Preparing for, and monitoring of general anaesthesia (GA) in cats and dogs is a large part of a registered veterinary nurse's (RVN's) responsibility in practice. Dental anaesthesia may be for a 10 minute scale and polish on a fit healthy Labrador or extensive extractions on a 16-year-old cat with several co-morbidities. Therefore the anaesthesia and analgesia requirements of the dental patient in the perioperative period should be considered and prepared for on an individual basis, although the basic care requirements remain the same. Due to the nature of dental disease progressing with age, and the increased life expectancy of animals, many of the patients presenting for dental work can be classified as geriatric, in the last 25% of their expected life span (Bradbrook, 2016). As well as the considerations that go with any other dental anaesthesia the specific requirements of the geriatric patient must now be considered. The ageing process affects many body systems and alterations in anatomy and physiology of the geriatric patient may affect pharmacology of drugs administered in anaesthesia (Bradbrook 2016). Thorough pre-op assessment, careful choices, vigilant monitoring and attentive supportive care will improve the probability of a successful outcome for the elderly patient (Hughes, 2008).

Considerations for patient preparation

Pre anaesthetic fasting

All animals undergoing general anaesthesia require a degree of fasting , dependent on age, to decrease the amount of food and fluid in their stomach; thereby decreasing the risk of vomiting, regurgitation and aspiration. In adult healthy dogs there is considerable variation in fasting guidelines, both in the literature and in practice (from 6–12 hours for food and 0–2 hours for water (Savvas et al 2009)). Animals being fed at their regular meal time in the early evening could result in a fasting time of approaching 20 hours when considering ‘dirty’ dental procedures may be performed at the end of the surgical list. Prolonged fasting in animals has been associated with increased incidence of reflux and gastric acidity and this may increase damage to the oesophageal mucosa (Galatos and Raptopoulos, 1995). In a study of 15 dogs, Savvas et al (2009) showed canned food at a half daily amount fed 3 hours before anaesthesia did not significantly increase the gastric content volume while acidity was reduced compared with six other feeding protocols. The length of time to fast a patient is still debated and many practices differ, patient age and co-morbidities will also needs considering. A moderated fasting period of 6 to 8 hours in adult healthy patients prior to premedication may mean a small tinned meal given by the client last thing at night or early morning depending on the planned procedure time.

Pre anaesthetic blood screens

Provided no abnormalities are found on the clinical examination and patient history a pre-anaesthetic blood test may be considered unnecessary. A study of 1537 dogs of all ages showed little evidence that pre-anaesthetic blood work was likely to give additional important information if no potential problems were identified in the history and physical examination (Alef et al, 2008). However veterinary discretion remains and the age of the patient will have an influence on the decision; pre-anaesthetic blood screening in dogs over 7 to 8 years of age is recommended as 30–50% have sub clinical diseases (Rigotti et al, 2016). The same may apply for cats over 10 years of age however there is currently no literature published on pre-anaesthetic blood work in the species (Bradbrook, 2016).

Premedication

Drug selection should be made on a case by case basis, considering pre-anaesthetic clinical findings, American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) status (Table 1), patient signalment, temperament and the extent of anticipated extractions (pain). In a number of cases, especially some geriatrics, paediatrics and compromised patients, an opioid may be all that is required. The choice of opioid will depend on the degree of analgesia required as well as speed of onset and duration of action (Murrell, 2016). For moderate to severe pain a full mu agonist such as methadone is recommended, whereas where only mild pain is anticipated a partial mu agonist such as buprenorphine may be suitable (Murrell, 2016). Where additional sedation is required to facilitate intravenous catheter placement and a smooth stress free induction, a sedative such as acepromazine or an alpha-2 adrenoceptor agonist may be added. Depending on the drug used and route administered sedation times will vary. It is important to wait sufficient time for peak effect even when administered intravenously (IV). Once premedication has taken place thought to maintaining body temperature should begin, see active warming preparation below.

