Skin disease is a commonly encountered condition in clinical practice, accounting for an estimated 21% of the caseload for veterinary surgeons in general small animal practice (Hill, 2006). For many pet owners, skin and coat condition is an indicator of their pet's general wellbeing and can often prompt concern if it declines. The most common causes of skin disease tend to be allergies from parasites, particularly fleas, environmental allergies and adverse food reactions (AFRs). AFRs or food allergies generally account for a much smaller proportion of cases of dermatological disease than flea bite hypersensitivity or atopic dermatitis. In fact, food allergies only account for around 1% of dermatological cases (Verlinden et al, 2006), although the perception from many pet owners is that they are much more common.

When considering the role of nutrition in a patient with skin disease, there are two main focus areas. The first is the role of diet (particularly limited antigen or hydrolysed diets) in skin sensitivities suspected to be a result of an adverse food reaction. Second, nutritional modification can play a key role in the support of any patient with atopic dermatitis, skin sensitivities or a poor skin or coat quality, particularly as part of a multimodal management approach. In addition to this, even in dogs considered to have ‘healthy’ skin, as well as for owners who exhibit their dogs professionally, there may be a desire to seek a superior skin and coat condition. This article explores the role of specific dietary nutrients in skin and coat health, as well as their role in some skin conditions. The role of dietary management in adverse food reactions will be the subject of a follow-up article.

A full dietary history

Veterinary nurses can play a crucial role in assisting with a full dermatological history to aid the diagnosis of any skin disease. As part of this, obtaining a full dietary history from owners is key. This may help to identify any potential nutrient deficiencies or excesses, as well as rule in or out a potential AFR. Dietary history forms, such as that shown in Figure 1, can be an invaluable tool to obtain this information and careful questioning is often needed to maximise the amount of information that can be ascertained.

Protein

The skin is the largest organ in the body, and has a high turnover rate. The epidermis is renewed approximately every 3 weeks, and protein has a crucial role to play in this. Each hair is composed of 95% protein; therefore, protein level and quality within the diet is a key consideration when looking to optimise skin and coat quality (Figure 2). The minimum recommended dietary protein intake for healthy dogs is 18% on a dry-matter basis (FE-DIAF, 2021). However, to optimise skin and coat recovery in a dog with skin disease, a dietary protein content of 25–30% is desirable (Roudebush and Schoenherr, 2010). The quality of protein and bioavailability may also be important considerations.

In addition, specific amino acids may play particularly important roles in healthy hair and skin. For example, increased levels of proline, glycine, lysine and arginine — key building blocks for collagen, which is a principal component of the dermis — are found in some diets, which are specifically designed to maximise skin support. Arginine can also play an important role in skin construction and immune function. Tyrosine is a key amino acid serving as a precursor to melanin, and a deficiency in this (which may be a particular risk with a homemade diet) can cause a reddening of black hair. A deficiency of dietary protein compared with a pet's individual requirements can cause thin, dull brittle hair.

