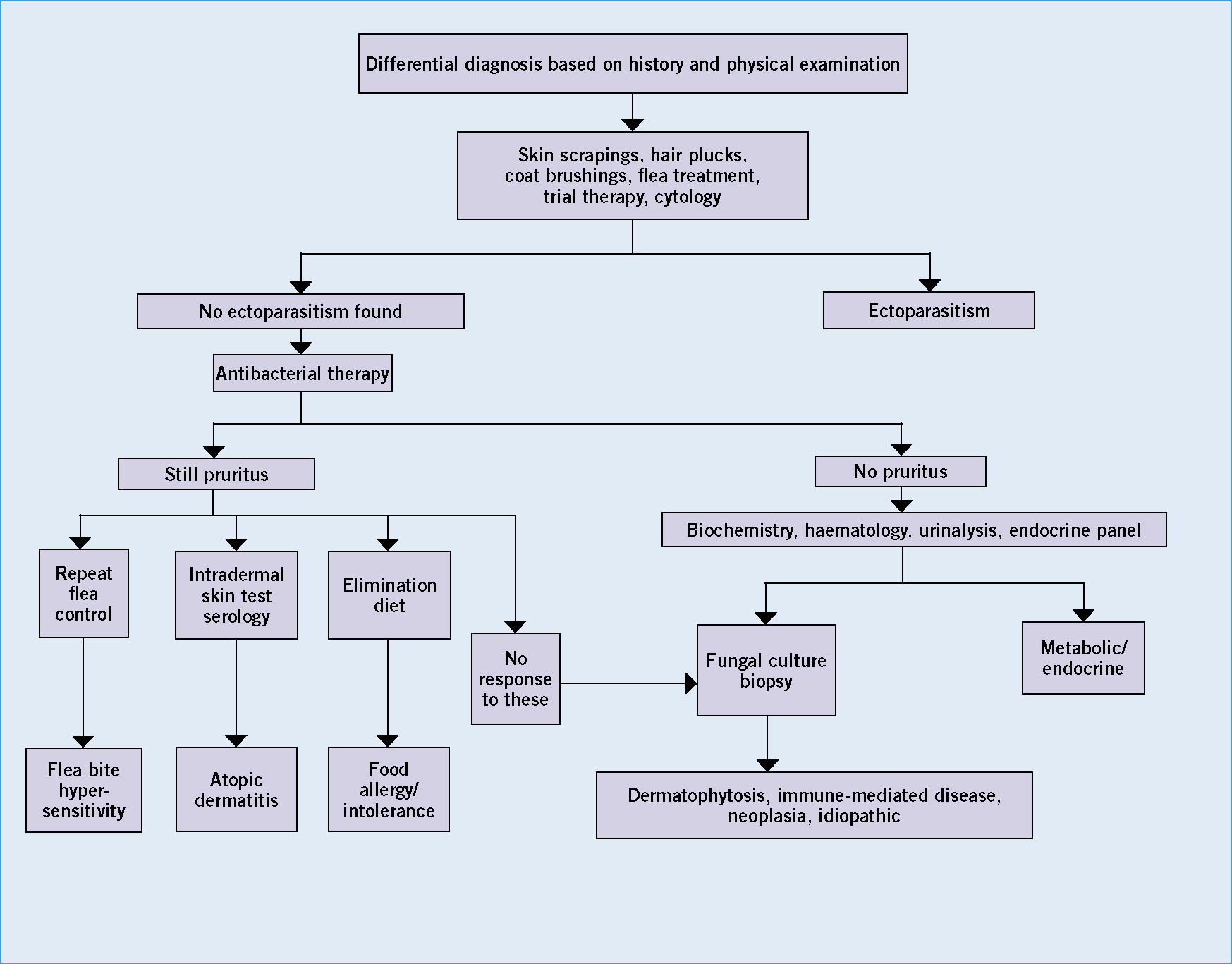

Once a careful history recording and physical examination has been performed a variety of diagnostic tests are used to aid diagnosis. It is useful to have an ordered sequence of steps to proceed in investigating. An algorithm may be helpful in reaching a diagnosis (Figure 1).

Initial diagnostic tests that can be performed by veterinary nurses should include skin scrapings (for detection of parasites and fungal infected hair), hair plucks (Box 1), and coat brushings. Samples can be taken for cytology to be performed by the veterinary surgeon.

Following these initial tests, haematology and biochemistry profiles may indicate systemic disease, and possibly endocrine disease with endocrine panels. Bacterial and fungal culture can identify infectious agents, being careful to avoid contaminating samples.