| Status | Definition | Risk | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASA 1 | A normal healthy patient | Minimal risk | Ovariohysterectomy, castrate, orthopaedic patient |

| ASA 2 | A patient with mild systemic disease | Slight risk | Neonate or geriatric. Controlled diabetic |

| ASA 3 | A patient with obvious systemic disease | Moderate risk | Anaemia, low grade cardiac disease, dehydration, liver disease |

| ASA 4 | A patient with severe systemic disease that is a constant threat to life | High risk | Shock, uncontrolled diabetes, emaciation, high fever, uncompensated heart disease |

| ASA 5 | A patient not expected to survive without the operation | Extreme risk | Severe trauma, profound shock, advanced heart disease |

Preparation of equipment

Check lists

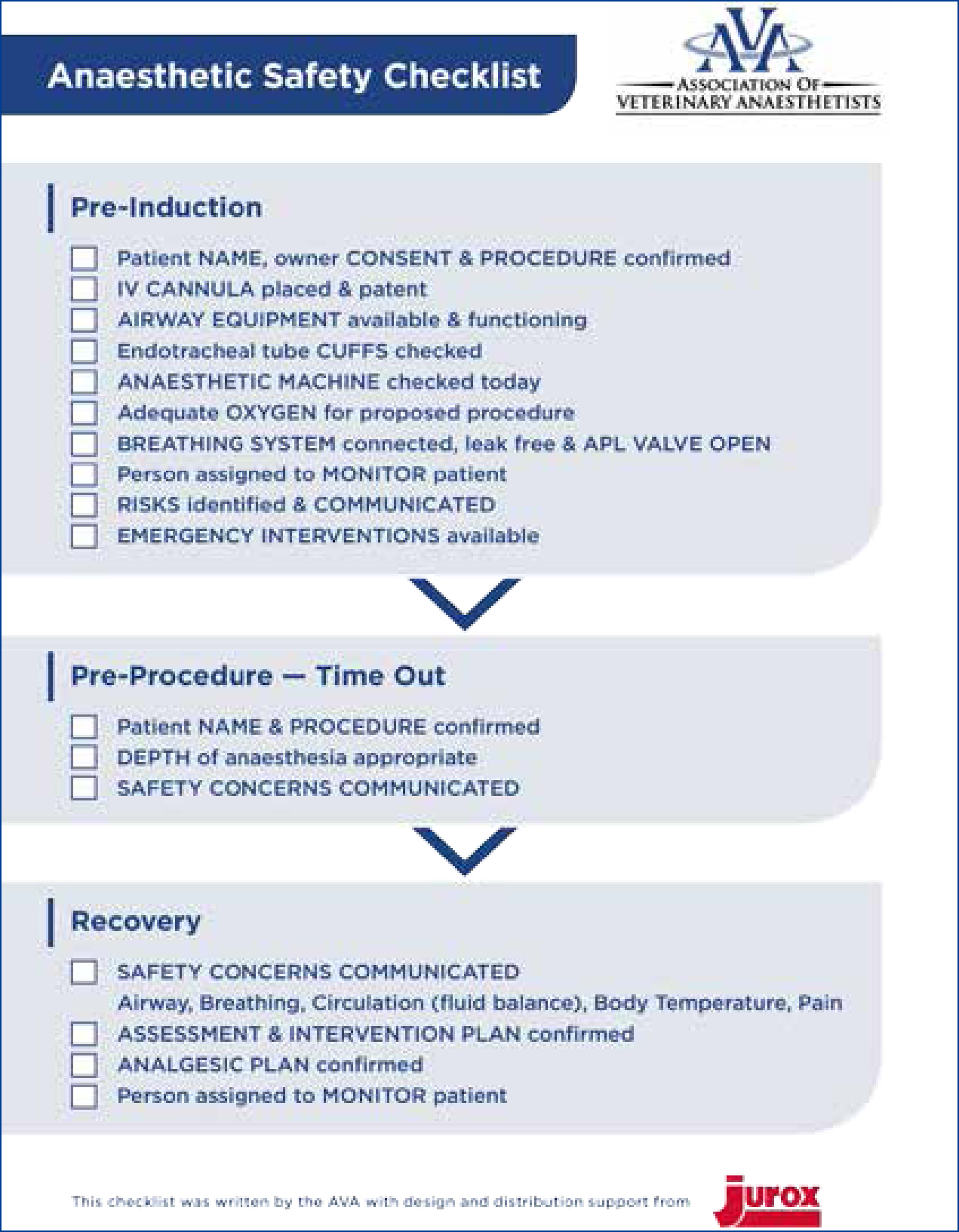

Using a check list to prepare for anaesthesia and surgery is important for ensuring that the veterinary team are prepared for the surgery to take place and that all safety measures required are applied and documented. The purpose of a checklist is to detect a potential error before it leads to harm; users are given the opportunity to pause and consider important actions before moving on. The Association of Veterinary Anaesthetists (AVA) in 2014 developed an anaesthetic safety checklist for veterinary use (Figure 1) which can be found on their website for download, www.ava.eu.com/resources/checklists/. It covers pre-anaesthesia considerations, the anaesthetic machine check, drugs, equipment and recovery ensuring communication between team members at every stage.

Airway considerations

An endotracheal tube (ETT) is mandatory for dentistry; a tube with a cuff is preferable in most situations, other than paediatric patients due to the concern of tracheal damage (Palmer, 2010), as it will provide additional airway protection. The tube should be cut to the correct length to facilitate securing in place, reduction of dead space and prevention of bronchial intubation and one lung ventilation (Figure 2). The cuff should be checked prior to use, for leaks, damage and contamination (Figure 3); a deflating cuff during surgery increases risk of aspiration pneumonia and serious postoperative complications. ETT cuff pressures in excess of tracheal mucosal pressure can cause a decrease in tracheal mucosal blood flow and consequently cause tracheal epithelial damage (Briganti et al, 2012), resulting in necrosis or rupture (Hughes, 2016). Concerns have been raised about the use of cuffed tubes in cats for these reasons, however the cuffs on modern disposable PVC tubes are made from very thin material and are available as high volume with low pressure spread over a larger area, (see Figure 3), reducing the risk of damage to the tracheal mucosa (Hughes, 2016).