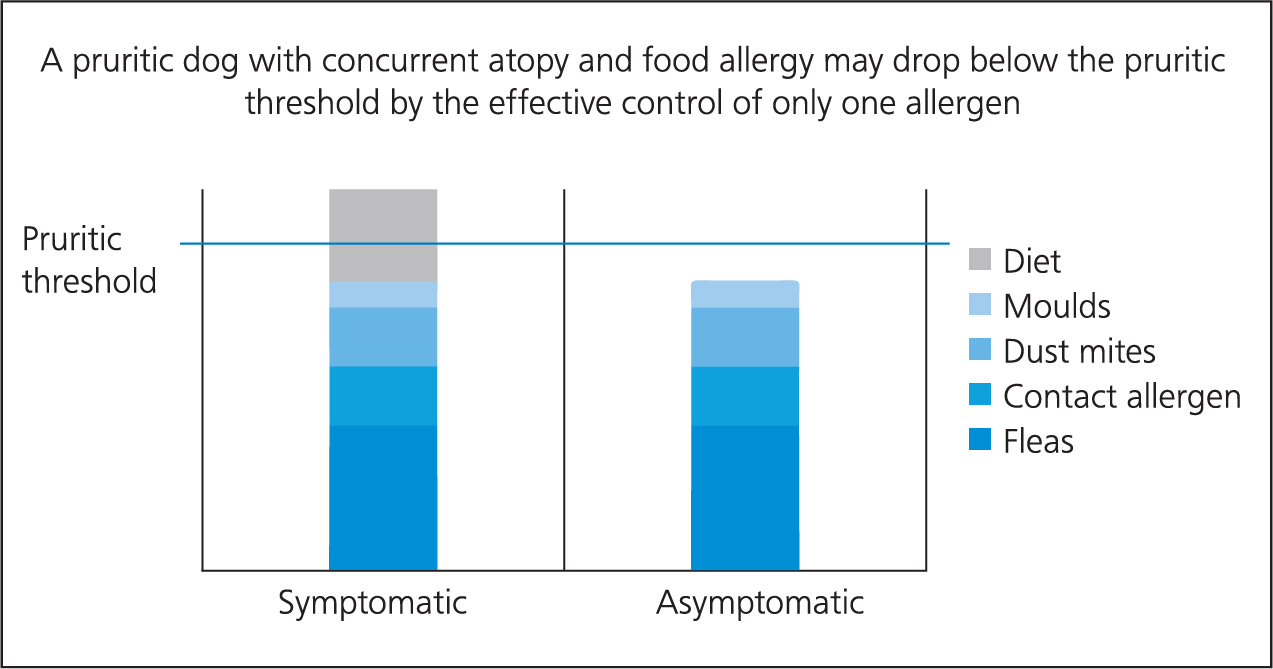

Concurrent gastrointestinal and dermatological signs in an individual increase the likelihood of an AFR rather than atopy (Picco et al, 2008). One study suggested that among dogs diagnosed with atopy, nearly 17% also had a concurrent food allergy or intolerance (Proverbio et al, 2010). In such cases, it may be that controlling one allergy (e.g. the food allergy) may be enough to prevent clinical signs (Figure 3). In any pet where there are concerns of a potential AFR, the type and number of proteins within a diet may be a consideration. In such cases, there are two key dietary choices: either a hydrolysed diet (where all proteins have been enzymatically cleaved, reducing their size to below the molecular weight needed to stimulate an immune reaction), or a diet containing a reduced number of protein sources, preferably novel proteins which the pet has not been exposed to. Where a limited or novel protein diet is selected, the most common proteins responsible for food allergies, such as chicken, beef and dairy in dogs (Mueller et al, 2016), should be avoided. Many of the commercially available diets designed to support pets with dermatoses will have these features. Further management of AFRs will be discussed in part 2.