Hypersensitivity testing

Investigation of hypersensitivity disorders is being carried out more frequently by veterinary nurses in practice. Identification of relevant allergens can be pursued using intradermal skin testing or serology. Intradermal skin testing kits can be purchased from various sources such as ARTU Biologicals (Lelystad, The Netherlands) and Greer (Lenoir, North Carolina, US). The allergens come ready diluted in vials, and are drawn up in quantities of 0.05 ml doses in insulin syringes for injection (Figures 4 and 5). The patient is sedated with meditomidine (acetyl promazine inhibits histamine release so should not be used). An area is shaved on the animal's side, preferably lesion free, using fine bladed clippers to avoid skin damage (Figure 6). A marker is used to mark out rows for injection. Histamine and saline are injected as positive and negative controls respectively. Subsequently the allergens are injected opposite the marked areas (Figures 7 and 8). Care is taken to inject intradermally and not too deep resulting in a subcutaneous injection and no response. Responses are read after 30 minutes, and positives noted (wheals greater than half the mean of positive and negative controls). Delayed responses are possible, so the site should be checked at 12 and 24 hours post injection. It is important that the patient should be adequately weaned off steroids prior to testing (4 weeks following oral medication and several months following depo steroids) and also antihistamines (2 to 4 weeks).

Histopathology

Skin biopsies are useful to identify the specific pathology of certain skin problems (e.g. neoplasia). It is important to state that a conclusive diagnosis is not always possible, but can be used to rule in or out certain skin problems. Lesional skin is injected with local anaesthetic (not containing adrenaline) and samples are taken with a punch biopsy or a scalpel. The resultant biopsy sample should be handled carefully (avoid crushing) and put in formalin for submission to a dermatopathologist.

Diagnosis and treatment of ectoparasites

Fleas

A thorough work up should enable a diagnosis to be reached. Fleas and flea allergic dermatitis are very common presentations (Scheidt, 1988). Lesions usually involve the dorsum, but in long-standing cases will spread over the body. Exploration of the coat for fleas with a flea comb is usually most rewarding on the dorsum and the groin region. Lesions are often papular with hair loss. Pruritus is moderate to severe, and secondary pyoderma can be seen. Effective flea control of the animal and environment should resolve symptoms.

Mites

Sarcoptes scabiei causes a very pruritic dermatosis. People can be affected with transient papular lesions. It is highly contagious and often recent contact with an affected dog in kennels or with infected foxes is noted. Other dogs in the household may be affected, and the mite can be transmitted to cats. Lesions affect the pinna especially the edges, elbows and extremities (Malik et al, 2006). Papules and crusts are present, but chronically affected cases can become generalized, with lichenification, alopecia and hyperpigmentation, an ‘itch/scratch reaction’ can frequently be elicted by rubbing the pinnal edge. Mites can be hard to find but best results are obtained by multiple skin scrapings, especially from lesions on the pinna and elbows (Figures 9 and 10). In the early stages of sarcoptic mange, mites are frequently difficult to find, and the use of a serological test for antibodies against sarcoptes may be helpful. Topical spot on avermectin presentations or amitraz washes given for long enough (4 weeks minimum) are effective (Curtis, 2004). All in contacts must be treated, as well as bedding.

Cheyletiellosis is usually seen in young dogs, but not exclusively. A history of a visit to kennels or grooming parlour is often the case. Owners may have concurrent lesions and other animals in the house will be affected. Affected dogs will often have scaling and varying degrees of pruritus with papules especially along the dorsum. Acetate tape preparations, skin scrapings and coat brushings should yield the mites and eggs attached to hairs. Treatment with an effective miticide for 4 weeks, including all contacts, should resolve the problem.

Neotrombiculosis caused by harvest mites is a seasonal pruritic skin disease, occurring in late summer to autumn. Larval mites are seen as bright orange dots (confirmed by sampling and examination under a microscope) (European Scientific Counsel Companion Animal Parasites, 2010) (Figure 11) between the toes, on feet, legs and pinnae (especially in Henry's pocket). Insecticidal shampoos and topicals are effective but recurrence is frequent.

Certain strains of Demodex Spp. in dogs are pruritic (Figure 12). Diagnosis is by deep skin scrapings and treatment is with amitraz topically until sequential skin scrapings are negative (Scott, 2001).

Lice

Pediculosis (lice) is most often seen with poor coat condition and lice are usually visible to the naked eye in the coat. An effective insecticide should be used for 4 weeks.

Diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis is a very common cause of pruritus in the dog. There is a defect in the skin's barrier function allowing access by allergens, such as pollens and house dust mites, to induce an allergic response in sensitized individuals. This defective barrier function allows transepidermal water loss and colonization of the skin by microbes, all contributing to the pruritus. Onset of clinical signs is usually between 6 months and 3 years. Initially there may be no skin changes, but self trauma will ultimately lead to skin lesions developing. As outlined earlier, certain breeds are more susceptible, but most breeds can be affected. Seasonality is often a feature, but ultimately most cases will become perennial later. A very important concept in atopic cases is the influence of flare factors. Ectoparasitism, infections, other hypersensitivities and environmental factors can exacerbate the pruritus. Staphylococcus and malassezia are important flare factors.

Lesion distribution is very useful in diagnosis and usually involves feet, face, ears, ventral abdomen and axillae. Chronic cases develop lesions of excoriation, alopecia, saliva stains of the coat, lichenification, hyperpigmentation and secondary pyoderma. Otitis externa and periocular dermatitis are not uncommon signs. Initially ear lesions will be confined to the inner concavity of the pinna (Figure 13) and the upper ear canal, with little or no involvement of the deeper canal. This can be a very useful indicator of the disease. In some cases recurrent pyoderma can be the only sign (Favrot et al, 2010).

A diagnosis of atopy should be based on suggestive historical signs, lesion distribution and finally supported by positive responses in intradermal skin tests or serology. It is important to rule out other pruritic dermatoses using the diagnostic aids discussed earlier. Willemse described criteria to diagnose atopy (Table 2); skin testing and serology were regarded as minor criteria in reaching a diagnosis (Willemse, 1986). At least three major criteria were required and then at least three minor criteria.

| Major criteria | Minor criteria |

|---|---|

| Pruritus | Onset of signs before 3 years of age |

| Facial and/or digital involvement | Facial erythema and cheilitis |

| Lichenification of flexor surface or tarsus or extensor surface of carpus | Conjunctivitis |

| Chronic/chronically relapsing dermatitis | Superficial staphylococcal pyoderma |

| Individual or family history of atopy | Hyperhidrosis |

| Breed predilection | Positive intradermal skin test |

| Positive serology |

It is important to explain to an owner that atopy is a life-long disease and control is the objective not cure. Failure to do this is the single most common cause of client dissatisfaction (personal observation). The best results are achieved by a combination of therapies rather than a single therapy. Therapy should include anti-inflammatory medications, addressing the defective barrier function, identifying flare factors and allergen avoidance/allergen immunotherapy. The aim is to reduce the animal's pruritic threshold below the level that induces itch. Initial control of ectoparasites (especially fleas), staphylococcal and malassezia infections prior to specific therapy is important. Until this is done, the true pruritus of the hypersensitivity cannot be seen. Explore other hypersensitivities, such as food for their role (see below).

Addressing the defective barrier function is important but often overlooked. Dietary supplementation with essential fatty acids, either in commercial diets or as an additive is helpful. Topical therapy with emollient shampoos like Allermyl is very useful. Antihistamines, like cetrizine, clemastil, chlorpheniramine and hydroxizine, can help to control mild uncomplicated cases (Scott and Miller, 1999). A Chinese herbal product, Phytopica, can help (Schmidt et al, 2010). Steroids are best used sparingly, because of systemic side effects, but are very effective, especially in seasonal cases. A topical steroid, Cortavance (Virbac) (hydrocortisone aceponate spray), has been very effective. Atopica, a cyclosporine product, has been very useful. Vomiting for the initial 4 days of dosing can be overcome using the antiemetic, Cerenia (maropitant). There are some rare side effects, but these usually regress on stopping the medication. Allergen specific immunotherapy is directed at the cause and is successful in about 60% of cases (Griffin and Hillier, 2001).

Food hypersensitivities are not uncommon. Clinical signs are similar to atopy, but can occur at less than 6 months of age. Lesions involving the pinnae and perianal region should arouse suspicion. Diagnosis is by feeding, preferably, a home cooked novel diet (e.g. a protein and carbohydrate source not fed before) for 8 to 12 weeks, and then re-challenge with original diet. Commercial hydrolyzed diets are available but are not as reliable for diagnosis. Serology is not reliable for diagnosis and treatment is by avoidance.

Conclusion

In conclusion, successful management of pruritic dogs requires careful history taking and a thorough physical examination. Finally by using the diagnostic aids indicated, a definitive diagnosis should be reached and a successful outcome achieved.