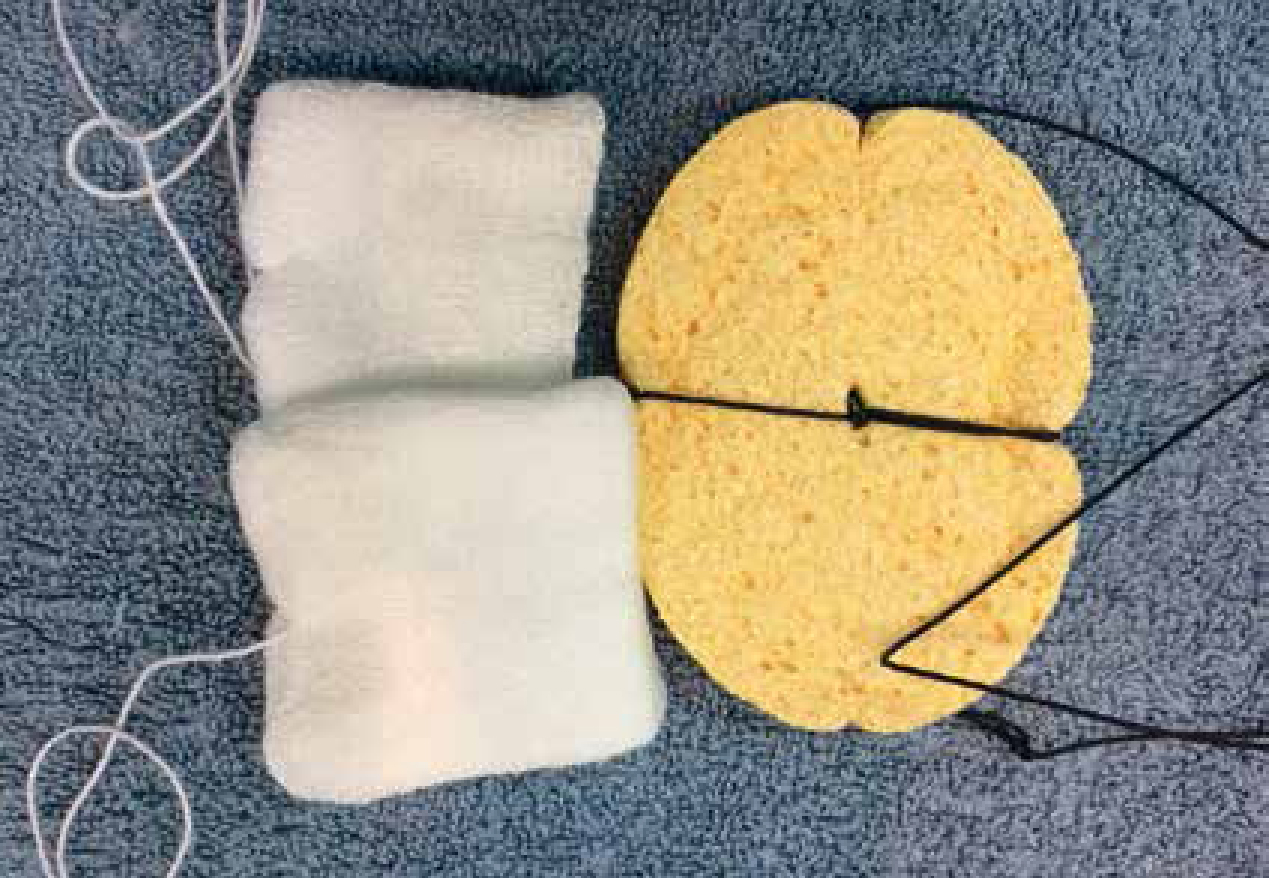

When using palpation of the pilot balloon and minimal occlusive volume for cuff inflation operators in a study by White et al (2017) rarely achieved optimal intracuff pressure, experience had no effect on this skill. Therefore use of a cuff manometer is recommended with guidelines for optimal pressure varying between 20–30 cmH2O. Syringes are now available that allow measuring of cuff pressure when inflating a cuff. When changing any patient's position, safely disconnect the ETT from the breathing system to ensure the ETT does not rotate within the trachea, a risk factor for tracheal rupture. In addition, securing the tube in place to prevent kinking or extubation is important when considering the amount of movement of the head during a dental procedure. With half of the tie placed in front and half behind the ETT connector (over a wing) the tie and tube remain together in place. ETT ties for dentals that are visible, do not bind to hair and do not soak up blood or saliva are available to buy, alternatively old giving set lines can make effective tube ties for oral procedures. A throat pack (Figure 4) is also vital to guard against aspiration; there are several types and sizes available. Mark on the general anaesthetic (GA) sheet when placed to prompt removal at the end of the procedure; tying the throat pack to the ETT so it will be removed with the tube will ensure that it is not forgotten.

A laryngoscope with suitable sized blade for the patient should always be available and checked pre induction for bulb or battery failure. The routine use of a laryngoscope will provide superior visualisation to the oral cavity and larynx, assisting with the placement of a suitable sized ETT, as well as ensuring competency in its use in an emergency.

Mouth gags

The use of spring loaded mouth gags is not recommended for cats as they have been identified as a potential risk factor for cerebral ischaemia and blindness in the species, thought to be due to maxillary artery compromise (Stiles et al, 2012). Further research evaluated the implications of wide mouth opening on the blood flow in the maxillary artery, — the results were consistent with circulatory compromise in some cats, while no changes were observed with smaller gags (Martin-Flores et al, 2014). Therefore care should be taken if and when wide mouth opening is needed in cats. A needle cap cut to 20–30 mm and used as a gag (Figure 5) enables adequate mouth opening for dental procedures without causing the lip and cheek to become tight, allowing access to the teeth (Reiter, 2014).

Active warming preparation

Perioperative hypothermia is a common complication of premedication and GA and depending on the degree it can have severe physiological consequences (Tunsmeyer et al, 2009). These include reduction of the minimum alveolar concentration (MAC) of volatile agents, reduction of cardiac output, decreased liver metabolism and renal excretion of drugs, impairment of blood coagulation and reduced immune system function (Posner, 2007). Therefore prevention and treatment of hypothermia during the anaesthetic period is essential. Dental patients can be some of the easiest to maintain body temperature in as the RVN has access to the whole body (Figure 6).