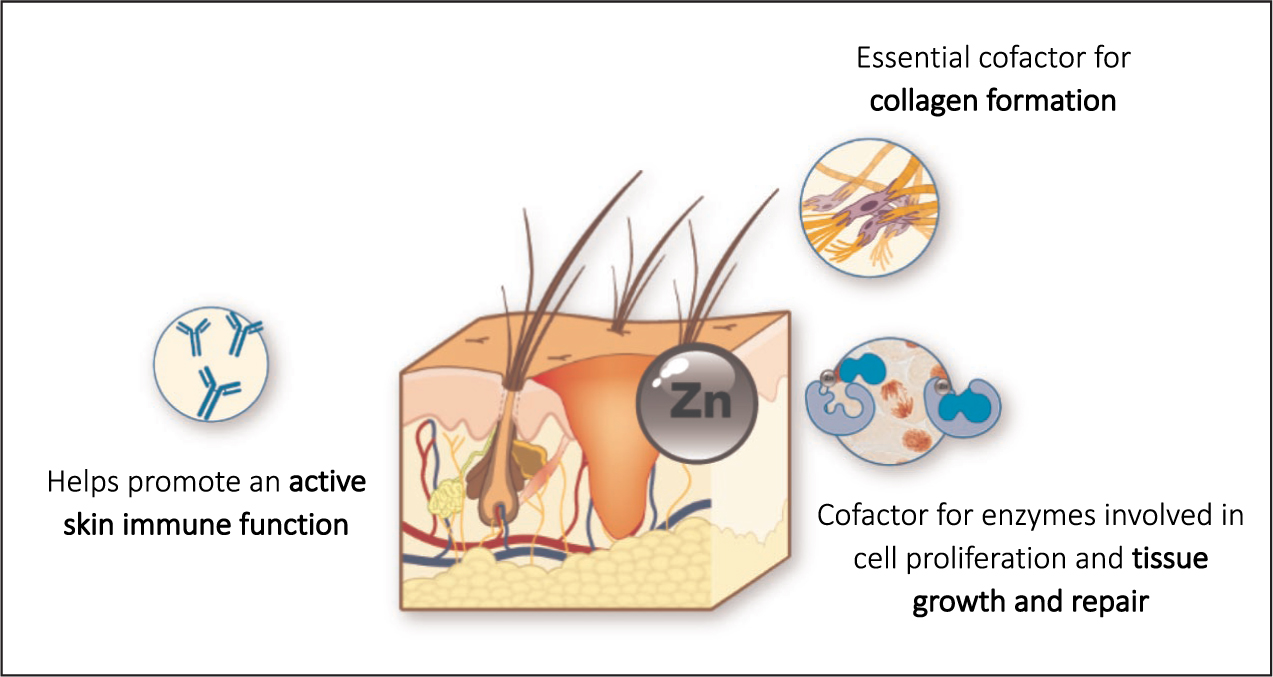

Zinc

Zinc is a co-factor for many enzymes, including some that play important roles in the skin (Figure 4). For example, zinc-dependent metalloproteinases are involved in keratinocyte migration and wound healing. Zinc is supplied in the diet and is not stored in appreciable levels in the body. Two syndromes of zinc-responsive dermatoses exist, both presenting with typical histopathological findings including parakeratosis and dyskeratosis. Clinical signs include a symmetrical distribution of skin lesions including alopecia, erythema, scaling, crusting, and lichenification. Syndrome I in Arctic breeds, such as Huskies and Malamutes, is associated with zinc malabsorption in the intestinal tract, because of a genetic defect. Syndrome II occurs in rapidly growing large and giant breed puppies, either fed a zinc-deficient diet or one containing high levels of ingredients that impair zinc absorption. In particular, zinc deficiencies are one of the most common nutrient deficiencies in home-prepared dog diets (University of California Davis School of Veterinary Medicine, 2013), and may also occur in any lower quality diet high in cereal, and particularly phytates, since these inhibit zinc absorption. With improvements in the quality of commercial diets, however, this is not commonly seen nowadays. A high dietary calcium content — whether within the main meal or as a result of additional calcium supplementation — is also known to reduce zinc absorption. In any dog where zinc supplementation is required, high dietary cereal or calcium content should be avoided. While many diets designed to provide dermatological support have increased levels of zinc, they remain lower than the therapeutic levels needed for most zinc-responsive dermatoses. Additional daily oral zinc supplementation is therefore often also indicated, particularly with the familial form. After starting an appropriate complete and balanced diet, ideally one designed to support the skin, and with appropriate zinc supplementation, clinical improvements should begin to be seen within 4–6 weeks. If improvements in skin lesions are not seen, the form or dose of zinc supplementation may need to be adjusted.

Vitamins

Vitamin A has an important role to play in epidermal differentiation and normal sebum production. Although uncommon, deficiencies may result in altered skin barrier function and skin scaling, poor hair coat, and alopecia.

Vitamin E is the primary antioxidant in the cell membrane, and can protect fatty acids in the skin from oxidative damage. One study found atopic dogs to have a lower plasma vitamin E concentration compared with control dogs, and vitamin E supplementation for 8 weeks improved the subjective pruritus score (Plevnik Kapun et al, 2014). However, it was unknown if this was related to an improvement in skin barrier function score. In another study, supplementation with vitamin D was shown to reduce the Canine Atopic and Dermatitis Extent and Severity Index (CADESI) scores in atopic dogs, potentially because of its immunomodulatory effects (Klinger et al, 2018). Thus, levels of these vitamins in the diet may be an important consideration in dogs with skin conditions.

Essential fatty acids

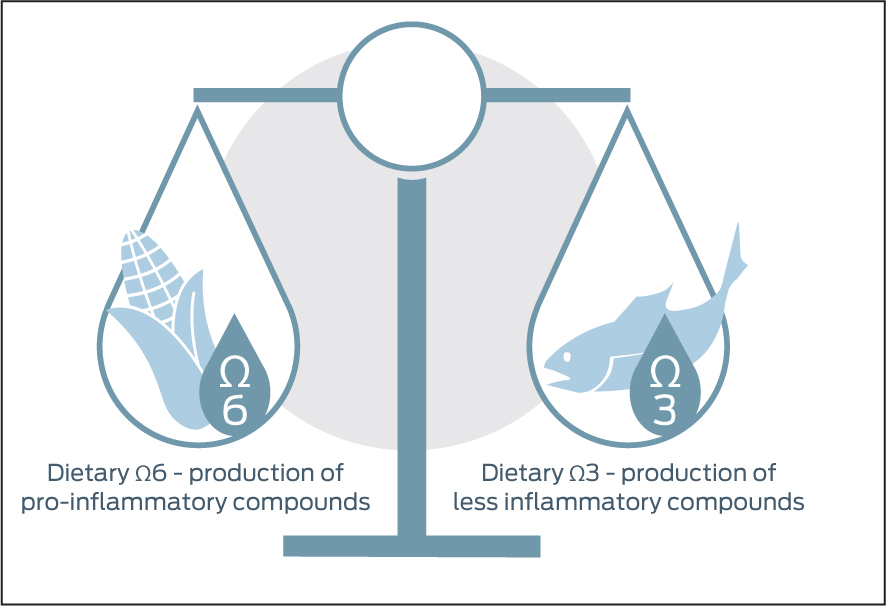

A healthy skin barrier is vital to help minimise water loss and protect the body from environmental insults. Omega fatty acids have a particularly important role to play in this (Figure 5). Dogs with atopic dermatitis may have a defective barrier, including higher transepidermal water loss, compared with healthy dogs (Cornegliani et al, 2011). Nutritional modification, particularly increased levels of dietary omega 6 fatty acids, may therefore play a role in supporting skin barrier function. Linoleic acid is an omega 6 essential fatty acid (EFA) that is incorporated in the ceramides of the skin (Reiter et al, 2009); deficiency results in dry, coarse skin. Increased levels of linoleic and alpha-linolenic acid help to retain skin moisture and can restore coat lustre in pets with dry skin or dull coats (Case et al, 2010). In combination with zinc, linoleic acid has also been shown to make significant and substantial enhancements of the skin and coat condition in healthy dogs, as well as decrease transepithelial water loss (Marsh et al, 2000). In dogs with zinc-responsive dermatoses, it has been suggested that if supplementation with zinc alone is ineffective, addition of linoleic acid may lead to greater improvements in skin and coat quality (Purina Institute, 2022a). Vegetable oil supplements, particularly corn oil, can be helpful to improve hair coat quality, although more studies are needed to determine the most effective dose and composition of this supplementation (Popa et al, 2011). Alternatively, commercially available skin-supportive diets invariably contain increased levels of omega 6 fatty acids.