Thought should be given not only to the anaesthetic period but the pre and post period too as temperature regulation is disrupted by drug administration. For instance acepromazine (ACP) resets thermoregulatory mechanisms and causes peripheral vasodilation increasing the rate of heat loss (Murrell, 2016). After administration of any premedicant the patient will benefit from pre-emptive warming. Measures to support body temperature include blankets, thermostatically controlled heat pads, space blankets (foil), warm air blowers and incubators. A study by Tunsmeyer et al (2009) demonstrated an increase of body temperature over time in dogs weighing less than 10 kg undergoing head or extremity surgery when wrapped in a foil rescue sheet. These are an accessible and cost-effective method of maintaining patient temperature for use in practice and the sooner warming of the patient is started the easier it is to maintain normothermia during anaesthesia. Warming a cold patient can be challenging (Bradbrook, 2016).

Intravenous fluid therapy.

Intravenous fluid therapy (IVFT) of a replacement crystalloid during the anaesthetic period will maintain normal ongoing losses, ensure adequate circulating volume to support arterial blood pressure (ABP) and maintain catheter patency (Davis et al, 2013). IVFT should be prescribed on an individual basis by the VS and with close monitoring adjusted as required. Previously recommended maintenance fluid rates of 10 ml/kg have been adjusted and current recommendations are below this to avoid hypervolaemia, especially in cats. The American Animal Hospital Association 2013 fluid therapy guidelines recommendations are to start with 3 ml/kg/hour in cats and 5 ml/kg/hour in dogs and reduce by 25% every hour until maintenance rates are achieved (Davis et al, 2013).

Patient monitoring

Continuous monitoring of the patient during any anaesthetic procedure is important for patient safety. Monitoring ability will depend on the equipment available and a suitably trained member of staff should be dedicated to the monitoring of the patient from induction to recovery. Monitoring does not end with extubation, recovery is a critical part of anaesthesia and someone must be assigned to closely monitor the patient until awake, normothermic and comfortable. Ensure the mouth and pharynx are clean and no blood clots or debris remain, ensure dogs have a good swallow reflex and a slightly inflated ETT on removal can help clear any fluid or deposits from the trachea (Bednarski et al, 2011). Cats should be extubated with return of a pinna reflex and monitored closely in sternal recumbancy with their nose slightly lower to aid any draining.

As with all GAs the use of human senses and monitoring of the central nervous system should be utilised where possible in the dental patient. Arterial blood pressure can be monitored in most practices with a Doppler where oscillometric or invasive monitoring such as on a multiparameter monitor is not available (Figure 7). By placing the Doppler probe over a peripheral pulse and securely taping in place an audible continuous pulse can be heard throughout the procedure. Using an appropriately sized cuff and a sphygmomanometer, regular ABP readings can be taken and recorded (Figure 8.) A minimum mean ABP of 60 mmHg, Doppler minimum 80–90 mmHg systolic, is desirable during general anaesthesia to ensure adequate organ perfusion and autoregulation (Bradbrook, 2016). Potentially the most informative monitor, a capnograph provides information on end-tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2), correct ETT placement, respiratory rate and inspired CO2 levels. It can also provide useful information, particularly applicable when working on the head, including disconnection from the system and increased resistance of breathing (ETT obstruction). Other important information includes breathing system leaks and cardiopulmonary crisis. Pulse oximetry is a non-invasive technique displaying oxygen saturation (SpO2) of haemoglobin in arterial blood, pulse rate and rhythm. However, it has a number of limitations that must be understood if the information provided is not to be misleading. There are several areas on the patient that are non-pigmented and allow the light to pass through, that the clip can be placed, such as a toe, the prepuce or vulva when the tongue is inaccessible (Figure 9). The electrocardiogram (ECG) monitors heart rate and rhythm which is important during GA as many agents can predispose the patient to arrhythmias. Therefore understanding a normal complex and alerting the VS to any changes is necessary. An oesophageal stethoscope may not be suitable during some dental procedures and a standard one should be available. Throughout the anaesthetic period regular temperature monitoring and recording is essential to ensure the warming methods in place are effective and hyperthermia is not induced. As well as the usual drying effects of GA when performing dental surgery patients' eyes are especially vulnerable to debris from drills and scalers. Ensure plenty of eye lubrication is available and topped up as required. Full discussion of patient monitoring under GA is beyond the scope of this article and the above has aimed to cover the main considerations for dental anaesthesia. Table 2 considers common troubleshooting in anaesthetic monitoring.

| Parameter | Measured by. | Acceptable range | Common causes of readings out of normal range. | Considerations. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arterial blood pressure | Oscillometry |