Omega 3 fatty acids, e.g. eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), result in cytokine production with less inflammatory characteristics than omega-6 EFAs and may decrease pruritus in dogs (Logas and Kunkle, 1994). In dogs with atopy, clinical scores were significantly improved when supplemented with EPA and DHA (Mueller et al, 2004). Where owners wish to supplement the diet with omega 3 fatty acids, it is particularly important to consider the fatty acid profile of the supplement. For example, α linoleic acid — from linseed oil — is an essential fatty acid but conversion to EPA and DHA in the body is poor: dogs are generally able to convert <10% to EPA and <5% to DHA. Thus, when selecting a fatty acid supplement, fish oils (a particularly rich source of EPA and DHA), commercially available veterinary supplements with sufficient evidence for their use, or a dermatosis diet with increased omega 3 fatty acid content, are better recommendations. Selecting an appropriate diet rather than a nutritional supplement may be preferable for several reasons. The amount of a supplement given by an owner may vary from recommended levels. Fatty acid supplements can be highly calorific, leading to weight gain if a pet is regularly ingesting excess calories, or nutritional imbalances if the main meal has to be reduced significantly to avoid weight gain. Furthermore, supplements rely on an owner remembering to administer this daily, and may be of variable palatability.

The optimal omega 6:omega 3 fatty acid ratio remains unknown. In one study, no correlation was identified between omega 6:3 ratio and clinical scores, and this did not appear to be a key factor in determining the clinical response (Mueller et al, 2004). Although various ratios are quoted, more studies are required to determine an optimum ratio — if any such ratio exists — in dogs with skin conditions.

Microbiome and probiotics

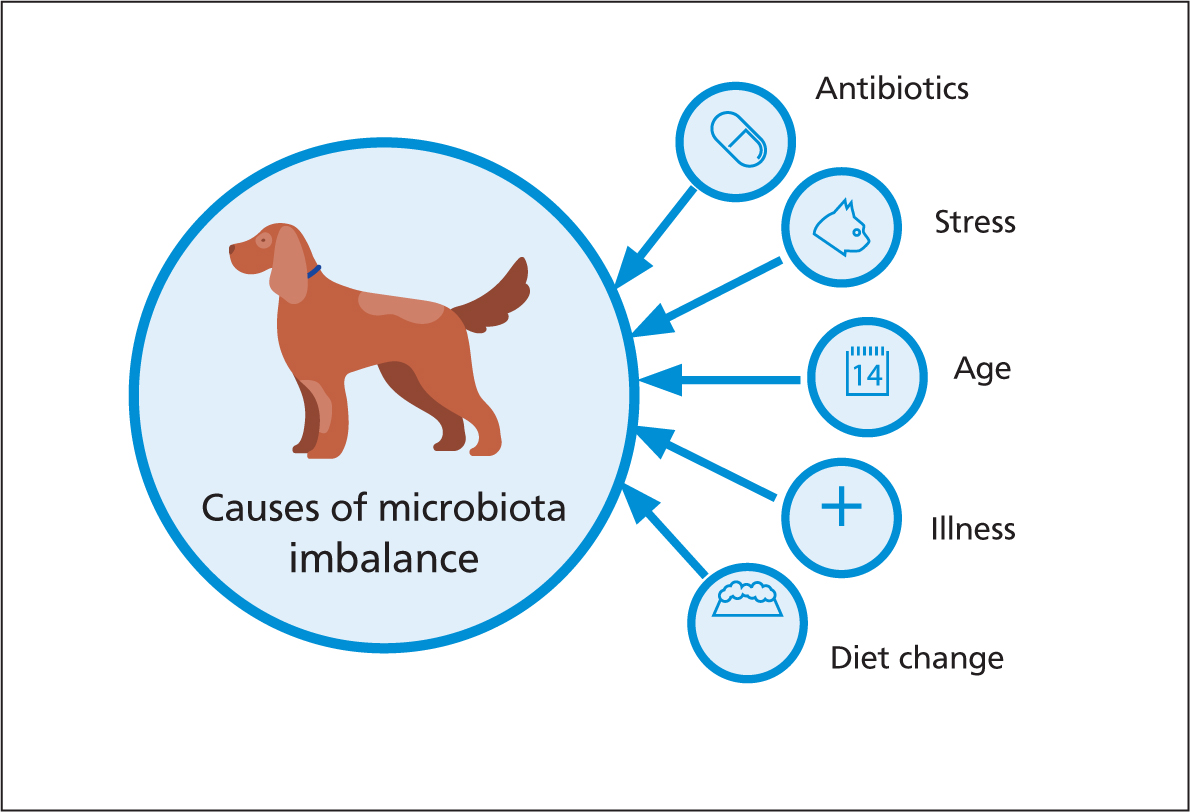

Dogs' skin is inhabited by rich and diverse microbial communities (Hoffmann et al, 2014), and dogs with allergic skin disease have been found to have lower species richness compared with healthy dogs. Manipulation of the skin microbiome could potentially play a future role in management of atopic dermatitis. The intestinal microbiota may also have a role in atopic dermatitis, and there are many reasons this can be disrupted (Figure 6). An impairment of the intestinal mucosal barrier, and intestinal microbiota differences, may be involved in the pathogenesis of human atopic disease — and there appear to be parallels between atopic humans and atopic dogs. It has therefore been suggested that manipulation of the canine intestinal microbiota could be considered as a novel way to help manage atopy (Craig, 2016).

Probiotic products differ widely in composition and number of microbes. However, several products appear to have an immunomodulatory effect and could play a role in the management of canine atopic dermatitis.

In one double-blinded, placebo-controlled study in dogs diagnosed with canine atopic dermatitis, oral administration of a heat-killed faecalis FK-23 preparation resulted in significant improvements in the canine atopic dermatitis extent and severity index (Osumi et al, 2019). Administration of the probiotic strain, Lactobacillus sakei probio-65, for 2 months significantly reduced the disease severity index in dogs with atopy (Kim et al, 2015).

Another study showed that the probiotic, K71, used as a complementary therapy, provided a corticosteroid- and ciclosporine-sparing effect (Ohshima-Terada et al, 2015). There is currently insufficient evidence to draw any clear conclusions, but further studies are warranted in this area to allow future recommendations.

Probiotics could become a useful adjunct treatment in some dogs with atopy. It is important to emphasise that individual properties and actions of probiotics are species- and strain-specific; thus, findings with one probiotic cannot be extrapolated to other probiotic supplements that may already be commercially available.

Conclusion

Nutrition has a fundamental role to play in supporting skin health. Nutritional deficiencies, imbalances or AFRs may contribute to a poorer skin and coat quality. However, specific nutrients or commercially available dermatological support diets may play a key role as part of a multimodal strategy to support an individual with dermatoses or a dermatitis. Obtaining a full dietary history can be very helpful when determining whether potential nutritional deficiencies or excesses could be contributing to an individual's clinical presentation. Selection of a diet with an appropriate nutritional profile for an individual patient (for example, ensuring a dermatological support diet, rather than a hypoallergenic hydrolysed diet, is chosen for the majority of atopy cases) is important. A number of commercially available dermatoses diets with strong evidence for their efficacy now exist, and they can form a key part of successful support of patients with a variety of skin conditions alongside pharmacological agents and topical products.

KEY POINTS

- The most common causes of skin disease are allergies to parasites, particularly fleas, or the environment (atopic dermatitis). Adverse food reactions (AFRs) account for a small proportion. In all of these, nutrition can play a key role in multimodal management to support the skin barrier.

- Poor quality or imbalanced nutrition (for example, as a result of a homemade diet) can cause a poor skin and coat quality.

- Protein plays a crucial role in skin health; 95% of each hair in the dog's coat is composed of protein and adequate levels and protein quality are crucial to support skin condition.

- Selection of a diet excluding the most common protein sources thought to underlie AFRs (chicken, beef and dairy) is sensible in many patients with skin disease, particularly as some dogs with atopic dermatitis may also have an element of AFR complicating their clinical signs.

- Zinc is a key micronutrient important in skin health. In cases of zinc-responsive dermatoses, additional zinc supplementation alongside a dermatological diet is usually required to optimise improvement and recovery.

- Omega fatty acids have a crucial role in skin health. Increased omega 3 fatty acid levels, particularly eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), can help to promote natural anti-inflammatory responses. Increased omega 6 fatty acid levels can help retain moisture and reduce transepithelial water loss.

- Manipulation of the intestinal microbiome with probiotics, and/or the skin microbiome, may form novel strategies in the future to help manage atopy.