Diastolic 55–110 mmHg |

Hypotension:

|

Check anaesthetic depth |

|

Hypertension:

|

Check anaesthetic depth |

|||

| End tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2) | Capnography | 35–45 mmHg |

Hypercapnia: Hypoventilation Increased cardiac output (temporary) |

Check anaesthetic depth |

|

Hypocapnia:

|

Check anaesthetic depth |

|||

| Saturation of haemoglobin with Oxygen | Pulse oximetry | Greater than 95% on room air |

Patient movement |

Check signal strength, probe position |

| Heart rate/rhythm | Electrocardiogram (ECG) | HR dependent on species, breed and any drugs administered |

Bradycardia: Deep anaesthesia |

Check depth of anaesthetic. |

|

Tachycardia: Light anaesthesia |

Check ECG for double counting |

|||

| Arrhythmias | Check for artefacts, electrode contact |

Intraoperative analgesia

Pain is best controlled using several analgesic agents each acting on a specific site along the pain pathway, this is known as multimodal analgesia (Gurney, 2012). Excellent pain management in all cases is essential to help ensure a smooth comfortable recovery and a willingness to eat post surgery. This can be achieved by combining non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), opioids and locoregional anaesthesia. In turn this helps provide a balanced anaesthesia protocol resulting in a ‘smoother’ anaesthetic event, reduction in the volatile agent required, and therefore reduced risks of cardiovascular side effects such as hypotension. The importance of this is even greater in elderly patients that are more susceptible to anaesthesia induced hypotension and insults of vital organs (Burns, 2015).

Local anaesthetic nerve blocks

With a growing emphasis on improving pain management for animals loco-regional anaesthesia has gained popularity in veterinary medicine (Campoy and Schroeder, 2013). Local anaesthetic agents prevent the transmission of nociceptive impulses to the central nervous system, reducing the requirement for additional intraoperative and postoperative systemic analgesia. Loco-regional anaesthetic techniques should be considered in all cases undergoing a surgical procedure. With the knowledge of the relevant anatomy and techniques to perform local blocks of the nerves in the oral cavity all that is required is some simple equipment, including needles, syringes and local anaesthetic agents (O'Dwyer and Crick, 2015). Figure 10 shows the maxillary nerve block providing analgesia in dental extractions of the upper jaw. There are now many good books and chapters with clear illustrations and instruction on how to perform the common dental blocks (Table 3).

| Nerve | Area desensitised | Indications |

|---|---|---|

| Maxillary* | Maxillary teeth, nasal planum, upper lip, palate | Maxillary tooth removal, maxillectomy, mass excision, palate surgery |

| Mandibular* (inferior alveolar) | Mandibular teeth rostral to block, mandible, skin over lower lip | Mandibular tooth removal, mandibulectomy |

| Mental nerve | Teeth rostral to the mental foramen | Rostral mandibular teeth removal, rostral lower lip surgery |

| Infraorbital nerve (rostral continuation of maxillary nerve) | Upper lip and nose. Number of teeth affected depends on volume injected and distance into infraorbital canal | Surgery of nose, upper lip |

Systemic analgesia

If during the procedure there is a significant increase in heart rate, ABP and/or respiratory rate in response to surgical stimulus additional intraoperative ‘rescue’ analgesia may be required. Options for this include a bolus of fentanyl or ketamine, and depending on the timing a repeat of the premedication opioid. NSAIDs are widely used in veterinary medicine to treat postoperative pain and where no contraindications exist should be administered perioperatively and the patient discharged with a course prescribed by the VS. Opinion varies on timing of administration during GA, reports of NSAID induced renal damage have been associated with high doses or other factors such as dehydration, poorly managed anaesthesia, shock or pre-existing renal disease (Gurney, 2012). Therefore, it would seem reasonable in patients with no contraindications, if ABP has remained within normal limits and IVFT provided, to administer a dose of NSAID before recovery.

Conclusion.

This article has demonstrated the range of considerations required when involved in the GA for a dental patient. Careful pre-anaesthetic examination and an individual anaesthetic plan for every patient will help to ensure a successful anaesthetic, minimising any risk. There is plenty of straightforward and inexpensive care that can be provided to these patients to ensure a comfortable stress-free procedure and to encourage a speedy recovery.